introduction and overview of the point of this blog.

The last few posts have dealt with epistemology and ontology in order to uncover the incoherence and deception at the heart of Postmodern philosophy, science, and faith. Once we establish clear, if general, categories, the lies and distortions of Postmodernism become obvious, and its sinister dyscivic, power-seeking agenda exposed. It is a perversion of viable processes of building knowledge, and next to the necessity and the limits of empiricism, the logic of causality, and the sphere of knowing that properly belongs to faith, it literally makes no sense.

Fortunio Liceti, De monstrorum caussis, natura, et differentiis libri duo…, 1634, engraved title page

Pre-modern monsters were generally conceived as distortions, perversions, and/or amalgamations of natural creatures. By rejecting empiricism, Postmodernism twists faith into a monstrous parody of epistemology.

The epistemological failure of Postmodernism makes it impossible for it to come up with anything resembling a coherent ontology. Without the ability to construct legitimate knowledge, its downstream deductions are invariably wrong with no capacity to learn empirically from those errors. This blog began by looking one such whopper - the idiocy of asserting discursively that discourse is meaningless - before pointing out that whoever controls the discourse controls reality. It is not a coincidence that the left targeted the knowledge and culture industries so aggressively. How better to pass off monstrous fictions as knowledge?

Marxist riot at Berkeley, the purported home of "free speech" in Boomer mythology. The lack of institutional response suggests that the abrogation of their stated intellectual mission is intentional.

The problem emerged when the word modern morphed into Modernism, a period of rapid cultural change beginning in the nineteenth-century that rebelled against virtually every aspect of traditional society. To these radicals, being modern wasn't belonging to an historical era, it was breaking from history altogether to live in a present that seemed fundamentally different from what came before.

Giacomo Balla, Abstract Speed + Sound, 1913-14, oil on millboard in a painted frame, 54.5 x 76.5 cm, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Futurist artists like Balla advocated destroying traditional aesthetics for new styles that reflected the speed and mechanization of the modern era.

The problem with this pose is that history doesn't stop, while the modern approach to history as a subject is based on chronological classifications, or periodization. As time passed, the early decades of the modern movement faded into the distance and Modernism became a spot on the timeline. As a term, Postmodernism makes sense within the classificatory logic of the academic historian, if not in the dictionary.

The ridiculousness of Postmodernism as historical nomenclature makes a nice bridge from fake epistemology to fake historiography.

Webster's defines historiography

Historiography is another technical term that refers to the means by which history is written and understood. Just as epistemology means the parameters by which we construct knowledge, historiography means the ways we construct and organize history.

Not surprisingly, Postmodernists see it differently.

The study of history is especially vulnerable to Postmodern manipulation because it deals with subjects that are difficult to verify empirically, no matter how sincere the historian. The older the civilization, the more difficult it is to provide even the simplest context for the few artifacts that survive. When it comes to the oldest humans, a single discovery can radically reconfigure established chronologies.

Rhyton in the shape of a bull's head, from Knossos, ca. 1500-1450 BCE, serpentine, crystal, and shell inlay (horns restored), 20.6 cm, Archaeological Museum, Iraklion, Crete

The ancient Minoan civilization reached the highest level of technical sophistication known in the Bronze Age before mysteriously disappearing around 1500 BC. The remains of their culture are impressive, but their history is mysterious since scholars have been unable to decipher their language.

Historiography presents an additional vulnerability, since it is an interpretive field and therefore susceptible to "critical" discourse analysis. Postmodernists pay little attention to the material historical record or logical consistency when reimagining history as a set of simplistic, largely erroneous generalizations that can be "unpacked" and "problematized" at will. They also love vague yet important sounding action verbs that make their "interventions" matter on some level. The reality is that history, when done in an intellectually responsible and logically coherent way, follows a familiar empirical model and has little need for odd predicates used in new ways. Of course, Postmodernists have little interest in the reality of anything. Before problematizing their unpackings, however, it is important to consider where history came from, and its place in defining the culture of the West.

The History of History and Historiography

Historically, history is inseparable from writing; in fact, the word prehistoric (that's enough antanaclasis for one post) literally means before the invention of writing. This is not to say that prehistoric cultures had no sense of the past - oral history is a form of history - just that without being able to write things down, there is no way of fixing a record of events that later readers can reference. Obviously, a text is not inherently truthful, and even the most honest historian writes from a subjective viewpoint, but writing created two essential preconditions for the development of history in the West: the ability of scholars across time to read and corroborate the same source material, and the ability to build cumulatively on the recorded observations and insights of the past.

Proto-Cuneiform tablet with record of sheep, c. 3400 BC, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

Cuneiform tablet with entries concerning malt and barley groats, ca. 3100–2900 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The earliest recognized writing system, like other basics of civilization, emerged in ancient Sumeria in the 4th century BC, as a means of standardized record keeping. This tablet represents seven male sheep, and could serve as an inventory or record of transfer.

Accurate record keeping was essential for the development of more complex economic, political, and legal frameworks necessary to manage large-scale civilizations.

It is clear from the origins of writing that the basic building blocks of history were present from the start. To begin with, the very notion of keeping records introduces time, or more accurately, temporality, into communication, because it is intended to fix information from a certain moment for future consumption. Furthermore, there is an implication that the record is accurate, or else it is of little use to its stated purpose of record keeping. This notion of fixity, of preserving reliable facts against the ravages of time, is a precondition for the development of any knowledge domain.

François Chauveau, Allegory of History, 17th century, pen and brown ink, brush and gray wash, over traces of graphite, 16.4 x 18.5 cm

The notion of writing to preserve truth against the ravages of time is visualized in this drawing. The personification of History writes in a text held by Father Time, symbolizing that the record is held by, and emerges from, the past. Note how History look away from Time and her work. She writes for the future.

Works that we might consider explicitly historical, in that narrating past events is their primary focus, reveal that the writing of history was always bound up with politics and religion. How could it not be? The history of a people is, among other things, a document of how it represents its own past, which is invariably tied up with its larger ideas. As the notion of historiography develops, it is impossible to cleanly separate it from contemporary epistemology or metaphysics.

The Flood Tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet 11), Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BC, clay, British Museum, London

Sumerian King List, c. 1800 BC, clay, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Early history is inseparable from mythology, since the beliefs regarding the origins of the world belong to both. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest know narrative, involves gods, heroes, and other supernatural beings, but is also set in what is presented as the real past.

As a chronological list of rulers, the Sumerian King List is an extremely important historical artifact, but the further the entries are from the 19th century BC when the list was made, the more legendary they become. Notably, Gilgamesh is included, which raises a question for historians trying to untangle this: were mythological beings included in the royal tale, or did real figures transform into gods over time in popular memory?

Historiography, or the conscious study of what legitimately constitutes history, begins, like so many theoretical pursuits, with the Greeks. Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC) completed The Histories (The Persian Wars), his sweeping account of the Greco-Persian wars around 440 BC, which led the Roman Cicero to refer to him as the Father of History. Herodotus has no real predecessor in his attempt to present a comprehensive accounting of significant recent events in terms of human cause and effect. The gods still play a role in his work, and events are told in a literary manner, but The Histories define historical events as a distinct subject worthy of study. Herodotus also established the connection between history and national identity from the outset.

Greek hoplite and Persian warrior, 5th century BCE, red figure pottery, National Archaeological Museum of Athens

In The Histories, Herodotus cast the Persian Wars in moral terms, with the Greeks fighting off a vastly powerful foreign empire. Many interpret this conflict as the beginning of a long struggle between East and West, though these geopolitical terms are an anachronism. It is more accurate to characterize this as a clash between freedom and the dignity of the individual and and collectivist, imperial tyranny.

