Time for another How It Means post. These aren't a regular thing but an occasional look into how we make and communicate meanings. To support the regular things.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

The reality is that all our activities and exchanges are mediated through sign systems of some kind. This isn't the postmodern idiocy that signs "make" reality. But they do impose pathways on how we understand it. How Something Means posts are ways of working through basic meaning-making and communication issues without needing huge digressions in other topics.

The last How Something Means post looked at how pictures convey information. It built off the first one on words and identified some of the differences between these two basic ways of communication. These are very broad posts that lay out basic considerations to avoid the modern intellectual traps that led us into this epistemological dead end. Old friends like The Philosopher's Name and Textbook Learning. These are artifacts of modern educational bloat where unreadable "theory" - even blatantly self-contradictory nonsense - is transformed into short "summaries" and given Legitimacy! by attaching a name.

Here's a good example of a nonsense statement that a ton of 20th-century theory was built on. Anyone who's studied the humanities in the last oh 40 years heard some variation on this message.

The way summary learning is supposed to work is that

a. there is a historical record based on honest analysis

of primary factual evidence.

b. bodies of experts study a. out of an honest desire

to further human knowledge.

c. patterns are recognized that honestly reflect the

preponderance of b.

d. these are honestly summarized for mass consumption

with advice for further information.

The whole story may be too big, but at least the sketch reflects what is knowable as correct. Why? Note the key word. The Western concept of history requires a high-trust context. At the end of the day, the researcher has to be trusted to translate even the unfavorable document or avoid the sexy theory that contradicts reality.

This may be the sort of learning that appears in some textbooks. But it isn't Textbook Learning. Instead of starting with the best read on the facts, Textbook Learning starts with "theory". And since

that's meaningless screed, it can be distilled into whatever the narrative engineers want. It's double deception - the Philosopher's Names were themselves fraudulent cultural subversives.

This is an actual example - one we've mentioned in early postmodernism posts.

And what a conga it is.

Because the authorities aren't just epistemologically illegitimate, they're also factually wrong. In fact the derivation of the textbook aphorisms is actually inverted.

a. knowledge begins with theoretical models made

up by self-fluffing materialists

b. groups of NPCs make careers pulling things out

of context and forcing them into a.

c. there is no pattern other than everything proves b.

If it doesn't, down the memory hole.

d. the most egregious illustrations are chosen and

presented as "your history".

The narrative engineers cherry pick the most useful frauds for the current agenda. New generations of frauds build and repeat. And it's all constructed on the false assumptions and outright lies of secular transcendence. The collective fantasy that absolute timeless properties are present in finite, entropic reality and are fully knowable in themselves by subjective human minds. Direct material contradictions like wet dryness are more ontologically plausible.

Curiously official post-Enlightenment intellectual culture and luciferianism are based on it.

Shame about those pesky things like mortality and the laws of physics...

It is the logical endpoint to the collective pretense that feelings matter ontologically.

Abandonment of truth for for appetites, vanity, and avoidance of responsibility is why no meaningful insight has come out of a philosophy or criticism department since the mid-20th century at latest. Probably much sooner, but we're being conservative because the claim is not qualified. Not few meaningful insights. No meaningful insight. Obviously we aren't talking about a sharp observation about the use of metaphor in Dickins, social themes in Verdi, or finding an old document. A lot of facts have been accumulated and cataloged.

We mean a philosophy, critical or social theory, or social science revelation that transformed the West for the better. Not one.

The West would literally be better off had university humanities never been invented.

How things mean posts work out basic practical details. Just asking if the method of knowledge production is actually capable of the claims being made has blown open so many lies and misconceptions so easily. It's like no one bothered to ask.

Nuno Andre, Formula One Mesh, 2019

The posts reverse Textbook Learning with the sort of fact-based logical breakdowns that textbooks ought to have. And they replace Philosopher's Names with logical observations of the historical record.

When a name does appear it's to credit an idea that is truthful. Not authorize something that isn't.

How pictures mean built off from how words mean to work through the relation between visual and linguistic representation. The problem is that "visual" covers a lot of ground. Looking at the world out the window transmits information visually. So do the countless types of man-made images surrounding us. And while the general process is the same, the details are different for all of them. So this post isn't so much thinking about a new form of meaning-making as much as a subcategory of the last one that looks at paintings in particular.

This makes sense considering how much the Band has been thinking about the art of the West from different angles lately. We've clarified a lot for ourselves and think it worthwhile to lay it out in one place as a reference.

Sanford Gifford, A Gorge in the Mountains (Kauterskill Clove), 1862, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

But before that, they spend several centuries developing into an incredibly complex visual language.

The art of the West is a pinnacle human cultural achievement that's too versatile and expressive to sum up. The way satanic globalists separated it from its culture then inverted it seems too fluid over too long to be human. But we can bring it back - one person at a time if need be. Not for nostalgia, for the future to build from.

