If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right.

Dan Marin and Zeno Bogdanescu, Union of Romanian Architects Building, 19th century house, remodeled 2003-2007, Bucharest

Presented without further comment.

For this to have happened, there had to have been a break in the organic social, cultural, and religious unity that we saw expressed in the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages. A transformation of this magnitude requires a change in the bedrock assumptions about cultural authority and meaning. How could architecture move from the Medieval master mason, a refined craftsman who competed on the basis of skill and popularity, to the widely-reviled provocations of intellectually-challenged agoraphobes posturing as oracles? By detaching "intellectual" and "artistic" pursuits from, and setting them against, the societies they emerged from.

The North Transept rose window in Chartres Cathedral, circa 1235.

Lets return to the windows of Chartres Cathedral, which, as we saw in the last post, was something of an organic expression of unified communal values. Chartres is famous for the quality of its glass, and the three huge early 13th century rose windows are high points of High Gothic design (click here for a nice summary of this window).

Coronation of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile at Reims in 1223, from the Grandes Chroniques de France, circa 1455-1460 Paris, BnF, MS. Français 6465, f. 247

Blanche of Castile and Louis IX, detail from the dedication page of the Bible moralisée de Tolède (Bible of Saint-Louis), circa 1220-1230, illumination on parchment, 34.4 x 26 cm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

The window was paid for by Blanche of Castile (1188-1252), a Spanish princess and Queen of France with her husband King Louis VIII from 1223 to his unexpected death in 1226. Mother of the the pious King St. Louis IX, she ruled as regent during her son's minority and while he was on Crusade.

A skilled administrator, politician, and patron of the arts, Blanche and was an important figure in the shaping of Gothic Europe, both in her own right and through her influence on her son.

The royal patronage was made clear in the heraldic lancets, where the alternating arms of the French monarchy and Castile denote Blanche's identity.

Acts of the Apostles window, 1215-25, Chartres Cathedral

If we recall, the windows at Chartres were funded by members of the community (craft guilds, merchants, clergy, local aristocrats, etc.), and these also represented their sponsors. The Lives of the Apostles window in the middle of the central chapel in the apse was sponsored by the Baker's Guild, and has recently been beautifully restored. The three large panels showing the making and shaping of dough and selling loaves are at the bottom of the actual window, where they are most visible.

So the cathedral represented a universal vision of the coalescing French nation where both the bakers and the monarch had a place.

The Queen's rose is obviously larger and more spectacular - having a place in a community doesn't rule out social hierarchy - but the overall quality and style of the art is the same.

Central panel of the north rose and the Ascension at the top of the Apostles window. You can really see the difference the restoration made, since the rose hasn't been done yet.

This is the "cathedral unity" in Medieval architecture that was introduced in the last post, and serves as an excellent historical example of an architecture that developed organically alongside the beliefs and values of a distinct culture.

Pioneering art historian Erwin Panofsky published an interesting piece in 1951 likening the complexity and unity of cathedral architecture to the philosophical syntheses of the contemporary Scholastics as expressions of a larger cultural impulse towards unity. It is more of an intellectual performance than grounded history, but it is much better than most recent art writing and is worth a read if these things interest you.

The architects who designed and oversaw the construction of the cathedrals were master masons who learned the techniques through years of work under other masters. In this way skills were passed down and refined without being held to an external objective standard like the Greek orders. There are consistencies, but they are not rigid in a theoretical way.

Life of St Cheron Window, early 13th century, Chartres Cathedral

And the masons were part of the community that built the cathedral. This window was donated by the mason's guild, with identifying panels at bottom depicting dressing stones and carving statues. It needs to be reiterated that the cathedral unity was not some sort of socialism. Medieval society was rigidly hierarchical, and the master mason who could build Chartres was very well compensated. But the hierarchy fit within a unified Christian cultural vision that placed everything in this world on on the bottom rung of the metaphysical ladder. From God's perspective, there is no meaningful difference between Blanche of Castile or the bakers and sculptors in the overall scheme of things.

This detour into the Middle Ages was necessary to show the unity that existed between architecture, faith, community, and culture on the eve of the Renaissance, because, to repeat the opening of this post, this is what had to be shattered to start the road to the debasement of Modernism. This is a very important point, and prefigures the "Roots of Globalism" gig that the Band is currently rehearsing. Consider the following change in cultural authority through the lens of contemporary attacks on the Western nations and their traditions associated with "progressives" and their globalist puppeteers.