Herodotus introduced some lasting traits in historiography: history as defining a national identity, preferably through a national struggle; history as fulfilling a divine or supernatural plan; and history as the result of heroic deeds by great men. His younger contemporary Thucydides (460-395 BC) refined the notion of history with his The History of the Peloponnesian War, which covered the years 431-404 BC of the disastrous conflict that ended the classical era in Greece. This work removed the gods altogether, and told the story as a series of purely human actions. Thucydides also a presented at least an air of impartiality, introducing the notion of "scientific" objectivity to history writing. It should be pointed out that Thucydides himself was not "objective." His work is famous for its speeches; detailed transcripts of orations that he could not have possibly been present for, but which recount the reasoning behind actions and drive the narrative.

Pericles pronouncing the funeral oration of the Athenian soldiers, 1897, in John Clark Ridpath, Ridpath's Universal History, vol. 3, p. 130.

Thucydides' creative, or literary, embellishment becomes another historiographic commonplace: a willingness to massage the specific facts to clarify the larger picture. The impartial recounting of facts and the need to distill a larger story are related and conflicting impulses that never leave the writing of history.

The emphasis on the individual actor, and even the gods, in history is consistent with Greek ideas about ontology. Put simply, they did not perceive the movement of time as teleological, meaning that the flow of history did follow some larger governing purpose or pattern. How could it? The Greek creation myth began with the spontaneous generation of primordial deities like Gaia and Ouronos (Earth and Sky) out of Chaos, who then mate, producing generations of divine offspring that overthrow their parents. Zeus, the famous king of the Olympian gods, is the grandson of Gaia and Ouronos, putting him and his fellows far from the origins of the universe. The gods rule by force and guile, not by nature, and while they create humanity, it is more of a whim then the fulfillment of a cosmic plan. Meanwhile monsters lurk beyond the fringes of civilization as a constant reminder of the fragility of society.

Niobid Painter, Artemis and Apollo slaying the children of Niobe, Athenian red-figure calyx krater, circa 450 BCE

In their dealings with mortals, the Greek gods seem like nothing more than super-powered people, rather than representatives of transcendent principles. In this myth, two gods murder the fourteen children of Niobe to avenge her slight against their mother. One may make offerings to the gods, but there is no equivalent to the certainty of Christian salvation theology.

For the Greeks, chaos was the base state of affairs and order a constant struggle of intelligence, strength, and will against entropy. As created beings in the cosmos, the gods are as bound by this reality as mortals, which is why the later Neoplatonic philosophers could slot them between humans and the World Soul so easily. The histories of Herodotus and Thucydides reflect this world view by defining Greek culture as tenuous and threatened, both from without and within. The Histories offer a founding struggle where Greek order is defended and defined against a tyrannical foreign threat, while The Peloponnesian War details the fragility of even the most enlightened societies in the face of a lust for power and loss of traditional virtues. Given this mentality, heroic individuals were praised for imposing their wills on events, while "ordinary" Greeks sought to preserve their own personal histories for posterity.

Marble stele of a youth and a little girl, Archaic, ca. 530 BCE, 423.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Greek funerary monuments were a form of personal history. They recorded idealized images of the dead to ensure that they would be remembered in the future.

The memory of the dead was a form of immortality in a culture without a clearly defined sense of afterlife.

The place of the individual within history is also linked to the Greek world view. Without a larger teleology or cosmic plan, life has no greater ontological purpose, certainly nothing comparable to the Christian path of salvation. Like any ancient people, the Greeks believed in an afterlife, but it was not fleshed out theologically, and the spirits of the dead are described as palid shades rather than the highest part of themselves. It is what happens in this world that is significant, which leads to a very different notion of immortality than that of the soul: the triumph of fame over death. Fame, or collective memory, preserved the name of the deceased, allowing him to "live on" in the world of the living.

Discobolus, (Discus-thrower), Roman copy of a bronze by Myron of the 5th century BC, British Museum

Brygos Painter, Alcaeus and Sappho, Attic red-figure kalathos, ca. 470 BC, Staatliche Antikensammlung, Munich

The Greek emphasis on the individual drove artistic interest in the idealized body. It also accounts for the memorialization of sculptors like Myron and poets like Alcaeus and Sappho. Other ancient cultures did not celebrate individual achievement in this way

Like so many other aspects of Greek culture, the version of classical history that made it into the Western tradition was filtered through the Romans. But the culture that Rome absorbed had already been changed by Alexander the Great, who unified Greece before conquering a vast eastern empire. This period was known as the Hellenistic age, and it spread Greek thinking as far as India, while diluting the traditional sense of uniqueness and independence that shines through in Herodotus. Thucydides' image of small, homogenous, fiercely independent polities was replaced with an imperial, aristocratic cosmopolitanism infused with "foreign" ideas. Alexander even claimed divine status for himself, an appropriation of the Egyptian or Persian idea of god-king that was alien to Greek political thought, and caused a rift with his teacher Aristotle. Hellenistic culture set the table for the syncretism that we observed in late antique religion and philosophy, and created a suitable image of rulership for the Roman emperors.

Augustus of Prima Porta, 1st century AD, marble, 2.03 m, Vatican Museums

This statue is a Roman original, but Hellenistic Greek in style. The idealized body, calm expression and realistic detail are typical. A painted cast is included as a reminder that the ancient Greeks and Romans painted their sculpture; the plain marble reflects later tastes, and many statues were "cleaned" in the pre-modern era.

The breastplate represents the establishment of imperial rule with symbolic figures including gods. His personal history, political history, and metaphysical history all come together.

Augustus laid the foundation for the Imperial Cult, the belief that the emperors became gods, which brought personal and world history together in an interesting way. Actual divinization added a metaphysical dimension to the idea of immortality as a consequence of personal history or fame, transforming it from mnemonic to spiritual reality. This achievement-based ascension is known as apotheosis.

Apotheosis of Claudius, mid-1st century AD, sardonyx cameo, Inv. No. Camee. 265, Paris, National Library

Apotheosis imagery like this cameo combines the ability of personal history to achieve immortality through memory and spiritual transfer, sometimes in ways that are difficult to distinguish. Here, a winged Victory or Fame crowns Claudius with laurel, a traditional symbol of achievement and triumph, while an eagle, a symbol of metaphysical transition, carries him heavenward.

National and personal history came together in Virgil's Aeneid, an epic poem that told of the mythic founding of Rome after years of wandering by Aeneas, a Trojan prince and son of the goddess Venus who escaped the sack of that city. This story replaced the older Etruscan myth of the founding of the city by the brothers Romulus and Remus, and reflects the growing popularity of Greek culture in imperial Rome. Virgil created a national "history" that naturalized the Roman adoption of Greek forms of expression and Augustus' own Hellenistic image of rulership.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus, Livia, and Octavia, 1809-19, pen and ink, graphite, watercolor, gouache, 38.1 x 32.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

In this drawing, neoclassical painter Ingres depicts Virgil reading his poem to the emperor and his sister. Octavia's faint is a sign of the emotional power of the piece. Notice Virgil's own laurel crown, a sign of his triumphal fame.

This brief historical sketch allows us to identify the key elements that emerged in ancient historiography. Questions of accuracy, authorial ideology, individual and collective foci, and the role of teleology and other supernatural elements are all still relevant to history in the West today.

Anton Raphael Mengs, The Triumph of History over Time (Allegory of the Museum Clementinum), 1772, ceiling fresco, Camera dei Papiri, Vatican Library

No one will be surprised to see Postmodernism make a mess of this in the usual ways, ignoring empirical data and promoting baseless theories of human behavior on misdirected faith.