The thing about paintings is that unlike the natural world, they are completely man-made creations. Unlike a photo, they aren't even based in something that really exists. Painters are inspired by the world, but are free to interpret it how they want. In a way, this makes them the perfect example of the kind of representation we looked at in the how pictures mean post - something taken up as if natural, but as artificial as a sentence in construction.

This post will take one picture and use it as an example of how we break down the symbolism and syntax in the way we do for the blog. It is important to remember that this description is more step-by-step then it is in reality. Pictures deliver information in less sequential ways - noticing things simultaneously connects them in your mind in a way that we can't duplicate in a written sequence. As always, we are artificiall systematizing for clarity's sake.

Here's the picture.

Joseph Höger, Chapel in the Woods, 1850, oil on panel

There's not much information on it. Here's the page the Wikimedia Commons links to. Höger was Austrian, and he wrote the date on it when he signed it. It's probably in a private collection because there's nothing coming up on an internet search other than auction results. So we can look at it without being influenced by third parties. We have to, because there's nothing else.

The first thing to look for is what it's a picture of. Start with a simple identification of the things depicted. The title can help, but don't overrely on it - many titles aren't even original. Realistic depictions convey information by resemblance, so you need to trust your sight over others' words.

TYPOE, Confetti Death, installation, 2011

Contemporary art is good when it conveys... truth. Quelle suprise. Is there a better image of the modern art world than a symbol of death spewing a blast of colored plastic trash on a museum wall?

Cultural inversion takes time - the globalist monsters that inverted and destroyed the institutional arts of the West didn't do it overnight. It's why the butcher's bill for Modernism and its aftermaths is so vast. An act of attempted cultural genocide that only failed insofar as it did for lack of universal reach. And succeeded in that the cost to our institutions, communities, nations, souls is incalculable. How much creativity, beauty, and sheer human spirit did the perverse monstrosities of modern culture cost the world?

Clyde Aspevig, The Joy of Winter, 2014, oil on canvas, private

There are fine contemporary artists. We're talking about the complete abandonment of their cultural missions by virtually all cultural institutions.

Real art has continued organically and mainly without support other than clients. It survived in spite of countless billions earmarked for it's satanic inverse. This is the story that needs to be written and lights the future.

The Band had locked in on art because of how much distortion and outright lying has surrounded it. The sheer degree of beast system malevolence and wizardry indicates the importance. Art is how a culture expresses itself to itself and others, now and in the future. It freezes episteme at a moment in time and passes it forward for others to see. You can find inspiration and connection in what your ancestors saw. Common cause across generations. Common values, joys, tragedies, and dreams. And it's inspiring. The rhetoric is powerful.

August Wilhelm Leu, Norwegian Fjord Landscape, 19th century, oil on canvas, private

We needn't explain why emotionally-charged blasts of visceral, intergenerational truth is problematic for the gray goo fantasies of globalist beast dancers.

The value of How Paintings Mean comes through when you consider the effort spent to keep you from even considering... something that has been at the center of human cultural activity since there were humans.

It's a two-step dance.

Ellyevans679, Danse Macabre:-Dance of Death

Step one is that sociopathic shills infiltrate, corrupt, then destroy the culture institutions. Much like Lord Foul infiltrating, subverting, then overthrowing the Old Lords in our Thomas Covenant posts.

And in both cases,

the institutions were set up to

fail by their terms of creation.

Centralizing "Western culture" or "official" culture - as something external to pop culture - in institutions funded with globalist lucre or statist appropriation was doomed from the start. We've seen in countless posts how the elites were hostile to national culture since before the European nations formed. This accelerates with the development of a global financial elite class. Turning a Rockefeller bequest to naked dyscivic evil is a nudge, not a stretch.

The secular transcendent lie behind all of it is a usual suspect - that the Enlightenment ushered in a new reality of official commitment to truth and reason. In the Land, the Lords' have their own "enlightened" secular transcendence. Their belief that they can make a fallen world a paradise - is a vanity that leaves them vulnerable to their world's Satan.

Sometimes it's brutally obvious.

But here's a better example of how central control jacked the American arts. [Note the skin-crawling irony of years of Eurotrash globalist posturing about the "boorishness" and "lack of sophistication" in American culture. All while perpetuating a cultural crime against humanity the magnitude of which is beyond calculation. Butcher's bill is vastly too gentle.]

Came across a link that connects to the early posts on architecture and Modernism - especially Harvard's role in it. Consider how incestuous this is, and then how influential Harvard has been on American and world arts and culture. See the problem with centralization?

Walter Gropius, Graduate Center, 1948-1950, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Click for Infogalactic on the building. And yes, the pooh-bah of Modern architecture was really called "Gropius".

The Graduate Center was an early experiment in multi-use postwar university planning. Gropius was the father of the Bauhaus, International Style modernism, and Harvard's own design and architecture school. America was entering the 50s boom, and the guardians of culture were transforming historic campuses into...

The Graduate Center on completion in 1950

The article calls it "extending the sweep of the Harvard Law campus". That's the Enlightenment-flavored Neoclassism in the background.

