Beginning a three-post journey through beauty, logos, and the necessity of hope with Stephen R. Donaldson's epic fantasy The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever.

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

We aren’t sure if we can call it a regular category, but the Band has mentioned doing more positive posts from time to time. Looking for value in the brownfields of more recent popular culture. More recent than old thinkers and artists anyhow. The idea is to think through how some of the more abstract insights from the regular Band play out in general culture from after early 20th century Modernism settled down. Things that resonate today in some way other than the deep historical structural.

There are a few good reasons for this. The first is that it furthers our fundamental mission of promoting logos-based morality through truth and beauty. It’s one thing to point out that the system is inverted and fallen – it’s next level to share the kinds of pathways to the good that it lacks. Not just share either. Show how to find.

The Band is ultimately a personal journey, in that we are figuring things out as we go. We've come a ways, but there's always more. Like realizing someone has to rethink the art of the West... So we can't be too sure where we're headed

But along the way, we’ve realized readers have found us who value our process. That means that there is also value in showing how something as abstract as vertical logos is visible in the world around us. Like novels or movies.

We’ve never wanted to be anyone else’s visionary. We do want people to be able to see for themselves.

So – illustrate the abstract in concrete terms and in doing so, show others how to see the same. It’s why we always come back in some way to our concept of the ontological hierarchy. Not because we’re a myopic one-trick pony like that “black pill” movie retard. But because in the de-moralized, inverted, materialist illusion bubble that is today's beast system, a full view of reality needs constant reiteration.

The short form is that our discernment is inherently limited by our finite natures, and that what we can know about reality - ontology - and how we can know it are interrelated. May be time for a linked page, but seeing how long ordinary posts are taking... Well, here's the specifically Western-Christian version.

We first diagrammed it in non-religious terms by thinking through some basic things. But the inverse relationship - where the closer you come to the essential basis of things, the less materially clear our grasp of it becomes - is pure Christian metaphysics too.

Logos is a term used in the Gospel of John and ancient philosophy for the ordering creative principle that ties ontology together. Christians know the Logos as Jesus Christ, second hypostasis of the Trinity, God the Son, and the Word made Flesh.

But this is just our starting point. A rough diagram of how we seek truth based by only working from what we can know and how we can know it. The fun part is how each unique unique artistic expression of logos unfolds. At the level of ultimate reality, absolutes are One, and the Good, the Beautiful, and the True are synonymous. But we experience logos in the - imperfect - order in the reality around us and in in the beauty of our creative acts. We come closest to God - in whose Image we were created - when we fashioning the decaying stuff of an entropic universe into things of utility and beauty.

It’s not just an idea. We’ve written a couple of positive posts on works of more modern art – just without a linked page or announcement that they’re in a category. Thinking mainly of the ones on The Silmarillion and Dazed and Confused as examples.

Shout out to a young traditional artist working from Tolkien. They light the future.

The Silmarillion posts worked from two directions. They found the integration of vertical logos, ontological hierarchy, and the different epistemological modes [ways of knowing] we have to understand them perfectly illustrated. All in a gorgeous form that doesn’t just explain what material beauty is theoretically, it is it.

And this explains why The Silmarillion is so canonical.

Using the logos in a work of art to look into some wider truths is a great way to make abstract concepts visible to readers who prefer more concrete illustrations. It also shows how fluid and widely applicable these underlying ideas are. And that's a good way to share pattern recognition at work.

The Dazed and Confused posts let us explore Vox Day’s Socio-Sexual Hierarchy through the notion of verisimilitude. We refer to “realism” all the time on our arts of the West posts, but in a general “looks real in some way” way. These posts got us considering what it means for meaning in a more serious way.

Giving us a window into logos on the material level - the most diverse and hard to pin down. How do we determine what has value in modern beast culture? Like always. Look for what's true. The verisimilitude of the SSH is a tell that a social representation is truthful. It conforms to reality, so it's insights aren't subversive. Or inversive - a word that needs to exist as the subset of subversion that aims for total satanic inversion.

So that’s the positive category. It needs a name. We use the term “logos” a lot because it’s Biblical, it weaves together shades of meaning from our Christian and Classical roots, and accurately captures the unifying element in reality. At the same time, we aren't trying to make it our "thing". The word is too old with too much depth and too many high profile users over time. We'll keep using it because it's perfect for what it refers to. But it runs through all our efforts. It's not a category of post.

Felix Fossey, Allegory of Truth and Beauty, 19th century, private

Since we’re thinking about material manifestations of abstraction – how about the Good, the Beautiful, and the True?

It's a little to ponderous for a category, but closer to where we need to be. Since we are looking for truth in cultural expressions.

Finding Truth in Culture? Truth in Culture?

We’ll get back to you.

Whatever we call it, there are reasons for tackling more recent popular culture in a positive light. From the perspective of the Band's larger cultural project, it’s a way to get at the 20th century without having to make comprehensive claims. The 20th century is too recent, and the spray of disinformation too thick to sort out what we can know from the record. But the occult posts showed that bigger issues can be seen from little pieces.

The positive posts do too.

EKukanova, King of the Valinorian Noldor

Finarfin is the son of Finwe who rejects Feanor's satanic rebellion and becomes king. He reunites with his resurrected son Finrod in Valinor, but this shows him at Finrod’s Middle Earthly grave during the War of Wrath. It’s a meditation on the pointless suffering and waste that makes The Silmarillion so tragic.

The difference between the alpha making the right call over personal feelings and lesser ranks.

Dazed and Confused is a totally different context, but Randy is facing a version of the same alpha dilemma of which direction to choose. And his choice may have relatively similar stark consequences.

So options for more positive posts - things with logos - let us find universal threads in more recent culture while avoiding having to draw grand conclusions like periods on a timeline. That means we can’t just write on anything we like. Well we can, but then this already sprawling mass becomes incoherent. It would be easy to plug and play symbolism into vertical logos, but we want there to be some connection to larger issues too.

In The Chronicles, SSH verisimilitude overlaps with the ontological

hierarchy and the moral necessity of logos.

Another reason for positive posts is to explore logos on the material level. This is the most varied and contextual for obvious reasons and is best approached inductively, in a case-by-case way. Occasion to think about the interplay between the social-material forms like the SSH and the more abstract truths about the natural and moral direction of Creation is vaulable.

Ivan Shishkin, Noon in the Neighbourhood of Moscow, 1869, oil on canvas, private

This doesn’t mean Christian allegory, though Christianity is the ultimate foundation of Western metaphysics and morality.

Obviously it can be – it’s clear we’ll have to consider Narnia at some point if this continues as a series. But it has to conform to the natural moral order that reflects Christian Logos.

Consider.

Morality is the rational application of metaphysical truths to material contexts. Faith + logic + observation working in perfect synergy. Faith provides the moral foundation, observation the specifics in need of moralizing, and logic the moral reasoning to make the connection. The beauty of the ontological hierarchy as a concept is that it isn't a "system". It's a sketch diagram of how we exist in and know the world we inhabit.

Morality is the rational application of metaphysical truths to material contexts. Faith + logic + observation working in perfect synergy. Faith provides the moral foundation, observation the specifics in need of moralizing, and logic the moral reasoning to make the connection. The beauty of the ontological hierarchy as a concept is that it isn't a "system". It's a sketch diagram of how we exist in and know the world we inhabit.

Thisis what it looks like when we substitute the moral equation into the hierarchy diagram. It’s the same basic set of relations because the nature of reality doesn’t change.

What changes are the applicational relations of ultimate reality through logic to empirical, material, subjective situations.

Consistent relations stay consistent and we are referring to the most consistent of things - reality and our place in it. It's just true. So any scenario where we are dealing with multiple levels of reality coming together will follow the same pattern. Once you grasp it, it's a human constant. It's everywhere.

