It occurred to us that we've been throwing the term Gothic around in the last few posts on the roots of the arts of the West without really defining what it means.

Thomas de Canterbury, fan vaults in the cloister of Gloucester Cathedral, 1351-1377

Beautiful early example of the Perpendicular Style - the last of the three phases of English Gothic. The Gothic style began in France and spread all over Europe, taking on regional variations. Historians divide the English and French into three stages each, but the features are different.

In the last post, we made the claim that the Gothic period is where we can really start to see a split between the logical concept of art based on our Greek terms and the venal interests of a self-deifying elite. We've considered a lot of artworks from the later Middle Ages and looked at the change from a relatively productive feudal concept of noble to a parasite class that lived off the labors of the masses without contributing anything beyond some patronage of culture. But before we move into the basket of nonsense generally called the Renaissance, it makes sense to explain what the Gothic is, how it relates to society, and the connection to what comes later.

Dominique de Florence, Flamboyant Gothic entrance to Albi Cathedral, added 1392

The Flamboyant Style was the final phase of the French Gothic - roughly equivalent to the Perpendicular Style in England.

The point of this post isn't to analyze every permutation of the Gothic, but to lay out the basic principles, important developments, and historical significance.

This is going to be more of an art-focused post, rather than history or philosophy, although you can't really separate them. The idea is to work out what the Gothic was artistically, how it connects to Logos, why it was corruptible, and what it has to do with the Renaissance. Nothing too overly long - there are lots of good books out there if you really want to go deep - but for two reasons:

1. A way to take the pulse of the art of the West as we move onto the runway that will eventually bring us to modern times...

... and that accursed Armory Show of 1913 which is hanging in the distance like a grail.

2. A way to think about the relationship between art and Logos that is completely missing from the inverted Art! discourse of globalist modernity.

This will set us up for the next roots of the West post and a look at the Renaissance. We're also due for a more speculative philosophical post which will springboard from the Heidegger one and consider the relationship between art and ontology. In addition to occult posts and something more positive.

The Gothic actually has a connection to the sort of things we look at in occult posts since it was the victim of a satanic inversion in the early stages of modernism. Gothic art was first developed to praise God with beauty and awe. Now think how the modern usage is associated with dark horror and the occult. Anyone think its a coincidence that the soaring vaults and pointed arched of medieval cathedrals became settings for perversion and evil?

Relatively tame example of "dark Gothic" "art" from an internet search.

Consider the extent of the inversion to make the purest example of the artistic expression of Christian devotion into a symbol of moral decadence and depravity. It's easily taken for granted, but breathtaking in its perversion when you really think about it.

Didn't think so. If they can't destroy it completely, they'll try and cover it with filth so it's unrecognizable then twist it into its opposite. Consider us a pressure washer.

As mentioned in an earlier post, the Gothic style starts in architecture. We looked at Abbot Suger and the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris as a place where the distinction between sacred and secular really collapses artistically. The good abbot was obsessed with gold and gems in decorating his abbey, and the church itself was intimately associated with the French kings by its sprawling necropolis. But there was another side to Suger's philosophy. Put aside his lust for lucre and quarrels with St. Bernard and the austere Cistercians for a moment, and consider his defense of splendid decoration.

Stained glass light falling on the royal tombs in Saint-Denis.

Suger argued that the light through his stained glass windows that glittered of his precious ornaments was an earthly metaphor for the far more beautiful light of heaven. And in his renovated choir, one came as close to experiencing the divine as possible here on earth. One thing the Band is wary of is linear thinking - that there can be one path, one explanation for something. Reality and motivations are complex. Suger was BOTH a materialist tool of royal power AND a believer in the power of beauty to lift the mind towards God. That they are ultimately contradictory is not that important - humans hold contradictory positions all the time.

Stained glass windows in Suger's ambulatory of St. Denis, ambulatory 1140-1144, windows around 1145

So we can see two separate impulses in the aesthetic of Gothic beauty - a reference to the beauty of holiness AND beauty in the service of more worldly things. Looking back, it isn't always possible to untangle them, because the sacred and secular were intertwined in the medieval mind in a way that they aren't in our modern materialist culture.

