If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Occult posts like this one - posts on the history and meaning of occult images - have their own menu page above. All posts are in the archive on the right.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry.

It's been a while since an occult post - just too much to think about and not enough time to write it all. The last few regular posts have been art heavy, and the two big ones on Gothic architecture got us thinking about the meaning of "Gothic" outside of medieval art.

As one blogger put it: "The genre of Gothic literature is usually defined as some combination of horror and romance, physical spaces play a big part (think spooky houses and lonely cemeteries), misunderstandings, mistreated women, quest for the sublime (huh? I’m going to have to research that a bit), doubles, madness, and hereditary curses. How absolutely fabulous."

Not being morally inverted we take issue with the final sentence, but this is otherwise a fine summary.

To be technical, the Gothic refers to a genre of medieval art and architecture that started in France in the 12th century, spread quickly across Europe, and dominated until the Renaissance. It's defined by pointed arches, stained glass, graceful linear beauty, and general devotion to God. Of all the forms of Western art, it may be the purest expression of Logos - that connection between man and God that expresses itself in the order of nature, morality, and faith. If you're interested, here are two big posts on Gothic architecture - click for part 1 and part 2.

Like the stained glass light coming through the 13th century Rayonnant Gothic windows in the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis in Paris.

But somehow it got inverted into the exact opposite on the eve of the modern era.

Somehow...

Since occult posts deal with satanic inversions and supernatural-flavored evil in more of a popular sense, this seemed a good opportunity to look into how this visual praise of the Holy - the Good, the True, and the Beautiful - became twisted into darkness, horror, and the diabolical. Abbot Suger, the French cleric who invented the Gothic hoped that with his beautiful style "man may rise to the contemplation of the divine through the senses". We'll venture out onto a limb and suggest that is probably wasn't a coincidence that this that got drenched in filth and perversion in a morally inverted age.

Title page and frontispiece to Matthew Lewis' The Monk, from around 1818. The book was first published in 1796 and is considered a pioneer of the Gothic genre.

Of course it's in a monastery.

The first problem is the word Gothic. People in the Middle Ages didn't use it. When the Gothic style spread to England it got called the "French style" at first, then picked up its own English names as it evolved. The term was coined by Giorgio Vasari, a 16th-century sycophantic a-hole who was trying to disparage medieval art for his preferred Renaissance classicism.

Filippo Brunelleschi's design for San Lorenzo in Florence is early Renaissance classicism. The proportions are perfectly harmonious, but there is none of the wonder or splendor of a Gothic interior. The vaulting is simple, and the nave a primitive shoebox.

The simplistic, repetitive, building block structure is supposed to be "rational" but it's just a soulless forerunner of modern globalist monotony. The appeal is in the well-carved mouldings.

Vasari's Gothic referred to the Germanic tribes that migrated into Europe at the end of antiquity and destroyed the Western Roman Empire. At least that's how Vasari put it - savage Gothic hordes extinguishing the lamp of ancient culture. But Vasari was a sycophantic a-hole and anyone with a smidgen of familiarity with ancient history knows that late antique Rome was a cesspool of corruption with an ungovernable mob that was already circling the bowl. The capital had been relocated to Constantinople for almost a century and the Western capital had recently moved to Ravenna. One might say that the extirpation was a mercy killing.

Trainwreck rulers like the inept boy emperor Honorius didn't help.

John William Waterhouse, The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius, 1883, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of South Australia

Pigeon boy notwithstanding, Vasari's fable was influential - influential that the myth of the collapse into the "Dark Ages" rather than gradual decline still lingers among the ignorant and dishonest.

Like Boomers still believing that the lies told to them by corrupt globalist media have any relation to reality. Truth doesn't matter in practical terms if you act as if lies are true. That's how glamour works [click for a post on the glamour of fake media world]. The Renaissance myth of a "dark age" was the same sort of glamour - a lie that may as well have been true because the thoughtless masses took it as such.

So "Gothic" came out of the Middle Ages with two historically weak meanings:

soaring light-filled cathedrals like Cologne that weren't built by Gothic tribesmen...

...AND...

...a caricature of the dark ignorance of tribal savages who didn't build "Gothic" architecture.