Take the concept of the arts of the West that we've worked out in our regular Band posts. The idea that art is like the Greek phronesis filtered through the cultural history of the West. An abstract mediation between higher truths rooted in ultimate reality and the ephemeral, changing world of experience relationship is the same pattern. It was introduced in this post and worked out over a few earlier roots of the West posts and probably best summed up in one called The Terms of Creation.

The application is different but the process is the same. This is extremely important because it sidesteps all the nebulous bleatings about art and free expression that plague even those who want art to be good and beautiful. The arts of the West are not free expression. Creativity is central, but creativity disciplined through technique and in the service of truth.

The reason for working this out becomes obvious when you put them together. This is why we talk about the arts of the West in a historical-philosophical way. It's also why we want to expand the search for logos to other areas. People need culture and the righteous will be more and more responsible for making their own going forward. Since the abandonment of truth and the related morality got us here, getting back to them seems prudent.

Of course diagrams understate practical differences. But that’s the point – when you’re looking for higher order similarities, to many empirical particulars are distracting. It’s why we need moral reasoning – otherwise there is no way to match foundational principles up with endless circumstances. And note our lack of convoluted rationalizations and procrustean adjustment.

Reality is consistent – in fact, a big liars’ tell is whether material claims contradict larger order patterns. If the Band is hard to read it’s because the concepts are inherently difficult or foreign and / or we’re not writing well. But there’s no deliberate fog or obfuscation. We keep jargon and new coinings to a minimum and explain them as best we can when they are necessary. And everything just… fits.

Since Logos is the lynchpin, cultural Christianity has to be our floor for positive post topics. Is it at the minimum conducive to a moral interpretation or does it throw up obstacles?

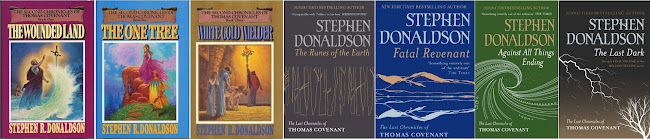

The Chronicles are so conducive to a reality-facing, logos-based, moral interpretation that they're worth multiple posts. It was a popular series with a lot of editions but that 1977 publication date might as well be 977, given the self-immolation of "mainstream" fantasy and scifi.

We aren’t going to summarize the books. We assume anyone interested in the analysis or intrigued by this introduction either has or will read them. And if you’re disinterested in The Chronicles but like to read the Band for the larger ideas, you won’t need to have read the books to follow and understand those. But unless you really dislike imaginative fiction as a genre, this is a set we recommend for any reality-facing physical library.

As hinted, we will be combining ideas from past positive posts. [note – we dislike alliteration. This just... happened].

Alberto Dal Lago, Elwing and Earendil

Subcreation and applicability from the Silmarillion posts

These are a pathway into how an imaginary place with the internal consistency of reality outlines truths in our world. And not only through direct symbolism or allegory. But in a general way, where situations in the story apply to things familiar to us.

Verisimilitude and the socio-sexual hierarchy (SSH) from the Dazed and Confused posts

These show how what looks irrational really isn’t when you understand human behavior patterns.

What we couldn’t really get into was how this connects to the moral order. Covenant makes way more sense when you realize he’s a foundering gamma. And combining them shows you the awesome consistency of truth and logos in the ontological hierarchy. Moving from gamma to delta on the social / material levels & finding logos in the metaphysical ones are the same process.

Francisco Goya, Truth, Time and History, oil on canvas, Nationalmuseum

Personifications can be an effective way of showing relationships. Truth is revealed in time. History records it for posterity. Cultural expressions of Logos are also higher metaphysical truths realized in time.

One is. And one is how we see it. Different manifestations of the same order of creation.

The truth or logos component of these positive posts corresponds to the episteme part of the art formula. It’s the higher truth or meaning. But lots of things do that. We also need something that

corresponds to the other end - techne. The actual material physical creation that expresses the higher truth.

It has to be good.

Ivan Aivazovsky, Ship on Stormy Seas, 1858, oil on canvas, private

Like a painting of clouds, light, and translucent seas by the master of water.

Giovanni Strazza, “The Veiled Virgin, 1850s, St. John's Newfoundland, Canada

Or a statue where the marble is carved into a translucent veil.

The craftwork. In the case of The Chronicles, the quality of the books - the writing, the plotting, the characters, even the experience of reading them, if we want to be as broad as possible. So positive work is morally sound and a really good read. Obviously the second is where the subjectivity that all art – all material-level perceptions – has comes in. Not everyone likes the things we do for purely personal aesthetic preference reasons. And this raises a problem for The Chronicles.

Consider the other works of fiction we’ve taken positive looks at. The Silmarillion is a pantheon-level literary creation and the Band’s choice for literary achievement of the 20th century. Dazed and Confused is less lofty an artistic achievement, but it is a masterful piece of movie-making and a beloved cult classic. The two are alike in that not many people who know about them dislike them.

Leather-bound Lord Foul's Bane from Easton Press for the bibliophiles.

A much higher percentage of people who are familiar with The Chronicles dislike them then the others. And while the Band thinks highly of them, we don’t have the usual blast for those that refuse to see our observations. Because this isn’t a category error, inversion, or falsehood. It’s subjective, and there are real reasons why the books might put you off that have to be dealt with.

So here’s where we’re coming from, then the problems with the book, then Lord Foul’s Bane as a set up for the integrated logos of The Chronicles.

Start by laying down a strong marker.

In the Band’s opinion, The Chronicles is the best work of fantasy not written by Tolkien or Lewis, and has particular moments and ways where it exceeds them both.

Note - we dislike having to differentiate “fantasy” from literature, but there is so much discourse around genre and convention that we feel it necessary to respect the traditional terms for clarity’s sake.

The Chronicles don’t have the depth of erudition or authorial craft to blast across entrenched discursive lines the way Tolkien does. But his imaginary world – the Land – achieves an intense sense of beauty and vitality that recalls the sublime landscapes and magic realism of painters like the American genius Bierstadt.

Albert Bierstadt, Mount Corcoran, oil on canvas, 1876, National Gallery

And that's a good thing for us. We rely heavily on visuals to make our points and there aren't that many pictures of Donaldson's works. Tolkien is one of the most illustrated authors in any tradition of all time, with hundreds of quality pictures to choose from. The Silmarillion posts were full of things from professional paintings to inspired fan art. Dazed and Confused is a movie. When we did our close watch to take notes, we were pausing and going back constantly. Getting all the screen grabs we needed was easy. This post will rely less on direct illustrations and more on pictures as a parallel "text" of sorts that builds the arguments. Like they do in the philosophical posts, but with an eye on visually fitting the story too. That's why it's taken so long to put this together.

Tolkien raises the most obvious comparison The Chronicles - The Lord of the Rings. Here’s a signed first edition for a little over 60 k. Christmas is just around the corner...

A trilogy revolving around a magic ring at a time when the 70's wave of

Tolkien-inspired, D&D powered fantasy was cresting would be enough.

But there are also enough similarities between names and plot structure

– especially in Lord Foul’s Bane – to be noticeable.

It’s not the shameless rip-off that is The Sword of Shanarra. Seen here in collector's leather. It appears that Easton had a Tolkien boom series.

The similarities are deceiving because it’s actually very different in tone and style. And nary a village boy chosen one to be found. Our take is that Donaldson - who insists he wasn't responding directly to Tolkien - was using familiar features as a shortcut for world-building. You more or less know where you are, so he can get the story moving and fill in details as needed along the way. The story then upends a lot of the conventions that were already becoming flaccid tropes in Tolkien’s less-talented wake. Mysterious strangers guiding rustic dolts on world-saving McGuffinQuestsᵀᴹ and so forth. But not in a subversive, postmodern snarky hack way. To tell a story where the same Logos shines through a different lens. Forget snark - The Chronicles's intensity has a relentless pressure that exceeds Tolkien and compensates for some limitations in the writing.

Tl;dr – it takes familiar conventions, spins them in unique and powerful ways, and expresses deeper logos.