Religious procession at Saragossa, Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, Paris, between 1332 and 1350, British Library Royal 16 G VI, f. 32v,

It is true that Jesus told us to separate God's from Caesar's, but the reality in the Middle Ages is that Christianity was much more a part of everyday life. Most people viewed themselves as whatever their national identity was AND Christians at the same time.

Life was simultaneously Norman or Scottish or Venetian AND Christian - there were different hierarchies and authorities, but everyday life brought the two identities together.

Not that everyone acted like a zealot, but there really weren't "non-Christian" options to consider. And clergy were classified as one of the main divisions of society. Funding religious foundations and artworks, endowing masses for the dead, and building churches and chapels reflected positively on the donors socially AND represented good works in the the theological sense. That is, charitable deeds that were believed to bring God's favor.

Bishop Edington's Chantry Chapel at Winchester Cathedral, around 1346-1366

The chantry was the English version of a privately funded burial chapel. These were endowed to pay for masses for the dead and were made attractive to draw the prayers of passers-by, both of which were considered helpful to a soul in Purgatory. Win-win, because the church got funds and beautiful decoration. The practice ended when the Reformation axed Purgatory as a concept.

So when we look at the Gothic, we have to be sensitive that it isn't an all-or-nothing thing like the dyscivic trash promoted as modern art and used as a money laundering vector today. It's more subtle - between beauty that serves truth AND allure that glorifies base materialism and stuff.

So what is the Gothic?

As we saw in the Suger post, the choir at Saint-Denis is considered the first example of Gothic architecture, but it is limited in scale. Some of the main features are here, but in a limited way.

And the key to the whole thing was vaulting.

Vaulting just refers to roofing a space in masonry - stone or brick - without needing intermediate supports like columns or piers. The simplest form of vault is an arch.

Arch of Alexander Severus, 228 AD, Roman triumphal arch in Dougga, Tunisia dedicated to Roman Emperor Alexander Severus

This is a semicircular row of stones cut so they are all narrower on the inside than they are on the outside. Once they are all set, each is held by the ones on either side and none fall in. You can see them in this picture of an ancient Roman triumphal arch.

The basic structure of an arch and different configurations. They all work the same way.

To build an arch, a wooden centering was constructed to hold each stone in place until the central keystone could be set. At this point, the structure is self-supporting and the support can be removed. Lower left: centering for a stone arch; lower right: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The original Blackfriars Bridge, London, under construction in 1764, 1764

You can see where the term "vaulting" comes from - the arch seems to vault over the space from one support to the other.

Arches are extremely strong because their load-bearing ability is based on the compressive strength of the stones rather than the tensile strength, which is way more brittle. The only weakness is at the base. The weight of the roof and wall above the arch is transferred onto the supports, but this also creates comparable lateral force and if the base of the arch isn't held in place, it will push outward and the whole thing will collapse.

Supporting the base strongly enough to counter this lateral force is called buttressing. The heavier the load that the arch is supporting, the stronger the buttressing has to be.

The Arch of Alexander Severus above is buttressed by its thick sides.

Pont du Gard, mid-first century AD, Roman aqueduct inVers-Pont-du-Gard, France

A series of arches like a Roman aqueduct buttress each other by each counteracting the outward pressure of the one beside it.

Basic vaulting is very old - going back to Bronze Age Mesopotamia - but it was the Romans who made it a central part of their building. They built with a form of concrete that was faster and more flexible than stone, but the same physics of vaulting applies. Roman vaulting was so common that the basic round arch is often called a "Roman arch". And if you extend an arch over a distance to make a roof you get a barrel vault - the simplest form of vaulted ceiling.

Barrel vaults in the Roman amphitheater at Arles of 90 AD in the south of France. You can see that they are arch-shaped tunnels.

And just like arches, they needed to be buttressed. Along the full length, since they exerted arch-like pressure all the way along.

The vaults at the amphitheater buttress each other like the arches in the aqueduct.

The problem with barrel vaults is that they couldn't be opened up on the sides without compromising their structural integrity. As an extended arch, they needed to be buttressed all along the sides for stability. Only being open at the ends was a problem for builders because it made large windows and doors impossible elsewhere.