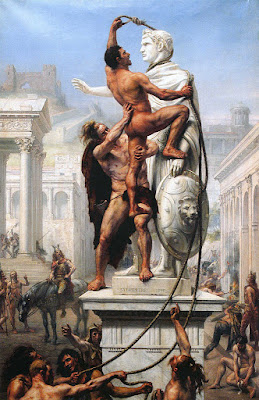

Joseph-Noël Sylvestre, The Sack of Rome by the Barbarians in 410, 1890, Musée Paul Valéry, Languedoc-Roussillon

So what does any of this have to do with "Gothic" literature?

The short answer is not much. The longer one is it's complicated. But the starting point is that the adjective "Gothic" that was connected to lurid tales of fear and depravity meant contemporary impressions of the Middle Ages, not anything historically accurate or meaningful. The stories sometimes had medieval settings, though often not - a graveyard or English manor house could be as spooky as an old castle. And when they did, Gothic art and architecture was irrelevant to the plot. It's actually fair to say that the Gothic in Gothic literature refers to a vague sensation - the stories created a feeling that resembled the feeling that 19th century historical ignoramuses got from visiting a Gothic ruin at night.

Like Tintern Abbey

Tintern Abbey had mix of styles built from 1131 to 1536. Most of the abbey church was built in the Decorated Gothic style 13th century and consecrated in 1301.

Life at the abbey ended in 1536 when blasphemous pig Henry VIII declared himself head of the English Church - ?!?! - and Dissolved the Monasteries.

The obese murderer stole the valuables and sold the land to a sycophant, Henry Somerset, the Earl of Worcester, who sold the lead from the roof and let the building fall into decay.

Ladies and gentlemen - spiritual leadership!

Gothic literature is considered part of the Romantic movement that reacted to the logic and Classical style of the Enlightenment. The basic idea is that the obvious limitations in the strict rules of the Age of Reason stifled creativity, so creators turned to the opposite - emotion and irrationality - for inspiration. Tales of terror, supernaturalism, and perversion were pop culture versions of that Romantic impulse.

Renewed interest in the medieval past was another part of that Romantic culture, although not the sort of interest that we would associate with a responsible historian. The Romantics loved medieval ruins, especially at night for several reasons, all tied to what was a solipsistic cult of feelings.

Peter van Lerberghe, A Visit to Tintern Abbey by Moonlight, 1812, watercolor, British Library, London

The architecture was Gothic and not the Classicism associated with Enlightenment "reason". Ruins were evidence of the passing of time and the assurance of death, not the timeless classical ideal associated with Enlightenment "reason". The broken uneven forms provided a mysterious atmosphere, especially at night, and not the classical clarity associated with Enlightenment "reason".

Van Lerberghe does a good job of capturing the way the Romantic fascination with ruins became an exciting "emotional" experience. The moonlight and torches add to the uncertain atmosphere being enjoyed by groups of thrill seeking tourists. Its a deliberate attempt to create a mysterious and spooky atmosphere.

The "Gothic" in Gothic fiction is this feeling turned into a narrative where the supernatural and danger can really happen.

H. A. Hennings, Tintern Abbey, around 1840, engraving published by John Tallis, for Curiosities of Great Britain, National Library of Wales

Calling it a tourist attraction is fair - here's a mid-19th-century guide showing visitors to Tintern Abbey having the same kind of spooky nighttime experience.

Studies of Gothic fiction take different angles. But whatever the approach, all take it a reaction to social and/or psychological changes of Modernism. The subconscious underside of freedom, consumerism, materialism, feminism - whatever shoebox ideology the interpreter wants to put culture and history into. Romantic medievalism fits this because it represents a sort of nostalgic look back at less complicated time.

But medieval architecture had another important characteristic that doesn't get attention - it was overtly religious in a way that early modernity wasn't. Not religious in a real, spiritually meaningful way - that would have required historical responsibility and philosophical honesty. But "religion" in quotation marks - the Enlightenment view of it as a remnant of superstition that Enlightened England had evolved past. From this perspective, the rituals and mysteries of the church were more or less interchangeable with ghost stories, fairy kingdoms, witches, and other elements of folklore. Things that go bump in the night.

1880s Ghost Story Victorian Trade card

There's actually nothing "medieval" in this Gothic setting.

