If you are new to the Band, this post is an

introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs

updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult

posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments

are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it

right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up

there.

This is the second part of the Leonardo post. It's not that we planned to spend so much time on him - he just turned out to be way more profound and important than we expected. And we expected him to be the father of High Renaissance art.

The portrait of Lisa Gherardini - a bankers wife of petty aristocratic extraction - went on to become the most famous picture of all time. We'll explain why.

For something so iconic there is some mystery around the Mona Lisa. For one thing, he never delivered it. It was still with him when he died a decade and a half later in France. And there may have been another version. These possibilities are interesting, but are secondary to what makes this so much more significant than we thought.

The idea was to look at the leading creators behind the High Renaissance, but Leonardo proved to be a bit more than expected. His extraordinary genius led us to consider the possibility that his historical significance was greater than thought. We posited the loosely defined category of epochal minds to try and deal with the most extreme cognitive outliers. Individuals of such mental gifts that they largely create the era that they are associated with then become synonymous with that era to the future.

That, or they're the answer to the question "how to seat over 800 IQ points in a golf cart?"

What then jumped out was how they're all different, but all exhibit the same meta-process – universal synthesis, creative churn, new directions. And they appear to flow from one to the other across time. Thomas spins the world Aristotle spawns. Our contention is that Leonardo can be found between the Thomistic world and the Newtonian one.

Here’s the template we distilled in the last post. These figures are "epochal" because they define their era in a composite way. Their achievements bring it about and their personas define it.

Here's the problem for this post. The idea itself isn't bad for general discussion. It may not be concretely provable, but it does fit our understanding of history. The existence of words like Thomistic and Newtonian indicate that people are used to using these figures as descriptors. Ditto Aristotelian. Leonardo – not so much. Mainly because he didn’t write the sorts of magisterial tomes the others did that echoed through the ages.

But there’s more to meaning than words.

This was the value in the epochal mind game. It gave us a loose way to

conceptualize the extremity of genius in history, And that showed us

where and how to look for Leonardo.

Our contention is that Leonardo represents the same synthesizing impulse, creative churn, and embodiment of the new era as the others. Only there’s no great work to read to read it in. You have to see it. It’s in his persona and especially in his painting and drawing. It is true that Leonardo changes art, and that does matter for our arts of the West series. But the profundity only starts there.

Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation, around 1472, oil on panel, Uffizi

One of his earliest paintings - this was done while he was still in Verrocchio's workshop and had really only started his career. The figure types are typical of the earlier Renaissance, but there are details that point to his innovative future.

To really get at what Leonardo’s painting meant to him, we have to see that he treated it like a goal and a tool at once. It’s a goal in that he was always experimenting and looking to refine it. His different inquiries into other areas of interest all feed into his painting and make it as radical as it was.

Leonardo, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist, about 1499-1500, charcoal with white chalk on paper, mounted on canvas, National Gallery

It's technically a cartoon but that doesn't seem to do justice to the artistry. His study of light and shadow went into how he models the figures, his anatomy into how they pose, and various technical refinements in his drawing and painting techniques.

This attention to his craft is what makes his painting seem like a goal in itself.

But his painting – and drawing – are the tools he uses to explore then express his understanding of an ontologically layered and connected world. We are referring to the integrated vertical ontology and epistemology that we worked out in earlier posts.

This is the most personally significant insight we've had. It was the response to our initial question of what can we know and how can we know it – the only way around the lies and misconceptions of the secular transcendent world we live in.

Reality consists of fundamentally different ontological levels that are accessible to us through different modes of knowledge production. Beast system deception – satanic inversion in general – often misapplies one to the other. Like believing empirical falsehoods about the material world on faith while pretending abstract truths are knowable materially.

Our simple graphic is hardly comprehensive. But it defines three broad interconnected distinctions and related ways of knowing in a way that makes it easy to keep them straight. And since we realized how ontology and epistemology are linked, it's become much easier to chase the truth. A lot of fog was burned off.

It is apparent from considering their historical footprints that geniuses on our epochal level perceive this integrated multidimensionality of reality intuitively. We can glimpse it and work it out systematically as a sort of graphic formula for clear thinking. For them it’s just reality. They aren’t going to bother with the diagrams like we do because they don’t need them.

If we are correct about Leonardo belonging in this company, two things will be demonstrable.

It is apparent from considering their historical footprints that geniuses on our epochal level perceive this integrated multidimensionality of reality intuitively. We can glimpse it and work it out systematically as a sort of graphic formula for clear thinking. For them it’s just reality. They aren’t going to bother with the diagrams like we do because they don’t need them.

If we are correct about Leonardo belonging in this company, two things will be demonstrable.

1. Leo expresses his intellectual vision visually

2. It is this vertically integrated ontology that makes his art so influential.

This means we have to look at Leonardo’s art on different levels if we are to appreciate what he has it say and why it was important to the arts of the West. Consider this change from the earlier Renaissance of previous posts.

Perspective was the signature breakthrough of the early Renaissance for

how to think about pictures, realism, and the representation of reality. Here's a good example.

All the lines moving away from you converge onto a central vanishing point. This limits the view but in that limited view renders space with such mathematical precision that artists could scale things to where they are supposed to be in depth. Click for a basic history of one-point perspective.

Jacopo del Casentino, Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple, 1330, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Remember how the medieval posts indicated how the illusion of space in art developed over the Middle Ages? Something like this was a spatial advance over the schematic flatness of the earlier Middle Ages.

We saw it as a general European trend towards increasing optical realism while maintaining symbolic references. Perspective must have seemed like the culmination of this process – an illusion of depth that captured the appearance of reality with mathematical perfection. So well that you could even adjust the size of figures to their exact relative distance.

The Ideal City painting up above came from a site with a helpful overview of perspective and pictorial space. They date the Renaissance from 1400-1500 - this corresponds to our placing the High Renaissance

at around 1500. There is an overlap – Leonardo starts laying the foundations for in

the 1480s while still working for Verrocchio. And Michelangelo does

similar in the 1490s.

Perception isn’t geometrically simple. Leonardo realizes this – optics are mathematical, but sight isn’t a one-point cyclops. It’s overlapping conic fields through curved lenses, and the world it’s looking at isn’t a flat regular plane. Every eye is slightly different too, so the ratios will vary. Perspective geometry is an ideal – it idealizes in that classical sense of abstracting and simplifying messier material empirical reality. It fits with the ontological level we call abstract reality – something of materially-impossible mathematical precision and regularity understood by inductive logic.

Johannes Vredeman de Vries, Perspective, c'est a dire, le tresrenomme art du poinct oculaire … The Hague, 1604–1605

Simplify out any identifying details and reduce the heterogeneity of human experience to an abstract mathematical grid. In terms of the ontological hierarchy, you are replacing the subjective material experience of the material world with an abstract rendering that doesn't reflect how we see.

The beast narrative takes perspective as Progress! towards modernity by claiming it is an application of a quantitative “scientific” paradigm to the world. This will later be problematized as a logocentric hegemonic Western gaze during the Postmodern seeding of current wokeness. But the real problematics – as we well know – come from this being the History! of discourse and not anything actually real. Who cares what the secular transcendentalists think? We’re comfortable in reality.

If you have high tolerance for the intersection of arrogance and idiocy, here's a Postmodern take on the "theoretical" meaning of perspective.

Start with a vacuous projection of Alberti onto psycho-sociology and degrade. Near-infinity to one the good "doctor" knows little about physiology of perception, cognitive science, Renaissance social and art histories and other knowledge domains he butchers. Don't even think about epistemology. But he does cite some gasbags...