This fairy tale, another in an endless attempt to appropriate cultural achievements for a region with precious few, generated "heat" in academia, because intelligent people who know better are afraid of being called racist. On one side, we have a lack of material evidence, credulity towards myth that belongs in Chariots of the Gods, and inept philology; on the other, well, Bernal really wants it to be true. Ladies and gentlemen, Postmodern history.

The fundamental difference between historiography and Postmodern "historiography" is one of intention. The former seeks the most effective way to recount the past as truthfully as possible, while the latter defines "truth" as oppressive discourse and forces all findings into a predetermined conclusion.

Philosophical and historical errors combine in the absurd concept of secular transcendence, a series of lies intended to fool the credulous into believing that one could reject the supernatural ontologically, but still claim history follows a larger teleology or progress. In this way historians can become god-kings of a sort, in that they are privy to higher "truths" without any metaphysical standard to check their lust for power.

Incredibly, despite the countless lives lost and societies ruined, this sociopathic toxin still spews from academia, and probably will as long as the institutions prefer substandard credentialists to thinkers. Lacking the intellectual ability to assess sources critically and independently, it is inevitable that "scholars" will slavishly tie themselves to a well-known Philosopher's Name, no matter how debased.

Empirically speaking, history does not move by Hegelian dialectic, 19th century misconceptions about economics and teleology are not historiography, and "social class" is preceded developmentally by genetics and environment. The fact that Marx was a self-promoting scientific and historical illiterate is clear, but this does not excuse people today who follow his errors.

As with Postmodern epistemology in general, Postmodern history commits the category error of locating top-down transcendentals in the empirical world, where they are subject to evaluation. Of course, because they unknowingly accept these errors as articles of faith, cognitive dissonance and often aggression ensue. Were Postmodernists honest, they would abandon fictions like blank slate equality once they failed empirically, but they are more like doomsday cultists, pushing their demented faith despite all evidence of its destructiveness, until they collapse the system and are consumed in the aftermath. Christian historiography, makes for an interesting contrast, since it not strictly empirical, but locates the transcendent where it belongs.

Christ as Alpha and Omega, late 4th century, mural painting from the Catacombs of Commodilla, Rome

Remember that Christian ontology differed from Neoplatonism in positing a motivated and benevolent God as the ultimate reality. This means all time unfolds within God's plan for creation, a divine teleology from Genesis to Revelations. In this picture Christ, or God made visible, is flanked by the Greek letters alpha and omega, symbolizing the beginning and end of time.

In this system, individual history becomes oriented towards salvation rather than worldly fame.

The Good Shepherd, mid-3rd century, mural painting from the Catacomb of Callixtus, Rome

The earliest Christian images didn't depict Christ directly, but used symbolic images and figures to represent him. The Good Shepherd was an ancient pagan motif associated with protection that was converted to a symbol of Jesus.

Since Christ is God on an ontological level, we can combine the alpha and the omega from the picture above with the benevolent nature of the Good Shepherd to visualize Christian historical teleology. Like the One of the Neoplatonists, God is the transcendent source of everything, but unlike the One, He has a plan for creation that reflects His own ultimate goodness. This underlying divine motivation is often called providence.

Within this benevolent teleological structure, the only historical "dates" that matter are the Creation and Last Judgment, or beginning and end of the world, and the events around the life of Christ, which open the way to salvation. From a Christian perspective, this world is fallen as a result of Original Sin, which is a much more profound issue than snide criticisms of eating an apple would have it. Symbolically, the expulsion from Eden is a good metaphor for the loss of innocence through experience. But theologically, it represents turning away from the God's plan to follow one's own authority, and since God is ultimate reality this means choosing deluded pride over Truth. Satan is the template for the ontological self-erasure that comes from rejecting the nature of reality, and Adam and Eve recreate this error on a human level. Everything that follows their entry into the world is a consequence of this prideful blindness, and while Christ's sacrifice offers redemption on an individual level, even this is only realized after death. There is therefore no intrinsic value in the worldly accomplishments of fallen beings and fame and power are of no consequence for entry into heaven.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, The Tower of Babel, 1563, oil on panel, 114 x 155 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The story of the Tower of Babel, a human collaboration to reach heaven on their own was brought to an abrupt end by God. The lesson, as always, is that vain, finite human creatures cannot achieve transcendence on their own devices. It is a lesson that humans struggle with.

The Band is not the first to note the similarity between the Tower of Babel and the EU Parliament in Strasbourg. It appears this monument to human vanity will prove as successful as the prototype.

Worldly achievement is irrelevant in the face of divine teleology, but personal history becomes all-important. If the culmination of history is a final, metaphysical judgment, living the virtuous life necessary to secure a positive outcome is essential. This is not circumstantial; salvation is essentially open to anyone anywhere who accepts Christian doctrine on faith.

Hans Memling, The Last Judgment, 1467-71, National Museum, Gdańsk, Poland

The Last Judgment is the end or telos of Christian history, and it gives ultimate meaning to human life as well. Worldly achievement and fame means nothing here. To quote Matthew, "it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God" (Matthew 19:24, KJV).

There are two common forms of medieval historical writing that manage to fit within this structure, both of which are significantly different from modern notions of history: inspiring tales of saints and miracles, and chronicles. The former takes people and events out of their context to presents them as inspirational and behavioral role models. Chronicles record significant events in a chronological listing without interpretation of causality or deeper significance.

Twelfth-Century Chronicle page (f. 61), mid-12th century, with additions up to 1266, 25 x 16 cm, British Library, Harley 3775. The second part of this manuscript includes a chronicle history of central England from AD 1 to 1266 (ff. 61v-73)

A chronicle is an accounting of events year by year like a timeline. This one begins with the birth of Christ and moves forward to the time of the author. No lessons or interpretations are provided, because worldly events ultimately are meaningless in the overall scheme of things.

The chronicle histories of the Middle Ages can be thought of as a tale of years, or lists of dates and things that happened. The more ambitious ones incorporate early Biblical history and marvelous occurrences along with more current events, but all become focused on the local region as the chronology gets more recent. The European nations, with their distinct cultures, evolved organically out of the post-classical landscape around tribal and geographic identity. Christianity was the thread that gave them a shared affiliation. Chronicle historiography that recounts local events within a universal Christian context expresses this uniquely Western process of nation-forming. Since the the ebbs and flows of human societies are ultimately meaningless from teleological perspective, there is no interest in wider historiographic theory and interpretation. Of course, presenting things from a proto-nationalist point of view, or to legitimate a political structure, is a form of historical interpretation, it just isn't self-consciously theoretical.

Jean Fouquet, Coronation of Philippe Auguste in 1179, circa 1455, from the Grandes Chroniques de France, Paris, BNF Français 6465, f. 212v.

In this illumination, we see the connection between historical events (the coronation), French national identity (the royal heraldry of gold fleur-de-lys on blue field), and Christianity (the clergy crowns the king, representing God's sanction). The king, dressed in the same regalia as the setting, is the divinely ordained personification of the French people.