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, Contrasts : or a parallel between the noble edifices of the middle ages, and corresponding buildings of the present day; shewing the present decay of taste. Edinburgh: J. Grant, 1891

This is the unity of architecture and community that reforming Gothic Revialists like Pugin held up against the "rational" predations of early Industrial Revolution Modernism. His book Contrasts makes a number of comparisons between human, organic, communal structures and the disruption and social trauma of newly urbanizing England.

In order to create a rupture in this sort of cultural unity, it is necessary for a competing perspective to emerge. In contemporary terms, we are familiar with externally and internally driven forms of this process. Diluting and displacing a native population under the false fronts of "immigration" and "diversity" are acts of invasion by external entities, though this is complicated by the collusion by quislings within the nation. Then there is the internally-driven process of reframing norms and mores, generally involving the ridicule of the traditional culture as stale, parochial, or outdated.

Saturday Night Live's "Church Lady" is exactly the sort of grotesque parody that the left has used to undermine American culture for decades. It involves the creation of "cool" countercultures that can then be used to cast the organic ethos of a nation as backwards and repressive. This has gone on for a long time; Modernists, anarchists, Marxists, bohemians, beats, hippies, punks, and progressives have all been branded as some form of cool by leftist cultural organs .

It's a short rhetorical slide from dinosaur to stupid to evil, as nationalists are well aware.

The Band encourages looking into who does the promoting.

The transformation of architecture was a consequence of perhaps the most significant cultural reframing since Classical Greece: the emergence of humanism in the Italian Renaissance. When thinking about parallels between the Renaissance and Modernism, it is important to keep in mind that history does not actually "repeat" itself, it echoes. This means that often times, the people blathering on about "the lessons of history" are completely blind to the same processes unfolding beneath their noses. Think of all the hysterics melting down over the "next Hitler" while remaining unaware that Hitler was the "next" Napoleon, a strongman emerging from the chaos of a failed "progressive" regime. The repetition is structural, not exact; and the superficialities that people pay the most attention to are what differ the most.

Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, 1477-1482, 203 x 314 cm, Uffizi, Florence

This painting was a gift for a Medici wedding and uses figures from mythology depict the coming of spring as wish for a happy marriage. The use of pagan figures from antiquity is a sign of the popularity for this humanistic frame of reference.

Renaissance humanism was an intellectual insurgency launched from outside established educational institutions that created an alternative set of cultural authorities. It began as an apparently reasonable improvement in society before evolving into a completely antithetical world view; one that offered the promise of transcendent knowledge through purely human effort. That fact that this is impossible proved little obstacle, because humanism was a highly rhetorical movement that was not given to systematic thought. Its "authorities" are as arbitrary and unsubstantiated as the Modernists and their offspring, though their aesthetics are infinitely superior.

Why the Renaissance?

It is impossible to state why the Renaissance happened when it did, but there were conditions unique to medieval Italy that made it conducive to this change in thinking. History and geography made it enthically different from predominately Germanic/Celtic north, and brought much more contact with the Byzantine and Islamic worlds. Fragmented since the collapse of the Empire and subject to successive invasions, Italy was unique for having both the center of Western Christendom in Rome and something of an outsider's perspective on the cultural unity of the Gothic North at the same time.

During the sixth-century, the Ostrogothic kingdom was destroyed by the Byzantine reconquest before the invasion of the Germanic Lombards (Longobards) divided the penninsula. By the turn of the ninth century, the Frankish Charlemagne had brought most of Italy into his vast empire, but there were few Frankish settlers.

The turbulent eleventh century.

Maps of Italy in 1000 and in 1084. During this period, the Muslim invaders in Sicily were conquered by the Normans and the lingering Byzantine presence in the south came to an end leaving a cluster of small territories.

Italy in 1300 and 1494. The fragmentation reaches an extreme around 1300 before some consolidation occurs.

So we are left with a microcosm of Europe: a cluster of distinct "nations" that also share a larger cultural framework that distinguishes them somewhat from the rest of Western Christendom.

A related factor is the relative proximity to the physical remains of Roman antiquity. Simply by inhabiting the Roman heartland, medieval Italians had a familiarity with Roman cultural forms that was not available in Northern Europe, and so could be influenced directly rather than through second-hand transmissions.

Italy in 1300 and 1494. The fragmentation reaches an extreme around 1300 before some consolidation occurs.

So we are left with a microcosm of Europe: a cluster of distinct "nations" that also share a larger cultural framework that distinguishes them somewhat from the rest of Western Christendom.

A related factor is the relative proximity to the physical remains of Roman antiquity. Simply by inhabiting the Roman heartland, medieval Italians had a familiarity with Roman cultural forms that was not available in Northern Europe, and so could be influenced directly rather than through second-hand transmissions.