Consider the founder of Gothic fiction. Horace Walpole (1717-1797) was the son of powerful English Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole and a "writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian and Whig politician" according to Infogalactic. Described as pale and effeminate, sexually repressed and a Freemason, he actually wasn't exceptionally sinister - relative to the debauched aristocratic creeps that he rubbed shoulders with.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Horace Walpole, 1756-1757, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery London

Putting aside the naive gushing about wags and wits, Walpole seems a bit of a wad, but far less objectionable that pals like George Selwyn.

A lot of people don't realize how immoral and dyscivic the early modern aristocracy was. Sexual perversion was commonplace with outright wickedness - sadism, pedophilia, necrophilia - not raising too much of an eyebrow. It's a combination of lives of idle wealth and the typical elite pattern of seeking continual thrills in a context where there the idle wealthy were numerous and there was little moral counter pressure.

What happened is that aristocratic immorality trickled down to the mainstream and cretins like Selwyn became represented as somehow admirable. Gothic fiction was one of the early ways that this elite taste for the immoral transferred. But this doesn't answer why the term Gothic was used for Walpole's new genre of story.

What might help is to consider his interest own early interest in a generic notion of the Middle Ages - early relative to the Enlightenment Neoclassicism that was the dominant style in mid-18th century England. Walpole is actually pretty famous in the history of architecture for helping the Gothic revival style to become fashionable in England.

Walpole's Strawberry Hill was a house in Twickingham that he rebuilt in stages from 1749 to 1776, adding medieval themed features. His prominence made it sort of a social icebreaker that opened the way for the full-blown Gothic Revival of the 19th century.

If Strawberry Hill doesn't look all that Gothic, it's because there were two phases to the Gothic Revival. Most people think of the 19th century expression of British culture and identity behind things like the parliament buildings and William Morris prints. The thing is that the emotionalism of Romanticism had different aspects - this later, better known phase of Gothic Revival is connected to nationalism, tradition, and authentic craft tradition.

Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin, Palace of Westminster, 1840–76, London

The Perpendicular Gothic of Parliament was a uniquely English style and intended to distinguish English government from the generic Enlightenment classicism of other capitals - think Washington DC. It was a nationalistic statement of continuity with English history and identity.

George Jack, Inlaid Mahogany Sideboard, around 1887, designed for Morris And Co.

William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement was inspired by medieval designs but more focused on reviving medieval craft traditions. Hand made quality and attractive aesthetics as a counter to the shoddy monotony of Industrial Revolution mass production.

Walpole's Gothic Revival - like the Gothic of Gothic literature - comes from the earlier, more individualistic phase of Romanticism -the aesthetics of personal feeling over reason and emotion over logic. The famous backlash against all-controlling Enlightenment rationalism. It's important to remember that this is an aesthetic attitude - all art is emotional or rhetorical. And how art is interpreted depends on the context - what people take things to mean. So "logic" and "emotion" aren't some kind of pure abstract absolutes - they were were based on assumptions and expectations at the time for different kinds of signs and symbols.

It's an easy contrast to see in painting:

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

This Neoclassical painting is obviously highly rhetorical - theatrical gestures, dramatic lighting, intense subject. It's "logical" in a classical sense for its clarity and harmony - symmetrical, with clearly defined figures acting out a moral. In this case, unity in defense of the nation regardless of cost. The moral is rationally presented, while the rhetoric heightens the feel of gravity and importance.

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, 1820, oil on canvas, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden

The Romantic painting is all about mood and atmosphere. The setting is unclear, the figures not sharply defined, and the story is not familiar. There is no clear moral message. If the classical painting shows us an intellectualized Platonic ideal vision of the world, the romantic painting shows us the mystery and the deep feelings that that mystery can create.

This shows what we mean when we observe that Romantic emotion and Classical logic aren't absolutes as much as attitudes. Both paintings are rhetorical in that they play on emotions. Both are rational in that they depict coherent scenes. But one uses conventions that were associated with logical clarity and objective moral messaging and the other mood, mystery, and inward subjectivity.

In architecture, classical clarity was conveyed by, well, classicism.

Colen Campbell, Stourhead House, 1720-25, Wiltshire, England

The simplicity and clarity of classical architecture was an equivalent to the clarity and harmony of classicism in painting. This is a bit early for the Enlightenment - England was onto classicism and reasonableness early - but it was the same connection between the classical and reason that made Neoclassicism the Enlightenment style.