The Postmodern argument is that perspective represents a false faith in the certainty of vision. This seems analogous to the false faith in the certainty of texts argued by Derrida and the deconstructionists and consistent with the Postmodern "thinking". It's even true to the extent that the belief that ontological absolutes can be conveyed in their fullness through subjective finite means is a ridiculous fake faith. But that's secular transcendence - mass projected vanity - and not anything to do with reality. Useful for blowing up webs of nonsense perhaps, but we're well past that.

If we want to consider perspective as a metaphor, we have to be historically and ontologically credible. That others aren't is the long-running collapse of higher education in a nutshell. Perspective is the spatial version of that same abstract logical order implied in all the variations of idealized classical geometry. It's more abstract because it is diffused into the representation of the world and not the shape of concrete things in it. But it's the same transfiguration from the material and temporal to timeless abstract perfection.

Attributed to Fra Carnevale, The Ideal City, early 1480s, oil and tempera on panel, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Another ideal city scene. According to the museum webpage, it exemplifies Renaissance ideals of urban planning, respect for Greco-Roman antiquity, and mastery of central perspective". The ideal representation of the ideal human order as Renaissance humanists saw them.

The great thing about these ideal cities is that they show the connection between perspective and simplified geometric forms very clearly. There's no story to distract and figures are incidental. Objects are reduced to simple polyhedra and space to a simple inverted rectangular-based pyramid. It does indicate the real world perfected that was the backbone of classical art theory. But it's artistically limiting and it lacks deeper harmony between elements. Here's some typical Renaissance perspective painting.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Herod's Banquet, 1486-90, fresco, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Ghirlandaio again. He makes for a good example of art right before the High Renaissance because he was highly successful. Plus we like his painting. See how the building is organized around the central perspective. Opening up the back removes the problem of dealing with the vanishing point by switching to open landscape. Herod's head is at the exact point - he's the center of attention.

Look at the Herod's Banquet again. There is a stark distinction between the “things” - the people and other objects - and the space. And there’s no obvious way to make them seem more integrated because the two are conceived separately from the start. Design the perspective stage, then paint in the stock figures. It was efficient for big projects and looked good enough, but wasn't the kind of medium that was going to put painting on par with philosophy. Or even poetry. It's great for illustration, and you can combine references to make associations - like putting a Gospel scene under Renaissance barrel vaults to assert the importance of the "Classical" humanist component. But the figures feel disjointed, like alien visitors.

What Leonardo’s new painting does appears to do nothing less than completely rethink this from the ground up in a way that visualizes the infinitly greater harmony of what we call a fully vertical ontology.

Leonardo doesn’t copy classical art, but he invents a new painting that expresses the same values.

Starting with his figures and building out instead of his perspective space and filling in is the same knowledge process that we introduced as a counter to the top-down jackassery of Rationalism, Postmodernism, et. al. way back at the beginning. The logical integration in his material techne is his way of conveying the unifying vertical Logos in reality.

As with everything Leonardo, the new art starts with painstaking drawings.

As with everything Leonardo, the new art starts with painstaking drawings.

Really look at this grouping. The figures flow together, heads and legs align, and the overall effect is harmony without repetition. Real and ideal.

He starts by designing his figures as an integrated group. They are individuated, but the unity adds a higher harmonious order to them. This differentiates the painted figures from real people who don’t fall into ideal patterns. Meta-harmonies that are only possible in painting can create a more simplified and harmonious vision than reality. This, as we know, is considered idealizing in Renaissance classical terms. Any classical terms in the West that draws on Greek metaphysics.

Since we're signifying absolutes in material ways, the more ideal, the more it depicts Beauty.

Leonardo, Study of St Anne, Mary, the Christ Child and the young St John, between 1501 and 1506, pencil, pen and ink on paper, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

Different kinds of drawing for different purposes. Here's a rougher sketch of a different arrangement. You can see his thinking - how some parts are clearly defined and others lost in showy unity.

The space is then sketched in around the figures.

The heavy reliance on preperatory drawings and drafts to figure out how best to arrange these ideal harmonies is a central feature of the High Renaissance. Since you aren't just copying reality, the drawing lets the artist work out how to bring realistic features into a higher, more ideal perfection. Drawing becomes the backbone of academic art training in the centuries that follow.

Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for the Virgin and Child with St Anne and the infant Baptist, and some studies of machinery

Here's a really rough sketch for a group - a few outlines and massing. Even in the roughest conceptual stages, he's thinking about the larger harmony. But he's also sensitive to the demands of the individual figures - on the right, the integrated massing, on the left working out the anatomy of a child in that pose. Both are needed.

One of Leonardo's crossovers from his empirical observations to his art was the role of light in defining forms. There were cast shadows in earlier Renaissance paintings, but the spaces tended to be evenly lit and the figures defined by drawn outlines.

Consider - Leonardo wants to sublimate his figures to a higher ideal unity. But he is also the most empirically realistic artist we've seen. You achieve both by using light to define figures out of the shadows. This is how we really see, and the areas obscured by darkness also allow for simpler, more integrated groupings.

Here's a preparatory draing where he is studying how the light and shadow falls. This determines what parts have to be clearly defined, what is hidden in shadow, and where the transitions are.

There's enough detail to rough out where the realistic parts are.

And the shadowy massing lets him sublimate the whole complex group to that stable simple geometry that the Renaissance Classical ideal was built around.

The detailed realism was also served by drawing. Objects and live models were studied and worked up through preperatory sketches of different kinds. This gave drawing an intellectualized component - the part of the artistic process where the artist takes his observations of the real world and transforms them into more ideal forms.

Leonardo, Study for Madonna and Child with St Anne, black chalk, wash and white highlights on paper, between 1503 and 1517, Louvre Museum

Here's a surviving example of one of Leonardo's more detailed detail studies for the same project.

The problem is that this took so long - probably because he was engaged in rethining the relationship between art and ontology. By the time it develops into Academic art, the methods had been turned into formulas.

His arrangements are so impossibly profoundly eloquent - that was the upside of spending so much time pondering each stroke of the brush or pencil. We've looked at a lot of all-time heavyweights of drawing - Pisanello, Michelangelo, Dürer, Holbein, Rubens, Van Dyck, Poussin, Goya, Ingres, Dore, van Gogh, Bouguereau - no one wove each piece, their connections, and their place in a grand ontological unity with such a feeling of depth. Even Raphael - in our opinion a better draftsman - compromised the extreme profundity for his blistering speed.

The close-up is kind of unbelievable. The way he builds the bodies and faces from light and shadow...

But the unity goes beyond the blended forms. Anne, Mary, and Jesus' heads form a nice triangle. Or the line through Mary, Jesus, and John.

Then look how Jesus' gesture of blessing - a sub-interaction between him and John flows into Anne's upward-pointing hand. A direct reference that Jesus' action is his Father's.

All kinds of material logos and beauty, guided by abstract logos and beauty, and flowing to Logos and Beauty.

This level of thought and construction is why it is so moronic to pretend you can treat a painting like this as a snapshot. There is nothing real about it. Realism != real. Quite the opposite. Aspects of it pass as “real” but the thing is as constructed and artificial as a haiku. That people try and “read” these as photos is an indication of how rhetorically powerful they are.

The short answer is that he pretty much figured out how to apply a newly-forming sense of the classical ideal for painting. And since the classical ideal is not unrelated to the Band’s definition of the art of the West – what Leonardo does is express a vertically-integrated ontology that is consistent with the classical values of realism and idealism without following classical models or looking classical style-wise.

The short answer is that he pretty much figured out how to apply a newly-forming sense of the classical ideal for painting. And since the classical ideal is not unrelated to the Band’s definition of the art of the West – what Leonardo does is express a vertically-integrated ontology that is consistent with the classical values of realism and idealism without following classical models or looking classical style-wise.