You can see this in the barrel vaulted nave of Lisbon Cathedral, built in the second half of the 12th century. It's Romanesque, not Roman, but the same principle applies. There is light coming in from the rose window at the end, but no windows along the side walls. Those have to buttress the vault.

The Roman solution was something called a groin vault - two barrel vaults meeting at right angles and essentially leaning against each other so that all the weight of the roof channeled onto the four corners. This allowed for openings in all four sides like famously seen in the Colosseum.

The groin vault is two intersecting barrel vaults configured so they support each other. All four sides are open.

This did put a lot of pressure on the supports - in this diagram, the massive piers are able to buttress the outward thrust of the vault.

And real Roman groin vaults in the Colosseum built in concrete between 70 and 72 AD. Compare it to the Arles amphitheater up above - it is much bigger and much more open because of the groin rather than barrel vaults.

After the collapse of the Western Empire the secret of concrete was lost. Vaulting was done in stone, and early medieval churches tended to have flat wood beam roofs. It was in the Romanesque period that we saw a few posts ago that vaulted interiors came back - both for fire safety and aesthetic reasons. Barrel vaults came first, and brought the same problems they gave the Romans - stone or concrete, they are terrible for letting in light along the sides. Early Romanesque churches were much darker inside than the older wooden-roofed basilicas with their big windows.

Early medieval churches had aisles running up the sides that were much lower than the main nave, and a timber roof allowed for windows in the walls above the aisles called a clerestory.

Collegiate Church of Saint Gertrude, consecrated 1046, Nivelles, Belgium

The side aisles are groin vaulted, but the larger nave has a wood beam roof. The bright light coming in the clerestory windows can be seen.

The barrel vault and its need for continuous buttressing mostly eliminated the clerestory as a possibility.

Abbey Church of Saint-Savin sur Gartempe, 11th century

The dark barrel vault is clear in this example. Saint-Savin sur Gartempe is unusual for the survival of it's painted ceiling. Most Romanesque churches were colorfully painted, but very little of this remains. You can feel the weight of the massive vault in the picture.

The Lisbon Cathedral above is another good example, though it's unpainted.

The later Romanesque reintroduced the groin vault, which could open on all four sides. This way it could vault the bays of the nave and be open for clerestory windows. But these were still limited in size by an intrinsic limitation in the groin vault as a type. Groin vaults are just intersecting barrel vaults, and as such are massive, heavy structures. The exert tremendous lateral pressure at their bases and require a lot of buttressing. Given the height of the big Romanesque churches, the only available buttress was the mass and thickness of the walls. So even with the groin vault structure, walls had to be heavy and thick to support them and windows kept fairly small for safety.

Abbey of St Mary Magdalene, consecrated 1104, Vézelay, France

Clustered shafts support transverse arches and a groin vaulted nave. You can see the difference in the lighting, with the return of the clerestory windows. The walls are massive and the size of the windows is limited.

The next step in the evolution first appears in Normandy, in the Abbey Church of Saint-Étienne at Caen. This building is considered an important precursor to the Gothic for its use of ribbed vaults to span the nave. These are much lighter than groin vaults and made it possible to start lightening the walls and expanding the windows. It still took some time, but the ribbed vault was a critical part of Gothic architecture.

Saint-Étienne, began in 1066, ribbed vault around 1120, apse replaced by an early Gothic chevet, 1166, towers and spires were added 13th century, Caen, France

Saint-Étienne is still massed and decorated in the Romanesque style, but the six-part rib vaults can be seen criss-crossing the nave and transferring the weight of the roof onto the vertical supports.

Ribbed vaulting technology was fairly old - it appears to have first appeared in the dome of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in the 6th century, but to our knowledge, no one had used it for a nave until Saint-Étienne. In the Gothic it would be adapted into a primary building system. The idea is simple enough - instead of a heavy vault, span the space with a cage of intersecting arches, then use those the support a much lighter and thinner roof.

Hagia Sophia, 532-537, Constantinople

Emperor Justinian's palace chapel was converted into a mosque in 1453 and into a museum in 1935. It carries signs of the city's tumultuous history. The dome is a miracle of engineering - a cage of arches or ribs that carry the weight and allow for an almost unbelievable ring of windows.