Here, forms derived from the ancient architecture of classical antiquity suggested the timeless ideals of reason and virtue. That's why classical architecture appeared all over - making it the architecture of proto-globalism, just as Enlightenment rationalism and equalism were fake ideologies of proto-globalism.

So Strawberry Hill didn't have to be historically accurate to represent an "emotional" alternative to classical reason. It just had to represent an opposite. Something expressive of personal feeling and local custom rather than universal rationalism.

Since the classical had been the standard since Vasari and the Renaissance, the "Gothic" was revived as the counterpart. It isn't something inherent in the style so much as the whole early modern attitude towards art being built on a fake dichotomy between "Classical" and "Gothic". Or what a postmodernist would call the "discourse" of art, and not be wrong in this case.

The Romantic Gothic ruin was a combination of medieval architecture as the antithesis of Classical reason and the the mysterious mood created by the ruins as the antithesis to logical clarity.

Sebastian Pether, Moonlit Lake with a Ruined Gothic Church, a Church and Boatmen, 19th century, Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire

Like this textbook example of an emotional, atmospheric scene with a medieval ruin.

The Gothic picks up a collection of irrational, emotional, subjective Romantic associations because of its appearance and the significance of that appearance in its context. Strawberry Hill is so important historically, because this is where the process of accumulating these associations started. Walpole gradually transformed it into a sort of medieval theme house, with decorations inspired by his take on the English Middle Ages. Not in a serious historical or archaeological way but as an aesthetic.

The Rooms are more medieval flavored than authentic medieval recreations. The library is an attractive space but obviously cosmetic.

The features on the exterior were wood and plaster props and each room was put together by his aristocratic friends.

Architecturally the "Gothic" stylings were an alternative to the prevailing classicism in vogue at the time. And these stylings creates an emotional impression that was a perfect fit for the Romantic concepts of emotionalism and subjectivity that were just around the corner in time.

There are two important things that Walpole represented

1. the idea of the Middle Ages as a style or attitude rather than a historical reality to be known through historical study. An alternative to the Neoclassicism of the Enlightenment.

2. the Middle Ages as a feeling. An alternative to the the "normalcy" of modern life. Walpole coined the term gloomth - something both gloomy and warm.

It's more accurate to call Walpole's Gothic house generically medieval, but the Gothic in Gothic literature is also at best generically medieval. That is, when it isn't evoking the Middle Ages at all - just the spooky ambiance that Romantics associated with old ruins.

Sebastian Pether, Landscape by Moonlight, between 1825 and 1849, oil on canvas, Shipley Art Gallery

You can get the same moody Romantic atmosphere with an old windmill.

The combination of gloomy and the generically medieval would appear to be behind the use of Gothic to describe melodramatic supernatural horror. Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764) is generally considered the first Gothic novel. The story framed as a recovered manuscript from the 16th century based on an even older medieval account found in the library of "an ancient Catholic family in the north of England". Walpole dropped this pretense with the second edition and admitted his authorship. He described the book as a combination of what he called ancient and modern romance. According to him, ancient romance was fantastical but unbelievable and modern romance naturalistic. His formula - which would become the basis of Gothic until the present day - was to mix realistic people and actions with fantastic and or supernatural elements.

Title page of the third edition. From the second edition on, the subtitle "A Gothic Story" was included.

What isn't clear is where this came from. The available sources all claim Walpole was the first writer of Gothic fiction. We know that the term Gothic was used for medieval art and culture since the Middle Ages, and in Walpole's time the Middle Ages referred to a style or attitude that evoked certain feelings.

It appears that the literary "Gothic" was introduced by Walpole or his publisher to connect the spooky melodrama and supernaturalism of his story to that feeling.

But merging the natural and the supernatural doesn't capture the specifics of Walpole's invention. That could take many forms. His Gothic is the merger of terror and a stereotyped medievalism. Consider this engraving of the actual castle at Otranto that Walpole likely saw on his Grand Tour of Italy. It's obviously medieval but has nothing Gothic about it in the architectural or historical sense at all:

The Castle of Otranto, from the works of Horatio Walpole, Earl of Orford. In five volumes, London : G. G.and J. Robinson and J. Edwards, 1798.

Generically medieval.