That's a familiar formula...

The next question is what is the classical? Probably seen enough to know it’s a complex beast of a term. Click for a brief historical overview. We just need to know what the basic features of Western Classicism are, and how Leonardo invents a form of painting that can express them perfectly.

Many cultures have a classical phase – it’s a noun when referring to a particular era. Otherwise it’s an adjective referring to certain attitudes towards tradition, the past, and order. In the West, this is connected to Greco-Roman antiquity – the noun form of Classical in our cultural history. Click for a post.

Many cultures have a classical phase – it’s a noun when referring to a particular era. Otherwise it’s an adjective referring to certain attitudes towards tradition, the past, and order. In the West, this is connected to Greco-Roman antiquity – the noun form of Classical in our cultural history. Click for a post.

Joseph-Marie Vien, The Cupid Seller, 1763, oil on canvas

Classical as historical attitude - thoughts about the past and ideological position in the present are related. Classical attitudes towards culture expressed in classically-defined forms.

Classical as historical attitude - thoughts about the past and ideological position in the present are related. Classical attitudes towards culture expressed in classically-defined forms.

Even the light themes of love and romance are lessons in proprienty and decorum.

Getting to the classicism of High Renaissance art. Take the David.

Michelangelo, David, 1503, marble, Accademia, Florence.

Michelangelo is the only artist with images as famous as Leonardo’s greatest hits – mainly this and the Creation of Adam. If the Mosa Lisa is the best-known painting of all time, this is the best-known statue.

We’re still figuring out Leonardo – Michelangelo will wait until the next post.

One thing that is clear is that as a sculptor – he did all the arts, but sculpture was his background – he had a different connection to ancient statues. It’s the same art – marble carving hasn’t changed much since antiquity. Renaissance metallurgy was better so the chisels and files didn’t need sharpening as often. Otherwise, it’s the same. Even modern sculptors aren’t that different. Power tools make some of the rough work faster, but they’d find themselves weirdly at home in an ancient workshop.

Then there's the issue of the nudity. Time for a...

The David is a Biblical subject but he is carved like a young classical

athlete. The head is a little large proportionally, but the statue was

designed for the wall of the Florence Cathedral and would have been

seen from below. From that angle, the proportions are more “perfect”.

And the contraposto pose is right out of antiquity from any angle.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pygmalion and Galatea, around 1890, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ancient Greek art reflects a very different attitude towards carnality and nudity than late medieval Italy. Set aside the hedonistic aspects of classical physical culture, homoeroticism, Dionysian ritual, theatrical catharsis, symposia, etc. There is definitely an erotic element to ancient nudes – and this extends to the female before long.

The story of Pygmalion is about a sculptor falling in love with his statue and her miraculously coming to life. Put aside the magical climax and it's about the erotic allure of the beautiful nude body - even a marble one.

The small genitals are the tell. This Greek idealism differentiated the animal and bodily from the spiritual and intellectualized and the David does the same. The perfect, powerful body expresses a higher ideal – that is demonstrably not a sexualized thing. The contrast is obvious when we look at one of the numerous satyr, Priapus, and other natural “fertility” types that survive.

Priapus, 1st to 3rd century AD, Imperial Roman bronze with phallus and serpent, private collection

Easy to see the contrast.with the David. The overt Roman phallus obsession didn't make it into the Renaissance.

Michelangelo wasn’t a Neoplatonist, but the influence was strongest on him early in his career. He spent some formative years as a young artist in residence with Lorenzo the Magnificent de Medici when Ficino et. al. were running their Platonic academy. His main interest seems to be the Medici sculpture collection, but Neoplatonic ideas permeated the house. The David certainly reaches for that kind of beauty.

When you consider that the Humanists were fusing Christianity, Neoplatonism, and even Hermeticism into blasphemous hybrids, it’s not hard to see the David as the sculpted equivalent of the same idea. Doesn’t mean it’s intentional. Michelangelo’s involvement in the Platonic Academy appears to consist of sitting in on some lectures and what he got by osmosis as a youth. He went on to become an increasingly passionate Christian. But it’s fair to say that the art and the philosophy reflect a larger cultural attitude. One where humanism was diluting Western Christianity – by adding pagan authority to the theology and pagan aesthetics to the morality.

When you consider that the Humanists were fusing Christianity, Neoplatonism, and even Hermeticism into blasphemous hybrids, it’s not hard to see the David as the sculpted equivalent of the same idea. Doesn’t mean it’s intentional. Michelangelo’s involvement in the Platonic Academy appears to consist of sitting in on some lectures and what he got by osmosis as a youth. He went on to become an increasingly passionate Christian. But it’s fair to say that the art and the philosophy reflect a larger cultural attitude. One where humanism was diluting Western Christianity – by adding pagan authority to the theology and pagan aesthetics to the morality.

Or dispensing with the morality altogether.

Humanist drivel was the cover for the birth of the pin-up – highly eroticized images for the growing private collections of Europe as “Venuses”. The same qualities that lined Venetian painting up with color, texture and emotion in the discourse was perfect for this. The position, flushed expression, and modern setting make it clear that this one of Venice’s famous courtesans.

Later mouthpieces legitimate the nonsense with canards like the naked

and the nude, then wonder why no one cares when the Postmodernists

drummed them out. The paintings could he very alluring- even beautiful -, which doomed them in a beast system that promotes ugliness over all.

Alexandre Cabanel, The Birth of Venus, 1863, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay

The Band's take? Art is an material human creation that expresses truth about human nature, values and experience. And Christian logos is different from Classical episteme in that it ties different ontological levels together with different forms for each. The female form is magnetically attractive, the paint is stunningly handled, and Venus is a huge part of the Classical heritage of the West. The problem - like everything in this fallen material world - revolves around intention. Moral reasoning. Is the primary painting of the painting intended to arouse? There is a base animal truth in carnality, but it's hardly the stuff of phronesis.

It's easy to forget looking at the modern history that the default morality in the Renaissance was Christian. The Reformation hadn't happened - there was just Western Christendom. For all the hedonism, pagan fixations, and occultic weirdness flying around, society was far less openly tolerant of perversion.

Michelangelo, Crucifixion, black chalk, 1538-1541, The British Museum, London

Private drawings and works are a good way to get at artists' personal feelings. Michelangelo made religious drawings of remarkable intensity. In this one we can see his preferred mode of communication - a powerful nude figure - expressing his own spiritual yearning.

Michelangelo, The Deposition (The Florentine Pietà), 1547-1555, marble, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

This unfinished work was intended for his own tomb. According to the story, the aging sculptor was unhappy with the piece and tried to destroy it. His students talked him out of it and fixed up as best they could.

The point is that he carved his own face on Nicodemus in the background as testimony to his devotion.

Christian attitudes towards nudity were different from the ancients. This put Michelangelo and other Classically-inspired artists in awkward situations.

It was conventionally assumed that nudity was a prelapsarian condition – unfallen man in a natural perfection akin to the Greek sculptural ideal. But the Fall changes this in a way it didn’t in Greek thought – some form of shame and sexual modesty were hallmarks of every national form of Western Christian morality. Flaunting physical allure was immoral, regardless of proportions or tastes.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Adam and Eve panel from the Gates of Parardise, 1425–52. Gilt bronze, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

Always worth revisiting Ghiberti's masterpiece. Scenes of Eden let artists have it both ways - represent nudes and stay in alignment with Christian morality.

The Creation of Eve is a stunning bit of metalwork.

The first couple in unfallen nudity. Clothing on the figures representing God and the angels indicates decorum applies - the purpose is to comment on the human state in particular.

Shame comes after the Fall.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, David panel, from the Gates of Parardise, 1425–52. Gilt bronze. Collection of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo

Once out of the garden, the regular rules of morality and propriety are in effect.