Here's the centralized incestuousness. The client was Harvard Law School. The architect was the founder and professor at Harvard's School of Design. The related art exhibit was held at the Harvard Art Museums. The curator of the show was the "Stefan Engelhorn Curatorial Fellow in [Harvard's] Busch-Reisinger Museum". The expert opinion was provided by Harvard's "Graduate School of Design Professor in Practice of Urban Design" - same school as Gropius. Yet this is all good because Harvard is committed to Truth! and Excellence! in all things. It's in the motto.

About that art...

Richard Lippold, World Tree, metal sculpture, 1950,

The Bauhaus "aesthetic" involved placing odd lumps of matter in random places in the buildings. Words are then mouthed - like integrate, art, and architecture - that make little sense in the context. It's vertically-integrated atavism. Modernism is based on replacing the arts of the West with its satanic inversion - Art!

The odd lumps were exclusively provided by "names" from Europe with Lippold the one token American allowed to contribute. This clothes rack/aerial might still be there.

To break a culture, the language around it has to be reprogrammed. This is where centralization and fake prestige come in. When someone hears "integrating the arts" they think of an beautiful environment - the last thing the beast wants coming to mind. Enter Harvard - now the "world's greatest university" declares weird lumps of Eurotrash in a cheap-looking penal colony to be "integrating the arts".

The person who looks to Harvard for cultural leadership and the arts for beauty can't have both. Best just watch t.v. Where the message will translate the Harvard one into idiot-speak while perpetuating the nonsense world where "Harvard" connotes truth.

Josef Albers, America, brick relief, 1950

The article says students don't realize that this is Art! This is supposedly "part of the Bauhaus approach". You are surrounded in Art! subconsciously. And may not "recognize the genius" that transformed a simple building material into a "masterpiece of negative space".

The connection between the words and the things is shattered

Hans Arp, Constellations II, 1950, Harvard Art Museums

Globalists are satanic. Rubbing your face in the degradation of your culture adds pleasure. The article says Arp's "mural" was stained “American redwood,” in the Bauhaus aesthetic of "referencing local—or at least native—material".

Or as Donaldson wrote "how do you hurt a man who's lost everything? Give him back something broken".

Here are a couple of the major spells used to separate you from your cultural, intellectual, and spiritual patrimony.

#1 Art is beyond you.

Freaks like Gropius took hold under a fog of obfuscatory theoretical bullshit and self-proclaimed cultural authority. This enabled people who rightfully objected to the this invasive cultural crime to be silenced as philistines. While the anointed servants of the beast danced, capered, and jeered in their expensive eyeware. The Band's animus for our "cultural inasititions" comes from the enormity of the atrocity they committed against the very thing they were tasked to serve.

Hence the "Long March through the Institutions". These still have a certain kind of prestige, class status, and zombie corpse of intellectual credibility. The common person has been conditioned to think or fear that they don't "understand". Demons and freaks depend on being able to outgroup the reality-facing in their little institutional fifedoms.

Like all globalist perversions, it's funded because it's unpopular.

The derision compounds. The wicked hate and debase your culture, then mock you as a barbarian or rube for not genuflecting to the debasement. At which point, they've failed their moral test but yours is just getting started...

#2 Critics judge quality

No they don't. The system is tautological. The critic is important because of their institutional status. The status comes from the reputation of the staff. But it's all self-declared. If you cannot read and resolve the following question and still somehow see these zombie institutional husks as "prestigious" or "authoritative, go away. You're part of the problem.

How can a body that puts Gropius at the head of anything be considered to have anything to say about art or culture at all?

Seriously. An underrated test is to simply ask how you would react in the same situation. Any mentally stable person would have said to take your thousand... [yard] stare and crappy glass birdcage and get lost.

#3 Art is shocking, transgressive, critical

One of the most toxic of modern lies - the myth of the avant garde. That Art! should be constantly attacking its culture instead of expressing it. This dovetails with the Marxist lies about perpetual revolution. It's the ethos of the pathogen or the sadist - existence as an endless process of ugliness and destruction in the name of something that can't exist. That is, no reason at all beyond a hatred for the glory of Creation.

Consider this bit of slickly packed excrement from usual beast pipers the BBC, PBS, and Time-Life. Hughes was once described as "the most famous art critic in the world" - partly because of The Shock of the New, his 1980 book and television series on modern art. According to one shill, "this legendary book has been universally hailed as the best, the most readable and the most provocative account of modern art ever written". K.

The success of this offal points to more incestuousness - he was TIME magazine's longtime art critic at a time when it was the beast's piper for the more "serious" wing of the popular mainstream. This may shock younger readers, but in the before times, big media would brand platforms as having an ideological "position" and the sheep would queue up behind the appropriate illusionist. On the one hand, it beat thinking. On the other, it won't shock them to know that all the illusions were globalist and all the Pipers Pied.