The ribs aren't as strong as a full vault - a masonry dome is just an arch rotated 360, like a barrel vault is an arch extended - but it doesn't have to be because it's so much lighter.

And a view of the ribs and windows from underneath,

The structure is clearer from this angle. The ribs support the roofing material, so it doesn't matter if there are openings at the base of the places in-between. Those sections don't bear any of the load.

When adapted to a nave, the advantage is clear. The only thick parts of the rib vault are the ribs, unlike the uniform thickness of the massive groin vault. The rest of the rib vaulted roof is filled with much thinner and lighter masonry webbing that is entirely supported on the ribs.

Which brings us to Suger.

It's fair to say that Gothic architecture was driven by the desire to let in more light. Before you can even consider Suger's argument that his colored stained glass light was a taste of heaven, you need windows big enough to let it in. And Saint-Denis featured two defining characteristics of the Gothic that allowed just that: the rib vault and the pointed arch.

Good look at the rib vaults in Suger's choir ambulatory at Saint-Denis, built between 1140 and 1144. You can see the difference in thickness between the load-bearing ribs and the thinner webbing in between. The pointed shape of the arches is also clear.

The lighter rib vaulted roof exerts less pressure, meaning less lateral force, meaning less need for buttressing. Walls can be less massive.

Diagram from the internet clarifying the relationship between the weight of the vaults, the outward pressure, and the thickness of the walls.

And shifting the load-bearing capacity onto arches instead of the entire vault means that the buttressing is localized rather than spread along the entire vault. Secure the base of the ribs and the space in-between becomes what's called curtain wall - non load-bearing filler walls. The Hagia Sophia could have windows around the base of the dome because the ribs are doing all the heavy lifting. Suger's applies rib vaults to spaces that would traditionally have been groin vaulted, channeling a much lighter weight onto relatively slender supports. This transformed the walls from load-bearing to a system of alternating supports and curtain walls, The areas between the corners of the bays don't have to hold anything up and could become windows.

The structural innovation - ribbed vaulting - enabled the aesthetic innovation - big jewel-like windows letting colored light pour in.

The other Gothic feature appearing at Saint-Denis is the pointed arch. The pointed vault has a clear structural advantage because its shape channels a greater percentage of the load thrust downward, and less of it laterally. Less outward force further reduces the need for buttressing and allows for even lighter and thinner walls.

Diagram showing the difference.

It's the pointed ribbed vaults that let Suger continue to build in stone while reducing the structural supports to thin piers and opening the space in between for glass curtain walls.

As an added benefit, ribbed vaults are more flexible. While groin vaults need to meet at 90 degrees, ribs can be launched across any spatial configuration. This is what allowed him to vault the irregular shaped curving bays of the Saint-Denis choir. So long as each rib arch is stable, they don't have to conform to a specific angular arrangement.

Plan of the irregular-shaped bays in the choir

And the irregular-configured ribs used to vault them.

But Saint-Denis is an introduction. The final piece of the Gothic puzzle has to wait a few decades until the the new pointed rib vault stained glass system was used to build an entire church. This was the birth of the Gothic cathedral - first seen at Notre-Dame in Paris. But scaling Suger's style up to this size required a new innovation.

Cathedral of Notre-Dame, 1163-1345, Paris.

Notre-Dame is relatively small compared to later cathedrals, but a marvel of proportion and symmetry. Because it took so long to build there are different phases of Gothic style present. The facade was mostly finished by 1208, but construction continued on it until 1240.

The pointed arches are visible, and the thick verticals dividing the facade buttress the vaults supporting the towers.

Suger's choir was small enough not to face the challenges of extending the ribbed vaults and narrow piers to the full height of a big building. Even with pointed arches and lighter vaulting materials the outward pressure on such high walls would preclude big windows. But thickening the supports into buttresses like the ones on the facade would create a tunnel-effect around the windows that would block the light.

