If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right.

The last post left off with Brunelleschi’s introduction of a completely new architecture based on simplified Classical ideas. Now it is time to look more closely at invention of architectural theory in the Renaissance, not to rehash the standard academic narratives, but to better understand how the likes of Walter Gropius were tapped to set the course for building into the twenty-first century. Brunelleschi reframed architecture as an experience of transcendence defined in terms of simplicity and clarity, and the road from here to Le Corbusier is more direct than it first appears. The Renaissance was one of the defining events in shaping the Western tradition, and this has led to a tendency to place it on a pedestal historically, much like the Neoclassicists did with Periclean Athens. “Serious” criticism has tended to flow along drearily predictable anti-Western channels, looking to dilute the creativity of the period with tenuous “influences” that bear little resemblance to their supposed derivatives.

Giorgione, Castelfranco Madonna (Madonna and Child between St. Francis and St. Nicasius), 1503-1504, tempera on poplar, 200 x 152 cm, Castlefranco Veneto Cathedral

Globalist art "historians" will fixate on the Middle Eastern carpet hanging below the Madonna's throne as "evidence" of the Islamic "influence" on Renaissance art. The carpet is actually a sign of Venetian trading wealth, and is completely tangential to the significance of this picture.

Globalist art "historians" will fixate on the Middle Eastern carpet hanging below the Madonna's throne as "evidence" of the Islamic "influence" on Renaissance art. The carpet is actually a sign of Venetian trading wealth, and is completely tangential to the significance of this picture.

If we consider the historical record objectively, it is clear that Renaissance Florence, like Classical Athens, synthesized diverse elements into radically new aesthetic, epistemological, and moral structures of incalculable influence. Both were driven by (different) notions of intellectual progress and cultural improvement and are part of the sociological DNA that made possible the enormous technological innovations of the post-medieval West. But objectivity requires recognizing that the modern West contains ideological vulnerabilities that have left it open to corruption and distortion from the globalist left. This is the darker legacy of the Renaissance, and it must be confronted honestly if there is to be any sort of positive, organic cultural rejuvenation.

Leonardo, Vitruvian Man, circa 1490, 34.6 cm × 25.5 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

In one of the most famous images of the Renaissance, Leonardo captured the humanist notion of man as a cosmic microcosm, or expression of fundamental universal principles. We can see the harmonious relationship between the ideal human proportions and the basic elemental shapes of circle and square.

This is an early statement of what the Band calls secular transcendence, the empirical fallacy that finite humans can determine timeless, metaphysical Truths by reacting to their historical material circumstances.

In one of the most famous images of the Renaissance, Leonardo captured the humanist notion of man as a cosmic microcosm, or expression of fundamental universal principles. We can see the harmonious relationship between the ideal human proportions and the basic elemental shapes of circle and square.

This is an early statement of what the Band calls secular transcendence, the empirical fallacy that finite humans can determine timeless, metaphysical Truths by reacting to their historical material circumstances.

The role of theory in Brunelleschi’s architecture is an interesting one because it teeters on the edge of category error. Prior to Brunelleschi, “theory”, or a set of universal principles for correct artistic processes, really didn’t exist as a concept. A master mason was trained in techniques, and was able to provide clients with buildings that they found attractive, but they didn’t adhere to a set of external, idealized standards. Theory is an archetype of the philosophical bait and switch, because it is based on post-facto observations of recent practice but claims to be the guiding light. In short, theoretical “rules” are inductive abstractions posing as principles for deduction. Brunelleschi was inventing a new visual language, and had no close architectural priors to follow, although he did have his own guiding principles. It makes more sense to start by looking at his work empirically before moving to the later theorizing of Alberti.

On the simplest level, we can start to determine what was new about Brunelleschi by looking at how his buildings were put together.

Matthias of Arras, Peter Parler, and others, St. Vitus Cathedral, 1344-1929, Prague

Gothic aesthetics, as we saw, was derived from the vaults and pointed arches that made up the essential structural elements of the building. Matthias' original design for this Czech national treasure was French, but Parler devised the unique vaults. The fact that it took almost six hundred years to finish is another sign of the relationship between medieval architecture and national culture.

Brunelleschi’s approach is completely different. The last post looked closely at Santo Spirito because it made a good visual comparison with the churches of the Middle Ages, but even this building doesn’t give a full appreciation of his design philosophy. It reflected another aspect of his humanistic outlook – an interest in ancient forms – and followed the basic layout of an early Christian basilica with a flat roof and colonnaded nave. Any column or pier-based architecture lends itself to a modular appearance, since the supports tend to be evenly spaced. The same thing occurs in construction today: it is more efficient to work with standard material lengths.

Top: Plans for Notre-Dame in Paris, Reims, and Amiens Cathedrals

Bottom: Brunelleschi, plans for Santo Spirito and San Lorenzo, Florence

Plans are useful for identifying the basic layout of a building. Here, solid lines are walls, columns and other supports, and faint ones are vaults (arches, domes, etc.). The modular design is apparent all of them, but Brunelleschi is more rigorous in setting the 1:1 proportions of the small square bays as the key to the whole building. The exact same rigid proportionality is seen in his plan for San Lorenzo.

The problem with thinking about Brunelleschi in terms of an overriding theory is that he is the first architect since antiquity to subordinate his designs to a higher set of governing principles in this way. He is introducing and inventing theoretical architecture, rather than applying it, and we can see him figuring out what works in his actual projects.

Brunelleschi, Ospedale degli Innocenti, 1419-27, Florence

The foundling hospital was Brunelleschi's first attempt at a simple geometric architecture. His colonnade anticipated Santo Spirito with square domical vaults (these are vaults that look like a squared-off area of a sphere). His plan was based on the simplest possible ratios, with the width and height of each bay equal. This made the arches perfect half circles, and the volume of each bay below the arches a perfect cube. The dimensions follow 1:1 and 1:2 relationships.