It's vertically integrated - like the Graduate Center, only in media and criticism. Time-Life leverages its massive control of the public discourse at the time to transform an inhuman shill into a critical celebrity. Then other beast platforms leverage the celebrity into a cultural plague bacillus. And the masses consume because he's famous. And the production quality is high or something. And note the platforms. TIME was "substantive" without being snooty. But public broadcasting... Younger readers who have had the misfortune of landing on NPR by accident my really find it hard to believe that for a long time a particular stripe of sightless egomaniacs considered "public" broadcasting more "intelligent".

In the beast system, reality is irrelevant. It's the illusion that matters. And here we have a gold-plated pop intellectual pedigree to sell the lie that art opposes culture!

Lucian Freud, Large Interior W11 (after Watteau), 1981-1983, private

Consider, Hughes was a champion of Lucien Freud, grandson of the demented "therapist" and 20th-century British Art! darling. His soulless ugliness lacks techne or episteme and is a perfect background for the inverted depravity of the modern beast system.

This description is more inverted language. The words don't reference what is shown. His obsession with genitals as an accomplishment

Antoine Watteau, The Feast of Love, 1718-1719, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

And here's Watteau. An early Rococo painter who the Band thinks is overrated but is the Platonic form of art next to Fraud.

We were jokingly planning on calling it a litmus test for psycho-spiritual health when we realized it really is. Some people really do like these smears - to a degree that is more than brainwashing...

Remember - art expresses culture. So to a hollow NPC flickering in the lurid glow of the beast, something like this really does speak to them. It's an expression of the de-moralized, walking death that is their modern materialist existence. For them, the logos streaming from the art of the West would be like staring into the sun.

#4 Art is considered unmanly.

The equally fake inverse of the avant-garde rebel. This is because of how it is presented and who presents it. Aristocratic fops and modern servants of the lie - this historical art class - never had much interest in robust societies. Virtue of any kind for that matter.

There is also the pernicious lie that men are emotionless. They aren't incontenant, but the depths of their passions are unsurpassed. And art expresses culture on the deepest emotional level. It has trafficked in profound and often manly feelings from the start. There is no reason why the most stoic man don't feel quietly braced by a well-crafted reminder of the power of his heritage and divine image. Alternatively, the man who rejects the health of his culture is a parasite.

Sanford Robinson Gifford, The Artist Sketching at Mount Desert, Maine, 1865, oil on canvas, private

Physical exertion, technical skill, inspired vision, and natural beauty. What's not to like?

We propose an alternative path. Abjure the wicked, spit on satanic lies, and lock eyes on the good, the beautiful, and the true. And recognize that the scorn of the damned is a badge of honor. The Band has no desire to compel anyone. We want to free people from artificial compulsion to align with reality. But if there is one thing that we would make an exception for, it would be this - when it comes to artworks, trust your own eyes. Learning to look is an excellent way to develop discernment.

And leave the demons to their halls of the dead.

|

Jiayun Xin, Land of the Dead, digital art, |

That's a rough outline of the issues and the motivation for the How it Means posts and this subject in particular. Because if we are moving past the false claims of the beast-dancers, it isn't enough to point out that art was corrupted and inverted. That's easy. It's also the path to despair. Because when you look at the vast scale of Art! - all the institutions, venues, schools, collectors, writers, etc. - and how long it's gone on, it can feel hopeless.

It isn't. Quite the opposite...

Demon-Works, Carousel of Madness

That entire monstrous, clanking, wheezing apparatus is a sham. An inversion called Art! imposed on a vast and complex cultural patrimony called the art of the West.

Hopeless?

You don't even have

to get on board.

You can join us as we look back at what real artists were really doing by looking at paintings. Real works of art that continued to wed techne and logos to reflect on reality in some way. It doesn't matter how old or vast the world of Art! is when you can just walk on by and let the whole demonic carousel sink into the abyss.

But this means you have to know how to look. Back to Höger.

Start with the subject. What is it a picture of?

This one is easy - there is a chapel in the wood as the title suggests. There's a road and stream that come in on converging diagonals and a person with a dog just below the point where they meet. Across the road from them is a sign or marker - likely an indicator of the importance of the chapel.

Pictures communicate by showing, so take time to look closely. There's usually an overall impression, but there will be lots of details that are easily missed. Just carefully describing what is there - even if it seems tedious - is a good way to make sure you get everything. Like doing a close reading when analyzing a poem.

Joseph Noel Paton, Dante Meditating the Episode of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, 19th century, oil on canvas, Bury Art Museum

Paintings and poems were often compared in the past, so it isn't surprising that both pack a lot into the details.

We have to account for the differences in how they do that.

A poem is written in a language, so there is a sequence that the words follow. Anyone reading who wants to understand will read in order. Perhaps going back as needed, but the overall comprehension of the poem is as a string of words. Paintings can accentuate things, but can't compel you to look with the same structured order as a sentence. Pieces still need to be assembled to make meaning - like the words of a poem. But the nature of the pieces are different so they have to be assembled differently.