The solution was the flying buttress.

|

Flying buttresses along the nave wall of Notre-Dame

|

These were essentially solid towers that were moved away from the wall, with arched "bridges" that met the exterior at the points opposite the base of the interior ribs. They created localized counter-pressure at the points where the lateral force was greatest and prevented the walls from buckling outward. The whole structure was locked into stable static balance leaving thin walls to let in the maximum amount of light.

View of the buttresses "flying" over the roof of the lower side aisle to counter the outward thrust of the nave roof rib vaults. The big clerestory windows in-between are unobstructed by a thick wall.

And a cut-away diagram showing the parts of a cathedral and the intersection of flying buttresses and rib vaults.

Flying buttressing makes the exterior look more like an exo-skeleton because it moves the support to the outside of the building. It's easy to see in this aerial view of Notre-Dame, with the buttresses running all around.

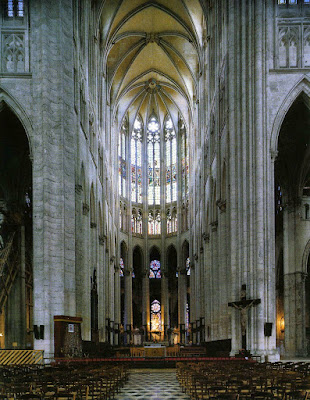

But it allowed the interior to look like a miracle - a smooth, rising, series of supports holding a canopy-like roof over big stained glass windows. Aesthetically, the flow from the supports into the ribbed vaults create a feeling of soaring unity that is accentuated by the pointed arches.

Notre-Dame is modest by later Gothic standards, but it established a template and proof of concept - Suger's choir could be scaled up into a full-sized cathedral. The result - perfect harmony of structure and aesthetic bathed in colored light - was a point of departure.

And a good shot of the vaulting and sense of verticality from below. It's easiest to see how the rib vaults create curtain walls for windows from this angle.

These are the fundamentals of the Gothic - pointed arches, rib vaults, and flying buttresses working togeather to open space for huge stained glass windows. A perfect unity of structure and aesthetics that realized Suger's dream of turning the church into a nearly supernatural glimpse of divine glory. And once the basics were worked out, Gothic architecture is a the history of refinement and adaptation across Europe.

Builders become more skilled and ambitious - raising the roofs ever higher while opening space for larger and larger windows.

Relative sizes of four Gothic cathedrals in chronological order showing the move towards bigger and lighter. Beauvais was never finished because the vaults were unstable.

Chartres Cathedral is a bit bigger than Notre-Dame and was built much more quickly, giving it a greater sense of unity. The North tower was rebuilt in the early 16th century in the late Flamboyant style of Gothic, so it doesn't match. Otherwise it is probably the most consistent in style. It also has the largest percentage of it's original stained glass surviving, making it a treasure. Chartres more than the more experimental Notre-Dame represents the beginning of what is known as the mature or High Gothic, and provided a template for the rest of the High Gothic trio in the 13th century: Reims and Amiens Cathedrals.

|

Chartres Cathedral, 1194-1220, Chartres, France with a good view of the flying buttresses.

|

Looking up into the vaults of Chartres shows the bigger windows.

The six-part vaults of Notre-Dame have also been replaced with a four-part or quadrapartite version that is simpler and more harmonious.

Chartre's windows are famous for the quality of their colors. Blues in particular.

But the real marvel of Gothic stained glass were the huge rose windows that could take up entire end walls. The most spectacular were found on transepts - the smaller spaces that intersected the nave to make a cross shape.

Plan of Chartres with the main parts of a cathedral marked out. The south transept is the projection off the bottom side.

South transept of Chartres from the exterior. You can see the big round south rose window spanning the entire space between the roof vaults. The ribs are marked on the plan showing that the space in-between is non-load bearing curtain wall and free to be used as a window.

The view from the inside is spectacular.

South Rose Window, Chartres Cathedral from around 1224. It is roughly 35 feet across.

A detail of the glass. The frame is made of cut stone.

Unfinished Beauvais has the highest vaults of any French cathedral, but collapses and overall instability ended construction with the transepts. The choir was built in the 13th century and the transepts in the 16th, but the collapse of a planned 502 foot tower ended construction for good.

Beauvais Cathedral, 1225-1232 and 1238-1284; 1500-1548, Beauvais, France.