The plot of The Castle of Otranto told of a lord Manfred whose son was crushed to death on his wedding day by a giant falling helmet, triggering prophecies and leading Manfred to force his son's young fiance to marry him. The events that follow include things that will become trademarks of the genre - secret passages and meeting places, moving pictures and doors, prophecies, and other supernaturalisms. The tyrannical cruel lord of the castle is an element of what will become the most famous of Gothic creatures - Dracula. Perverse and misdirected sexual lust is another staple.

An engraving depicting the gigantic helmet from The Castle of Otranto: a Gothic Story, London: J. Limberd, 1824.

There really is a giant falling helmet.

Of the Gothic authors that spring up in Walpole's wake, Ann Radcliffe is probably the most talented. Her stories tend to tease supernatural elements only to reveal them as natural occurrences. Matthew Lewis' The Monk goes in the opposite direction - a lurid story of murder, rape, incest, ghosts, sorcery, and demons that ends with the protagonist selling his soul to Lucifer and dying horribly. Even before the turn of the 19th century, the Gothic is becoming hard to define as a formula and growing more detached from medieval influences.

In more philosophical terms, the Gothic gets connected to something called the Sublime, a Romantic idea that replaced the appreciation of classical beauty and ethics.

Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss, 1787-1793, marble, 155 ×168 cm, Louvre

Classical beauty was rationally based - derived from the Platonic connection with Truth and the Good through logos. It was an intellectualized ideal that brought harmony, symmetry, proportion, grace, clarity, etc. to an imperfect world. Note how flawless and perfectly balanced Canova's sculpture is. It is classically beautiful.

The connection between the beautiful, the true, and the good added a moral dimension as well. This was the argument for correct rules and values in classical art.

The sublime was the opposite. An overwhelming - and therefore irrational, as in beyond the mind to rationally comprehend - brought on by something that vastly surpasses us. It was an ancient idea as well, first appearing in Longinus' On the Sublime, probably in the 1st century AD, though date and author are uncertain. His argument was that human emotions can transcend the limits of the human condition because our imagination can carry us past empirical experience. Poetry does this by using metaphor to hint at things beyond description that the imagination transforms into feeling.

Painters turned to wild depictions of the overwhelming power of nature, like the helplessness of Hannibal's mighty army before a mountain storm:

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps, 1812, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London

Longinus' process sounds almost mystical - full of transports, uplifts, and souls in flight as he himself tries to produce a feeling that can't be described directly. The best word might be awful, in the old sense of awe-full. And it is sort of mystical, because many Romantics were trying to capture larger than life feelings that were essentially religious, only in secular material subjects.

Caspar David Friedrich, The Cross beside the Baltic, 1815, oil on canvas, Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin

Some Romantic artists looked for the sublime in Christian themes like Friedrich, one of the first Romantic painters.This was unusual as most were looking to replace religion as a source of awe and other strong feelings.

The sublime got a new life in time for Romanticism in Edmund Burke's A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful of 1757, just before The Castle of Otranto. Burke also saw the sublime as an awe-fullness beyond reason, but explicitly connected this to terror. In the arts, the sublime is simply the strongest possible emotion that can be created, and since Burke believed self-preservation is the strongest impulse, threats to it - pain and terror - bring out the strongest passions. Burke's formulation became the basis for the Romantic sublime and for Gothic literature. It's worth quoting because it's revealing:

WHATEVER is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling...

But as pain is stronger in its operation than pleasure, so death is in general a much more affecting idea than pain; because there are very few pains, however exquisite, which are not preferred to death: nay, what generally makes pain itself, if I may say so, more painful, is, that it is considered as an emissary of this king of terrors. When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are, delightful, as we every day experience.It's easy to spot the cheap solipsisim behind Burke's words. This spiritually-constipated pissant was too fixated on his feeble materialist "values" to look out at the true sublime depths of reality. He links pleasurable feelings to "society" and opposes that to self-preservation - a false dichotomy between the animal fear of death and physical comforts in the herd. His stunted awareness is incapable of moving past protoplasm twitching to material stimuli.

A faithful Christian - a true man of the West - has no fear of death.

George Inness, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1866, oil on canvas, Francis Lehman Loeb Art Gallery, Poughkeepsie, New York

Pain may be best avoided, but death is only the "king of terrors" to self-centered materialists.

,

On this level, Enlightenment "rationalism" and Romantic "emotionalism" are two facets of a solipsistic Flatland, where myopic narcisists believe things come from nothing and that limited human minds in a temporal world can grasp absolute transcendent truths. In other words, the vain and nonsensical "intellectual" culture that ultimately gave us modernism.