Allan Morris, Questers

Morris is one artist that is representing scenes from Lord Foul's Bane, and we will promote his work here. There just isn’t enough of it to build posts around it like the other two. Click for the link to this painting and the rest of his Lord Foul's Bane portfolio.

Conventions like the Quest to the Mines of Mt. Doom through tree-town dwellers, evil monsters, and the horse people of the plains. There's lots of action and fantastic scenes, a lot gets filled in, and the pages keep turning. Donaldson's gift for memorable scenes is a big part of this.

Conventions like the Quest to the Mines of Mt. Doom through tree-town dwellers, evil monsters, and the horse people of the plains. There's lots of action and fantastic scenes, a lot gets filled in, and the pages keep turning. Donaldson's gift for memorable scenes is a big part of this.

There’s lots of action and fantastic scenes and beasts, and the depravity of the enemy is made viscerally clear. This is a big difference from Tolkien, whose meditation on evil is a little more abstract.

Donaldson looks very closely into the nature of evil operating on different levels. His morality aligns with Tolkien – despair is the enemy, evil can only corrupt and pervert – because both are built on underlying logos. But Donaldson looks at his evil more up-close. It’s not the sado-porn villain fetish that you see in a lot on modern imaginative fiction...

Rape Rape is the low hanging fruit - pity the poor branch! But he's far from the only modern fantasy writer using the genre as an excuse to wallow in depravity and horror, with minimal heroic imagination or commensurate payoff at the end.

But you are given a more immediate sense of atrocity that Tolkien spares. And a more immediate sense of how it echoes through time.

The Chronicles recognize HOW the spiritual, intellectual, and

physical onslaughts of evil are linked.

It’s easy to say "don’t give into despair", but Foul combines his psychic onslaught with overwhelming force. The despair comes when defeat means horror beyond imagining for all Creation and is also more and more inevitable as hope dies slowly. We are told of the mighty Lord Kevin [note - ignore the names. They're an Achilles heel of Donaldson's] who succumbs to despair after having his friends and associates slaughtered, his armies crushed, the endless ravishment and torture of the Land he loved underway, and his own personal defeat.

Every path out was systematically taken from him. His fate was to be captive witness to an orgy of atrocity leading to extinction while Foul jeers and revels. There no way to see or think his way out. All material and rational pathways seem closed. The result is the Ritual of Desecration - Kevin's murder-suicide of the Land in a failed last hope of killing Foul.

Every path out was systematically taken from him. His fate was to be captive witness to an orgy of atrocity leading to extinction while Foul jeers and revels. There no way to see or think his way out. All material and rational pathways seem closed. The result is the Ritual of Desecration - Kevin's murder-suicide of the Land in a failed last hope of killing Foul.

Evan Johnsen, Desolation, 21st century, ink and watercolor on paper

And here's Covenant's vision of the Ritual of Desecration.

Behind the luminous morning, he saw hills ripped barren, soil blasted, rank water trickling through vile fens in the riverbed, and over it all a thick gloom of silence-no birds, no insects, no animals, no people, nothing living to raise one leaf or hum or growl or finger against the damage.

Lena tells Covenant that this her people survived the conflagration by taking to the mountains where they remained for centuries. They only returned to the Land he sees now twelve generations ago - a blink of an eye by historical standards. The difference in the perspectives of immortal evil and finite limited humans is made stark.

To the people, centuries passed after the great cataclysm before they carefully made their way out of their mountain exile. The old order - surviving only in history and legend - is gone. Even Foul appears blasted out of existence. Then twelve generations is a long time too. Like colonial times to us. So the long process of recovery that gets underway sees itself as a new age, with Lords and Foul ancient history.

To Foul, it's a pause.

Foul differs from Satan in that he takes material form and acts like a god from mythology on the world physically. He participates in the Ritual knowing his immortal essence was safe from real harm, looking to serve Kevin a final exploding cigar.

But the unexpected power released blew through his defenses, vaporized his body, and so reduced him that it took centuries to even start to reconstitute. He indicates that it was a terrible experience, adding even more fuel to his rage and hate.

There's no new age for Foul - just the resumption of his immortal war after recovering from a setback. And it's hard to imagine the likes of Lena's naive Oath of Peace huffing Whoville of a village rising to the level of speedbump to Foul. Hence the necessity of faith in something greater than human powers of resistance.

Take Atiaran in Chapter 8 - "But you do not have the stink of a servant of the Gray Slayer. My heart tells me that it is the fate of the Land to put faith in you, for good or ill." Or High Lord Prothall in Chapter 13 - "Be of good heart, Rockbrothers. Your faith is precious above all things".

Is this explicitly Christian faith? No - the Land isn't a specifically Christian allegory. But if there is one thing we can say about Donaldson the writer, it's that he is conscious of his language. And faith refers to a way of understanding reality. One that is applicable to the necessity of Christian logos in our world.

Is this explicitly Christian faith? No - the Land isn't a specifically Christian allegory. But if there is one thing we can say about Donaldson the writer, it's that he is conscious of his language. And faith refers to a way of understanding reality. One that is applicable to the necessity of Christian logos in our world.

Jonathan Lipton, Faith, Hope and Charity, 2015, oil on canvas, Springville Museum of Art

Faith is not hope. The two are both classic Christian virtues – charity was the third. The Band has explained ad nauseum how faith is how we know the highest ontological level – ultimate reality or God and His will. It is as certain as any other form of knowing – more certain, since it deals with the most fundamental Truths and is therefore the foundation of the other modes.

Consider Foamfollower's dialogue with Covenant...

What value has power at all if it is not power over death? If you place hope on anything less, then your hope may mislead you.SO?But the power over death is a delusion. There cannot be life without death.All right. So you're right. Tell me, just where the hell do you get hope?From faith.

This is how The Chronicles points to the necessity of Logos without Christian allegory. Over and over we see the ultimate uselessness of human activity - even logical human activity - without an anchoring in ultimate reality. It fails without faith and hope. And why are they necessary? Or better yet, what is Foul that makes faith a requirement to defeat him? Start with another key point - something The Chronicles shares with The Silmarillion though in different ways.

The Land externalizes relationships that are immaterial in our world.

Consider Foul as an especially tangible representation of the Fallen nature of the Land. Like Satan, only externalized by the Land as a physical entity as well. Both of them are the architect and the archetype of evil in their realities. Foul's rebellion against the Creator introduced evil into Creation as an antithesis to divine order and he himself is trapped in the temporal world as an entity. Donaldson uses the concept of “banes”- items of immense evil buried in the Land - to represent the less personal aspects of a Fallen world.

"Here is the Land," Mhoram whispered. "Grim, powerful Mount Thunder above us. The darkest banes and secrets of the Earth in the catacombs beneath our feet. The battleground behind. Sarangrave Flat below. And there-priceless Andelain, the beauty of life. Yes. This is the heart of the Land." He stood reverently, as if he felt himself to be in an august presence. Chapter 21

An inherently beautiful and glorious creation marred by primordeal evil

and a satanic overlord is a pretty good metaphor for the pre-Christian

world.

The stories of the mighty Old Lords and their destruction by Foul reinforce the message of human limits in the face of immortal evil in a fallen world. Kevin didn’t seek the conflict - he and his followers turned the Land into paradise. Didn't matter. Foul came with subterfuge, treachery, then open war. Evil was born in an act of willful opposition to the Good. It's always coming. And faith in flawed human paradises on earth are doomed to fail. Kevin’s Desecration just makes it dramatic. But he's not the first of Foul's victims. The first of the Old Lords and Covenant's avatar Berek Halfhand also finds himself facing the end of all.

Alas for the Earth. We are overthrown, and have no friend

to redeem us. Beauty shall pass utterly from the Land

Berek is delivered by the Earthpower - the active power for life and health within the world and the way the Land extenralizes the glory of Greation. The great Fire-Lions that destroy Berek's enemies are a Chekov's gun.This painting shows the Fire Lions at the end of Lord Foul's Bane miraculously delivering the party.