In pictures, spatial relations - real and illusory - correlate to symbolic ones.

We tend to think of compositional arrangements as aesthetic - arranging things relative to each other to create a pleasing effect. Like the arrangement of notes in a musical composition. But an artist can - and often does - use the relation part of relative like a kind of syntax. So that the meanings of the individual pieces come together to form visual "statements".

In the Paton painting, architecture makes a division between a "real" foreground and and the dream background.

Remember - it's all a picture. But it is arranged so we perceive the illusion of depth. We now have three dimensions of spatial coordinates. The Cartesian plane of the surface and the appearance of a z-axis into depth.

Everything on our side of the architecture is real. Physical closeness = materiality here.

But note how on the x-y plane, the whole center is left open. Dante is closer, but you are being directed further in by the composition.

"Behind" the architecture is the content of Dante's dream. The further back you, the less concretely real, so the background is the dreamscape.

But the subjects of the dream - damned lovers Piero and Francesca, whose love was so strong they found each other in Hell! - occupy the middle of the x-y plane. Note how they are also depicted as less solid and colored than Dante or even the real-world architecture below them, but are most prominently placed at the center of things.

Put it together and you are given a clear depiction of Dante and his dream in a way that make the relationships between each other and with you clear.

Dante isn't just a dreamer, but a writer, so the content of his imagination is the precursor to his poem. Paolo and Francesca seem to emerge from the space between his mind and his book and project forward into time and space. His creations as well as his dream.

Then there's his placement. Sitting next to the arch, the dreamer is also the gatekeeper to a world of poetic imagination.

An important effect of the lack of sequence in a painting is that it's easy to layer meanings. There's narrative, symbolism, ontology, all in a simple picture. Plus however many other connotations. Once you see how paintings combine and arrange symbolic elements into more complex "statements", real art - art that expresses logos - gets way easier to appreciate.

What are the spatial parameters in the Höger?

It's a landscape, so there is an impression of 3D depth. Not a firm perspective like a Renaissance painting but a rational opening into misty distance. And every painting has a Cartesian plane as a surface. So the Höger can operate through different kinds of relative placement at once.

It is important to remember that different types of things can be placed in this matrix - not just representations of object relations. Because each symbolic element in a picture is expressing differnt overlapping meanings. If you think of semiotic systems as a continuum of precision, pictures are like the opposite of numbers.

Take this allegory from a late academic master as one of limitless examples.

The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ, about 1852–1854, oil on canvas, Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The entire structure of Empire emanates from Augustus, enthroned before a temple and crowned by virtues. His court surrounds him, then his priests, his legions, and the representatives of the peoples of the empire. All before a vast, Colosseum-like sweep. But he's remote - the focus of the compositional arrangement, but not our attention. The immediate subject is the Nativity - here announced by an angel.

It always seemed Providential that Jesus was born during the Augustan peace that began the Pax Romana. This allowed the Gospel message to spread quickly across a large swath of ancient world.

Given our emphasis on Logos, it's also worth pointing out that this was a time and place where the philosophical language was sufficiently developed to even express what Jesus is metaphysically. No one else even had an equivalent word to "logos". We don't.

From this perspective, the whole classical sweep is a protective shell that brought God into the world and spread His message.

But think how much else is contained here.

What we breezily sum up as a "classical sweep" is a complex historical tapestry. With references to the sociologies, politics, religion, and military of ancient Rome. Historians might be interested in provincial costume, priestly orders, Legion standards, who the court advisors are, engineering and architecture, etc.

This makes it impossible to settle on one definitive meaning. We can identify a primary one, but there is always some sort of reference to something secondary - even just a hairdo or type of jacket.

Compared to words, mathematical statements and sentences have a precise lack of ambiguity that reaches abstract perfection. Pictures are webs of associations and connotations, shifting in and out of relation with each other, chaining allusions across knowledge domains, and always seeming incomplete. It's something we have to come to grips with when reading paintings.

It's easy to come up with a pro- and anti-Roman interpretation of this picture. Augustus creates positive conditions for the spread of Christianity, but his self-deifying Imperial cult violently opposes it on religious grounds. It's complicated, like the reality a painting depicts.

There's an autistic desire for closure that plagues modern society. It's the deluded just-so fables of the boomers, the textbook learning of schools, and the paper-thin communication venues of the youth. It's especially prevalent in a contemporary pathology known as "fact checking" - a form of reverse-IQ test where a moron asks a liar a question online. Typical beast system manipulation of declining national intelligence and critical thinking.

The deeper problem is the insect-level assumption that reality has single explanations. Beyond whether the online liar is honest - how lost does one have to seek one word answers to socio-political scenarios?

Paintings resist closure. The point is to show a vision of reality that you can extrapolate into your own life.

Note how the symbolic elements with all their associations are organized according to rational spatial relations. Even though there is no possible way to imagine this as an actual scene happening, everything is arranged as if they are physically present in real location. The spatial relations are the "syntax" that form the individual parts into a more complex message. It's how we can identify what the primary theme is out of the different possible associations of each piece.