The problem was aesthetic. These square bays look too wide for their height when compared with ancient colonnades, making the columns look spindly. "Perfect" geometry is an intellectual ideal, but is visually displeasing. Recognizing this, Brunelleschi returned to more traditional proportions in his later colonnades like Santo Spirito and San Lorenzo.

On the simplest level, we can start to determine what was new about Brunelleschi by looking at how his buildings were put together.

Matthias of Arras, Peter Parler, and others, St. Vitus Cathedral, 1344-1929, Prague

Gothic aesthetics, as we saw, was derived from the vaults and pointed arches that made up the essential structural elements of the building. Matthias' original design for this Czech national treasure was French, but Parler devised the unique vaults. The fact that it took almost six hundred years to finish is another sign of the relationship between medieval architecture and national culture.

Brunelleschi’s approach is completely different. The last post looked closely at Santo Spirito because it made a good visual comparison with the churches of the Middle Ages, but even this building doesn’t give a full appreciation of his design philosophy. It reflected another aspect of his humanistic outlook – an interest in ancient forms – and followed the basic layout of an early Christian basilica with a flat roof and colonnaded nave. Any column or pier-based architecture lends itself to a modular appearance, since the supports tend to be evenly spaced. The same thing occurs in construction today: it is more efficient to work with standard material lengths.

Top: Plans for Notre-Dame in Paris, Reims, and Amiens Cathedrals

Bottom: Brunelleschi, plans for Santo Spirito and San Lorenzo, Florence

Plans are useful for identifying the basic layout of a building. Here, solid lines are walls, columns and other supports, and faint ones are vaults (arches, domes, etc.). The modular design is apparent all of them, but Brunelleschi is more rigorous in setting the 1:1 proportions of the small square bays as the key to the whole building. The exact same rigid proportionality is seen in his plan for San Lorenzo.

The notion of strict, consistent rules that supersede individual design circumstances IS the basis of theory.

The problem with thinking about Brunelleschi in terms of an overriding theory is that he is the first architect since antiquity to subordinate his designs to a higher set of governing principles in this way. He is introducing and inventing theoretical architecture, rather than applying it, and we can see him figuring out what works in his actual projects.

Brunelleschi, Ospedale degli Innocenti, 1419-27, Florence

The foundling hospital was Brunelleschi's first attempt at a simple geometric architecture. His colonnade anticipated Santo Spirito with square domical vaults (these are vaults that look like a squared-off area of a sphere). His plan was based on the simplest possible ratios, with the width and height of each bay equal. This made the arches perfect half circles, and the volume of each bay below the arches a perfect cube. The dimensions follow 1:1 and 1:2 relationships.

The problem was aesthetic. These square bays look too wide for their height when compared with ancient colonnades, making the columns look spindly. "Perfect" geometry is an intellectual ideal, but is visually displeasing. Recognizing this, Brunelleschi returned to more traditional proportions in his later colonnades like Santo Spirito and San Lorenzo.

A bay in Santo Spirito next to one from the Ospedale degli Innocenti. Underneath is a diagram of the proportions at San Lorenzo. We can see that the older square is extended by something resembling a root 2 rectangle.

Brunelleschi sacrificed perfect geometry for ratios that were messier but more visually pleasing, and much closer to the organic dimensions of the Gothic Cathedrals. There is a lesson here.

Abstract perfection is an objective intellectual ideal that may not be compatible with human subjectivity.

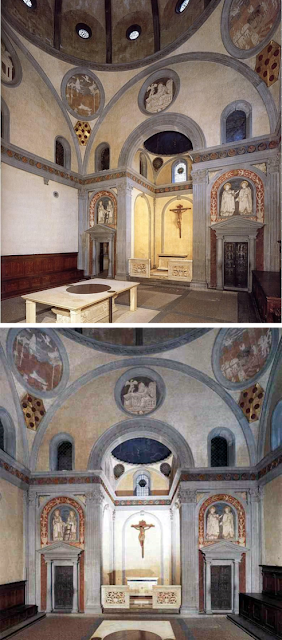

Brunelleschi never wrote an account of his design philosophy, meaning we have to look at his works to get a better sense of his principles. These are clearest in his smaller projects around San Lorenzo, were he was not following a clear historical type like a basilica. The Old Sacristy and Pazzi Chapel are small, contained spaces that clarify the importance of geometry and ornament in his thought.

Brunelleschi, Sagrestia Vecchia (Old Sacristy), 1421-40, San Lorenzo, Florence

The cubic structure is similar to one of the bays in the Ospedale degli Innocenti arcade, although here the dome is also a perfect half circle as well. The elementary geometry is clear in the diagrams (section and plan) and the view into the dome. The entablature around the room bisects the cube, meaning the proportions are based around clear and simple 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3 relationships.

The ceiling is a ribbed dome on pendentives. In non-technical terms, a ribbed dome is supported by spoke-like arches, leaving the spaces in-between non-load bearing and able to have windows. Pendentives are the three-cornered portions of a sphere that the dome sits on, transitioning from the square room to its round base. This technique was first seen in the Hagia Sophia (532-27) in Constantinople.

The simple proportions are obvious at a glance. Brunelleschi used a personalized color scheme based on Florentine tradition, to mark out the decoration. The decorative panels were added later, since he wanted the ornament to be kept to a minimum, and didn't approve of paintings and sculptures.

What is notable is how the relationship between structure and ornament has changed. The Old Sacristy is an example of wall architecture, meaning that the structure and shape are determined by relatively solid planar walls. The decoration is then applied to this simple underlying shape to highlight key features and create visual interest. It is true that the decoration reflects the structure, but it does so in an inessential way, in that removing the decorative elements would have no impact on the integrity of the building. They are basically "drawn" onto a polygonal surface.

The most important new development when compared to Gothic architecture is the complete separation of structure and ornament. The pointed arches and ribbed vaults at the Sainte-Chapelle were structural. The Classical motifs applied by Brunelleschi weren't.