Covenant is looking rather like a Christ figure here.

Michael Whelan, The Eagles are Coming, 1978, acrylic on canvas

And yes, escaping thethe fatal lava on an outcropping is another Tolkienism. These are the little things that undermine the book. It wouldn't have been hard to find a different cliffhanger. Maybe involving a cliff?

Note the language that follows.

We are told that Berek uses his Earthpower to fashion something called the Staff of Law to began healing the Land. We are never really explained what the Staff is and why it gives such power over natural things. In the story it is a powerful tool for the protection - or perverson in the wrong hands - of the Land. But the use of Law to reference the natural order or Logos of his world is an interesting word choice. Neither chaos, disorder, or like word is used for evil.

Law refers to moral absolutes - especially when we think of Berek as the forerunner of Covenant. Consider the name "Covenant" for pete's sake. Donaldson is teeing up one of those typological relationships that theologians used to tie the Old and New Testaments of the Bible together. The Law of Moses superseded by the New Covenant with Jesus.

With Foul in a Satan role and Berek-Covenant applicable to different expressions of God in the world, things start to take form. and we see the same problem in both places.

"Alas! thus the Despiser was emprisoned within Time. And thus the Creator's creation became the Despiser's world, to torment as he chose. For the very Law of Time, the principle of power which made the arch possible, worked to preserve Lord Foul, as we now call him. That Law requires that no act may be undone. Desecration may not be undone-defilement may not be recanted. It may be survived or healed, but not denied. Therefore Lord Foul has afflicted the Earth, and the Creator cannot stop him-for it was the Creator's act which placed Despite here."In sorrow and humility, the Creator saw what he had done. So that the plight of the Earth would not be utterly without hope, he sought to help his creation in indirect ways. He guided the Lord-Fatherer to the fashioning of the Staff of Lawa weapon against Despite. But the very Law of the Earth's creation permits nothing more. If the Creator were to silence Lord Foul, that act would destroy Time-and then the Despiser would be free in infinity again, free to make whatever befoulments he desired."

The Staff of Law - like the Tablets of Law - is a sendings from God to help mitigate the effects of the fallen world that prove woefully inadequate. The problem is that Law of any kind requires unchanging, timeless, absolute standards and perspectives that are impossible for fallen, temporal, subjective, limited humans. Is it that hard to see the applicability of the Creator founding a Covenant by speaking to Berek through Fire-lions on Mount Thunder and God doing the same with Moses through a Burning Bush on Mt. Sinai?

It's the same problem over and over - good old secular transcendence. That finite, fallen, temporally contingent, subjective minds can perceive - let alone conform to - the ontological absolutes qua absolutes of an eternal God. That’s a mouthful, but we need to be precise with the wording. It’s a fundamental flaw that can’t be overcome. The decision to build the Modern West on it is why the fake post-Enlightenment system is collapsing.

It’s not an ideological opinion. It’s mathematical. The easiest way to

think of it is trying to put infinite water in a finite bucket.

Overflowing bucket from Beatrix Potter's Mrs. Tiggywinkle

No matter how great our capacity, we can't grasp it all. So to maintain any kind of moral consistency over time, external standards are needed.

And it goes the other way.

Foul is a higher-order being trapped in what is literally called the Arch of Time. The temporal nature that divides Donaldson's and our material worlds from eternal abstracts. Like Foul.

Change and imperfection are as traumatic and alien to him as conforming to absolute truth is to us. His misery at being trapped in this lower realm of change and time drives his sadistic rage. More on his home in the The Power that Preserves – for now we will just point out the contrast between the endless richness of the giant-carved Lord’s Keep and the flawless inhuman perfection of his Foul’s Creche.

Donaldson also catches the difference between abstract and ultimate reality. Foul doesn’t dissolve into the world like Morgoth, but he is equally tormented by his inability to create. His armies are either already-existing allies or things he warps and perverts.

Drool is a cavewight – a strong, subterranean race that generally serves Foul. Mortal flesh and blood. He’s the immediate threat in Lord Foul's Bane, though Foul orchestrates his clash with the Lords for his own ends.

The first point is that manipulating abstract powers are too much for him, and by the end of the book, his form is twisted and gnarled.

The scenario is typical of Foul and Donaldson’s understanding of the mechanics of evil. Foul creates no-win situations that turn your attractions and loves against you. The harder you strive against an unbeatable foe, the more painful and brutal the fall.

Take the prophecy he sends to the Lords.

Take the prophecy he sends to the Lords.

I’m going to smash you in 49 years but I need you to take out Drool. If you don’t, you’ll be dead in a few. If you do, I’ll gain the means to destroy you in a way that slowly and inexorably grinds forward exactly as predicted. But it’s more than maxing out the despair. Foul’s an abstract-level being – his terms and metrics are radically different from finite, material ones. He isn’t fighting to live or die – his battle is with hope.

From Foul’s perspective, mortals are all dying either way. He would prefer to maximize the suffering, and his own power seems tied to intangibles in some way – true mirth is fatal to him in the end. Mortals are fighting to live – they don’t understand the moral or metaphysical level that the conflict is taking place on. And so we have no way to withstand the fallen nature of the world on our own in the end.

From Foul’s perspective, mortals are all dying either way. He would prefer to maximize the suffering, and his own power seems tied to intangibles in some way – true mirth is fatal to him in the end. Mortals are fighting to live – they don’t understand the moral or metaphysical level that the conflict is taking place on. And so we have no way to withstand the fallen nature of the world on our own in the end.

The Angel of History presides over the end of material things. The Judgment awaits.

The path in the prophecy that gives them the greatest hope for survival - the most time to try and counter Foul - also most prolongs the fear and suffering. On the psycho-spiritual levels, the game is whether he can break them before he kills them. We said Donaldson's evil is nasty. What better way to clarify what is really at stake in a world where its true face is hidden?

The extreme power imbalance between Foul and the people of the Land makes the cause hopeless. This is realistic. The Land makes intangibles visible to us. Applicability. The Prince of this World is invincible to Fallen creatures down here on their own. The Law is no more able to stop Foul in the Land than it can stop falling away from God’s covenant here.

Those are absolutes. We’re finite and fallen. Us taking on immortal evil in the Valley of Death is secular transcendence from the other end and doomed to fail. Just like Enlightenment Rationalism, Hermeticism, Gnosticism, post-Modernism, techno-literally-no-one-cares-ism, and every other infantile “be your own god” vanity play that is a sign of our fallen natures.

Yet Donaldson insists on the necessity of hope throughout the series and delivers it in the end. How does one hope in the face of that? Foul's whole game is driving the righteous to extravagant hope before systematically and violently crushing it by increments. What can counter this degree of ingrained evil? Externally - in the Land, where Foul just steamrolls everyone - or internally - here - where we steamroll ourselves?

Gustave Doré, The Triumph Of Christianity Over Paganism, 1868, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Canada

Yeah.

The bigger steamroller gets us to the savior/chosen one dimension to The Chronicles. Covenant is the instrument of the Creator – think ultimate reality – and therefore wields power outside Law and beyond Foul. He isn’t Incarnate in the same way as Jesus and is morally pretty clost to opposite of Jesus. Applicability not allegory. It’s partly how he operates outside the metaphysical hierarchy, confronts the same moral problems as the Land on a different level, and mops Foul’s Creche with him when finally sufficiently together.

Consider the white gold that is the source of his limitless power. Again, not the equivalent to Jesus, but another impossible paradox arising from bridging ultimate and material reality in an entity. A logos that exists outside time, bridges realities, empowers life, and exceeds all conceptual limits or standards...

And note how Lord Mhoram’s understanding brings unflinching faith in Covenant. And how that is rewarded with deliverance beyond expectation and a power through which all things are possible in the aptly named The Power that Preserves.

The relationship with Berek-Moses and the Old Covenant of the Law is even typological! And that name...

Here's a good picture of the typological connection with Berek. The picture of the Old Lord-Fatherer - it's a tapestry in the story but looks more like a painting here and the present day Covenant. The Law foreshadows Grace.