Humanism and History

The Renaissance is far too large and significant a cultural and historical movement to attempt to sum up in a blog post, and historians are still trying to determine its full nature and scope. What we can do is identify some broad historiographic transformations that came out of the interest in ancient learning that characterized that period. But first, an important note on the relationship between the Renaissance and antiquity. It is a misconception, initially promoted to denigrate the intellectual achievements of the Middle Ages, that classical ideas disappeared altogether after the fall of the Western Empire. This falsehood has since allowed Postmodern "historians" to fabricate the myth that Europe was dependent on Muslim sources for ancient learning. Actual historians have noted "Renaissances" in the West since the time of Charlemagne (777-815). (Click for a good collection of artworks that show the transition from late antiquity to the Western, Byzantine, and Islamic medieval cultures). What is significant about the Italian Renaissance is the depth and intensity of focus on the language and culture of the ancient world, and the elevation of secular knowledge as an end in itself to the highest tier of Western epistemology.

Equestrian Statue of a Carolingian Emperor (perhaps Charlemagne's grandson, Charles the Bald), 9th century, bronze, Louvre, Paris

The bronze mounted emperor portrait was an ancient Roman symbol of honor and power. This figure is dressed in a medieval costume rather than a classical one, but the connotations of imperial authority are unmistakable, especially since this sort of image had not been seen since antiquity. By reviving this custom, the Carolingians defined their rule for posterity in terms of worldly classical glory. It is ironic that we are uncertain who this was, but unlike Postmodernists, we don't believe that the failure of a historical gesture to signify fully means that the gesture never happened.

The Italian Renaissance differed from earlier medieval interest in ancient ideas in depth and scope. In the bronze statue of the emperor above, the costume and style of the figure do not attempt to imitate classical models. The general Roman association between riding a horse and imperial power is sufficient to add meaning to what is basically an early medieval figure. In the Renaissance, the antique world became valued on its own terms, driving a sustained effort to revive classical language and culture in more historically accurate ways. It is not an exaggeration to claim that the modern historical disciplines - antiquarianism, archaeology, art history, philology, classics, comparative literature, historiography, etc. - have their roots in Renaissance interpretations of ancient sources. This movement, which transformed Western epistemology, is most commonly known as humanism, or Renaissance humanism, to distinguish it from secular humanism, its wackier modern cousin.

Sandro Botticelli, St. Augustine in his Study, 1480, fresco, 152 cm × 112 cm, Ognissanti, Florence

In this image, the famous Renaissance painter has reimagined the Father of the Western Church as a humanist scholar. His shelf is lined with the trappings of secular learning, including an orrery, manuscript of Euclidean geometry, and a clock. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Renaissance established an archetypal image of a scholar that defined Western academia until Modernity.

Note that there is no conflict between his learning and his faith. His bishop's miter is right by his elbow.

Humanist scholars first appear in fourteenth-century Italy, although the socio-economic roots of the movement are older. They got their name from their subject of study - the studia humanitatis or human-centered knowledge - which was more or less synonymous with ancient learning at the time. The term distinguished them from the Scholastic philosophers of the universities, and a large part of humanist self-representation, or branding, was in opposition to Thomistic medieval theology. The humanists were unequivocally Christian, but promoted Greco-Roman ideas as a guide to more virtuous living, ultimately giving antiquity a cultural authority that in hindsight was an act of unacknowledged faith. Whatever the motives, the Renaissance brought classical rhetoric and epistemology back into the center of Western thought, which from a historiographic perspective, meant ancient ideas about worldly achievement and immortality had to be accommodated to a Christian context.

Bernardo Rossellino, Tomb of Leonardo Bruni, 1444-47, marble, 610 cm, Santa Croce, Florence

Bruni was an eminent Florentine humanist, and his tomb mixes Classical and Christian values. His effigy and inscription indicate individual achievement and fame, while the Madonna and Child above confirm his faith in salvation.

Over time, fame and achievement became ends in themselves. It is difficult for the afterlife to compete with immediate rewards, given human time preferences and dopamine.

We can revisit the epistemology graphic from the previous post to visualize the broad outline of this union of Classical and Christian historiography. The distinction between empirical and top-down thinking will wait until the next post, when we tackle the errors and lies of Postmodernism more directly. It is, after all, necessary to understand a healthy physiology before excising a tumor. We can replace the three levels of reality with equivalent levels of history: personal, collective (national, cultural, world, etc.) and metaphysical. Supernatural forces like providence or any other teleology belong at the metaphysical level, beyond empirical validation, where they are accepted or rejected on faith. One cannot falsify the Creation, Incarnation, or Last Judgment, so they do not fit within historical standards of evidence. Classical history lacks teleology, so it focuses on the significance of human activity at the collective level. The two are really not compatible, but they do occupy different historiographic levels, and and can be made to coexist.

At the personal level, things get more complex. Both traditions place value on the outcomes of a personal history of virtue, only the virtues and outcomes reflect very different ethical systems. The ability to synthesize these (somewhere, Hegel is smiling) was a uniquely Western development, and critical for the innovations (and pitfalls) that followed. Classical fame and achievement in this world, tempered by a Christian historical teleology, provided the potential for a theoretical balance between the excesses of spiritual detachment and naked ambition.

By treating secular pagan knowledge as inherently worthwhile, the Renaissance opened the door to theoretical reflections on subjects that were not of interest to medieval thinkers. Classical historiography replaced the chronicle with interpretative narratives about the meaning of human history.

Leonardo Bruni, Historiae Florentini populi, late fifteenth century, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Pluteo 65.8, c. 1r.

Humanist Bruni's History of the Florentine People recounted the greatness of the Florentines and their role in cultural renewal, in a manner reminiscent of ancient Roman historians. The idea of celebrating the secular achievements and destiny of a people is foreign to the medieval chronicle tradition, and is a direct result of the Renaissance absorption of classical historiography.

Bruni also prepared manuscript histories of ancient subjects, such as the Punic Wars.

The Renaissance transformation of history goes beyond new types of works like Bruni's to a rethinking of the subject as a whole. To generalize, Classical historiography saw the world as a-teleological, and history a sequence of great individuals and peoples carving fame and order out of essentially chaos. The difference between eras was unimportant in the larger scheme of things, and any individual was worthy of celebration if sufficiently great. The Persian conqueror Cyrus the Great was praised by Greek historians, and Aeschylus even managed to make Xerxes a tragic hero. Medieval Christian historiography was teleological in a metaphysical sense, which meant the the ebbs and flows of human affairs were ultimately unimportant. The relative difference in size and power between imperial Rome and the early medieval kingdoms was irrelevant next to the fact that the former were pagan and the latter had the potential for salvation. But the Renaissance, literally rebirth, was a self-conscious historical and cultural revival, meaning that people began thinking about history in terms of eras or periods for the first time.

Justus van Gent, Francesco Petrarca, circa 1472-76, oil on panel, 112 x 58 cm, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

Petrarch (1304-74) is often considered the first Renaissance humanist, and was certainly an inspiration to the following generations like Bruni. He introduced the idea that history of historical decline when he judged the cultural achievements of classical antiquity to be superior to his own times. The Renaissance that followed began as an attempt to remedy this loss. Note the familiar laurel crown signifying triumph and immortality in Classical terms.

Thinking of history in terms of loss and rebirth introduced the notion that periods can be characterized and compared on secular grounds. The use of the term Dark Ages in reference to Medieval Europe was a Renaissance invention, since the Classical heritage had to be lost in order to be recovered. The fact that this completely misrepresented medieval culture is irrelevant, and the strength of the peak - decline - rebirth model is apparent in the fact that we still refer to "the Middle Ages" today.

By reimagining history in terms of decline and rebirth, humanists introduced concepts of unified movement and value to secular affairs. This wasn't exactly teleological, since it had no final end, but did lend itself to thinking about progress in strictly worldly terms. As the first appearance of an abstract historical construct, it gave historiography a theoretical dimension that opened the way for all the top-down misconceptions that followed. This brings us back to the question that opened this post. How, in any abstract system of this kind, can the present be "post" modern? The short answer is that it can't, but there is a lot of Postmodern word salad to pass through before you can get there. We'll blow that up next.