From a practical perspective, who cares if form and decoration are unified, but from a theoretical one, thinking of them seperately is a necessary precursor to Modernism.On a communicative level, it is easiest to think of the difference between the two through a musical analogy.

Male Choir of St. Ivan Rilsky, Dupnitsa, Bulgaria

Gothic architecture brings ornament and structure together into a seamless, if complex, whole, akin to the blended voices in polyphonic music.

Led Zeppelin, Palais des Sports, Paris, 1973 ©Barrie Wentzell

Brunelleschi "draws" with ornament over a simple geometric substructure which is more like a soloist backed by a rhythm section in a rock or jazz band.

So we have to think of Brunelleschi as communicating on two different levels - structurally and ornamentally – to understand what he is attempting to express.The structural geometry of the Old Sacristy is remarkably simple: a cube topped by a semi-spherical dome. Just looking at the interior of the Old Sacristy makes it obvious that Brunelleschi sought a clear, rational, harmony, especially when compared to the Gothic Duomo which he recently finished.

Brunelleschi, Pazzi Chapel, c. 1429-61, Santa Croce, Florence

His domes are rib vaulted - exactly the same technology used by medieval builders, but look at the clarity. The only decorative elements highlight the simple structural geometry.

Returning to the musical analogy, the shape of the structure establishes a basis in pure geometric simplicity while the ornament is freer to express slightly more complex relationships for aesthetic purposes. To Brunelleschi, like many Renaissance thinkers, perfection was conceived of in terms of simplicity, but he recognized that such purified abstract forms are off-putting to most visitors. So the ornament mediates between the absolute geometry of the structure and the subjectivity of the individual with decorations are tasteful and proportioned in appearance. Structure and ornament are different, but they work harmoniously to create an accessible experience of transcendence. There are mathematical principles here, but they do not rise to the level of absolute governing theory over the entire design.

Link Arkitektur, Aalgaard Church, 2015, near Stavanger, Norway

Because nothing speaks to the transcendence of the sacred like colorless blobs and plastic chairs.

The role of theory in Brunelleschi's architecture is complicated by the fact that he more or less invented the idea of a theoretical approach to architecture. He wasn't applying a pre-existing corpus of ideas to his designs like a more recent practitioner would because the very notion that there was a corpus didn't exist yet. Brunelleschi is important for introducing the idea that an architect should subordinate his ideas to higher principles, then attempting to work out the application of these principles in practice. What elevates Brunelleschi from eccentric geometer to theoretical pioneer is the codification of his basic principles by his younger acquaintance (Brunelleschi was notoriously antisocial and really doesn't appear to have had friends) and "founder" of art theory, Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72).

Alberti

Alberti, Self-portrait medallion, circa 1435, bronze, 20.1 × 13.6 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, photo: I, Sailko

Alberti was a promising humanist scholar before problems with his eyesight made a career spent poring over manuscripts in poor lighting impossible. Switching his focus to the visual arts, he bridged the gap between art and humanism and became the most influential architect and theorist of the fifteenth century.

Profile portrait medallions were popular among early Renaissance humanists because they had ancient Roman connotations. Alberti's emblem, a winged eye that represented the search for knowledge, is visible under his chin. This sort of personal sign was also typical of humanists.

Alberti was a humanist scholar in the truest sense of the word with writings that span a range of topics, and is considered a pioneering figure in cryptography. He is best known for three treatises on the visual arts that are among the most influential art writings of all time. His book on architecture, De Re Aedificatoria (1452), was the first of its kind since antiquity, and followed a Roman humanists' view of antiquity with a heavy reliance on Virtuvius. But Alberti was not a revivalist who attempted to copy ancient models faithfully; his goal was to derive theoretical principles from ancient buildings and texts then adapt them to contemporary circumstances.

Alberti, Santa Maria Novella, 1448–70, Florence

Here we see Alberti attempting to apply a Classical temple front to a church. He accommodates the irregular shape by dividing the facade into two registers or levels and turns the top story into a pedimented temple facade. He then smooths the transition between the two with big volutes. The color scheme reflects the same Florentine tradition that inspired the decoration of the cathedral. The underlying substructure is Classical, but the appearance is expresses subjective specifics.

From the side, it is clear that Alberti's facade is just that; a facade. It is an excellent visual metaphor for theoretical architecture as an intellectualized abstraction applied to a practical structure.

Real revival combines theory and practice in a distinct way, since the underlying theoretical principle – the faithful recreation of ancient forms – is indistinguishable from the practical activity of studying and replicating ancient forms. Alberti studied antiquity, both Roman ruins, but more importantly, ancient texts, then abstracted a theoretical framework from them that is not faithfully reflected in his own practice. His theory is not a summation of ancient building methods or a set of blueprints for future designers. This is what makes it unique. It is more of a philosophical reflection on the nature of architecture with the intention of establishing a set of what would be called first principles in the sciences today. Alberti's theory is an architectural ideal based on his own study of ancient buildings and texts and filtered through the ideological prism of his humanist preconceptions about antiquity.

Alberti, Basilica of Sant’Andrea, Mantua, Italy, 1472-90

Here, Alberti attempts another adaptation of a temple front. Although it is an example of Renaissance wall architecture, it uses pilasters to suggest a Classical colonnade. The proportions recall Brunelleschi by following a perfect square, but the facade isn't plain, and Alberti uses deep recesses to make it seem more expressive. Perfect geometric form provides the substructure, and decorative features derived from antiquity make it more humanly appealing without hiding the underlying ideal.

The spacious interior is also harmoniously proportioned and heavily decorated. The large coffered barrel vaults and superficial features like the Corinthian pilasters are ancient, but they are assembled in a completely original way.

Classical architecture and ideal proportions are the theoretical substructure, while ornament allows for individialized expression.

Nave wall of Alberti's Sant'Andrea, Mantua

Basilica of Maxentius, 308-312, Rome

An example of "theoretical" classical inspiration. The idea of coffered barrel vaults came from an ancient structure completed by Constantine, but the specifics of the appearance - the proportions and decoration - are Alberti's own.