Of course Covenant isn’t an Incarnate God – he has his own story of growth and conflict. Much of the depth of the story comes from the different perspectives in the two plotlines – the people of the Land’s view of Covenant and his own view of himself. He has to grow and find the path to logos before he can hope to face Foul directly. And that means overcoming his trainwreck nature.

Part of Covenant’s problem is his moral relativism. He’s a good piece of modern protoplasm that way. Another thing The Chronicles does really well is make clear the uselessness of moral relativism and other secularist fairy tales in the face of real evil. It’s actually the existence of evil that starts breaking through TC’s shell. But he has a way to go, and in each book, another avenue of cowardly escape is shut down.

Hold that thought.

Allen Morris, Ranyhyn

The Earthpowered horses are one of Donaldson's creations that never seemed to reach their potential interest. As an expression of the Land - almost it's conscience - they have a difficult relationship with Covenant. They are both compelled by his ring and terrified of him.

In Lord Foul's Bane they are the recipient of the first of Covenant's "bargains". Deals he makes with himself to avoid facing responsibility or even agenct in a Land that he can't accept as real and can't deny as false. It ends as well as you'd expect such a bargain to.

Covenant's bargains are important. They just aren't as clear as they could be. His initial strategy for dealing with the impossible madness of the Land is to Disbelieve - it becomes his title. But the reality of the Land is too insistant to deny - too beautiful, the evil too evident - and he becomes trapped. The need and impossibility of disbelief are a paradox, like the white gold. Like the Incarnation in reality. He can't square the circle and the first bargain is a way to avoid taking any action at all. This way he can avoid any responsibility, blame, or even need to settle on what the Land is.

He needs to learn that in a fallen world where evil is an active presence not choosing is a choice.

Listen. I'll make a bargain with you. Get it right. Hellfire! Get it right. A bargain. Listen. I can't stand-I'm falling apart. Apart." He clenched Pietten. "I see-I see what's happening to you. You're afraid. You're afraid of me. You think I'm some kind of- All right. You're free. I don't choose any of you."

"But you've got to do things for me. You've got to back off!" That wail almost took the last of his strength. "You-the Land-" he panted, pleaded, Let me be! "Don't ask so much." But he knew that he needed something more from them in return for his forbearance, something more than their willingness to suffer his Unbelief.

"Listen-listen. If I need you, you had better come. So that I don't have to be a hero. Get it right."

Lena! "A girl. She lives in Mithil Stonedown. Daughter of Trell and Atiaran. I want-I want one of you to go to her. Tonight. And every year. At the last full moon before the middle of spring. Ranyhyn are what she dreams about" (Chapter 19)

His extremity of emotion comes from having killed five cavewights during an attack on the party when his ring fired up. His response is a vow to do nothing so as to escape any future responsibility. This is the danger in moral relativism. Because he has no connection to larger truth or logos, he is incapable of seeing the difference between defense and attack. Or when righteous war is needed. He's a de-moralized solipsistic pussy, so all he can do is whimper to himself about having helped defend everyone and then vow total passivity and avoidance of any responsibility at all.

He is incapable of moral distinction because can’t think past his own feelings at the bigger picture. A moral imbecile at this point, drunk on self-pity. Hence the bargain. And when this predictably fails, TC’s trauma completes the logos message for the first volume. In Five applicable logos message steps

John Martin, Satan Presiding at the Infernal Council, 1824, engraving, Victoria and Albert Museum

1. The world is intrinsically Fallen and ruled by an evil god.

Maxfield Parrish, Swiftwater (Misty-Morn), oil on canvas, 20th century

2. The inherent goodness of Creation is expressed in beauty.

The Land radiates health with a richness beyond our perception.

3. Moral relativism becomes immoral if

evil exists

Evil is by nature aggressive and expansive. Not actively choosing good is abetting evil by default.

4. But we are insufficient to use # 2 to overcome # 1 on our own.

The Fall is ontologically beyond us

Yongsung Kim, Drink and Never Thirst

5. All signs point to the necessity of faith in divine salvation.

"All right. So you're right. Tell me, just where the hell do you get hope?"

From faith.

The vaguely Biblical feel here extends beyond the Covenant as savior story. The way that the geography seems imperfectly resolved beyond what is needed for the narrative. There's references to places, but how the Land fits with it's wider world is left blank. The difference is that the Bible is understated and allusive rather than keeping the tension cranked. But the similarity tells us that the focus is on events and people over settings. Actions over beguiling places. Plot and logos.

It's a pretty standard start of a fantasy book map. Enough to show you where things are relative to each other and to follow the events. We start in Mithil Stonedown, journey to Revelstone, then wind up under MountThunder. We knlow there are lands beyond - the Giants come from oversea, the Bloodguard from beyond the Western Mountains, and the peoples of the Land survive the Desolation in exile. But little is said of these places, and given Foul's presence, the Land often seems like a whole world in itself.

The downside is that the Land can seem almost claustrophobic at times.

Consider - Covenant can be tracked by his alien boots hitting the ground. And he insists on wearing them despite the pain it causes for reasons that make little sense – even given his established psychological limits. Characters acting in irrational ways within the story to advance the plot is one of Donaldson's limitations. It becomes terminal in the subsequent sequels that were never written and it is visible here.

Consider - Covenant can be tracked by his alien boots hitting the ground. And he insists on wearing them despite the pain it causes for reasons that make little sense – even given his established psychological limits. Characters acting in irrational ways within the story to advance the plot is one of Donaldson's limitations. It becomes terminal in the subsequent sequels that were never written and it is visible here.

There are times when the journey has the sequence of encounters feel of a D&D DM winging it. Move, talk, fight, move, talk fight. It's not the meaningless blender of the later works, but a beguiling path is a path all the same.

Having the enemy constantly hanging over the hero fails in later sequels because Donaldson had no plot and was throwing as much stuff as he could at the wall. Here there is more of a balance. Either you find it effective at turning pages or not. And if you do, Covenant’s psychodramas, dishonesty, and overall pathological intransigence turn the conventional quest into a different type of experience. But one that isn’t ironic or parodic. If it’s subversive it’s because it’s familiar yet different.

Having the enemy constantly hanging over the hero fails in later sequels because Donaldson had no plot and was throwing as much stuff as he could at the wall. Here there is more of a balance. Either you find it effective at turning pages or not. And if you do, Covenant’s psychodramas, dishonesty, and overall pathological intransigence turn the conventional quest into a different type of experience. But one that isn’t ironic or parodic. If it’s subversive it’s because it’s familiar yet different.

The feel of constant menace also covers for the exposition. Information-packed dialog doesn’t drag because it’s filling in curiosity between rounds of action. And something always attacks. Donaldson even manages to make you want to know more about his world. You know exposition had been successfully pulled off when the reader wouln’t mind a little more.

Donaldson never world-built like Tolkien. No one did, but the Land isn’t that well fleshed out compared to epic fantasy in general. The intense language, pacing, themes, and shifts makes the work way more magnetic than you would think possible given his technical limits. If you like The Chronicles, they are exhausting. That may even be the key – especially when we think of Donaldson's incredible cathartic conclusions. There is something of the Greek tragedy here as well as the Biblical – in a way that we don’t see in Tolkien.

Henry Fuseli, Oedipus Cursing His Son, Polynices, 1786, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art

Not obviously – The Chronicles are epic fantasy and epic is by definition different from tragedy in classical theory. Epic is wide-ranging, vast – like the adjective suggests. Tragedy has laser focus on the main plot. What’s similar is the way tragedy combines lurid intensity and a setting that isn’t more fleshed out than needed. Because the emotional impacts are similar – intense wringer leading to revelatory catharsis.

Not obviously – The Chronicles are epic fantasy and epic is by definition different from tragedy in classical theory. Epic is wide-ranging, vast – like the adjective suggests. Tragedy has laser focus on the main plot. What’s similar is the way tragedy combines lurid intensity and a setting that isn’t more fleshed out than needed. Because the emotional impacts are similar – intense wringer leading to revelatory catharsis.