Frontispiece to A Visit to the Celestial City - Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Celestial Railroad (1843), revised by the Committee of Publication of the American Sunday-School Union, Philadelphia, American Sunday-School Union 1844

Click for a link to a scan of this text, and for a link to Hawthorne's original story.

It's that tiresome idea taught by globalist historians that the de-moralized materialist Flatland that we live in is natural and inevitable. It's the same Progress! of vanity we've seen again and again - the abject idiocy that improvements in engineering can answer metaphysical questions. That because we can make a cellular call or grind a lens we can pass existential judgments about the meaning of reality and our place in it.

Hawthorne absolutely nails it in his allegorical sequel/parody to Bunyan's A Pilgrim's Progress. It's a short story. We highly recommend reading one of the provided links.

It sounds utterly retarded when stated this way but just look back over the last few centuries - that's exactly what's happened.

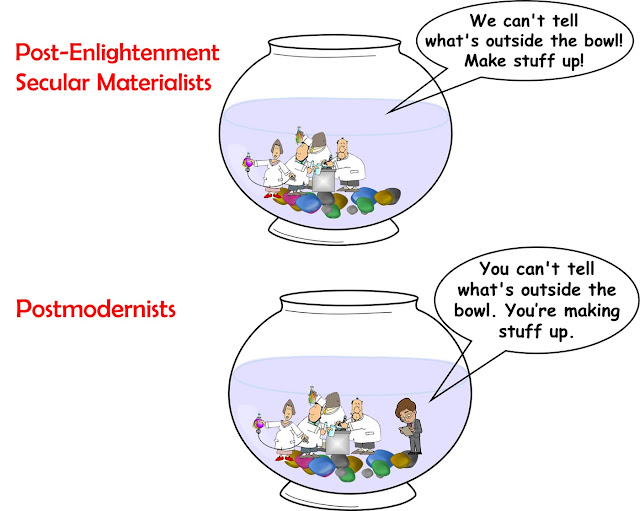

Of course, these are the same smug clowns who were aghast when Postmodernism took their inverted faith to it's logical extreme and laid bare the logical contradictions at its rotten heart. No, idiot materialists, you can't attain Truth with empirical observations in a temporal world from a subjective perspective. It's inherently impossible, a category error of the highest order. And any belief that your subjective impressions rise to that level can be deconstructed effortlessly. Why? Because they're subjective impressions! Let's dumb it down so the secular materialists can understand.

Picture a fishbowl:

What we can offer is the actual scientific method - observation, replication, abstracted conclusion, which is logically sound but builds outward. Measuring and describing our material reality can't reach the preconceptions of that material reality. It can't reveal ultimate origins, ultimate meaning, or ultimate reality. It can't reach Truth with a capital T, and because of this, absolute morality escapes it as well. But is is factual for what it is.

And what can the materialists offer?

Mimzi Haut, Resting Place, 2020, acrylic on gesso and wood

The triumph of Reason? They're all dead.

Endless growth? The world is finite. It ends at some point too. It's called math.

Clinging to years of life expectancy? They still all wind up dead.

It turned out to be a bit short of "timeless"... And even a materialist should be able to see the problem:

Burke's sublime wants to escape the limits of Enlightenment reason without admitting that the conclusions of that limited reason also have to go or be supported with new arguments.

"Reason" can't provide the keys to reality, but it's false prophets lied and claimed it did. And in making their fake claim, they tore down the Western Logos that anchored human existence to legitimate higher principles. Or at the very least hid it - its not that the Logos cares about the blatherings of liars, but the system of materialist greed and vanity transformed the culture. But when Enlightenment Reason! flopped, Western "leadership" didn't return to something sound - they just got more vain and moronic. The materialist conclusions of the Enlightenment taken as True! even after realizing that the "reasoning" for those conclusions was bogus. It's so masturbatory and stupid that its a bit embarrassing to be of the modern West.

Just look. It's literally this dumb:

Enlightenment: Fake reason says there is no metaphysics!

Fake reason proves fake

Romanticism: There's no reason, but we still know there's no metaphysics because...

because...

because...

because...