This historical overview was longer than planned, but it is important to be precise about what we mean by historiography, or the legitimate construction of historical knowledge. But given the length, it makes sense to let it stand as an introduction and move into the jumbled historical fables the next post. That will start with something like this:

Fortunio Liceti, De monstrorum caussis, natura, et differentiis libri duo…, 1634, engraved title page

Pre-modern monsters were generally conceived as distortions, perversions, and/or amalgamations of natural creatures. By rejecting empiricism, Postmodernism twists faith into a monstrous parody of epistemology.

The epistemological failure of Postmodernism makes it impossible for it to come up with anything resembling a coherent ontology. Without the ability to construct legitimate knowledge, its downstream deductions are invariably wrong with no capacity to learn empirically from those errors. This blog began by looking one such whopper - the idiocy of asserting discursively that discourse is meaningless - before pointing out that whoever controls the discourse controls reality. It is not a coincidence that the left targeted the knowledge and culture industries so aggressively. How better to pass off monstrous fictions as knowledge?

Marxist riot at Berkeley, the purported home of "free speech" in Boomer mythology. The lack of institutional response suggests that the abrogation of their stated intellectual mission is intentional.

This leads to the self-evident absurdity of Postmodern history: how can the present be "post" modern?

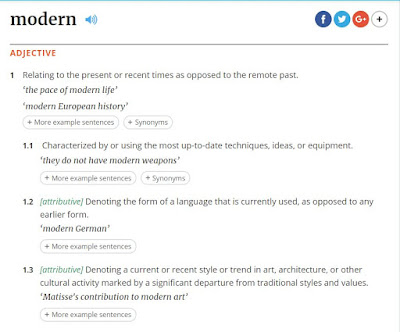

Consider the definition of "modern" provided by the Oxford Dictionary website. The variations all refer to the present day in some way or another. How can something that originated a half century ago be "post" that?

Are we living in the future?

The problem emerged when the word modern morphed into Modernism, a period of rapid cultural change beginning in the nineteenth-century that rebelled against virtually every aspect of traditional society. To these radicals, being modern wasn't belonging to an historical era, it was breaking from history altogether to live in a present that seemed fundamentally different from what came before.

Giacomo Balla, Abstract Speed + Sound, 1913-14, oil on millboard in a painted frame, 54.5 x 76.5 cm, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Futurist artists like Balla advocated destroying traditional aesthetics for new styles that reflected the speed and mechanization of the modern era.

The problem with this pose is that history doesn't stop, while the modern approach to history as a subject is based on chronological classifications, or periodization. As time passed, the early decades of the modern movement faded into the distance and Modernism became a spot on the timeline. As a term, Postmodernism makes sense within the classificatory logic of the academic historian, if not in the dictionary.

No, we are not living in the future

Late Modernity had an optimistic vision of the future. Postmodernity was somewhat less positive.

No flying cars, but slave markets are back! Plus one for globalism.

The ridiculousness of Postmodernism as historical nomenclature makes a nice bridge from fake epistemology to fake historiography.

Webster's defines historiography

Historiography is another technical term that refers to the means by which history is written and understood. Just as epistemology means the parameters by which we construct knowledge, historiography means the ways we construct and organize history.

Not surprisingly, Postmodernists see it differently.

The study of history is especially vulnerable to Postmodern manipulation because it deals with subjects that are difficult to verify empirically, no matter how sincere the historian. The older the civilization, the more difficult it is to provide even the simplest context for the few artifacts that survive. When it comes to the oldest humans, a single discovery can radically reconfigure established chronologies.

Rhyton in the shape of a bull's head, from Knossos, ca. 1500-1450 BCE, serpentine, crystal, and shell inlay (horns restored), 20.6 cm, Archaeological Museum, Iraklion, Crete

The ancient Minoan civilization reached the highest level of technical sophistication known in the Bronze Age before mysteriously disappearing around 1500 BC. The remains of their culture are impressive, but their history is mysterious since scholars have been unable to decipher their language.

Historiography presents an additional vulnerability, since it is an interpretive field and therefore susceptible to "critical" discourse analysis. Postmodernists pay little attention to the material historical record or logical consistency when reimagining history as a set of simplistic, largely erroneous generalizations that can be "unpacked" and "problematized" at will. They also love vague yet important sounding action verbs that make their "interventions" matter on some level. The reality is that history, when done in an intellectually responsible and logically coherent way, follows a familiar empirical model and has little need for odd predicates used in new ways. Of course, Postmodernists have little interest in the reality of anything. Before problematizing their unpackings, however, it is important to consider where history came from, and its place in defining the culture of the West.

The History of History and Historiography

Historically, history is inseparable from writing; in fact, the word prehistoric (that's enough antanaclasis for one post) literally means before the invention of writing. This is not to say that prehistoric cultures had no sense of the past - oral history is a form of history - just that without being able to write things down, there is no way of fixing a record of events that later readers can reference. Obviously, a text is not inherently truthful, and even the most honest historian writes from a subjective viewpoint, but writing created two essential preconditions for the development of history in the West: the ability of scholars across time to read and corroborate the same source material, and the ability to build cumulatively on the recorded observations and insights of the past.

Proto-Cuneiform tablet with record of sheep, c. 3400 BC, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

Cuneiform tablet with entries concerning malt and barley groats, ca. 3100–2900 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The earliest recognized writing system, like other basics of civilization, emerged in ancient Sumeria in the 4th century BC, as a means of standardized record keeping. This tablet represents seven male sheep, and could serve as an inventory or record of transfer.

Accurate record keeping was essential for the development of more complex economic, political, and legal frameworks necessary to manage large-scale civilizations.

It is clear from the origins of writing that the basic building blocks of history were present from the start. To begin with, the very notion of keeping records introduces time, or more accurately, temporality, into communication, because it is intended to fix information from a certain moment for future consumption. Furthermore, there is an implication that the record is accurate, or else it is of little use to its stated purpose of record keeping. This notion of fixity, of preserving reliable facts against the ravages of time, is a precondition for the development of any knowledge domain.

François Chauveau, Allegory of History, 17th century, pen and brown ink, brush and gray wash, over traces of graphite, 16.4 x 18.5 cm

The notion of writing to preserve truth against the ravages of time is visualized in this drawing. The personification of History writes in a text held by Father Time, symbolizing that the record is held by, and emerges from, the past. Note how History look away from Time and her work. She writes for the future.

Works that we might consider explicitly historical, in that narrating past events is their primary focus, reveal that the writing of history was always bound up with politics and religion. How could it not be? The history of a people is, among other things, a document of how it represents its own past, which is invariably tied up with its larger ideas. As the notion of historiography develops, it is impossible to cleanly separate it from contemporary epistemology or metaphysics.

The Flood Tablet from the Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet 11), Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BC, clay, British Museum, London

Sumerian King List, c. 1800 BC, clay, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Early history is inseparable from mythology, since the beliefs regarding the origins of the world belong to both. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest know narrative, involves gods, heroes, and other supernatural beings, but is also set in what is presented as the real past.

As a chronological list of rulers, the Sumerian King List is an extremely important historical artifact, but the further the entries are from the 19th century BC when the list was made, the more legendary they become. Notably, Gilgamesh is included, which raises a question for historians trying to untangle this: were mythological beings included in the royal tale, or did real figures transform into gods over time in popular memory?