This means that the composition is communicating on two levels at once

1. a realistic depiction of object relations in a physical space

and

2. the syntactical arrangement for a symbolic message.

Take a closer look with Höger -

1. Illusory

Zooming in on the central elements, we see that the chapel looks as if it's physically behind the figure. It appears optically realistic. If we think in terms of a possible narrative, the path establishes the chapel as someplace the figure may be going to or coming from.

We call this illusory because the arrangement of elements fools the eye into seeing a real setting with activities that we can recognize. We therefore process it as if it were a glimpse of a real place.

2. Diagrammic

The chapel is dead center in the picture, with all the prominent diagonals converging on it like a vanishing point. This is arbitrary and establishes the importance of the chapel in the message. The figure is directly below, so that the illusory move "back" into space is also a vertical sequence from person to chapel to heaven beyond. A spiritual progress superimposed onto a narrative one.

We call this diagrammatic because the arrangements create meanings outside of narrative or illusory realism. Like a diagram.

In real life, the distinction is way less cut and dried then we make it seem here. You just need clarity to start to see how to break down the different pieces and their interactions. In reality, the fluid nature of pictorial meaning allows for the literal and figurative to flow back and forth and pile up in layers. It's not just embrace the power of and, it's that and is the key to the whole thing. Leaps and juxtapositions - the way meanings layer in reality - are the whole point of pictures. It's also why we are drawn to them. Readers know that the Band loves leaks, juxtapositions, polyvalent patterns. We hope you do to.

Start with the space.

The chapel is clearly in the center and the dominant diagonals accentuate that. A landscape won't have the sharp lines of an architectural rendering but the perspectival recession is clear. The rough edges of the natural world seem realistic, but the view is highly structured around the chapel.

In an illusory sense, this creates a perspectival geometry that creates the impression of space.

Compare this arrangement to one from Russian landscape genius Ivan Shishkin - a good illustration because he has a similar rough textured realistic style to Höger.

Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin, Birch Grove, 1871, oil on canvas, private

Here Shishkin is creating a sense of depth, but it isn't so centered. It pulls you in on an angle to one side along the river.

You don't get the same central focus baked into the arrangement when the opening is skewed like this. The experience is more one of the overall unity of the landscape. And how good he is as a painter.

That's one of the difficult things about pictorial syntax. There is no one standard way of organizing things. Here's Shishkin with three different variations on an opening into a wooded landscape. Light plays an important role as well.

Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin, Birch Grove, 1875; Twilight, 19th century; Backwoods, 1872

A relatively sparse grove with an open middle, a winding road into a dense twilit pine forest, and a telescoping pull of light through the foliage are all different experiences.

And you don't even need a clear opening...

Ivan Shishkin, Meadow with Pine Trees, 19th century; Brook in a Forest, 1880

Two variations on a screen of trees with different treatments of light and space behind them.

You never need an excuse for Shishkin, but in this case, you can see how he shows us Höger-type forest scenes can be configured any number of ways. This means that the way that the artist does it is not the "grammar" of convention. It's a choice - for a centrally focused arrangement that pulls attention to the middle. Bringing us to the second level.

In a more diagrammatic sense, a geometrically-ordered composition is visualizing higher principles of order in the world. Geometry is based on perfect mathematical relationships - a way to represent absolute perfections that only physically exist in an imperfect material reality in theory. In writing, higher-level truths are expressed with logic, but paintings are visual and can show geometric expressions of order.

Höger gives us the impression of an entropic, irregular natural world, because that's how it looks. But he also uses geometry to show the immaterial logos behind that appearance.

A stable triangular base creates a feeling - and a foundation - of stability and timelessness

It's not a new concept.

So we are given a sort of double vision - a world of impermanence and change realizing a logos that does not.

Since the arrangement with a central focus is a choice, be attentive to what Höger puts there. It is something that the whole painting is organized to highlight. A composition where the timeless and material appear at once. Kind of like what a church symbolizes...

See the parallel? The composition shows a higher truth - logos - in the created world with geometry.

That logos-geometry points at a chapel - a type of building defined by Logos in the world. Christianity is based on the miraculous union of ultimate and material reality in Jesus that makes salvation possible.

There's actually a three-part connection here - between the person, the shrine opposite them, and the chapel. Hard to say more now, except that they relate.

Summarize - a stable, timeless, logos-filled vision of nature that centers our attention on a church with a figure below. Italics because below is referring to object relations on the cartesian surface plane of the painting and not the illusory depth. That would be "behind". Remember - pictures are diagrammatic as well as illusory.

Look at the cartesian field.

He isn't really following the Rule of Thirds because his central foci are in the middle of the canvas. But you can see that the shrine and the strongest vertical axes of the central trees do fall along the thirds. Even vertically to an extent.

This is an aesthetic norm that has to do with the organization of shapes and colors on a surface and not depth or subject matter. It aesthetic, not realistic.