We're collectively retarded is first answer that springs to mind, but vanity and hedonism is closer to the truth. If you've dismissed God, and then dismissed reason, you get to wallow in unbridled emotionalism. And looking at the moral and cultural shitstain that is the Gothic provides the proof.

Romanticism is not necessarily immoral, but it has no coherent path to be moral either. This is because it is built on Enlightenment de-moralization - that transcendent principles are somehow present to limited subjective minds in a temporal world. Morality is timeless - higher principles that can't be known materially, only through faith in something. Without that, the will to power is more empirically sound code to follow.

Thomas Cole, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, 1828, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The only question for faith is whether yours is compatible with the empirical world or not. The Christian notions of the Fall and the reality of evil are a far more objective fit with the world of our experience than inane blather about the benevolence of mankind or complete human interchangeability.

Ask yourself if the "morals" you profess are logically and empirically sound. Look carefully. If they aren't, ask why you cling to them and what you have faith in.

What does this have to do with the Gothic? It's actually simple. The Gothic wasn't the irrational reaction to an inevitable, rational modernity. Because that "rational modernity" was already the satanic inversion of an intellectually-defensible notion of reality where faith, logic, and observation worked in their proper domains. It is a consequence, an outcome of the grotesque Enlightenment lie. Without metaphysics "beauty" - classical or otherwise - is just emotional response. By rejecting God and reason, Romanticism wallows in the subjective, treating dopamine hits as the highest artistic value. Romantic works can stunning, even breathtaking because the Romantics get very good at generating dopamine. Sometimes legitimate beauty shines through inadvertently. But the ideology itself is just cheap thrills - there's nothing of substance there.

"Gothic" morality is built on the pretense that Christian notions of "good" and "evil" exist without Christian reasoning behind them. Lewis is unusual for including overtly Christian notions of salvation and damnation because Gothic supernaturalism tends to treat religion like magic when it includes it at all. Neither Walpole nor Radcliffe align virtue with religion, and the vampires and the like of the 19th century are not Biblical villains. Although for some reason crosses and holy water hurt them. Along with random things from folklore. Christianity is just more folk magic to be enjoyed in a fantastical story of things going bump in the night.

And bizarre misrepresentations of Catholicism as a source of supernatural mystery go hand in hand with the "medieval" setting. But it's never a Catholicism that demonstrates Christian theology or even virtue - it's invariably an excuse for weird priestly ritual and sorcery in old settings. Even The Castle of Otranto features a "friar" who turns out to be the father of the actual protagonist.

cliford417, Cemetery Gates

It's a good painting technically, but shows the consistency of Christian tradition as a source of supernatural fear.

The notion of holy ground as a lair of evil is indicative of modern satanic inversion, where the holy is denigrated and the perverse uplifted.

Some general themes in this "Gothic" dreck. A big one is the link between evil and excessive or perverse drives. All the Gothic villains have transgressive desires that lead to ruin - generally related to sexual perversion. The thing that they have in common is a lack of check or regulation. Prioritizing desire over all else can also unleash the addict's pattern like we see in The Monk, where the evil acts become more and more extreme. Chasing the dragon all the way to Hell.

According to globalist nonsense history, separating religion and morality is a sign of modern cultural maturity. The excessive desire can be interpreted coming to grips with "secular morality". If that weren't intrinsically self-contradictory. But the real lesson is where appetites and desires can go without something objective and real to check them.

J. Kirk Richards, I Stand at the Door and Knock

That is, real morality, beyond the fake rationalism of the Enlightenment and solipsistic emotionalism of Romanticism alike.

So why "Gothic" literature? How does its de-moralized Romantic sublime relate to the kind of Gothic Revival Walpole pushed? More precisely, why did religious architecture became associated with the most irreligious feelings? Part of it may have to do with trying to capture a sort of secular awe, but Gothic literature is based on things that fundamentally contradict Christian values. It's inversion, but one with a pattern.

Remember, the evocative ruins associated with Romantic sublime "Gothic" terror came from cheap human vanity. When blasphemous greaseball Henry VIII declared himself head of the Church in England, seized all the Church property, and sold many of the great monastic foundations to his sycophants.

Like Fountains Abbey, founded in 1132 and the church built from 1143. It was sold to Sir Richard Gresham in 1540, a good friend of Wolsey and close enough to the king to be present at the execution of Anne Boleyn. Gresham stripped and sold off materials - the estate lands were the real draw. Subsequent owners used stone from the abbey to build the estate hall.