Since Michelangelo's David started this side-discussion on classicism and nudity, here's Giberti's earlier Renaissance take on him and a close-up. The young king and his enemy are both appropriately dressed.

The Band sees this as akin to any moral Trojan Horse – we are not unfamiliar with canards about artistic merit around degeneracy. At the same time, we are also adults and created in God’s image. We can understand the discourse and discuss what is happening artistically. But we can’t justify the blatant nudity in religious imagery. The loincloth is fine for church and put the idealized physical beauty in the art museum. This doesn't invalidate the sincerity of the Renaissance classicists. We just disagree on the fitness of appropriating the idealized aesthetics of classical nudity to Christian art - no matter how well intended.

That said, we do have to deal with it, and it seems to us to be another place where the split between art and Christianity formed.

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna in the Forest, around 1460, oil on panel, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

Nude images of the Christ child seem to be a way to make him more emotionally relatable by playing up his human side. There's clearly something unearthly about them, but he looks a lot more like a baby than the little emperor in earlier paintings.

The nudity of a baby would have had a very different impact than an adult man.

The point is that the nude was something that only appeared in very limited and specific circumstances in the earlier Renaissance. It's the impact of ancient art that propels it into he mainstream. And this is a major split between the moral tenor of the arts and the general public. There's a big difference between the occasional infant or Eden scene and the centrality of nudity in ancient art. Keep in mind that it wasn't seen as an assault on morality by the artists, but that is irrelevant - the narrative engineers of modern History! can easily write the reappearance of nude statues as a giant leap for Freespeech!

Opening the door - even a crack - to pagan sexual morality would be the next big step in the development of Art!

We're tracing art, so consider how the classical was brought over into a Christian context. It has to be acceptable before it becomes subversive - the art is like secular transcendent thought in general. We say in earlier posts how Christian humanism introduced pagan - that is, human - authorities into morality and ontology and broke the metaphysical unity of medieval society. Art does much the same thing. And like most satanic tickets, taking it seems like a good deal at first...

There are two big components to the Renaissance art version of Classicism. The first is the proto-theory derived from those parallel developments in humanist letters. Everything from pedestalizing ancient culture to emulating specific texts like Pliny and Vitruvius. The written art theory that starts to appear in the Renaissance - like Alberti in the 15th century and Vasari in the 16th - are the most obvious expressions of this.

The second component comes from the real surviving works of art - mainly statues and structures that show what the ideals in the ancient texts looked like. A huge part of Renaissance classicism comes from the appearance and feeling or aura of ancient sculpture - ancient painting didn't really survive and mosaic wasn't one of the Renaissance fine arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. But a lot of statues did, and these got more and more valuable as humanist ideas took over art. Both among wealthy collectors and artists and theorists looking for models. Click for a good short intro to Greco-Roman art with excellent examples. Like this one...

Apollo Belvedere, Roman copy from 120 - 140 AD of Leochares' bronze of around 350-325 BC

It’s easier to see the classical aesthetic - any aesthetic, really, than describe it. The Apollo Belvedere was the epitome of Neoclassical beauty and highly admired in every era since it’s rediscovery in 1489. It was first acquired by Pope Julius II before he was pope and added to the Vatican collection that he opened to the public in 1511. It’s still there today. It is not an exaggeration to call this one of the most influential images in the history of the arts of the West.

It's vision of flawless male beauty is lean and athletic - typical of the Late Classical or Hellenistic ideals of Leochares' time. This obviously isn't suitable for every subject, but the legacy of ancient sculpture was vast, and there were lots of models for different types.

Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer), Roman copy 120-50 BCE of original by Polycleitus of around 440 BCE

The grandfather of proportioned Classical contrapposto. The Roman marble copies that survive - like this one - are probably blockier than the original. Regardless, they were models for serene, flawless figures with more powerful builds.

Neoclassicals weren’t as aware of the distinctions in ancient art as we are because they couldn’t benefit from thousands of photos and two centuries of archaeological finds on the internet to look at. They were planting the acorns of future knowledge for readers they’d never know. The Apollo Belvedere was one of the pieces that really was recovered in the Renaissance but this copy of the Doryphoros was from Pompeii. That is, recovered by Neoclassical archaeology. We rightfully pillory auto-idolatrous Enlightenment absurdities, but we are grateful for the empirical legacy. It’s why we can build again.

There was even less awareness of ancient art and history than the Neoclassicals had in the Renaissance. A brand new appetite for ancient art in the new humanistic culture – the Apollo Belvedere is a good example. But the technical knowledge wasn’t there yet.

There was even less awareness of ancient art and history than the Neoclassicals had in the Renaissance. A brand new appetite for ancient art in the new humanistic culture – the Apollo Belvedere is a good example. But the technical knowledge wasn’t there yet.

Antico (Pierre Jacobo Alari Bonacolsi), Apollo Belvedere, 1497 or 1498, bronze, partially gilded, eyes inlaid in silver, Liebieghaus Museum, Frankfurt

Antico made a career producing high-quality miniature copies of ancient statues in expensive materials to aristocratic clients. Like this one. He's a fine sculptor - but the interest is aristocratic and aesthetic, not antiquarian.

Antico made a career producing high-quality miniature copies of ancient statues in expensive materials to aristocratic clients. Like this one. He's a fine sculptor - but the interest is aristocratic and aesthetic, not antiquarian.

Archaeology wasn’t much more than humanist amateurs and art sellers poking around ruins for finds and whatever the farmers and workers dug up as the city grew again. Of course, the city was growing over what had been imperial Rome, so while the historical knowledge may have been limited, the material discoveries were astounding. Recovered antiquities were like a steady classical stylistic infusion into the artistic bloodstream. The transition from the conception of the nude in Michelangelo's David to the figures on the Sistine Chapel doesn't happen without the influence of recovered Hellenistic works like this all-time masterpiece...

Michelangelo was on hand when this was found in 1506 – part of the group Pope Julius sent to assess the work and arrange for it's purchase if worthy. It’s still in the Vatican collections too. The technical excellence is remains stunning - it looks like the Pergamene style that was the toast of Hellenistic Eurasia. Michelangelo was overwhelmed by his first encounter with skill that rivaled his and emotional power that exceeded it.

But he had no way to look at the these three as signature examples of the Classical, Late Classical, and Hellenistic periods of Greek art like a modern textbook. It was all “ancient sculpture” at this point, and a level of the art beyond what they were used to. Not just technically – ideologically, as a perfect, secular transcendent fit with the classical theory that was developing from the ancient texts. Just hold on to this thought...

the question of what ancient models will turn the study of the past into aesthetic ideology

You can see the influence of the Apollo Belvedere on Michelangelo's David. Michelangelo’s anatomy and psychology is even better, but it’s

still clear to see that he subscribes to a similar belief about art,

realism, and what constitutes an ideal.

But here’s the problem. It’s all sculpture.

What does “Classical” painting look like?

Seriously. The ancient art posts where we worked out our definition of the art of the Was all statues and buildings. The didn’t know about Pompeii. The Roman interiors that they could see didn’t look anything like classical sculpture. Didn’t idealize reality either

Domus Aurea, around 64-68 AD, rediscovered, 15th century

The Golden House of Nero triggered a vogue for interior design but didn't have much in common with the aesthetics in any of the statues. Doesn't look much like the individual paintings we've seen either. There was nothing here to guide altarpieces or chapel frescos.

There's the problem - you can see the kinship to ancient statues in the sculpture of the Renaissance. What would “classical” painting look like?

Leonardo is an inflection point in the art of

the West because he answers that question.