This means it's something else that is there by choice.

Here's a detail of the verticals. They frame the central focus and add to the sense of timeless structure...

...with the basic temple front configuration.

...that always means timeless stability.

We also need to consider the vertical divisions. They also add to the sense of permanence - a grid in landscape mode exudes stability. But there is a different set of symbolic associations that come with vertical arrangements. Think ontological hierarchy...

Here are the basic vertical divisions with the chapel still highlighted in the center. They do seem to correspond to three zones in the painting - the lower ground and person, the middle horizon and chapel, and the upper treetops and sky.

There is a very old diagram here...

The stable encoded logos in the world ultimately points towards eschatological things.

Are we just making this up? If we are, the rest of the elements won't correspond.

If we're not just making it up, we now have a conceptual relations mapping onto to cartesian ones. A visual syntax that lets the parts of the painting cohere into a message

Consider...

The figure who is closest to us illusorily occupies the middle of the lowest level. She is near the apex of the base triangle so there is an implied direction even though she is sitting. That movement is up or back, diagrammatically or illusorily.

That aims us at the church - center of the illusion and the intermediate level.

Now we have a vertical progression - the church and the intermediate level bridge heaven and earth symbolically and earth and sky optically.

Diagrammatically we go from worldly life, via the church, to the heavens beyond. Except all we see are trees...

Exactly.

We can't see heaven. We are limited to the material - the natural human world of experience and things that have symbolic value as pointers to that unseeable higher place. Like a chapel. Now, you want to see how subtle the messaging is? We can't see God, but we see evidence in the beauty of Creation. One might say, heaven was behind the treetops. Metaphorically speaking.

It's like a pathway.

The source of Truth is not visible to us, but logic leads to it. It has to. It comes from it.

One thing to remember about the diagrammatic and the illusory is that they coexist. This is where the syntax analogy breaks down some.

A sentence has an order. There can be different levels of meaning but they all unfold as the text does in sequence. Pictures are way less constrained. The artist can put things however they want. So it's not just multiple levels of meaning in one string. There can be multiple strings overlapping, making connections between different meaning clusters at once. It's why art people love the word "juxtapose" so much. Juxtaposing things is what paintings do.

The illusion carries you back and in. This makes the message seem "natural".

The diagram shows the pathway of the Logos that nature hints at and the church connects with. Material and metaphysical logos bound together in one visually pleasing package.

How is this not cool?

Now it's time to think about the light.

It looks to be coming in from the top left, behind the trees - illusorily anyhow.

We can't see it directly - which is appropriate in a symbolic way. But it lights the chapel against the darker foreground as well as the path leading from the shadows to its door. The figure sits on the border. A symbolic choice? Perhaps - pictures are allusive and suggestive when the symbolism isn't clear.

Then there's the shrine - or whatever the panel on the post is. Most likely an image of some local significance connected to the chapel. The problem is that even when we blow it up, we can't make out what it depicts. But we can offer some ideas from what we've observed.

It occupies a mid-point between the figure and the church and bridges the lower and middle levels of the vertical arrangement. And it's blending with the natural world but capturing some light. Everything about it seems in-between. It would make sense from this that is is some kind of sign of local piety. Where the universal Christian image of the church meets the localized expression. Looking closer, the light seems to point out things that cross lines - like the person who chooses paths.

Don't get bogged down in did the artist put it there at this point. There's no way to tell past obvious subjects. Look at what is there. Nothing is by mistake. If the object that drips with in-betweenness is right on top of a division between light and shadow, it's significant. It's like the figure - just a little closer to the chapel. Illusorily and diagrammatically.

If the figure is applicable to the personal and the church to the transition to the metaphysical, then the shrine is applicable to the space between. Illusorily and diagrammatically. The local application of the universality of Christian truth.

So there's a logos structure that shines through the arrangement into the beauty of the material world. It brings the human, natural, abstract, and divine together into harmony. The logic of geometry lets you see how faith expressed through the forms of local culture connect to God. If the whole thing is easy on the eye, it's because it is. Everything is as it should be, without imposing on the variety of forms that make up natural beauty.

Of course this is just a general structure. A rough equivalence to a syntax. It explains why the picture appeals aesthetically and conceptually - at the highest level, Beauty and Truth are the same. This is different from specific content. We'll end with the difference between the two.

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, Classical Landscape with Figures and Sculpture, 1788, oil on canvas

It is necessary to strike a balance between the imposed order and natural variety or else this particular logos-in-the-world configuration becomes something else. Classical landscape turned it into a formula that stressed logos but lost natural variety.

The monotonous repetition that always comes with centralization is inhuman. We are imperfect material replicas of an immaterial divine form. Variety and imperfection within ideal parameters is our reality. Whenever we shift the abstract logic of the machine from a tool to a model of living we suffer.