Ultimately the overall trilogy falls short of the The Lord of the Rings’s plateau. Which is fair – that one is the Band’s choice of best book or novel of the 20th century. Donaldson is a less gifted writer, as his subsequent output confirms. This is the best thing he wrote by a wide margin. Again, which is fair. Number four on our all time fantasy list - after The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion and the Narnia series – by a much less talented writer - leaves little room for realistic improvement.

But what makes it hard to classify isn’t just that there’s an unevenness that it’s lofty peers lack. It’s that it attains this level despite this unevenness because the peaks are so extravagantly, impossibly mind-blowing.

What are The Chronicle's strengths? Why read them?

Structure, and plot to a degree – the structure of the story is where the logos shines through, both metaphysically and personally. Differentiating this from the plot is a bit forced, but we wanted to make it account for the limitations in the storytelling and the logos that runs through the whole thing. That said, the book is a page turner, without any significant inconsistencies.

Alberto Prosdocimi, The Lake Steps, Spring, 19th century, oil on canvas, private

Imagery - Donaldson invests the Land with a haunting reality despite it's geographic uncertainties that doesn’t quite reach Lewis’ all-time iconic image-making but is in the neighborhood.

Intensity - constant mounting pressure with increasingly frequent bursts of danger, horrifying doom, and epic catharsis that surpasses Tolkien on a purely emotional level. A purely, satisfyingly, appropriate climax and conclusion on the level of Watership Down but with a longer sustained build of tension and pressure building up to it.

Antonio Gaudi, Roof of Casa Batlló, 1904-1906, Barcelona

There is something of Gaudi in The Chronicles. They're a uniquely engaging rhetorical roller-coaster that falls short of classical in the genre perfection but… who cares!!

What they accomplish wouldn't be improved by fixing the ideosyncrasies. You either like it or you don't.

Covenant’s subplot is a gamma learning to accept truth. This unfolds progressively over all three books – his growth in logos is a huge factor in rating the books as highly as we do. Characters that grow and change is one measure of strong writing, and Covenant does that. But it means that our grades for the three books are quite different if we separate them from the bigger story.

Allen Morris, Lord Foul's Bane

Start with Covenant at rock bottom morally and personally. Nothing clear about this world yet. The most conventional quest-based storyline of the trilogy, which does keep the pages turning and the intensity up as the audience gets up to speed. But still - journey to Rivendell, council, the fellowship’s journey to Moria/Mt. Doom/caves hangs in the air.

And there’s having to deal with all the all the weirdness of Donaldson’s language without having gotten invested in the story. A lot of stuff that is pays off for the larger arc, but it can be a bit of a drag at times on it’s own.

Our Grades

That’s our marker. Now for the problems.

The first is the language. Donaldson writes in an odd and mannered way with lots of deliberately obscure words and strange analogies. It’s not as willfuly cryptic as Gene Wolfe, but some find it off-putting. It’s especially the case with his descriptors – adjectives, adverbs, similes, metaphors, etc – that pile up visceral emotionally-charged associations.

Here's a quote from Chapter 1.

Dangers crowded through it to get at him, terrible dangers swam in the air toward him, screaming like vultures. And among them, looking toward him through the screams, there were eyes-two eyes like fangs, carious and deadly. They regarded him with a fixed, cold and hungry malice, focused on him as if he and he alone were the carrion they craved. Malevolence dripped from them like venom. For that moment, he quavered in the grasp of an inexplicable fear.

It struck the company with radiated malice. The hawk was ill, incondign, a thing created by wrong for purposes of wrong-bent away from its birth by a power that dared to warp nature. The sight stuck in Covenant's throat, made him want to retch. He could hardly hear Prothall say, "This is the work of the Illearth Stone. How could the Staff of Law perform such a crime, such an outrage? Ah, my friends, this is the outcome of our enemy. Look closely. It is a mercy to take such creatures out of life." Abruptly, the High Lord turned away, burdened by his new knowledge.

Norman Rockwell, Boy Reading of Adventure, 20th century

Reading for pleasure is supposed to be enjoyable. It's in the name. If the wording of a book is annoying, don’t read it. Plenty of logos to be found elsewhere.

The young Band found The Chronicles to be a roller-coaster. But one that stayed with us and deepened over time. That's always a good sign.

Our take on the language is that it’s an effective way to add a page-turning element that papers over some of Donaldson's limits as a writer. The off and highly intense wording piles up like a rhetorical backbeat that adds emotional shading to everything. The mood is transitive – how you react to things that you encounter in the story is conditioned by this larger atmosphere. It's rhetorical because it's a veneer. Atmosphere from the diction and not the plot.

Then there’s the more serious issue of Covenant being an awful person to spend time with. On just about every level. Start with the leprosy.

X-ray showing primary periosteal reaction in 1st metatarsal, ice-candy appearance in 5th metatarsal and soft tissue changes in a leprosy sufferer.

Just typing it drives home the point like a Raver’s iron spike. The endless references and lurid descriptions are part of the intense language and unpleasant reading. And the psychological and physical limits it puts on him makes him less effective as a hero. He’s actually that most annoying sort of a-hole – the one with a legitimate problem that makes it hard to just unload on them like they deserve, but doesn’t actually justify their a-hollery.

Just typing it drives home the point like a Raver’s iron spike. The endless references and lurid descriptions are part of the intense language and unpleasant reading. And the psychological and physical limits it puts on him makes him less effective as a hero. He’s actually that most annoying sort of a-hole – the one with a legitimate problem that makes it hard to just unload on them like they deserve, but doesn’t actually justify their a-hollery.

Leading to the rape near the beginning of Lord Foul's Bane. It’s certainly not extreme by the sado-porn standards of modern fantasy, but it’s very blunt and disturbing in context. And it caps an already unlikable TC. Not hard to see why some check out. We nod our heads. It’s a flawed book.

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853, oil on canvas, Tate Britain

Pre-Raphaelite master's take on a kept woman awakening spiritually. That's the beauty of the Good News and the benelovance of the Logos. It's never too late to accept the offer.

Covenant's unpleasantness makes his journey to logos more powerful as a lesson. It does make him hard going in the early stages.

In terms of applicability, Covenant's journey from walking dead to living human with a fighting chance traces a pattern of Christian awakening in a non-Christian sub-creation. And this means overlapping moral frameworks. And it takes place on different levels at once. Remember that the Land externalizes intangibles. It's black and white, good and evil. The moral polarity that we can't see directly in our world – Christian duality – is a visible, tangible, crystalline fact.

What shakes out can be described as two levels of “evil"

The first is the Passive Path. Covenant would consider himself a reasonably moral person in the way most moderns do. Lives and lets live, pays his taxes, etc. The way he is described in the early chapters shows a guy who most people might admit has problems but isn’t a “bad guy” in any clear way. Just an unlucky victim of modern society. But given the right mix of stressors and circumstances, his “disbelief” provides cover for psychopathic indifference and rape.

Passive Evil

Not having the opportunity to fail a test of virtue != virtuousness.

The deleterious effects of the fallen world - moral entropy, shame-based morality, de-moralization are the petrie dish of passive evil.

The Active Path is what we think of as conventional villainy. Deliberate malevolence.

Franz Stuck, Lucifer, 1890, oil on canvas, National Gallery for Foreign Art, Sofia

Active Evil

Foul is actively sadistic. He initiates conflict purely to harm and destroy – the embodiment of willful evil in the universe.

It’s easy to dismiss active and passive evil as radically different – so different as to be totally separate character types. What The Chronicles does is show the deeper connection between them despite the appearance of difference.

The frame of reference is a big part. Covenant’s world is ours of a few decades ago. A materialist flatland of secular transcendence where most smugly reject entities like Foul. Many even argue that there is no “evil” – just illness and/or trauma. Because there is no logos beyond brute survival and appetitive drives – that which is “good” extends life or brings pleasure.