He is epochal because his life embodies what came to be thought of as the intellectual culture of the Renaissance. Not the secular transcendent landmark on the road to PROGR version, but the whole contradictory mess of it. And because he presents that through his art, his work has a profundity that changes the culture meaning of art itself.

Leonardo does present some problems for a logos-facing perspective. Some of his later pictures have a degenerate air and his own sexuality raises questions.

Leonardo da Vinci, St. John the Baptist, between 1513 and 1516, oil on panel, Louvre Museum

When enlightened glow gets homoerotic.

When enlightened glow gets homoerotic.

Our interests are - as stated aleready - how he sets the course for his cultural moment and his impact on the arts of the West.

It is true that personality is relevant to painting, despite what modernism said. So lets emphasize that neither our assessment of Leonardo’s artistic

skill or intellect are an endorsement of him as a role model or life coach.

That said, there are elements of Leonardo response that are retarded to the point of being impossible to ignore. Like whether or not the Mona Lisa resembles Leonardo. Anyone ever seen Leonardo?

Leonardo, Self-Portrait, around 1512, red chalk on paper, Biblioteca Reale, Turin

The famous drawing believed to be his self-portrait. Two questions to sift out the retards.

1. Are you aware of the differences between a drawing and a photograph?

2. Do you know what an artist's style is and how is effects what their work looks like?

If you can answer these, there is no need to explain why it takes a special kind of stupid to speculate on whether the Mona Lisa looks like him.

And if you can't...

More seriously, the Mona Lisa was a painting he carried with him his whole life. He probably never stopped tinkering. It’s like a lab for his ideas about light and shade – a place to experiment, not a portrait. Fixating on the bone structure of a painting of this kind is akin to guffawing about a chipped tile on the path to the Taj Mahal.

Readers know that the Band is happily free of retardation, so enough on that.

Readers know that the Band is happily free of retardation, so enough on that.

So looking at his art. The first problem - the Leonardo bibliography is insane, with new material coming all the time. Usually we have the opposite problem. Something catches our attention that we can’t place, but when we try and look it up, there’s no information. Quickly looking up Leonardo is like trying to sip from a firehose. He has so many facets and has captivated people for so long that there are almost as many Leonardos as there are commentators. Calling him an empirical observer is like saying Usain Bolt has a quick step. At the extremity of human ability, descriptions fail. Leonardo’s observations seem unreal at times. Like retinal lensing. Or water movement.

Leonardo noted the three-dimensional nature of eddies in flowing water varying in scale from large to small - A.N. Kolmogorov’s “cascade model of turbulence”. You can see his comprehension in the comparison with the computer particle tracking model. But Leonardo’s perception of the connectedness of things led him to a similar pattern in hair.

Studies of water passing obstacles and falling, c. 1508-9; Visualisation of the instantaneous flow field in the ‘unsteady bubble’

wake at 𝑡/𝑇=4.2; Streamlines seeded close to the bed and coloured by

elevation; head of Leda Click for image and Leonardo quote sources

We’re no different in picking a Leonardo – art pioneer or epochal mind are just two elements of his life. With little to say about his biography and social connections, political activities, sexuality, military strategy and architecture, flood control and water management, collaborations, gifts in other arts, or any other of his countless facets. Click for a few more of his ideas.

These were the main books we read for these posts: the current big name academic, the art history classic, the biographer de jour, and a complete works. The last may be the most important because Leonardo speaks visually.

We scanned the general on-line resources to get a handle on the main points in his life and how he is understood. Enough to get a sense of his basic parameters because the minutia is quicksand and most is not publicly accessible. Then we turned to his art. There aren’t many paintings to look at, but there are boatloads of drawings in the notebooks that are easy to find.

We don’t need a complete grasp on him to read the paintings. We just need to be clear what we are looking at and the core information – what the subject is, what the symbols referred to, the sequence they were done in. Then we take what we’ve observed about the art and culture of early Renaissance Italy as the context in which his activity plays out. Readers know that while Leonardo may dwarf us in totality, our ability to visualize ideas is not trivial. It also dwarfs our baseline intelligence. So we can pit our perception against Leonardo’s expression to get at what is going on in the paintings. We aren’t trying to grasp the totality. We can’t. Only the epochal vision and the implications for art.

We don’t need a complete grasp on him to read the paintings. We just need to be clear what we are looking at and the core information – what the subject is, what the symbols referred to, the sequence they were done in. Then we take what we’ve observed about the art and culture of early Renaissance Italy as the context in which his activity plays out. Readers know that while Leonardo may dwarf us in totality, our ability to visualize ideas is not trivial. It also dwarfs our baseline intelligence. So we can pit our perception against Leonardo’s expression to get at what is going on in the paintings. We aren’t trying to grasp the totality. We can’t. Only the epochal vision and the implications for art.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Madonna of the Rocks (first version), 1483–1486, oil on panel (transferred to canvas), Louvre, Paris

The last post introduced The Madonna of the Rocks – it's a familiar image for introducing some preliminary observations before tackling the big three.

The last post introduced The Madonna of the Rocks – it's a familiar image for introducing some preliminary observations before tackling the big three.

Why is Leonardo such an innovative artist?

He invents a way for painting to meet the paradoxical demands of Classical aesthetics – realism and ideality in the same image. One that ties to the beauty of holiness and the traditional uses of art at the time.

This isn’t copying or reviving ancient art forms and styles. Painters didn’t have the surviving examples of Roman art to copy that the sculptors did. And techniques like perspective were new. What they had were ideas pulled from ancient texts about realism and ideal beauty. The mimesis described by Aristotle fits theoretically – a creative imitation that perfects as well as replicates something. It reminds us of Tolkien’s sub-creation in a way, with a more general intensification of central elements taking the place of idealism.

But what would this look like in the language of 15th-century Renaissance painting? Reading what Apelles did doesn’t let you see it. Leonardo showed how with paintings like this one. More realistic in the details and effects than ever before, and with a timeless, ideal air of perfection that was equally radical.

But what would this look like in the language of 15th-century Renaissance painting? Reading what Apelles did doesn’t let you see it. Leonardo showed how with paintings like this one. More realistic in the details and effects than ever before, and with a timeless, ideal air of perfection that was equally radical.

Domenico Ghirlandaio and shop, Virgin and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist and Three Angels, around 1490, Louvre

Ghirlandaio is a good comparison - a leading artist of the former generation, and Michelangelo's teacher. Not hard to see that he is an awfully good painter - perfect benchmark for where Leonardo departs from.

Like any epochal mind, there is a perception of greater unity in reality. It appears in different ways here. Lke using water studies for the patterns in falling hair. Or the unprecedented atmospherically-correct effects of misty distance as empirical understanding of physical perception and a metaphor for the unknowable depths of divine mystery.

Or the intense realism and unearthly perfection of the hands

How do you describe the “perfection”?

You have to see it.

A general descriptor shows you where to look – like “the geometric arrangement” – but it has to be seen to be really understood. This is the idea of the paintings as manifesto. It visualizes how things fit together. The pattern – a greater synthetic understanding of natural and abstract realities churned in search of logical unity with God. That’s impossible to actually achieve, but the consolation for falling short prize is epochal – a new vision of logos in Creation that points to the necessity of the divine but can’t quite show it.

Like runway markers for a leap of faith.

Leonardo isn’t a Neoplatonist, but his vision is consistent with humanist Neoplatonic idealism. The idea that things become simpler and more harmonious and symmetrical as they rise ontologically towards the absolute oneness of God. This is the Classical theory of beauty as well, where ideal Beauty is one with the True and the Good.

By marrying the real and the ideal, Leonardo invents a new painting that perfectly realizes Classical values and gives art an inherent moral dimension.