Historiography, or the conscious study of what legitimately constitutes history, begins, like so many theoretical pursuits, with the Greeks. Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC) completed The Histories (The Persian Wars), his sweeping account of the Greco-Persian wars around 440 BC, which led the Roman Cicero to refer to him as the Father of History. Herodotus has no real predecessor in his attempt to present a comprehensive accounting of significant recent events in terms of human cause and effect. The gods still play a role in his work, and events are told in a literary manner, but The Histories define historical events as a distinct subject worthy of study. Herodotus also established the connection between history and national identity from the outset.

Greek hoplite and Persian warrior, 5th century BCE, red figure pottery, National Archaeological Museum of Athens

In The Histories, Herodotus cast the Persian Wars in moral terms, with the Greeks fighting off a vastly powerful foreign empire. Many interpret this conflict as the beginning of a long struggle between East and West, though these geopolitical terms are an anachronism. It is more accurate to characterize this as a clash between freedom and the dignity of the individual and and collectivist, imperial tyranny.

Herodotus introduced some lasting traits in historiography: history as defining a national identity, preferably through a national struggle; history as fulfilling a divine or supernatural plan; and history as the result of heroic deeds by great men. His younger contemporary Thucydides (460-395 BC) refined the notion of history with his The History of the Peloponnesian War, which covered the years 431-404 BC of the disastrous conflict that ended the classical era in Greece. This work removed the gods altogether, and told the story as a series of purely human actions. Thucydides also a presented at least an air of impartiality, introducing the notion of "scientific" objectivity to history writing. It should be pointed out that Thucydides himself was not "objective." His work is famous for its speeches; detailed transcripts of orations that he could not have possibly been present for, but which recount the reasoning behind actions and drive the narrative.

Pericles pronouncing the funeral oration of the Athenian soldiers, 1897, in John Clark Ridpath, Ridpath's Universal History, vol. 3, p. 130.

Thucydides' creative, or literary, embellishment becomes another historiographic commonplace: a willingness to massage the specific facts to clarify the larger picture. The impartial recounting of facts and the need to distill a larger story are related and conflicting impulses that never leave the writing of history.

The emphasis on the individual actor, and even the gods, in history is consistent with Greek ideas about ontology. Put simply, they did not perceive the movement of time as teleological, meaning that the flow of history did follow some larger governing purpose or pattern. How could it? The Greek creation myth began with the spontaneous generation of primordial deities like Gaia and Ouronos (Earth and Sky) out of Chaos, who then mate, producing generations of divine offspring that overthrow their parents. Zeus, the famous king of the Olympian gods, is the grandson of Gaia and Ouronos, putting him and his fellows far from the origins of the universe. The gods rule by force and guile, not by nature, and while they create humanity, it is more of a whim then the fulfillment of a cosmic plan. Meanwhile monsters lurk beyond the fringes of civilization as a constant reminder of the fragility of society.

Niobid Painter, Artemis and Apollo slaying the children of Niobe, Athenian red-figure calyx krater, circa 450 BCE

In their dealings with mortals, the Greek gods seem like nothing more than super-powered people, rather than representatives of transcendent principles. In this myth, two gods murder the fourteen children of Niobe to avenge her slight against their mother. One may make offerings to the gods, but there is no equivalent to the certainty of Christian salvation theology.

For the Greeks, chaos was the base state of affairs and order a constant struggle of intelligence, strength, and will against entropy. As created beings in the cosmos, the gods are as bound by this reality as mortals, which is why the later Neoplatonic philosophers could slot them between humans and the World Soul so easily. The histories of Herodotus and Thucydides reflect this world view by defining Greek culture as tenuous and threatened, both from without and within. The Histories offer a founding struggle where Greek order is defended and defined against a tyrannical foreign threat, while The Peloponnesian War details the fragility of even the most enlightened societies in the face of a lust for power and loss of traditional virtues. Given this mentality, heroic individuals were praised for imposing their wills on events, while "ordinary" Greeks sought to preserve their own personal histories for posterity.

Marble stele of a youth and a little girl, Archaic, ca. 530 BCE, 423.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Greek funerary monuments were a form of personal history. They recorded idealized images of the dead to ensure that they would be remembered in the future.

The memory of the dead was a form of immortality in a culture without a clearly defined sense of afterlife.

The place of the individual within history is also linked to the Greek world view. Without a larger teleology or cosmic plan, life has no greater ontological purpose, certainly nothing comparable to the Christian path of salvation. Like any ancient people, the Greeks believed in an afterlife, but it was not fleshed out theologically, and the spirits of the dead are described as palid shades rather than the highest part of themselves. It is what happens in this world that is significant, which leads to a very different notion of immortality than that of the soul: the triumph of fame over death. Fame, or collective memory, preserved the name of the deceased, allowing him to "live on" in the world of the living.

Discobolus, (Discus-thrower), Roman copy of a bronze by Myron of the 5th century BC, British Museum

Brygos Painter, Alcaeus and Sappho, Attic red-figure kalathos, ca. 470 BC, Staatliche Antikensammlung, Munich

The Greek emphasis on the individual drove artistic interest in the idealized body. It also accounts for the memorialization of sculptors like Myron and poets like Alcaeus and Sappho. Other ancient cultures did not celebrate individual achievement in this way

Like so many other aspects of Greek culture, the version of classical history that made it into the Western tradition was filtered through the Romans. But the culture that Rome absorbed had already been changed by Alexander the Great, who unified Greece before conquering a vast eastern empire. This period was known as the Hellenistic age, and it spread Greek thinking as far as India, while diluting the traditional sense of uniqueness and independence that shines through in Herodotus. Thucydides' image of small, homogenous, fiercely independent polities was replaced with an imperial, aristocratic cosmopolitanism infused with "foreign" ideas. Alexander even claimed divine status for himself, an appropriation of the Egyptian or Persian idea of god-king that was alien to Greek political thought, and caused a rift with his teacher Aristotle. Hellenistic culture set the table for the syncretism that we observed in late antique religion and philosophy, and created a suitable image of rulership for the Roman emperors.

Augustus of Prima Porta, 1st century AD, marble, 2.03 m, Vatican Museums

This statue is a Roman original, but Hellenistic Greek in style. The idealized body, calm expression and realistic detail are typical. A painted cast is included as a reminder that the ancient Greeks and Romans painted their sculpture; the plain marble reflects later tastes, and many statues were "cleaned" in the pre-modern era.

The breastplate represents the establishment of imperial rule with symbolic figures including gods. His personal history, political history, and metaphysical history all come together.

Augustus laid the foundation for the Imperial Cult, the belief that the emperors became gods, which brought personal and world history together in an interesting way. Actual divinization added a metaphysical dimension to the idea of immortality as a consequence of personal history or fame, transforming it from mnemonic to spiritual reality. This achievement-based ascension is known as apotheosis.

Apotheosis of Claudius, mid-1st century AD, sardonyx cameo, Inv. No. Camee. 265, Paris, National Library

Apotheosis imagery like this cameo combines the ability of personal history to achieve immortality through memory and spiritual transfer, sometimes in ways that are difficult to distinguish. Here, a winged Victory or Fame crowns Claudius with laurel, a traditional symbol of achievement and triumph, while an eagle, a symbol of metaphysical transition, carries him heavenward.