The key difference between Alberti and Brunelleschi in terms of historiography is that Alberti codifies this approach in writing and lays down a set of theoretical precepts in treatise form. His humanist background is integral to this for several reasons, which are worth listing to clarify the inputs actually shaped the appearance of "objective" art theory.

Despite its claims of uncovering new paths to truth, humanism is best thought of as a reactive movement, in that it took on forms that in reaction to the dominant culture that it was challenging. This means that the reasons for its "innovations" can generally be found in pre-existing social and epistemological assumptions. Alberti's desire to elevate the status of the visual artist from practical craftsman to theory-based intellectual was typical of humanists, and is an example of a "new" idea that is shaped by the older notions that it seeks to replace.

Vitruvius Pollio, Matteo Felice (illuminator), De architectura, circa 1480, parchment, 293 x 210 mm, Universitat de València, Biblioteca Històrica BH Ms. 727

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, presentation copy on parchment, pub. Nicolaus Jenson, Venice, 1476, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Arch. G b.6

Woodcut showing Pythagoras with bells, glass harmonica, monochord and pipes tuned to Pythagorean harmony, woodcut from Theorica musicae by Franchino Gaffurio, 1492

The new humanist notion of artist was based on ancient authors like Pliny who presented painters and sculptors as important individuals worthy of remembrance and judged them on fixed standards. This was connected to a pagan notion of fame as a form of immortality – your name lives on – that only works when a society considers worldly accomplishments worthy of memorializing. For Alberti, this must have been intoxicating. How could someone like Brunelleschi, whose extraordinary ingenuity brought glory to Florence, not be ranked higher than a blacksmith? But for this to happen, the traditional concept of "art" had to be rethought.

Sandro Botticelli, A Young Man Being Introduced to the Seven Liberal Arts, 1483-86, fresco, detached and mounted on canvas, 237 cm × 269 cm, Louvre, Paris

In the Middle Ages, an “Art” was an intellectual field founded on objective rules - first principles or theory - and didn’t involve manual labor. The seven liberal arts were grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic (the trivium) and geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy (the quadrivium). Music was among the mathematical arts because the harmonic scale was based on mathematical ratios.

Traditionally, all the visual arts were considered skilled crafts, meaning that they were not based in unchanging theoretical principles like the arts. Practitioners of dialectic and geometry addressed the same issues anywhere, but artists were trained by apprenticeship in individual workshops and catered to local taste. There were common assumptions about what images were and what they were for, but there was not the expectation that visual arts followed objective principles like logic. Artists could be successful, and even admired, but they were not intellectuals in the Liberal Arts sense.

The Tower of Babel, detail from the Crusader Bible (Morgan Picture Bible), 1240s, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, Ms M. 638, f. 3r.

Medieval builders, including a human-powered hoist.

The Liberal Arts were based on ancient ideas originally, but evolved into a specifically medieval curriculum during the Middle Ages. To the humanists, this meant that the source material was tainted; remember that humanist scholarship was oriented towards restoring the purity of ancient texts, and the older a source, the better. The Nine Muses, Greco-Roman goddesses of the arts, differ from the medieval seven, and had a "purer" classical pedigree if not the deep tradition.

Baldassare Peruzzi, Apollo and the Muses, 1514-23, oil on wood, 35 x 78 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence

The identities of the Muses developed over time, but this is a pretty standard line-up: Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (history), Erato (lyric & love poetry), Euterpe (music), Melpomene (tragedy), Polymnia (sacred poetry, hymns), Terpsichore (dancing & choral song), Thalia (comedy), Urania (astronomy). The last, Astronomy, overlaps directly with the Seven Liberal Arts.

In the Renaissance, the precise number of Liberal Arts loosens as humanists elevate history and poetry to the level of art. This was possible, they argued, because these arts, as much as any of the seven, reveal universal truths. Though not specifically represented by a Muse, the visual arts sneak in on poetic and historical grounds, as analogous symbolic purveyors of higher knowledge. This is an early example of the academic bait and switch, the depressingly common tactic of presenting something as other than what it is. But the consequences are far more pervasive than your average scholarly debate.

Pay attention to the epistemological change. The medieval arts tradition was a narrow sphere of intellectual activity based on perceived objective standards beyond the personal creativity of an individual practitioner. The idea of separate "fine" arts is alien to this thinking.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Gates of Parardise, 1425–52, gilt bronze, Florence Baptistry; originals, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

Both Brunelleschi and his arch-rival Ghiberti were trained as goldsmiths, a skilled craft that was not considered an "art" either in the Middle Ages or the theory that came out of the Renaissance. The notion that painting, sculpture, and architecture were somehow different from other types of visual culture had not yet crystalized in early fifteenth-century Florence, and goldsmith training was a good way to learn design and refined technical skills.

Ghiberti's second set of doors for the Florence Baptistry has been considered a masterpiece of Renaissance art since its unveiling.

In medieval terms, what we think of as the visual, historical, or language arts correctly belong to the subjective realm of human activity. This is empirically sensible; you can slop paint around any way you want and you'll still get a "painting", even if not a very good one.

Joseph Noel

Paton, Dante Meditating the Episode of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta,

oil on canvas, 101 x 89 cm, Bury Art Museum, Manchester

Franz Kline,

Black Reflections, 1959, oil and pasted paper on paper, mounted on Masonite, 48.3

x 49.2 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

These are obviously both paintings, in that the are applications of paint to a rectangular surface. But they are so different in content and appearance that any possibility of actual objective guiding principles is disproven. What possible set of rules, other than simple material facts, could possibly account for both of these?

Also note that only one of these is in a "world-class" art museum.