Goodness via Beauty via Truth. Compare the Madonna of the Rocks to the David. It's easy to see the different connections with ancient art. Michelangelo's looks like the best ancient contrapposto ever. Leonardo's doesn't look ancient at all. More importantly, Leonardo's version of the "Classical ideal" differs from the ancient sculptural and Michelangelo's version in ways that are specific to painting as an art form. It's build around a harmony of arrangement that doesn't even apply to statues beyond figural proportions and poses. If each fine art is to have it's own secular transcendent theory to distinguish it, this is a start.

It's communicative too. The moralizing in the moral content – the stories – is reinforced by the beauty of the formal arrangements as well. They complement. Look at the Ghirlandaio comparison again. Leonardo is more realistic in figures and details – the real - and more perfectly and flawlessly structured – the ideal. And look how much more unified the space and the figures are. Ghirlandaio’s are disconnected from the background in comparison.

Leonardo’s aren’t just exquisitely arranged – they form a rational spatial group at the center of the painting, with the background planned around them.

Things of unprecedented realism arranged into a more perfect order” – only without the occult ties.

Like Thomas and Newton, Leonardo was a Christian, even with some ideosyncracies. This is a trajectory from the messy material world through higher abstraction and towards an unshowable absolute. Sounds familiar…

Right. It's our formula of based on the Greek terms for a working definition of the art of the West. Including the connection to logos. How sweet is that?

And he does it by synthesizing the legacy of the late Middle Ages and Renaissnace into something new. All together, it looks familiar…

His art was a goal and a tool. A goal in that he constantly refined and worked on it and it provided him with income and celebrity that freed him from ordinary constraints. The Madonna of the Rocks is his second crack at the same subject and the Mona Lisa was with him all his life.

The mastery of oil and new techniques, all the observation and study of light and shadow, space and perspective, optics and composition, the mastery of drawing – all part of a life spent refining and improving his art on every level.

The mastery of oil and new techniques, all the observation and study of light and shadow, space and perspective, optics and composition, the mastery of drawing – all part of a life spent refining and improving his art on every level.

Gradations of primary and derived shadows, Ms. Ashburnham II, folio 13v

One of many drawing of the effects of light and shadow, and what understanding them did for his ability to model illusory volume. And paint convincing shadows in his backgrounds.

One of many drawing of the effects of light and shadow, and what understanding them did for his ability to model illusory volume. And paint convincing shadows in his backgrounds.

Then working it out in his drawings - like this head of the Madonna in the Virgin, Child and St. Anne - before moving on to a painting.

His level of preparation was highly unusual. What you'd expect from a singular genius rethinking visual representation.

But developing this high-powered art also gave a tool for exploring the deeper unities behind the complex reality he was studying. It's reciprocal - studying nature refines the art, refining the art studies nature. This is where we see the epochal mind that defines the High Renaissance.

Consider his three most famous works.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, from around 1503-1506, until c. 1517, oil on poplar panel, Louvre, Paris

The Mona Lisa has to be first. The most famous painting of all time – it’s very presence in Paris boosted French claims to cultural superiority.

It was started as a portrait of a Florentine banker’s wife but never finished. Instead he seems to have used it as a place to tinker and experiment with his paints.

It seems alive and unreal at the same time.

This picture captures the effect better than most. It clearly isn't a photo, but the sense of presence is eerie.

The smile and overall impression of life is unforgettable. Now we know why. Here is a link to an archived article drawing on Isaacson's recent biography. Isaacson is a globalist shill, but he is a through biographer, and describing Leonardo’s practices isn’t something where his inhherent political biases come in. And his account of the Mona Lisa certainly seems legit and is fascinating. He breaks down all the different factors that went into the picture. When we noted that Leonardo carried it around and tinkered with it, turns out we were selling it short. The conceptual unity tying together his countless interests are all here. Here’s the archived article that led us to the book.

Anatomy

Anatomical study is a natural link between art and reality for Leonardo. The classical ideal was based in part on realism - what better way to take that to new heights than to incorporate an unprecedented knowledge of the human body?

Leonardo, anatomy of the mouth c. 1508, traces of black chalk, pen and ink on paper, from Anatomical Manuscript B, British Library

Note that the same delicacy and precision that went into Leonardo’s drawing is in his dissections – the results of which are recorded in his notebooks. This hand-on to the point of pulling individual muscles to see how they moved the smile gave him an unprecedented understanding of facial anatomy.

Note that the same delicacy and precision that went into Leonardo’s drawing is in his dissections – the results of which are recorded in his notebooks. This hand-on to the point of pulling individual muscles to see how they moved the smile gave him an unprecedented understanding of facial anatomy.

No, not the "House of M". It's the abstraction of empirical observation and measurement into normative or idealized ratios in facial structures and measurements.

Remember, there are thousands of pages of this.

Optics

Leonardo's fascination with light and seeing connected to his interest in anatomy when it came to understand how sight worked. Click for a piece on Leonardo's basic ideas around perception, light, and physiology. Click for a good look at Leonardo's anatomy and how it connects to his understanding of optics. The second one needs a translate function if your don't read Portuguese.

We’ve mentioned his observations of light and shadow impacted his art in different ways. Understanding the gradient of lighting on a curved surface let him softly model facial features and contours. His oil mastery comes in here too – he used very dilute glazes and tiny strokes to make seamless changes in color and light.

We’ve mentioned his observations of light and shadow impacted his art in different ways. Understanding the gradient of lighting on a curved surface let him softly model facial features and contours. His oil mastery comes in here too – he used very dilute glazes and tiny strokes to make seamless changes in color and light.

Leonardo, A study of the fall of light on a face, around 1488, pen and ink, Royal Collection RCIN 912604

Came across this drawing where he is thinking about how light falls on an irregular surface like the face.

If we connect this to the anatomy drawings - they determine how the face is made and the optic ones show how we see it in the natural world.

Anatomy and optics overlap most strongly when it comes to his understanding of how we see. This includes inducing the lensing of the image in the eye and the existence of the fovea from observation.

It really is incredible. Here are a few of his relevant drawings and a quote.

The surface damage is visible in high res photos on the internet.

Although the paint has cracked, it's pretty much all still there. Unusual - a lot of Renaissance masterpieces suffered from ham-fisted "cleaning" attempts.

It actually could use a cleaning. But who wants the responsibility of mucking with the Mona Lisa? Easier to keep punting.

Then he models the features with light and shadow instead of more linear outlines. Combined with the smooth transitions, it appears to the eye the way a real face would. It’s not a photo in its realism, but it registers to our eye even more naturally.

According to Isaacson, the smile comes from the shadows around the mouth. Because Leonardo understood the difference between direct and peripheral vision, he painted the shadow so that the mouth looks smiling peripherally and more serious directly. Since you see it from different angles in real life, it seems to smile as you turn away. The perceptual trick gives the illusion that the painting moves as you do.

There’s probably more to it than that even, but this is good enough to show how connected Leonardo’s world is.

To get the Mona Lisa to register as so real, he used his understanding of perception, sfumato and modeling with shadow, facial anatomy, some psychology, and tremendous skill with a new way drawing and painting.

He’s even using a new kind of pose. The traditional Renaissance portrait was done in profile to look like Roman coins and medals. The idea of portraits - commemorating material life for posterity - was inherently of Classical humanistic origin. So the medallion look was the thing in the earlier 1400s. Leonardo introduced the pose with the shoulders oriented diagonally and the face turning towards you. It made the figure seem more alive and real. As if capable of movement or even speech. Plus it gave a full-face likeness. Not surprising it became the norm for Western portraiture.