The cathedral as it looks today, showing the 16th-century south transept and the choir and apse with towering flying buttresses.

The plan shows the 13th- century construction in black, the 16th-century parts in heavy gray and the unbuilt plan in light gray.

The view into the 13th-century choir at Beauvais.

The view from below shows the incredible height and the limits of French Gothic vaulting to make stone float on glass.

The problem with describing and classifying the Gothic is that is spread and changed in different times and places. The English Gothic is quite different from the French that inspired it. Even some of the buildings seen here were built over long periods with additions at later dates. Saint-Denis and Notre-Dame both have major sections that belong to different stylistic phases in one place. Plus the different phases of Gothic aren't precisely definable chronologically - changes happen in some places while the older style is still being used in others. They're more tendencies than hard distinctions. But they are tendencies, and we can briefly identify a few broad characteristics before wrapping this up.

The next phase in France is known as the Rayonnant Gothic. It appears between roughly 1240 and 1350, overlapping with the earlier High Gothic of 1200-1280. It more or less corresponds with the English Decorated Style, though that looks different and comes later.

The term comes from the French word for radiating and was first used in the 19th century when historians were trying to build a taxonomy of Gothic architecture off the design of windows. The Rayonnant was named for shape of the spectacular new kind of rose windows that began appearing at this time.

Like the north rose window of Notre Dame de Paris, 1250-60

Obviously there's more to it, but compare this to the Chartres rose above and the difference is visible. The "spokes" radiate out much more clearly - Rayonnant - and the glass takes up a greater percentage of the wall space. The stone dividers are smaller and the glass fills out the bottom corners too.

The Rayonnant is marked by a move away from the emphasis on monumental and rationally-ordered masses that we see in the High Gothic for a focus on linear decoration - both on two-dimensional surfaces and in space. In both cases, the effect is to obscure the massing of the building itself.

This can be seen on the outside of the north transept at Notre-Dame, where the above window is. It was built in a later stage than the nave we looked at above and is a good example of early Rayonnant. Compare it to the older main facade and you can see how the clear sense ordered massing has been replaced by a planar flatness and linear decorative elements.

Even the gable above the portal on the transept is like a flat plane suspended in front of the facade, and all available space is filled with either windows or linear elements that look like they came from the windows. The impressions is one of less depth, less obvious structural logic, and especially less mass or weight.

It's even more obvious it its mature form, like at Saint-Urbain de Troyes. Here structural elements are hidden beneath decorative stone strips, the porch extends like a screen, and the window structure repeats on the facade:

|

Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes, facade built 1262-86

|

The development of the Rayonnant was triggered by an evolution in window design - a reminder that the stained glass window was central to the Gothic structurally and aesthetically. The earlier Gothic windows were made with a technique called plate tracery. Tracery is the term for the stone strips that support and divide the windows into patterned sections and can also be applied to other surfaces on a Rayonnant facade.

Western rose window, 1215, Chartres Cathedral.

Plate tracery - the tracery surrounding the lights - the glass part of a window that lets the light in - is relatively thick and heavy. It gets its name because the window looks like it was cut out of a stone plate.

The Rayonnant saw the development of a lighter, more delicate, and more flexible bar tracery. Here, the lights are separated by individually cut stone bars. It's first used in a significant way at the Reims and Amiens Cathedrals.

Max Švabinský, Last Judgment window, 1937, St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague

Bar tracery - the tracery is a web of bars that can be organized into more complex patterns while leaving more of the window opening free for glass.

This is a modern window, but an excellent illustration of the flexibility and openness of bar tracery.

The switch to bar tracery allowed the huge walls of glass that defined the Rayonnant and seemed to dissolve the masses of the Gothic building. And the tracery strips could be applied beyond the windows - to make patterns on the facades like on the the north transept of Notre-Dame and to create screens above the entries like at Saint-Urbain de Troyes.

When the tracery is applied to a wall it's called blind tracery because the spaces can't be seen through - they're just surface patterns. When it's like a web or screen it's called open tracery for obvious reasons.