One does not have the same symbolic freedom as Paton and Kline in math or logic, where the fields are necessary expressions of their founding principles. A mathematical solution or philosophical argument that doesn't conform to the rules of the art is an incoherent collection of symbols. A proof, syllogism, or set of astronomical calculations can be determined correct or incorrect on purely objective grounds. A string of random numbers and operations is simply not mathematics. Paton and Kline's works are both correctly classified as paintings, which means that their differences are more subjective assessments of how good they are. Good and bad execution are simply not the same thing as correct and incorrect answers. By elevating art forms to the level of theoretical objectivity, Renaissance humanists muddied the difference between good/bad and correct/incorrect distinctions. This objective/subjective confusion is something that all forms of the left have used to advance political aims. It cannot be stated enough that:

This is such an important shift because claiming objectivity for things that are obviously subjective expressions changed Western epistemology on a basic level. There are no standards, not even a simple mathematical foundation, that cannot be subverted and twisted into its opposite. Consider how effective the left has been in hollowing out institutions - media, government, education, etc. - and turning them into broadcasters of toxic, intellectually bankrupt ideology.

Winners always wrote history and commissioned grand monuments to assert a certain point of view, but Renaissance humanists provided justification for the practice on theoretical grounds for the first time. Most are unaware that humanist historiography was fundamentally different from ours. We tend to think of historians as aiming to recount the past as accurately as possible, and when the story is changed, it's because new information has come to light to make the picture a bit clearer. We know that in more recent times, Marxists and Postmodernists openly lie about history to attack Western culture and accrue power, but Renaissance humanists argued that history should deviate from specific facts in order to more clearly illustrate a higher truth or principle. This can be thought of as the first intellectual justification for propaganda and thought control in the West, since we all know that any human attempt to establish an objective "truth" is never more than projected ideology.

This brings us to the introduction of a new line of inquiry that has grown out of the Band, which will appear when appropriate under this heading:

It's becoming obvious that the current Postmodern globalist cultural cesspool has very deep roots in Western intellectual history. As the Band moves into more culturally-focused topics, this threads will be identified under this Roots of Globalism symbol. As some point, there will be enough of them to observe larger patterns. In this case, Renaissance humanists introduce a specific form of philosophical bait and switch that blurs epistemological clarity and brings about cultural change through the back door.

Epistemology and Culture

The Band was always interested in culture and history, but had to spend time on philosophical subjects to introduce the necessary concepts for understanding Postmodernism. Historiography, or how history is conceived and structured, is one of these terms, and epistemology, or how we know things, is another. It is helpful to understand the relationship between epistemology and knowledge through the artistic metaphor of form and content, or what something is/looks like, and what is communicates. In this metaphor, the specific facts and narratives that comprise our knowledge would be the "content", while epistemology is the "form"; how that knowledge is created, how we know and learn, what authorities we accept as truth, etc.

Epistemological confessional: The Band's empirical epistemology was summed up in a diagram from an earlier post as navigating the subjective experience of an objective world, while recognizing that transcendentals are beyond objective knowledge. There is a parallel between Piercian semiotics and Aristotelian ontology that comes from this basis in reality. As finite beings, there are things that simply exceed our perception or comprehension.

Form and Content: The Philosophical Bait and Switch

This form/content distinction helps clarify how change agents like humanists or Postmodernists drive a cultural agenda. The pair of paintings that we looked at earlier illustrates this:

Both are applications of paint to a rectangular surface that are displayed and discussed in "art world" venues. On this level, they are examples of the same thing. But look at what they depict and consider the cultural expectations and assumptions that inform the two. In terms of what painting is supposed to do and its relationship to society, the two are utterly different. This allows critics and "historians" to claim that their paint splatters and "provocations" are an organic evolution within the cultural space that most purely expresses the values of a society. But the "meaning" of the painting - what it represents on every level - has become diametrically opposed. Neither Paton, nor anyone before him, would consider the Kline a work of art, even if you filled them in completely on the entire body of theory claiming that it is.

Cy Twombly at the Tate Modern in London. It is unclear whether the small concrete slabs in the foreground are "sculpture" or part of renovation work on the building. Ask yourself if you or anyone you know would want these huge splatters if they weren't promoted by culture authorities and worth absurd money on the art market (Twombly's current auction high is $70.5 million). What possible cultural or personal purpose could they serve beyond the gullibility of the wealthy to artsy charlatans?

Epistemology is like "painting" in that it is made up of certain conceptual structures that are consistent over time. What we believe and how we know - knowledge - resembles "content" and is subject to change. Most people don't notice the former, and even Foucault, who, like a blind squirrel occasionally found a nut, wasn't wrong to point out that epistemology is a set of collective, baseline norms generally taken for granted (nor is he the first, but Foucault's gonna Foucault...). Accepted facts can change quickly, but the deeper assumptions governing their organization and interpretation move much more slowly. Truly elevating the status of the artist meant raising the visual arts from the epistemological level of craft to art, but these levels were still understood as having their old significance. Therefore, painting, sculpture, and architecture had to be placed on the same sort of unchanging, objective theoretical basis as the traditional seven Liberal Arts. But these are objectively, empirically different things, and to pretend that distinctions of good/bad are interchangable with correct/incorrect is the sort of slippery intellectual dishonesty typical of Postmodernists.

Postmodern globalists have to claim that words and categories have no meaning. They wouldn't be able to lie about them if they didn't.

The underlying theory that Alberti proposed for the art of architecture was based on the notion of concinnitas, "harmony and concord of all the parts, achieved in such a manner that nothing could be added, taken away, or altered except for the worse". This definition recognizes the importance of artistic judgment, but rooted that judgment in simple mathematical principles. Harmony meant reflecting the basic laws of the universe or "nature" to a humanist, that this was conceived in terms of number and proportion, which were based on God's greatest creation: Man.

Ghiberti, Adam and Eve, from the Gates of Parardise, 1425–52, gilt bronze, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

The creation of Adam "in God's image" was a point of contact between Renaissance humanism and Christian metaphysics. The humanists promoted the Neoplatonic idea of man as the microcosm, meaning that the basic principles that governed creation were present, on a minute scale, in the ideal human form. From a Christian perspective, God is immaterial, so his "image" implies a material accommodation or metaphor for something that is beyond direct material representation. In other words, a microcosm.