Here's one of the first appearances of the new pose from some 30 years earlier. Notice how much less adept he was at building a real face out of light and shadow.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de' Benci, c. 1474–1478, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

This painting of a celebrated young humanist got cut down at some point - it used to be longer like the Mona Lisa. You can see how far he came in building a real face and capturing the subtleties of expression. But you can see the same flat, round facial type underneath.

Then there's that relationship between the figure and the setting. In both portraits the landscape is built around the person to enhance the representation. The Ginevra de' Benci uses the juniper - a play on her name that the erudite Benci appreciated - to highlight her face. The airy background is his first use of mysterious and evocative landscape depths to indicate similar complexity in the sitter.

Then there are the depths of the Mona Lisa.

Consider how the appearance of life and the ambiguous expression made the Mona Lisa captivating. The background complements and amplifies that intrigue.

In assessing what this tells about Leonardo's epochal vision we have to ask what a portrait meant to him? The answer is clear - a likeness of a real person. The most material of subjects. The figure synthesizes and refines the innovations of the earlier Renaissance - figure types, oil paint - so that it registers as real and deep in a way that was new. Intense empirical observation and the most refined techne combined in generally applicable insights into material logos – on a natural and human level.

That's a start. Time to climb the ontological ladder.

The next image does just that. The Vitruvian Man is a drawing – a humbler medium, but one that abstracts the intense natural logos of the Mona Lisa into the realm of ideal idealized geometric abstraction that humanists grooved on.

Leonardo, Vitruvian Man, circa 1492, pen, ink and wash on paper, Gallerie dell'Accademia

Unlike the Mona Lisa this one only got famous later. It was a drawing in the notebooks - something Leonardo did while thinking about humanist architecture in Milan with Bramante.

It takes the material level of logos that the Mona Lisa captured so perfectly and elevates it to the level of abstraction.

The close-up from a high-res scan shows the texture of the paper.

Synthesizing the prior era - note that the same proportions that mark the ideal human form are the ones that represent earthly and cosmic order.

Remember Bramante's St. Peter's from the last post?

Circle over square in cosmic harmony.

The Mona Lisa gave us a glimpse of the abstract through the material / human. This gives us the connection between the human and the abstract. And the Last Supper the human and divine

The next household name image is The Last Supper.

Leonardo, The Last Supper, 1490s, Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

It’s a wall painting but not a fresco – one time Leonardo was too smart for his own good. We assume that his decision to try and invent a new form of wall paint was because he was dissatisfied with the color and light effects were possible in fresco. The painted plaster was very durable, but the water-based paints weren’t as vivid and versatile as oils.

Whatever the reason, the new formula failed miserably and was peeling almost immediately. Then factor all the subsequent damage, and there isn’t much of the original paint still there.

The ghost forms still captivate, but of the subtle delicacies of the Mona Lisa were present, they’re long gone now. The Mona Lisa needs a cleaning, but all the paint is there.

It’s a wall painting but not a fresco – one time Leonardo was too smart for his own good. We assume that his decision to try and invent a new form of wall paint was because he was dissatisfied with the color and light effects were possible in fresco. The painted plaster was very durable, but the water-based paints weren’t as vivid and versatile as oils.

Whatever the reason, the new formula failed miserably and was peeling almost immediately. Then factor all the subsequent damage, and there isn’t much of the original paint still there.

The ghost forms still captivate, but of the subtle delicacies of the Mona Lisa were present, they’re long gone now. The Mona Lisa needs a cleaning, but all the paint is there.

Here's a close-up of the damaged surface. You can just get a hint of that incredible figure modeling seen in the Mona Lisa or the Madonna of the Rocks.

So why the appeal here? Part of it is the fame of Leonardo’s aura, but a small part. And if it’s not the now-gone details, it must be the overall impression of the design. It’s the arrangement or composition that makes the lasting impact.

Start with another innovation. In the Mona Lisa the whole work is conceived as a unity, but because it’s a close-up portrait, the details of the figure dominate. The Last Supper is a narrative scene with multiple figures arranged to best communicate the meaning of the story. Like a larger version of the Madonna of the Rocks. Where how the parts are arranged reveals the deeper metaphysical meanings behind appearances.

Andrea del Castagno, Last Supper, 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Last Supper, 1480, fresco, Ognissanti, Florence

Last Suppers were a common subject as part of life of Christ cycle and the foundation of the Eucharist. The standard approach was to show the figures lined on one side of a table so no one has their back to us and Jesus is central.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Last Supper, 1480, fresco, Ognissanti, Florence

Last Suppers were a common subject as part of life of Christ cycle and the foundation of the Eucharist. The standard approach was to show the figures lined on one side of a table so no one has their back to us and Jesus is central.

Leonardo’s innovation started with his choice of narrative moment to depict. Generally, artists depicted Jesus blessing of the bread to underline the connection to the Eucharist. Otherwise the figures tend to be pretty static and posed – John resting his sleeping head on Jesus as the “beloved apostle” was a standard convention in the scenes. Often Judas was singled out by putting him alone on the other side. But overall, a tidy row of figures.

The central passages of our two earlier examples.

Art develops its own conventions and shorthands for storytelling. This table arrangement is one where realism is sacrificed for clarity. Each apostle is clearly shown, Jesus is central, and Judas obviously distinguished by placement and profile pose – not face on.

Leonardo sticks to basic convention – synthesizing what came before – but unleashes shocking realism and higher idealism.

The arrangement of the figures in a row on one side of a long table with Jesus in the middle, Judas in profile, and perspective making the painting part of the room are all commonalities. Apparently Last Supper paintings were popular for convent refectories - they gave the impression of eating with Jesus and the Apostles.

The arrangement of the figures in a row on one side of a long table with Jesus in the middle, Judas in profile, and perspective making the painting part of the room are all commonalities. Apparently Last Supper paintings were popular for convent refectories - they gave the impression of eating with Jesus and the Apostles.

Both the other examples here are dining hall frescos. Here's the Castagno version from up above.

Note that the whole wall is painted, but the Last Supper is set in a little perspective box, while the Crucifixion scene is not. It is differentiated spatially. You are to understand it as physically adjacent in a way the other isn't.

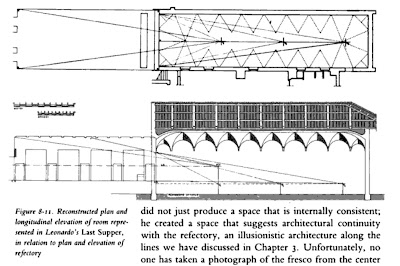

Leonardo takes up the whole wall of his refectory, but it’s easy to see that his painting fits the general terms of the type. Here it is in context.

Note that the perspective in the picture doesn't harmonize perfectly with the room. There's a disjunction. And the ceiling of the painting doesn't match the vaulted refectory.

Leonardo is showing visually that the scene is both connected to the present and apart.

It's the changes that art so important. Instead of the standard blessing of the bread, Leonardo shows the moment when Jesus announced one disciple will betray him. The bread is still prominent to keep the Eucharistic reference, now there is an element of psychology to bring the scene to life.

Remember Leonardo's interests in expression and anatomy. The new narrative moment let him design each figure as an individual – note how poses and expressions don’t repeat. Multiple opportunities to study outward signs of psychic impact. You can see it in the close-ups.

The old static set-up is replaced with psychic drama and movement so a frozen scene comes alive.

But note the psychological contrast between the reactions of the apostles and Jesus' mood. Calm, serene, resigned - Classical. He is clearly apart, even if you don't know a thing about symbolism, but differentiated in a way that is based of perfectly natural reactions.

But there is lots of symbolism as well. The dear apostle still swoons, but away from Jesus. We suspect is was to keep clear division between Jesus and the others.

This allows for a brilliant contrast between John - at peace in his faith - and Judas - the archetypal betrayer.