Blind tracery in the 13th-century tympanum of the western portal of Saint-Urban, Troyes, France

13th-century open tracery at Rouen Cathedral

The technology of the Gothic didn't change with the switch from High to Rayonnant other than the new bar tracery windows - the buildings were still built with rib vaults, pointed arches, and flying buttresses as needed. It's an aesthetic shift. The builders grew more confident opening larger spaces with the same techniques and bar tracery turned these into radiant glass walls. Carrying the tracery beyond the windows onto facades and into open space lightened the appearance of the buildings into linear ornamental displays.

On the interiors, the Rayonnant transformation is dramatic. Here again Saint-Denis is a pioneer. Although Suger was long dead, his renovation and rebuilding plan lived on, and in the 1230s, the nave, transepts, and upper choir were replaced in the radiant new style.

The entire upper wall had been flattened out and replaced with stained glass. There's a spectacular rose like the one at Notre-Dame, and the bar tracery in the pointed windows continues down past them to divide the arches in the gallery below. This is that same Rayonnant emphasis on surface ornament over mass that we saw on the outside taken inside.

Looking into the new choir, the contrast with Suger's surviving ambulatory is clear.

Bar tracery and glazed triforium in nave of St Denis (19th-century replacements). His smaller windows and early rib vaults seem dark and heavy in comparison. But if you look closely. you'll see that the structural elements haven't changed. Just the application.

One of the Rayonnant innovations was figuring out how to glaze the walls of the triforium. That's that gallery between the clerestory and the lower arcade that corresponded to the pitched roof over the aisles. Because it was the back of a right-angled triangle with the pitched rood as the hypotenuse, it was dark.

Here it is on a diagram.

The triforium was usually used as a secondary passageway and gallery since it wasn't practical for much else.

And as it appears in Chartres.

Aesthetically it created a dark band between the lights of the clerestory and the side aisles in the High Gothic.

Saint-Denis used a new roofing method that moved water away in concealed channels and allowed for windows to be opened along the triforium wall. The relatively small openings and heavy supports were replaced with slender bar tracery. The dark band became another row of light, further lightening the interior.

This also a good view to show how much the Rayonnant flattened out the interior as well. The effect is 2d decoration on an thin wall. When the Gothic is referred to a sort of skeletal building system, it's clear here.

Close-up of the clerestory and triforium windows with elaborate bar tracery frames and the thin verticals connecting the two levels.

So to generalize, the Rayonnant differs from the High Gothic for its appearance of relative weightlessness, flatness, and linear verticality. These are dramatic, but mainly aesthetic. The structural differences are comparatively minor. The basic building principles remain the same - pointed rib vaults and flying buttresses in suspension that open space for glassed curtain walls. The invention of bar tracery and refinements in roofing and water management allowed for bigger windows and more light within those basic parameters. The Rayonnant is distinguished from the High because it looks so different, but it's more accurate to call it an evolution in style rather than a transformation.

And no where do we see this immaterial appearence more clearly than at the Sainte Chapelle in Paris.

Thomas de Cormont, Jean de Chelles or Robert de Luzarches, Sainte-Chapelle, 1241-1248, Paris

This isn't a cathedral - it's much smaller, which is why you don't see flying buttresses. The roof was light enough that fixed buttresses would do. It was built as a reliquary - a place to house precious relics acquired by Saint King Louis IX, the only canonized king of France.

The rose window on the end was added around 1490 and is in a different style than the Rayonnant. It's Flamboyant Gothic, the last stage that we'll look at in the next post.

It's the interior of the Saint-Chapelle that makes it a true artistic wonder of the West. The upper nave is a single rib vaulted space with the walls looking like an unbroken ring of glass. There are 15 large windows not counting the later rose, each almost 50 feet high. Together, there are over 1100 panels telling the history of the world through the Old and New Testaments and the story of the relics up to the time they got to Paris.

The inside view. The pointed rib vaults are gilded, marking out the clear structural skeleton as they continue down onto the bundled columns. It really is a cage of glass - impossibly light and airy for a stone building.

The contrast with the outside view is striking.