Architecturally, the microcosm provides measurable physical characteristics for abstract concepts. If the human body is the material expression of ultimate reality, it offers an objective foundation for ideal theoretical design ratios.

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Church Plan, from the Trattato di architettura civile e militare, after 1482, codice Magliabecchiano n.141, fol. 42v., Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence

Martini's (1439-1501) treatise attempted to bridge the gap between the pure theory of Alberti and actual practice. Here we see a plan based on simple modular geometries and the microcosm of the human body, but still following the basic basilica outline. If you are strongly interested in architectural theory, click for a through analysis of di Giorgio and his break from the "pure" theory of Alberti.

Claiming something you just made up actually comes before organic tradition is a typical maneuver used by Modernists, Postmodernists, and the globalist left in general. The basilica was the preeminent Western church plan since the time of Constantine, while humanist architecture was invented by Renaissance humanists. But by claiming theoretical primacy (secular transcendence), the treatise reduces the ancient form to an imperfect expression of an imaginary higher truth. Sound familiar?

Of course all people differ in their precise measurements, meaning that a humanist architecture had to arrive at a set of ideal "human" proportions. The notion of objectively ideal proportions had existed since antiquity and came to Alberti and the humanists through Vitruvius and other sources. While the idea of man as the microcosm is generally Neoplatonic, the numerical symbolism originated in the thought of the ancient followers of the philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras.

J. Augustus Knapp, Pythagoras, circa 1926

Pythagoras is a shadowy figure historically, and virtually nothing of his original thought survives. However, his influence through Plato and the later Pythagoreans is considerable, and Pythagorean numerical cosmology is the basis of Renaissance harmony and proportion. This mystical aspect of Pythagorean thought has appealed to occultist ever since.

For our purposes, the question of what percentage of these ideas actually date back to Pythagoras is much less important than what was ascribed to him in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.The Band will use the name "Pythagoras" as a catch-all term to for the complete body of thought associated with him or the later Pythagoreans.

Pythagoras was credited with discovering musical harmony and inventing the harmonic scale. Stringed instruments were common in ancient Greece, and he purportedly determined the notes of the scale by comparing strings of different lengths. He found that differences corresponding to simple fractional ratios created a harmonious progression, with the effect of halving the length equaling one octave.

Robert Fludd, De Musica Mundana, published in Utriusque Cosmi Maioris scilicet et Minoris Metaphysica, Physica Atqve Technica Historia, Frankfurt, Johan-Theodori de Bry, 1617, p. 90

The Pythagoreans, like other pre-Moderns, believed that the universe consisted of perpetually moving, concentric crystalline spheres that corresponded with the celestial bodies. This structure was geometrically flawless, and Pythagoras claimed that the spaces between the spheres were proportioned according to the ratios of his harmonic scale. The perpetual, perfectly calibrated movement created a "music" or harmony beyond human perception, but something Pythagorean mystics claimed to "hear" supernaturally, like the aural version of a vision.

This picture shows a late English Neoplatonist's take on the harmony of the spheres. It is a good image because it actually shows the hand of God tuning the cosmic scale. This idea was believed to have originated with Pythagoras.

What is so significant about this idea is the expression of music in physical, spatial terms. The same mathematical ratios behind the ethereal mystery of musical harmony and the basic structure of the universe could be expressed in in architectural relationships, thereby "tuning" the building to the music of the spheres. Like magic, architecture now has an objective mathematical theoretical basis worthy of a Liberal Art. The last thing to do was to link these ideal abstract ratios to the humanist's beloved microcosm.

Leonardo's Vitruvian Man flanked by two variations from Cesare Cesariano's Italian translation of Vitruvius' De Architectura libri Dece, Como, Gottardo de Ponte, 1521

The Vitruvian Man links the abstract ratios to the humanist microcosm. Ideal human proportions were defined as corresponding to the simplest geometric ones, as expressed in the circle and square. And just like that, we have a humanist theory to differentiate learned architectural principles from the craft traditions of vernacular builders.

The epistemological bait and switch occurs when intellectual authorities insist that the speculative absurdity of humanist cosmology is the same thing as the real objectivity of the mathematical arts - the Pythagorean Theorem still works. A purely subjective aesthetic decision - a preference for simple geometric wall architecture with Classical ornament - is portrayed as an expression of objective truth.

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, 1928-31, Poissy

Let's pause for a moment to reflect. Geometric simplicity as an architectural rule is based on the hybrid Neoplatonic, Pythagorean, Aristotelian, and Ptolemaic cosmology cooked up by Renaissance humanists.

Think about the credibility of that set of beliefs from our perspective. Now, how stupid, ignorant, and/or malevolent were Modernist theorists?

High Renaissance Globalism

The previous post introduced the weird syncretism in the humanist courts of Alexander IV and Julius II, but the intersection of these ideas with Florentine architectural theory had enormous consequences for the culture of the West. In the Christian humanist dream of Julius, all of antiquity - pagan and Hebrew alike - foretold the fulfillment of history and establishment of a new Golden Age in the coming of Christ. This idea contained a number of ingredients and could only have come late in the Renaissance, when the new intellectual authority of antiquity was solidly established. Prisca theologia, the Garden of Eden, the Roman Golden Age, Neoplatonic hierarchies, Biblical typology, and other sources tangle together in a loosely Christian version of a new spiritual empire centered in Rome. The architect tasked with realizing this in built form was Donato Bramante who had already established himself in the Rome of Alexander VI with perhaps the signature monument of Renaissance architecture:

Bramante, Tempietto, 1502, S. Pietro in Montorio, Rome.

The Tempietto was the first Renaissance design to accurately recreate an ancient building type with the correct use of a classical order. The perfectly circular Doric temple form recalls an antique martyrium, or shrine to a martyr. Round buildings were ideal for this purpose since their shape highlights anything placed at the center.

Bramante designed the Tempietto for this traditional purpose, as a marker for the site Roman humanists mistakenly thought was the site of St. Peter's crucifixion.