The Band recognizes Catholicism as a legitimate Christian faith - one that's been a historical pillar of the West. Likewise those Protestant alternatives built on Scripture. But there is no possible grounds for Christian legitimacy in a king and murderer declaring himself Christian authority. Theologically, the "Church of England" was an abomination that usurped the spiritual for worldly gain. The medieval ruins that dotted England were foundations that weren't taken up by aristocratic parasites and left to decompose in the countryside. Symbols of faith crushed into mute monuments to the triumph of Mammon.

Likewise the literary "heroes" that expand the Gothic in the 19th century are a morally-bankrupt band of perverse, hedonistic, creeps like Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Joseph Severn, Posthumous Portrait of Shelley Writing Prometheus Unbound, 1845, oil on canvas. Keats-Shelley Memorial House, Rome

Shelley bgave us Prometheus Unbound seen in an earlier occult post - infantile post-Enlightenment luciferian drivel where finite temporal humanity surpasses divine transcendence. And The Cenci (1819) - a wallow in depravity that dramatizes a tale of rape, incest, and murder.

Shelley Memorial, 1892, University College, Oxford

His own moral conduct was atrocious, as expected from his "progressive" political associations - serious question: when is "progressivism" not a euphemism for moral bankruptcy? His second wife Mary made her own Gothic contribution with Frankenstein.

Memorializing these turds is typical of the moral inversion at the heart of the post-Enlightenment materialist West..

Then again, when freed from productive work by family money accrued through exploitation and bored with ordinary luxuries, what is a poor parasite to do but eroticize evil and predation? It was a party on Lake Diodati in 1811 where Byron, Shelley and their parasitic circle pushed the Gothic to new heights. This was when Mary Shelley came up with the idea for her Frankenstein. And Dr. John Polidori, Byron's personal physician came up with a story called The Vampyre that was possibly inspired by an idea of Byron's, was likely a parody of Byron, and was credited to Byron for some time.

John William Polidori, The Vampyre, London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1819 and the "Popular Edtion", London: John Dicks, 1884 with misattribution to Byron

Generally considered the first of the "romantic" vampire stories.

The Vampyre introduces the idea of the darkly appealing vampire with a sexual power attached to their murderous ways. The Lord Ruthven in the story is a prototype for Count Dracula and all the vampire-as-sexy trash that's cluttered up pop culture since. As an archetype, the vampire also represents consumption taken to extreme excess - the logical endpoint of modern de-moralized consumerism. The ceaseless drive to slake appetites leading to contagion, depravity, and death.

Is there a better indictment of our morally inverted societal cesspool then declaring that "sexy"?

Seriously. That isn't a rhetorical question.

Think about it for a moment. Not that evil can have an allure, or snarky dismissals of the low quality of this trash. What is says about a culture when this is openly held up and promoted as appealing.

Was Lord Byron really the model for Lord Ruthven? The link above concludes that it doesn't matter as much as the impact on the vampire legend in general - making it more human, sexy, and "Gothic". Byron was a debauched POS, but the really insidious thing is the use of that adjective here. The notion that the charms of the vampire story - where sexual perversion, rape, murder, violation of the dead give us the ultimate literary snuff porn - is somehow "Gothic". This is absolute inversion - where the ultimate symbol of medieval faith becomes a glorification of the most depraved horror.

This pattern puts the negative portrayal of the medieval settings and the Church in a historical context of progressive de-moralization and self-idolatry. The royal blasphemer and his lords connect straight to the Romantic hedonists and their perversion of the memory of monuments to faith like this one:

Gloucester Cathedral Lady Chapel, Perpendicular Gothic reconstruction begun in 1470.

If you're looking for Vasari's barbarous darkness, that's a fine place to start.

So the "Gothic" in Gothic literature is essentially the sort of setting that morally-inverted Romantics associated with sublime terror, used to jiggle morally-dead victims of modern materialism. And if this means continuing the perverse inversion of medieval architecture of faith all the better, because if there is one thing that peddlers of debasement and wickedness dislike, it's signs of faithful devotion.

St. Thomas Becket Miracle Windows in the Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral, 1182-1220

The reality is this:

If there is something awful in the cathedral, it's because the West failed in its responsibility to protect the True, the Beautiful, and the Good.

No comments:

Post a Comment