This is made very obvious is the opening chapters. Covenant’s leprosy works as the personal version of a motivated evil in a fallen nature – the Foul to his Land. He’s also a totally hapless pawn of materialist delusion. So he bobs like a cork without faith, logos – higher purpose of any kind. And when unstoppable evil attacks – he responds with a hollowed out, insect-like mechanical survival routine.

Consider TC’s answer to leprosy – the VSE. As presented by the leprosarium doctor near the beginning of the book

VSE, Mr. Covenant. Visual Surveillance of Extremities. Your health depends upon it. Those dead nerves will never grow back-you'll never know when you've hurt yourself unless you get in the habit of checking. Do it all the time-think about it all the time. The next time you might not be so lucky.

George Dunlop Leslie, 'Willow, Willow. The Fresh Streams Ran by Her and Murmured Her Moans' Othello, 19th century, oil on canvas

The modern beast system is based on the obvious myth that absolutes can be found in the world directly available to our senses or instruments. Because of that we cling to this fallen dreamscape with animal intensity. And in doing so, lose awareness of deeper truths and ultimately our salvation.

Consider the title of Chapter 2 - You Cannot Hope

One way to understand how leprosy works in the story is to look for the differences from real life. The biggest is that for us, it’s curable. Early treatment is important because the nerve and structural damage isn’t restorable. And questions do remain about it. But Mycobacterium leprae is cleared up with targeted antibiotic regimens. It is possible that the therapeutics weren’t invented when the book was written. But that is beside the point. Leprosy in the book resembles the historical disease, but isn’t the same. Instead it has a Biblical ring.

One way to understand how leprosy works in the story is to look for the differences from real life. The biggest is that for us, it’s curable. Early treatment is important because the nerve and structural damage isn’t restorable. And questions do remain about it. But Mycobacterium leprae is cleared up with targeted antibiotic regimens. It is possible that the therapeutics weren’t invented when the book was written. But that is beside the point. Leprosy in the book resembles the historical disease, but isn’t the same. Instead it has a Biblical ring.

James Tissot, The Healing of Ten Lepers, 1886-1896, watercolor on paper, Brooklyn Museum

The reputation of the disease where it was rare comes from scripture. The “leper, outcast, unclean” that Covenant keeps repeating to hammer home that there is a deeper analogy.

Leprosy," he heard night after night, "is perhaps the most inexplicable of all human afflictions. It produces deformity, largely because it negates the body's ability to protect itself by feeling and reacting against pain; it may result in complete disability, extreme deformation of the face and limbs, and blindness; and it is irreversible, since the nerves that die cannot be restored.

...virtually all societies condemn their lepers to isolation and despair-denounced as criminals and degenerates, as traitors and villains-cast out of the human race because science has failed to unlock the mystery of this affection.

Whichever way you go, however, one fact will remain constant: from now until you die, leprosy is the biggest single fact of your existence. It will control how you live in every particular.

This is important because it sets the leprosy up as an extreme form of material-centric life. One that blocks access the the logos necessary to truly weather it's psycho-spiritual storm.

Ivan Aivazovsky, The Survivor, 1892, oil on canvas

Without something greater, the leprosy inevitably strips humanity away. The process of turning your basic nature against itself in a pure satanic inversion. It's literal.

"Most people depend heavily on their sense of touch. In fact, their whole structure of responses to reality is organized around their touch. They may doubt their eyes and ears, but when they touch something they know it's real. "You must fight and change this orientation."

Donaldson does a decent job of stacking adjectives and other intense language to show how much of Covenant's crappy nature is a result of his reaction - not only to the disease - but to the magic realism advice the TikTok dancer gave him.

...the brutal and irremediable law of leprosy; blow by blow, it showed him that an entire devotion to that law was his only defense against suppuration and gnawing rot and blindness. In his fifth and sixth months at the leprosarium, he practiced his VSE and other drills with manic diligence. He stared at the blank antiseptic walls of his cell as if to hypnotize himself with them. In the back of his mind, he counted the hours between doses of his medication. And whenever he slipped, missed a beat of his defensive rhythm, he excoriated himself with curses.

At this point we're sailing a sea of dysfunction, misinformation and magic realism. It's fair to ask why would anyone want to read about it? Who cares about this character and his pathetic life? Impotent, excuse-slinging losers are a dime a dozen, as are their mewling, self-pitying, point-missing failure-excuse cycles.

After The Chronicles spring the trap, they make the deeper connections and most importantly – show the way out

But we have to start at the bottom. This means stubbornly believing what he wants and thinking his secret mastery can make the world conform. The leprosy not only doesn't make him reconsider his personal gamma fallen nature, it amplifies it. As a materialist coward, survival is his primary concern and now he has a real threat to fixate on. But he’s also self-deluded, so his starting conclusions are all wrong. He accepts the disease by doubling down on his own artistic and personal failure. It’s utterly retarded, but has a cold logic from a gamma impostor in the beast system perspective.

For the first time, he understood part of what the doctors had been saying; he needed to crush out his imagination. He could not afford to have an imagination, a faculty which could envision Joan, joy, health. If he tormented himself with unattainable desires, he would cripple his grasp on the law which enabled him to survive. His imagination could kill him, lead or seduce or trick him into suicide: seeing all the things he could not have would make him despair.

The leprosy as an external, seemingly all-powerful force for evil. One that enters the battlefield between his imagination, creativity, and logos on one side and his truncated, self-absorbed dishonest gamma nature on the other and tips the scales.

Like something satanic in a fallen creation…

A fallen world isn’t neutral. "Neutrality" just clears ground for evil to advance. But active evil supercharges this. Like Foul and the Banes in the Land. Or leprosy and Covenant's gamma self-absorption.

Covenant shows us that lack of positive moral direction is by default a negative one. That in a Fallen world, the natural movement is towards dissolution, decay, death. Readers knew this from the allegory and entropy posts but it’s fascinating to see it presented as fictional sub-creation. Only creative generative activity counters this degenerative force. Whether choosing the Good morally or maintaining a house physically. Without active good, evil wins. As Trell observes in Chapter 6 "mending is harder than breaking".

Jan Breughel II, God Creating the Sun, the Moon and the Stars in the Firmament, 17th century, oil on copper, private

Creation is an act

Willful satanic evil and the natural entropic tendency of a Fallen world towards moral degradation both come from lack of Logos. The rejection of and separation from it respectively. The question Lord Foul's Bane poses is this - if materialism is a path to evil, how does one find logos in a material world? More specifically, how does a broken gamma find logos, considering how far from reality they’re starting from?

Reference to gammas brings in the SSH - Covenant’s situation is a mixture of gamma cowardice and ingrained misunderstanding. All driven towards omega withdrawal by brutal luck and the collapse of his delusion bubble.

Click for Vox Day's video explaining the gamma type in general. We looked at it in our second Dazed and Confused post.

What makes The Chronicles so insightful is the way that Covenant and his/our world creates sets up contrasts with the Land. This lets the book reflect on parallel implications of logos on the personal and external levels. There’s the obvious contrast between the fully vertically-integrated ontology depicted so intensely of the Land and the flat, empty materialist banality of “the real world” (TRW). But we also see the personalization of that contrast when we compare that Land to Covenant’s grimly soulless, mechanical, insect-like existence.

Let’s break it down.

Start with the real world (TRW), and the Land. In one, intangibles like vertical logos are invisible while in the Land they are visible. You can see how element in The Chronicles are applicable to vertical ontology as we see it. The only thing missing is that the part of the Logos is played by the white gold.

The Land had a Creator who casts down Foul outside of time and sends Covenant into the world to save it. The relationship isn't exactly Christian as much as it is applicable to the real world where abstracts aren't visible.

We even have the same distinction between a temporal material existence and timeless abstractions.