Bramante's Christian humanism is evident in the correct use of Doric triglyphs and metopes, only with Christian symbols rather than pagan ones.

The cross-section shows that the interior has two levels: a main story and a crypt below. The photos show the hole in the floor of the main level and the crypt. The hole in the center of the crypt was said to have been the site where the cross Peter was crucified on was placed.

The statue of St. Peter over the altar honors the saint in a way that resembles a pagan cult statue. The Tempietto really is a Christian humanist temple.

The dome reveals the geometric simplicity and perfection.

The Tempietto is more than an historically sensitive attempt at a Christian humanist shrine; it captures the strange syncretism that defined the papal culture of the High Renaissance. The shrine was located on top of a hill called the Janiculum, which was named for its association with the cult of the ancient Etruscan god Janus. This two-faced god of doorways and new beginnings had been adopted into the Roman pantheon, and credited with being the first to introduce civilization and religion to Italy. The city that he first founded was believed to be on top of the Janiculum, though there is no historical evidence to support this.

Janus-Prow, Aes Grave, circa 225-217 BC

The Aes Grave was a heavy was a heavy bronze (literal translation) Roman coin. This one shows the two-headed Janus and a the prow of a ship commemorating victory over Carthage.

The Janus myth got new life under the Spanish pope Alexander VI, when humanists in his court spun a fantastical history linking Etruscan legend with the Old Testament. According to the forger and papal confidant Annius of Viterbo, Janus was actually Noah, who settled on the banks of the Tiber after the Flood, and brought an enlightened Golden Age that was misremembered over time. The notion of a shadowy historical Noah-Janus that tied pagan and Jewish sources was typical of the syncretic "religion" of the High Renaissance. All that was missing was a connection between this magical origin and papal rule to set the stage for a new Christian humanist Golden Age.

Follower of Gérard de Lairesse, The Emperor Augustus Closing the Doors of the Temple of Janus, oil on canvas, 84.6 x 126.6 cm, Private Collection

The temple of Janus in the Roman Forum reflected the god's Golden Age association. According to legend, the doors to the temple of Janus were closed during peacetime and opened during times of war.

Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter, c. 1481-82, fresco, 330 cm × 550 cm, Sistine Chapel, Vatican

The link came in the form of keys, the symbol of Janus as god of doorways and St. Peter and the popes who hold the gates to the kingdoms of heaven. This scene symbolized Christ singling out Peter to continue his authority as the first pope.

In one of those too good to be true historical coincidences that humanists used to "prove" their visions, Annius and his followers claimed that Peter, the Christian key-bearer and patriarch, had been crucified on the exact place where Janus-Noah, the syncretic fusion of pagan key-bearer and Old Testament patriarch, had founded his city. It was this spot that was marked by the Tempietto with a perfect architectural Christian-humanist hybrid that fit this magical thinking. When Pope Julius II was elected in late 1503, he tapped Bramante for the most ambitious and controversial symbol of his proposed Christian humanist Golden Age: the replacement of the fourth-century papal basilica of St. Peter's with a gigantic centrally-planned, classically-inspired temple. Although vastly larger than the Tempietto, St. Peter's also marked an important site in the life of Peter: his burial place, directly beneath the center of the dome.

Bramante's plan for St. Peter's with an artist's recreation

Old St. Peter's, completed circa 360, demolished early 16th century, Rome

Bramante's humanist harmonies are apparent in the plan. The proposed building, with its prominent dome, looked nothing like the Early Christian basilica.

New St. Peter's took over a century to complete, and the basilica shape was restored by the addition of a nave in the early seventeenth century, but it is the decision to demolish Constantine's original that is important for our purposes. The symbolism of replacing such a venerable monument of Christian history with a new, culturally alien form of "perfection" should ring familiar.

St. Peter's from the rear, where the nave is less visible and Michlangelo's original design clearer, and Michelangelo's simplified plan. The simple proportions are even clearer than in Bramante's version.

Michelangelo's presentation model of the dome, and the actual dome as completed by Giacomo della Porta.

Bramante didn't get too far before his death in 1514, and after several unproductive decades, it was Michelangelo who simplified the plan and designed the massive dome between 1546-64, although that wasn't finished until 1590 by his student, Giacomo Della Porta.

It is not surprising that Michelangelo designed like the sculptor he was, and his St. Peter's works best from a distance, like the abstract sculptural appearance of Modern design. His exterior is punctuated by huge rhythmic Corinthian pilasters and tied together with a massive entablature, creating a sense of unity as well as incredible tension. This tension is resolved by the continuance of the pilasters into the columns and ribs of the dome. As a work of art, Michelangelo's design is a success, but it has no connection with the traditions of the Church.

Both the Tempietto and St. Peter's are pivotal incidents in the transformation of architecture from a taste-based practice to a theoretical art. Here, the theoretical purity of Vitruvian geometry joins with syncretic humanist antiquarianism to express the dream of a new Golden Age that would be Christian, but enlightened by the newly rediscovered wisdom of pagan antiquity. Harmoniously proportioned works of classical architecture aligned with the the basic structure of the universe to provide the ideal venue for this utopian dream of human perfection.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Villa Tugendhat, 1928-30, Brno, Czech Republic

That the dream proved as hollow as the architectural metaphysics is the point, because it is essentially the same dream that enabled the Modernists and their offspring to take over architecture in the twentieth century.

Architecture was established as an "art" with objective first principles, which is an objectively false characterization. The entire "discourse" was founded on a good/bad correct/incorrect bait and switch, which means all its subsequent conclusions are based on nothing more than the desires of those holding them. Rhetorically, this is fantastic, because the theorists have managed to pass subjective opinion off as empirical fact. Dialectically, the entire theoretical edifice is built on sand. Coming back to the question of authority, whoever controls the theory controls the "truth". In Renaissance Rome, rational proportions and classical vocabulary were de rigueur because the syncretic humanists were calling the shots. In Modernity, lumps of metal and concrete were in vogue because sociopathic anti-humanists were in charge. But the division of vernacular building from theory-based architecture is a constant.