National and personal history came together in Virgil's Aeneid, an epic poem that told of the mythic founding of Rome after years of wandering by Aeneas, a Trojan prince and son of the goddess Venus who escaped the sack of that city. This story replaced the older Etruscan myth of the founding of the city by the brothers Romulus and Remus, and reflects the growing popularity of Greek culture in imperial Rome. Virgil created a national "history" that naturalized the Roman adoption of Greek forms of expression and Augustus' own Hellenistic image of rulership.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus, Livia, and Octavia, 1809-19, pen and ink, graphite, watercolor, gouache, 38.1 x 32.3 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

In this drawing, neoclassical painter Ingres depicts Virgil reading his poem to the emperor and his sister. Octavia's faint is a sign of the emotional power of the piece. Notice Virgil's own laurel crown, a sign of his triumphal fame.

This brief historical sketch allows us to identify the key elements that emerged in ancient historiography. Questions of accuracy, authorial ideology, individual and collective foci, and the role of teleology and other supernatural elements are all still relevant to history in the West today.

Neoclassicist Mengs captures the elements of classical historiography that carried into pre-modern Europe in a single image. Clio, the ancient Muse of History sits writing, while a genius of youth and Chronos, the god of time, flank her, symbolizing the role of history in overcoming the ravages of time. Overhead, Fame blows a trumpet, heralding the immortalizing power of the historians words.

The two-faced figure on the right recalls the Roman god Janus and is a personification of History itself. This signifies the link between past and future which is reinforced by the different ages of the faces. History gestures towards the entry to the museum, indicating that this place performs the historical function acted out by the allegories.

If history is the production of knowledge of the past, our familiar epistemological categories - bottom-up, top-down, and faith-based - apply here as well. The basic gathering of historical evidence is an empirical process, beginning with the most objective possible data. This is, of course, incomplete and decontextualized, requiring more abstract, interpretive structures to identify causal relationships and create classificatory systems. These higher-order interpretations then guide further inquiry but must be discarded when they fail to account for the factual evidence. The parallel with the scientific method and basic Aristotelian empiricism is not a coincidence; there is no other legitimate way for limited human points of view to explore a vast unknown. Metaphysical assumptions about history, like teleology or divine intervention, are not empirically verifiable or falsifiable, and correctly belong to faith.

No one will be surprised to see Postmodernism make a mess of this in the usual ways, ignoring empirical data and promoting baseless theories of human behavior on misdirected faith.

This fairy tale, another in an endless attempt to appropriate cultural achievements for a region with precious few, generated "heat" in academia, because intelligent people who know better are afraid of being called racist. On one side, we have a lack of material evidence, credulity towards myth that belongs in Chariots of the Gods, and inept philology; on the other, well, Bernal really wants it to be true. Ladies and gentlemen, Postmodern history.

The fundamental difference between historiography and Postmodern "historiography" is one of intention. The former seeks the most effective way to recount the past as truthfully as possible, while the latter defines "truth" as oppressive discourse and forces all findings into a predetermined conclusion.

Philosophical and historical errors combine in the absurd concept of secular transcendence, a series of lies intended to fool the credulous into believing that one could reject the supernatural ontologically, but still claim history follows a larger teleology or progress. In this way historians can become god-kings of a sort, in that they are privy to higher "truths" without any metaphysical standard to check their lust for power.

Incredibly, despite the countless lives lost and societies ruined, this sociopathic toxin still spews from academia, and probably will as long as the institutions prefer substandard credentialists to thinkers. Lacking the intellectual ability to assess sources critically and independently, it is inevitable that "scholars" will slavishly tie themselves to a well-known Philosopher's Name, no matter how debased.

Empirically speaking, history does not move by Hegelian dialectic, 19th century misconceptions about economics and teleology are not historiography, and "social class" is preceded developmentally by genetics and environment. The fact that Marx was a self-promoting scientific and historical illiterate is clear, but this does not excuse people today who follow his errors.

As with Postmodern epistemology in general, Postmodern history commits the category error of locating top-down transcendentals in the empirical world, where they are subject to evaluation. Of course, because they unknowingly accept these errors as articles of faith, cognitive dissonance and often aggression ensue. Were Postmodernists honest, they would abandon fictions like blank slate equality once they failed empirically, but they are more like doomsday cultists, pushing their demented faith despite all evidence of its destructiveness, until they collapse the system and are consumed in the aftermath. Christian historiography, makes for an interesting contrast, since it not strictly empirical, but locates the transcendent where it belongs.

Christ as Alpha and Omega, late 4th century, mural painting from the Catacombs of Commodilla, Rome

Remember that Christian ontology differed from Neoplatonism in positing a motivated and benevolent God as the ultimate reality. This means all time unfolds within God's plan for creation, a divine teleology from Genesis to Revelations. In this picture Christ, or God made visible, is flanked by the Greek letters alpha and omega, symbolizing the beginning and end of time.

In this system, individual history becomes oriented towards salvation rather than worldly fame.

The Christian historiography of the Middle Ages is set within Biblical creation, making it metaphysical and individualistic in focus.

The Good Shepherd, mid-3rd century, mural painting from the Catacomb of Callixtus, Rome

The earliest Christian images didn't depict Christ directly, but used symbolic images and figures to represent him. The Good Shepherd was an ancient pagan motif associated with protection that was converted to a symbol of Jesus.

Since Christ is God on an ontological level, we can combine the alpha and the omega from the picture above with the benevolent nature of the Good Shepherd to visualize Christian historical teleology. Like the One of the Neoplatonists, God is the transcendent source of everything, but unlike the One, He has a plan for creation that reflects His own ultimate goodness. This underlying divine motivation is often called providence.

Within this benevolent teleological structure, the only historical "dates" that matter are the Creation and Last Judgment, or beginning and end of the world, and the events around the life of Christ, which open the way to salvation. From a Christian perspective, this world is fallen as a result of Original Sin, which is a much more profound issue than snide criticisms of eating an apple would have it. Symbolically, the expulsion from Eden is a good metaphor for the loss of innocence through experience. But theologically, it represents turning away from the God's plan to follow one's own authority, and since God is ultimate reality this means choosing deluded pride over Truth. Satan is the template for the ontological self-erasure that comes from rejecting the nature of reality, and Adam and Eve recreate this error on a human level. Everything that follows their entry into the world is a consequence of this prideful blindness, and while Christ's sacrifice offers redemption on an individual level, even this is only realized after death. There is therefore no intrinsic value in the worldly accomplishments of fallen beings and fame and power are of no consequence for entry into heaven.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, The Tower of Babel, 1563, oil on panel, 114 x 155 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The story of the Tower of Babel, a human collaboration to reach heaven on their own was brought to an abrupt end by God. The lesson, as always, is that vain, finite human creatures cannot achieve transcendence on their own devices. It is a lesson that humans struggle with.

The Band is not the first to note the similarity between the Tower of Babel and the EU Parliament in Strasbourg. It appears this monument to human vanity will prove as successful as the prototype.

Worldly achievement is irrelevant in the face of divine teleology, but personal history becomes all-important. If the culmination of history is a final, metaphysical judgment, living the virtuous life necessary to secure a positive outcome is essential. This is not circumstantial; salvation is essentially open to anyone anywhere who accepts Christian doctrine on faith.

Hans Memling, The Last Judgment, 1467-71, National Museum, Gdańsk, Poland

The Last Judgment is the end or telos of Christian history, and it gives ultimate meaning to human life as well. Worldly achievement and fame means nothing here. To quote Matthew, "it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God" (Matthew 19:24, KJV).

There are two common forms of medieval historical writing that manage to fit within this structure, both of which are significantly different from modern notions of history: inspiring tales of saints and miracles, and chronicles. The former takes people and events out of their context to presents them as inspirational and behavioral role models. Chronicles record significant events in a chronological listing without interpretation of causality or deeper significance.