Looking up into the vaults reveals the Rayonnant at its most radiant. The flame-like appearance of the Flamboyant rose actually clashes with the harmonious linear immateriality of the rest of the structure. As we've seen, Gothic builders cared less about stylistic consistency than using the latest fashion. This is still a great picture of that perfect fusion of structure and aesthetics:

The lighting adds to the supernatural effect:

The experience is a visual symphony of colored light that shifts and changes with the times of the day

The effect of the Sainte-Chapelle in twilight is more somber and mysterious than the jewel-like illumination of midday.

And a final look up the windows, revealing that flat, linear, brilliant verticality that defined Rayonnant interiors. The walls just seem to disappear in a haze of light and color:

The Rayonnant spread around Europe, like the Gothic in general. One of the most impressive examples of its mature form is in Germany. Cologne Cathedral was based on the design of Amiens and started in 1248, but work fizzled out in 1473 with only the choir and transepts finished. Construction didn't resume in a serious way until it was inspired by Romantic fascination with nationalism and the Middle Ages in 1842. The original plans for the facade had been rediscovered, adding further impetus. The cathedral was finally finished in 1880 and followed the medieval appearance, although modern building techniques were used. The decorative Rayonnant immateriality is clear it its towering form.

Cologne Cathedral, 1248-1880, Cologne, Germany

The huge Rayonnant facade is a 19th-century creation, but faithful to the 13th-century plan. All the features are present - the downplaying of structural clarity, emphasis on decoration, verticality, and liberal use of bar tracery in the windows and elsewhere.

On the interior, Cologne's medieval Rayonnant choir is a masterpiece of the style. The developments we say at Saint-Denis expanded to an even larger size.

The rib vaults open space for enormous clerestory windows, and the glazed triforium is striking. Cologne is very tall, but the verticality of the window shapes and the arrangement of the bar tracery accentuates that even further.

A closer look the clerestory and the triforium show that flat, immaterial feel that indicated the Rayonnant.

As the 14th century progressed, the Rayonnant gradually evolved into the final phase: the Flamboyant style. But this has been a long post - turns out that the pictures stretch it more than we thought. But this covers the essentials of the Gothic as a concept - where the vaulting came from, how it evolved into the Gothic rib vault and flying buttress system, and the two main stylistic forms - High and Rayonnant. We're going to stop here - if this post proves interesting to readers, we'll do a part two breaking down the Flanboyant Gothic and looking at the unique English versions. They come from the French, but quickly develop their own forms. We also need to look at Gothic art and how it leads into the Renaissance.

To relate this back to the roots of the West, we need to consider the relationship between art and Logos. We often say that Beauty is what the Good and the True look like, and the Good and the True are knowable to us through Logos. What makes the Gothic so special is the way that logic on different levels come together - all three levels of our ontological hierarchy to be exact. Click for the main post where we work this out.

The structural logic is material-level logos. Using the physics of vaulting with the material qualities of the stone and glass, Gothic builders created beautiful aesthetic forms that looked the way they did for practical reasons. Pointed arches are stronger. Ribbed vaults are lighter. Flying buttresses make walls thinner. Together they make the big windows possible. For all the mystical beauty of the Gothic, its parts wear their function openly.

The aesthetic beauty of the structure is abstract level logos. Light and color to create an almost supernatural environment that is paradoxically based on structural logic, but pulls mind and soul away from the material. The Rayonnant in particular seems to realize Suger's dream of heaven on earth and bring you closest to immaterial things.

Together material and abstract point towards the logos of ultimate reality - capital L Logos. This is the true subject of all the structure and aesthetic and the inspiration for the sometimes centuries of effort that went into these.

The skilled designers and craftsmen that built the cathedrals were highly sought-after and well compensated professionals. Yet they spent their lives on projects knowing that they would likely never see them finished. Generations could apply their talents to one site, accumulating efforts to the glory of God.

This is not to say that the Gothic is the "correct" form of art. Art is techne plus episteme, and techne takes different forms in different contexts.

But it is a correct form of art - the perfect synthesis of techne and episteme in the service of phronesis. Click for the application of our Greek terms to the arts of the West.

The beauty of their truth blazes from their soaring windows. Logos drips from them in colored rivulets.

There is much they can teach us.

No comments:

Post a Comment