Cola di Caprarola and others, Santa Maria della Consolazione, 1508-1607, Todi

Geometric theoretical Renaissance architecture in the manner of Bramante.

The next post will consider how these localized Renaissance ideas came to take over European then much of world architecture in the following centuries, because this one needs to wrap up. It was important to spend the necessary time to pinpoint what happens to architecture and the culture around it. New authorities and the humanistic belief in human perfectibility combine to recast the fine arts as Liberal Arts and transform architects into theoreticians. What was needed was for the idea of individual artists as authorities to become universal in the West.

Models of Authority

Two models of architectural authority emerge from the Renaissance that continue to shape attitudes towards the field today. These are most easily introduced by their archetypes, two sixteenth-century designers who rank among the most famous of all time: Michelangelo (1475-1564) and Palladio (1508-1580).

Daniele da Volterra, Michelangelo, circa 1544, oil on panel, 88.3 × 64.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Alessandro Maganza, Andrea Palladio (detail), oil on canvas, Private collection, Moscow

The former was heralded as a universal artist, master of sculpture, painting, architecture, and an accomplished poet, who developed a fiercely personal artistic style that often defied contemporary fashion. The latter was a theoretically-minded architect who moved in Venetian humanist circles and provided illustrations for a translation of Vitruvius (the text of Vitruvius survived, but his original illustrations were lost) before writing his own immensely influential treatise. These two models - the inspired, independent genius, and the aesthetic theoretician - still represent different impulses in architecture today.

Michelangelo

As we saw with St. Peter's, Michelangelo thought of architecture like a sculptor, designing bold and original compositions that neglected the "rules" to create interest and dynamic tension.

Michelangelo, Laurentian Library, beg. 1525, Florence

The entryway for the Laurentian Library that he designed for the Medici in Florence follows Brunelleschi's basic template of classically articulated wall architecture in a traditional cool color scheme, but arranges them in completely new ways.

The Classical elements have no resemblance to any past usage

Volutes never hang under columns.

The pilasters and columns are recessed, which inverts their normal role as protruding or freestanding verticals.

The staircase has no antique precedent and resembles a waterfall more than a pure Classical form.

The wall opposite the stairs inverts the usual arrangement of ornament, with niches on the outside but blank space in the center. Usually the decoration is centered to draw the viewer down the staircase.

The crowding of the decorative elements creates pressure and tension that are unclassical in spirit.

As a whole, the design uses the sort of Classical elements that would have appeared on the exterior of a building rather than the interior. And they did know the difference.

Raphael, The Loggetta of Cardinal Bibbiena, 1516-17, fresco, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican

The recent discovery of the Golden House of Nero had given artists a sense of what ancient interiors had looked like, and this led to designs "all'antica" like those produced by Raphael and his workshop. Michelangelo opted to mess with viewers perceptions and use familiar exterior elements in odd ways on the inside.

Michelangelo didn't write treatises like Alberti or Palladio, but did require viewers that understood the basic rules of Classical architecture in order to appreciate the way he breaks with convention and confounds expectations. Recessed columns and empty niches are only significant if you understand what these things are supposed to look like. To understand how one makes a career of rule breaking in the humanistic aesthetic culture of the Renaissance, we have to remember that at the same time that art theory was coalescing, artists were being elevated to the status of geniuses. No one fit that description like Michelangelo, whose prickly personality and incomprehensible talent fed a reputation for divinely-inspired talent. This allowed him to break rules on the authority of his own genius, and while this was accepted by his patrons, it made him a poor model to develop into a systematic approach.

Federico Zuccari, Palazzo Zuccari, begun 1590, Rome

The notion that artists were free to experiment was the basis of the sixteenth-century movement known as Mannerism. Architects followed Michelangelo's example in violating rules in search of creative novelty. This house is fanciful, but it isn't following any rule other than Zuccari's imagination.

Palladio

Andrea Palladio had a very different attitude towards architecture, and was typical of Venetian theorists for treating it as a separate field, and not one of the three arts of design as Michelangelo did. The influence of Vitruvius on his architecture was considerable - he illustrated translations of Virtuvius' Ten Books, but his influence comes from his own unfinished treatise.

Palladio, I quattro libri dell' architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), Venice: Domenico de' Franceschi, 1570. Click here for a quality scan of the 1581 edition.

Palladio's treatise included detailed drawings of antique monuments as well as newer buildings. These pages from Book One show a Corinthian capital, entablature, and ornament.

On a theoretical level, he recalled the architects of the early Renaissance by deriving simple, harmonious geometric principles from his study of ancient architecture and understanding of Pythagorean ratios (click here for a thorough discussion of Palladio's relationship to his Renaissance predecessors).

Palladio, Villa Capra (Villa Rotonda), 1567-71, outside Vicenza, Italy

Palladio's most famous building combines the simple geometries of circle and square while keeping ornament to a minimum.

The geometric harmony is apparent in the section, plan, and massing.

The pedimented portico recalls the Pantheon, but the villa is symmetrical on all sides.

The abstract perfection is apparent from a distance. This is a forerunner of the environmentally insensitive "sculpture" of Modernist architects.

Rather than unbrideled creativity, Palladio stood for a measured theoretical approach based on careful study and easily taught as a curriculum.

Vicenzo Scamozzi, Villa Pisani (La Rocca), 1574, Bagnolo di Lonigo

The Earl of Burlington, Chiswick House, 1726-29, London

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello, remodeling begun 1794, near Charlottesville, VA

Contemporary Palladian design in New York

The creative genius and model theoretician were two archetypes of architectural creativity that emerged from the Renaissance transformation of the Western arts. The likes of Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius were still playing these roles. What remains to be seen is how this wacky humanist faith in syncretic Christianity and secular transcendence became the backbone of architecture in the West.

Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, Wallace Harrison, United Nations Secretariat Building, 1948-52, New York

No comments:

Post a Comment