Donaldson uses the device of the Arch of Time to refer to the boundaries of Creation. This draws the distinction between the temporal and timeless that we call material and abstract or ultimate realities. This is necessary for storytelling purposes.

Narratives are inherently temporal. They describe changes in time. How does one tell stories of eternal, unchanging realms? God Is. The end. Except it the eternal never ends. If you want to narrate temporal origin legends for Foul and the Creator before creation, you are presenting them in a way that doesn't exist. There's no passing of time. But the Land externalizes the invisible. So what's an invisible temporal distinction here is presented metaphorically with a physical construct. And you can narrate temporal stories on either side of that.

It just makes God very distant.

"Ah," Mhoram sighed, "we do not know that a Creator lives. Our only lore of such a being comes from the most shadowy reaches of our oldest legends. We know the Despiser. But the Creator we do not know." Chapter 15

"This the elder legends tell us: into the infinity before Time was made came the Creator like a worker into his workshop. And since it is the nature of creating to desire perfection, the Creator devoted all himself to the task. First he built the arch of Time, so that his creation would have a place in which to beard for the keystone of that arch he forged the wild magic, so that Time would be able to resist chaos and endure. Then within the arch he formed the Earth." Chapter 15

We really can't speculate too much on the metaphysics of the Land because Donaldson gives us very little to go on. We have the legends from Mhoram and the other Lords which are as vague as the quotes here. We know Foul is horribly real. And the Creator appears as himself at the end of the trilogy - but not in a way that does more than confirm the basic details of the making and marring of the world are true. Beyond that, we can't say much so we'll keep it general.

On the surface the relationships don't seem Christian. On the other hand, all we have are faint legends and the fact of the Creator's existence.

Now consider the Old Testament world from the perspective of living in it. If you weren't adjacent to the prophets, how clear a picture of God would you have? Contrast that to your familiarity with evil in a fallen world. Then ask...

What would the Devil look like to pre-Christians were he physically

manifest in a fallen world and God just the faintest legend?

The Real World is complex. It includes the real world of Covenant in the books and the real world that we the readers live in. They are meant to be connected but are different. Put that aside for now because the real world here and there also breaks down further into personal and larger-scale factors. Large-scale, the invisibility of metaphysicals is a petrie dish for the lies and banalities that comprise our demoralized Flatland. Personally, it fuels immorality and pathological personality patterns like gamma.

Here's the preliminary graphic.

The biggest thing here is the way that the Land externalizes things that are invisible in the real world here or there. Thinking further, we need a three-part schema - the real world as we know it, the Land, and Covenant. TRW in The Chronicles is so mediated through his unreliable perceptions that the division is really aspects that correspond accurately to our world and his distortions. Rather then juggle all these permutations, we can think our reality, the Land, and him. What we will see is that intangibles externalized in the Land are internalized by Covenant on the personal level.

Once you see these intangible - externalized - personalized relations, things deepen and clarify in a hurry. Start with the nature of good and evil - satanic inversion and a fallen world. Consider:

Foul is physically present in a way Satan isn’t,

while having all his supernatural qualities

of both originator and archetype of evil.

It’s interesting how Donaldson externalizes this. Take the fallen world as we experience it. We are revealed its nature scriptually, observe its effects empirically, and understand things through it logically. But we aren't explained the mechanics - why and how promordial rebellions transformed the nature of Creation.

Alexandre Cabanel, The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Paradise (Paradise Lost), around 1867, oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Something is clearly wrong, but the inner metaphysical mechanics of the Fall aren’t spelled out in our world. Satan rebels, Adam and Eve follow, and the existential nature of reality changed.

Something is clearly wrong, but the inner metaphysical mechanics of the Fall aren’t spelled out in our world. Satan rebels, Adam and Eve follow, and the existential nature of reality changed.

Death comes into the world, which is another way of thinking about transitioning from timeless to temporal. But how and why the rebellion and introduction of evil has the specific effects it does aren’t explained to us and are beyond our direct perception. We observe the effects and how they fit logically but the divine motivations are above our pay scale.

We know Creation is a process of pure goodness, love, and beauty in both worlds. What we refer to as the inherent glory of Creation or the beauty of material logos. Start with Mhoram's account of the legend and compare it to Genesis and the Song of Songs. Mhoram describes a gamma self-conscious version of a creator God in Chapter 15.

Now for Genesis. We've omitted the repetition of "and it was good" for the main point. That when God creates, there is no expressed concern over the feelings of the created. Or if there are, they are not even hinted at in the text. At the level of ultimate reality, the Good simply is. Looking to impress the crowd is more Donaldson than King David.

God's will is above judgment and synonymous with Good, Truth, and Beauty. As this decends into an ontological hierarchy, lower manifestations of these qualities are echoes and fingerprints of the transcendent glory of God in creation.

The pleasure is reciprocal - Creation praises God for the gift of Creation and the beauty that that entails. Consider Psalm 148:3-5

The Land externalizes this in different ways. The supersensory appearance - like synesthetic beauty - is the most obvious. Then there’s the Earthpower – a sort of white magic that the servants of the land use to battle dark powers and perform supernatural feats. It is also behind the various miraculous treasures of the Land – healing loam, treasure-berries, and so forth.And the inherent goodness - praise for the creator in the beauty of the creation - explains Foul's attacks on the integrity of natural phenomena. Like perverting the light of the moon - to Drool's red in Lord Foul's Bane and the green of The Power that Preserves. Whar better way to externalize the inherent drive in evil to pervert and invert the good. It can't create. It can't even coexist.

It's a sunset, but it gives a sense of the deep wrongness of a bloody moon.

Attack God by attacking his creations. So sick of a-holes that can't see this.

Applicability: Evil opposes Creation/Good/God definitionally. Consider how many ways this plays out in the real world around you. Think how helpful realizing the aggression of evil is for recognizing danger.

Both levels of evil are externalized in the Land. The passive evil of the fallen world comes when Foul mars the primordial goodness of Creation by implanting banes - items of terrible magical power - in it. One such violation is credited with the upheaval that split the Land with a massive cliff called Landsdrop. Here's Mhoram again - "unfounded legends, caused by sacrilege which buried immense banes under Mount Thunder's roots. But it stands across all the Land, and does not allow us to forget."

Foul is then cast into the world by the enraged Creator, where he is trapped within time. Thus he really is the Prince of this World – an abstract being of vast power imprisoned in material temporality where her hurls his hate, fury, and sheer malevolence at the destruction of the Creation.

"Alas, he did not understand Despite, or had forgotten it. He undertook his task thinking that perfect labor was all that he required to create perfection. But when he was done, and his pride had tasted its first satisfaction, he looked closely at the Earth, thinking to gratify himself with the sight-and he was dismayed. For, behold! Buried deep in the Earth through no will or forming of his were banes of destruction, powers virile enough to rip his masterwork into dust.“Then he understood or remembered. Perhaps he found Despite itself beside him, misguiding his hand. Or perhaps he saw the harm in himself. It does not matter. He became outraged with grief and torn pride. In his fury he wrestled with Despite, either within him or without, and in his fury he. cast the Despiser down, out of the infinity of the cosmos onto the Earth.

Beauty, life, creation, and the good are all linked in the Land’s radiant energy and vitality – color metaphorically and literally.

On the other hand, Foul is called the Gray Slayer.

Foul is also external to the material world. This is something of fundamental importance that he and Satan share. It's the key to their seeming invincibility. We do not know if he was created earlier like Satan or co-eternal. But we know he isn’t the Creator, so he isn’t applicable to ultimate reality in a logos sense. He corresponds to the eternal abstract level of reality who is is also an agent in this world – again like Satan. When we understand what the Prince of the World is ontologically, it is clear why he is unbeatable long-term in worldly terms.

If Foul / the Devil is external to the world, then he is not

ontologically opposite a created thing in the world.

This is just logic. His opposition is to the Creator – they aren’t ontological equals, but from our perspective, they are immaterial forces waging a conflict in our world that we can’t engage directly. It’s way beyond us.