The moral distinction personified by John and Judas is shown by mirroring them. It's actually a triple contrast. Look at the forms and poses - John is the bright, fair positive reflection of Jesus and Judas the dark, ugly negative one. Jesus gestures towards the bread, John placidly accepts, and Judas reaches unworthily. Both are smaller than Jesus and reflect each other as inverses.

The color is where it gets really interesting...

This is fascinating, but don’t know it it’s intentional. The paint is in such bad shape anyhow.

But look - John is the less intense chromatic reflection of Jesus - paler blue and less fiery reddish hue. Judas keeps the blue to establish the connection between them then reverses the reds with the exact complement. This means they don't just contrast - their direct juxtaposition is hard to look at.

No need to put him artificially alone on the opposite side,

Now move to the larger arrangement. Leonardo keeps the apostles on one side of the table, but instead of an even row, they’re in balanced groups of three. This keeps the overall harmony and symmetry, but enhances the individuality and movement.

You can see where this is headed. First comes the greater instantaneity than the earlier versions. Greater temporal material realism to go with it. The whole thing just rings more true to the eye and mind. But there is a deeper structured order built around the simplest of ratios – threes and fours. The old Pythagorean harmonies with the connection to cosmology and music as well.

This paradoxically makes the simplified abstract substructure stronger and enhances the sense of real transience and temporality. The deeper order and the world of appearance both presented more effectively than before. Blowing the expressive range out on both ends and enhancing the overall unity between the further apart poles.

This paradoxically makes the simplified abstract substructure stronger and enhances the sense of real transience and temporality. The deeper order and the world of appearance both presented more effectively than before. Blowing the expressive range out on both ends and enhancing the overall unity between the further apart poles.

Look at the figural clusters. Each is individuated and planned as part of a group. The momentary and the harmonious. This mix of immediate realism and deep structure was planned on two levels.

Like the Mona Lisa you’re getting the momentary psychological realism and an inchoate feeling of profundity from the deep structural harmony.

To integrate this degree of planning on this many levels was beyond the standard workshop practices of the earlier Renaissance. This is why Leonardo's new approach to drawing seems as important as his painting techniques. Different kinds of drawings let him work out various details and their combinations. Doodles, drafts, studies, and concept drawings all rolled together. Even the different parts had stages of drawings.

Here are two preparatory sketches linked to the Last Supper from different planning stages. He struggles to visualize Jesus's face - not surprising for a reflective Christian with an awareness of metaphysical gradients. Here he's using chalk to model volume and texture with light and shade. The Judas face is a careful study of the anatomy in relief.

Leonardo, Head of Christ (study for The Last Supper?), around 1494, chalk and pencil on paper, Pinocateca di Brera, Milan,; drawing of Judas for The Last Supper, red chalk on paper, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for The Last Supper, between 1494 and 1495, red chalk on paper, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

One way to “idealize reality” is to integrate highly individualized figures into a structured, artificially perfect higher-order arrangement. It keeps the appearance of the instantaneous and subordinates it to the timeless. A world that reads as real but shines forth a more perfect logos than the chaotic material reality around us. And if more perfect orders ring luciferian alarm bells, remember that not all order is logos.

Leonardo doesn't claim to have the secret to creation. He doesn't profess to know the mind of God. He just tells you where to look.

Jesus again. The central anchor in the middle and not in any group. Serene expression – psychology – matched by stable triangular design – composition.

He’s the link that doesn’t move, infinitely patient and pointing up.

Jesus shows us how Leonardo layers meaning around a simple symbolic geometric shape. Formally, it reinforces the notion of Jesus as the stable anchor and teacher. The triangle is a wide-based stable shape that creates a psychic response in the viewer associated with upward-directed permanence. The trinitarian shape shows Jesus' divine nature without need for a halo. And the direction has you look up.

Emblem from the Lucas Jennis' Musaeum Hermeticum, Frankfurt, 1625, reprinted 1678 and 1749.

Note the contrast with the Hermetic inversion from an earlier post. It's the satanic idea that good and evil balance and the intrinsic impossibility that the human intellect is the arbiter to Truth.

Accept reality or succumb to vanity. It's always a choice. That's why you earn the consequences.

Reverse the force of the revelation flowing out from Jesus. The ordered chaos of the apostles' personalized reactions of the apostles flows into and through the timeless perfection implied in Jesus' triangular form, then into the mental leap – leap of faith – to the ultimate reality beyond.

So that’s Leonardo’s take on the Logos – the seen and unseen natures of the Incarnate God are conveyed through classical geometries and harmonious arrangements more than overt symbols.

And this extends to the setting. The strong perspectival arrangement of The Last Supper is another of it’s most striking features. Note how the vanishing point fixes on Jesus’ temple.

Leonardo wasn’t sold on the basic Albertian model of perspective as an illusory space box with figures inserted into it. For one thing, he correctly identified that it failed to simulate binocular conic visual fields. For another, it treated the space and figures as separate things when both should be part of the same painted concept.

The link introduces a painting known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa or the other Mona Lisa. The author is using Leonardo's perspective as a way to assess the authenticity of this portrait though the larger point stands. Let's look at the Ilseworth Mona Lisa for a moment - it seems like it could be important.

Leonardo (?) and workshop, Isleworth Mona Lisa, Early sixteenth-century, oil on canvas, Lisa Gherardini, private collection

Here is the evidence. It seems convincing enough though we can't really say from here. Would love to see them up close.

The close-up could be a younger, prettier Lisa. If Leonardo did take the more famous version around with him and kept working on it, it would deviate from the original face. Also if the workshop was on it, they are less likely to experiment and will paint the likeness.

But in the end, how do you tell?

Raphael, Portrait of a Woman, between 1505 and 1506, pen and ink wash over stylus, Louvre Museum

This drawing was made by Raphael shortly after coming to Florence and seeing the Mona Lisa. The link uses it as “proof” because of the columns in the Ilseworth painting and the Raphael - it implies that that was the painting he saw.

The thing that strikes us is how he picks up on the expressive shadows around the eye and mouth. That and the pose - Leonardo's main innovations.

We can put them all together and see for ourselves if anything jumps out. It's really impossible when you can't even see how the paint is applied.

We can’t tell. Let's get back to the perspective.

The advantage of painting over reality is that a scene can be idealized by imposing a higher conceptual unity on all of it – figures, space, themes, etc. His radical compositional idea of designing figures and space together was the reverse of the Albertian method. Rather than design the stage then populate it, Leonardo composed the figures then designed the space around them.

The advantage of painting over reality is that a scene can be idealized by imposing a higher conceptual unity on all of it – figures, space, themes, etc. His radical compositional idea of designing figures and space together was the reverse of the Albertian method. Rather than design the stage then populate it, Leonardo composed the figures then designed the space around them.

So for him to keep such a rigorous perspective frame, there must be a reason. What would perspective mean to Leonardo? Nothing less than the power of vision to organize reality. Which is basically our point - that his art is how he expresses his epochal nature.

His understanding of it was flawless – better inventors Brunelleschi and Alberti.

Leonardo, linear perspective study for the Adoration of the Magi, around 1481, silverpoint, pen, and bistre heightened with white on prepared ground, Uffizi, Florence

Perspective is a way to rationalize space according to the monocular logic of a viewing pyramid that simplifies optical geometries. It abstracts space. In Renaissance terms, it “idealizes” it by making it simpler.

The key to perspective illusion is the vanishing point. The converging lines meet there, making it the central organizing axis of the whole arrangement. This is a big difference between a perspective and real seeing – it’s arranged around a fixed point. So that when Jesus’ temple – the seat of his human mind – it at the vanishing point, it becomes metaphorical. Crossing between material resemblance and metaphysical symbolism.