Twelfth-Century Chronicle page (f. 61), mid-12th century, with additions up to 1266, 25 x 16 cm, British Library, Harley 3775. The second part of this manuscript includes a chronicle history of central England from AD 1 to 1266 (ff. 61v-73)

A chronicle is an accounting of events year by year like a timeline. This one begins with the birth of Christ and moves forward to the time of the author. No lessons or interpretations are provided, because worldly events ultimately are meaningless in the overall scheme of things.

The chronicle histories of the Middle Ages can be thought of as a tale of years, or lists of dates and things that happened. The more ambitious ones incorporate early Biblical history and marvelous occurrences along with more current events, but all become focused on the local region as the chronology gets more recent. The European nations, with their distinct cultures, evolved organically out of the post-classical landscape around tribal and geographic identity. Christianity was the thread that gave them a shared affiliation. Chronicle historiography that recounts local events within a universal Christian context expresses this uniquely Western process of nation-forming. Since the the ebbs and flows of human societies are ultimately meaningless from teleological perspective, there is no interest in wider historiographic theory and interpretation. Of course, presenting things from a proto-nationalist point of view, or to legitimate a political structure, is a form of historical interpretation, it just isn't self-consciously theoretical.

Jean Fouquet, Coronation of Philippe Auguste in 1179, circa 1455, from the Grandes Chroniques de France, Paris, BNF Français 6465, f. 212v.

In this illumination, we see the connection between historical events (the coronation), French national identity (the royal heraldry of gold fleur-de-lys on blue field), and Christianity (the clergy crowns the king, representing God's sanction). The king, dressed in the same regalia as the setting, is the divinely ordained personification of the French people.

The Renaissance is far too large and significant a cultural and historical movement to attempt to sum up in a blog post, and historians are still trying to determine its full nature and scope. What we can do is identify some broad historiographic transformations that came out of the interest in ancient learning that characterized that period. But first, an important note on the relationship between the Renaissance and antiquity. It is a misconception, initially promoted to denigrate the intellectual achievements of the Middle Ages, that classical ideas disappeared altogether after the fall of the Western Empire. This falsehood has since allowed Postmodern "historians" to fabricate the myth that Europe was dependent on Muslim sources for ancient learning. Actual historians have noted "Renaissances" in the West since the time of Charlemagne (777-815). (Click for a good collection of artworks that show the transition from late antiquity to the Western, Byzantine, and Islamic medieval cultures). What is significant about the Italian Renaissance is the depth and intensity of focus on the language and culture of the ancient world, and the elevation of secular knowledge as an end in itself to the highest tier of Western epistemology.

Equestrian Statue of a Carolingian Emperor (perhaps Charlemagne's grandson, Charles the Bald), 9th century, bronze, Louvre, Paris

The bronze mounted emperor portrait was an ancient Roman symbol of honor and power. This figure is dressed in a medieval costume rather than a classical one, but the connotations of imperial authority are unmistakable, especially since this sort of image had not been seen since antiquity. By reviving this custom, the Carolingians defined their rule for posterity in terms of worldly classical glory. It is ironic that we are uncertain who this was, but unlike Postmodernists, we don't believe that the failure of a historical gesture to signify fully means that the gesture never happened.

The Italian Renaissance differed from earlier medieval interest in ancient ideas in depth and scope. In the bronze statue of the emperor above, the costume and style of the figure do not attempt to imitate classical models. The general Roman association between riding a horse and imperial power is sufficient to add meaning to what is basically an early medieval figure. In the Renaissance, the antique world became valued on its own terms, driving a sustained effort to revive classical language and culture in more historically accurate ways. It is not an exaggeration to claim that the modern historical disciplines - antiquarianism, archaeology, art history, philology, classics, comparative literature, historiography, etc. - have their roots in Renaissance interpretations of ancient sources. This movement, which transformed Western epistemology, is most commonly known as humanism, or Renaissance humanism, to distinguish it from secular humanism, its wackier modern cousin.

Sandro Botticelli, St. Augustine in his Study, 1480, fresco, 152 cm × 112 cm, Ognissanti, Florence

In this image, the famous Renaissance painter has reimagined the Father of the Western Church as a humanist scholar. His shelf is lined with the trappings of secular learning, including an orrery, manuscript of Euclidean geometry, and a clock. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Renaissance established an archetypal image of a scholar that defined Western academia until Modernity.

Note that there is no conflict between his learning and his faith. His bishop's miter is right by his elbow.

Humanist scholars first appear in fourteenth-century Italy, although the socio-economic roots of the movement are older. They got their name from their subject of study - the studia humanitatis or human-centered knowledge - which was more or less synonymous with ancient learning at the time. The term distinguished them from the Scholastic philosophers of the universities, and a large part of humanist self-representation, or branding, was in opposition to Thomistic medieval theology. The humanists were unequivocally Christian, but promoted Greco-Roman ideas as a guide to more virtuous living, ultimately giving antiquity a cultural authority that in hindsight was an act of unacknowledged faith. Whatever the motives, the Renaissance brought classical rhetoric and epistemology back into the center of Western thought, which from a historiographic perspective, meant ancient ideas about worldly achievement and immortality had to be accommodated to a Christian context.

Bernardo Rossellino, Tomb of Leonardo Bruni, 1444-47, marble, 610 cm, Santa Croce, Florence

Bruni was an eminent Florentine humanist, and his tomb mixes Classical and Christian values. His effigy and inscription indicate individual achievement and fame, while the Madonna and Child above confirm his faith in salvation.

Over time, fame and achievement became ends in themselves. It is difficult for the afterlife to compete with immediate rewards, given human time preferences and dopamine.

We can revisit the epistemology graphic from the previous post to visualize the broad outline of this union of Classical and Christian historiography. The distinction between empirical and top-down thinking will wait until the next post, when we tackle the errors and lies of Postmodernism more directly. It is, after all, necessary to understand a healthy physiology before excising a tumor. We can replace the three levels of reality with equivalent levels of history: personal, collective (national, cultural, world, etc.) and metaphysical. Supernatural forces like providence or any other teleology belong at the metaphysical level, beyond empirical validation, where they are accepted or rejected on faith. One cannot falsify the Creation, Incarnation, or Last Judgment, so they do not fit within historical standards of evidence. Classical history lacks teleology, so it focuses on the significance of human activity at the collective level. The two are really not compatible, but they do occupy different historiographic levels, and and can be made to coexist.

At the personal level, things get more complex. Both traditions place value on the outcomes of a personal history of virtue, only the virtues and outcomes reflect very different ethical systems. The ability to synthesize these (somewhere, Hegel is smiling) was a uniquely Western development, and critical for the innovations (and pitfalls) that followed. Classical fame and achievement in this world, tempered by a Christian historical teleology, provided the potential for a theoretical balance between the excesses of spiritual detachment and naked ambition.

Modifying the historiography graphic shows how classical and Christian ideas come together in the Renaissance:

By treating secular pagan knowledge as inherently worthwhile, the Renaissance opened the door to theoretical reflections on subjects that were not of interest to medieval thinkers. Classical historiography replaced the chronicle with interpretative narratives about the meaning of human history.

Leonardo Bruni, Historiae Florentini populi, late fifteenth century, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Pluteo 65.8, c. 1r.

Humanist Bruni's History of the Florentine People recounted the greatness of the Florentines and their role in cultural renewal, in a manner reminiscent of ancient Roman historians. The idea of celebrating the secular achievements and destiny of a people is foreign to the medieval chronicle tradition, and is a direct result of the Renaissance absorption of classical historiography.

Bruni also prepared manuscript histories of ancient subjects, such as the Punic Wars.