Jean-Frederic-Bazille, Aigues-Mortes, 1867, oil on canvas, private

Classical landscape is a road to abstraction. The next step is to start thinking of the natural world consciously as a collection of abstract patches or forms rather than an illusion of reality.

Remember - putting medium over representation is one of the ways Modernism neutered artistic communication.

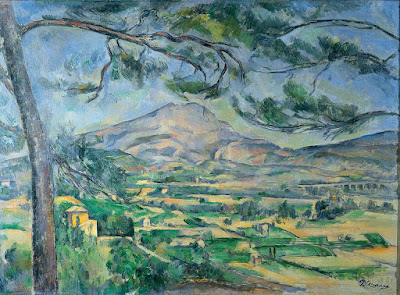

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, around 1887, oil on canvas, Courtauld Institute of Art, London

The official narrative credits Cezanne with recognizing that the arrangement of abstract patches subjective and that there is no objective beauty to share.

Albert Gleizes, Le Chemin, Paysage à Meudon, 1911, oil on canvas, private

This opens the way to all the geometric atrocities to follow - like the figurative slashing the face of Creation that is Cubism. Gleizes' insistence on "inventing" is the cultural equivalent of touting yourself as having founded a rape camp. You'd also attract lots of willing supporters.

Gregor Perušek, Flood in Ohio Valley, 1937, oil on canvas, private collection

And the modern hellcityscapes where the human environment is reduced to that grimy mechanical logic of the machine.

Arshile Gorky, Cornfield of Health II, 1944, oil on canvas, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

And all the other "subjective" affronts, piled up like shovelfuls of dirt on a new grave.

Too much structure is the soulless inhumanity of the machine. Material operation with nothing more. But too little structure and the landscape dissolves into subjectivity then chaos. The ultimate satanic dream of the dissolution of Creation. It's as if Aristotle was right about coming up that middle all along. Where order and creativity combine in full realization of human potential and open the path to logos through beauty.

That's form. The content level is way more specific and can't really be summed up the same way.

There's all the basic information contained in the depiction. The place - is it a real chapel? An actual crossroads? And all the secondary facts about clothing, flora, society, etc. that get included unintentionally. There's a lot when you think about it.

Then there are the things that are clearly part of the message. In many cases there is an obvious subject or symbols. Any painting of a scene or story will fall into this category.

Carl Bloch, The Holy Night, 19th century, oil on canvas

Religious art is either of an iconic figure or a story - often both. Tt doesn't do much good to foster devotion if you don't know what the subject matter is.

John Collier, For King and Country, 204.5 x 152.4 cm, oil on canvas, Chiswick Town Hall, London

As do paintings of events and people from real life...

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888, oil on canvas, Tate Britain

...or from literature, folklore, mythology, or other fictional source.

Any identifiable story of subject.

It can even apply to other modes if we know what the subject is or who the characters are. Like a landscape or seascape.

Ivan Aivazovsky, The Birth of Aphrodite, 1887, oil on canvas, private

Iconography is a traditional way of making pictorial content legible. Standardized symbolism for iconic figures and events from religion, culture, myth, etc. A bit like superhero costumes. The main difference between iconography and identifying symbols isn't clear. Iconography seems to have more of a tie to art and/or humanistic study, but we all know not to put too much weight on seems.

Trapani Crucifix from Sicily, late 17th century, coral Christ, titulus and skull on blue glass and silver-gilt mounted cross, private; Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Liberty Lights the World, 1878, bronze, private; Lawrence Macdonald, Venus, 1857, marble, private

Albert Thomas, Allegory of Dance; Allegory of Music, 19th century, oil on canvas, private

Less standardized personifications and allegories also fit if you can decode who the figures are. Here are two where landscape structures are used to convey figurative messages about the arts.

You can even reference older pictures and bring iconographies into the present. Like a British artist with a spin on a theme from Titian.

Titian, Sacred and Profane Love, 1514, oil on canvas, Borghese Museum, Rome

John Collier, Sacred and Profane Love, 1919, oil on canvas, Northampton Museum and Art Gallery

Collier adds a reflected figure looking at the two personifications to accentuate the theme of moral choice. It's more or less in the place you would be, so the idea of reflexivity extends beyond literal mirroring.

If you don't know the iconography you won't get the meaning.

It's easy to see from a few examples that the possibilities of content are endless. This really isn't different from the meanings of words and sentences though. And no one attempts to give you the meaning of all texts. They show grammar, syntax, usage, vocabulary. Once you have those, the combinations are endless.

For this reason, the variety of pictorial content is also less of a problem when we understand how paintings structure their meanings. There's more flexibility than a sentence and the combinatory rules are more case specific. But the arts of the West express truths, so the syntax will reveal itself on examination. Often on first glance. Then the specifics - subjects, symbols, iconographies, etc. with all their references and associations - fit into the framework and individuate the message. It's open and constrained at the same time. Like human existence is intended to be.

Now try this one...

|

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Trautschold, Shrine in a Forest Clearing, 1868, oil on canvas, private |

No comments:

Post a Comment