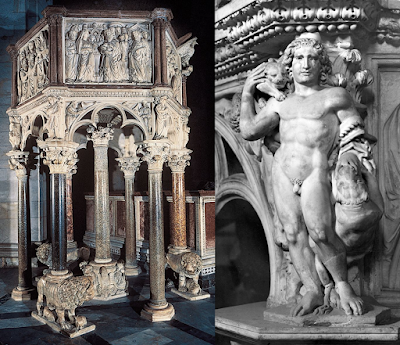

Nicola Pisano, Pulpit, 1260, marble, 465 cm high Baptistry, Pisa

An example of classical influence: Nicola's pulpit is Romanesque in the squat proportions of the figures, but this personification of Fortitude stands out for its accurate musculature and contrapposto stance; two features of ancient Roman art.

Sarcophagus with scenes from the Myth of Phaedra and Hippolytus, circa 180 AD, marble, Louvre, Paris.

Nicola wasn't a classical revivalist in a theoretical sense, but did have access to ancient works like this sarcophagus, which was in his native Pisa in the thirteenth century. A fine work of Imperial sculpture along Hellenistic Greek lines, it included multiple anatomically correct figures in variations of contrapposto. The one on the left in the lower detail could actually have been Nicola's model.

In addition to their small scale and distinct histories, the city-states of central Italy also became extremely wealthy. They developed advanced economies around textiles and trade, and essentially created modern banking, which brought prosperity far beyond what size and natural resources would predict.

Master of the Cocharelli Codex, Avarice, from Latin prose treatise on the Seven Vices, c. 1330-1340, British Library, Add. 27695 f.8r

Modern banking began when Tuscan grain merchants teamed up with newly arrived Jewish moneylenders to maneuver around the Abrahamic religions' prohibition on lending at interest. This simple formula was refined by the famous Medici family.

The Wedding at Cana and The Expulsion of the Moneylenders from the Temple, Psalter, first quarter of 13th century, British Library, MS Arundel 157, f. 6v.

A contrast between proper Christian fellowship and sinful usury. The emergence of commercial banking in late Medieval Italy was accompanied by frequent expulsions of foreign moneylenders.

The justification was an interpretation of a verse from Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Torah as well as an Old Testament book of the Bible.

"

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Moses on Mount Sinai, 1895, 73.5 x 114 cm, oil on canvas Private collection

The interpretation hinges on the notion of stranger. As always, the Bible can be interpreted in many self-interested ways when passages are taken in isolation.

A contrast between proper Christian fellowship and sinful usury. The emergence of commercial banking in late Medieval Italy was accompanied by frequent expulsions of foreign moneylenders.

The justification was an interpretation of a verse from Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Torah as well as an Old Testament book of the Bible.

"

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Moses on Mount Sinai, 1895, 73.5 x 114 cm, oil on canvas Private collection

The interpretation hinges on the notion of stranger. As always, the Bible can be interpreted in many self-interested ways when passages are taken in isolation.

Small, economically advanced states required large numbers of clerks, diplomats, and administrators resulting in much higher literacy than in the rest of Europe, and the legalistic nature of this society brought greater awareness of Roman law.

Opera aliqua de re iuridica, 1276-1325, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Borgh. 265, f. 1r.

The opening page from a legal manuscript from the Vatican Library from the late thirteenth century. The Curia (the administration of the Chuch) employed an large number of scribes who were skilled in Latin. When the papacy returned from Avignon, this provided employment for numerous humanists and began the shift of the "center" of the Renaissance from Florence to Rome.

The Vatican Curia was the largest collection of Latinists, but each state would have its own, resulting in an extensive culture of literacy.

Then the papacy left Rome altogether, moving to Avignon in the south of France after a series of political machinations by the French king Philip IV. Philip, who also destroyed the Templars with similar tactics, orchestrated the election of the French Pope Clement V in 1309, who then moved the Curia to Avignon for "security" reasons. The Avignon Papacy ended in 1376, but the Church split three years later, and the Schism wasn't ended until 1417, with the election of Martin V.

Pierre Poisson & Jean de Louvres, Palais des Papes, beg. 1252, comp. 1352, Avignon, France

The largest Gothic palace ever built housed the papacy during the Avignon period, or, to use the popular Old Testament allegory at the time, the Babylonian Captivity, and the French anti-popes of the Schism. The Avignon court became an international crossroads, and it is there that artists from around Europe devised an international art movement called the International Gothic. Northern styles never had this influence in Rome, where the Classical and Early Christian legacies are too strong.

Allegorical Map of Rome with a personification of the city as a widow, mourning the loss of the Papacy, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS Ital. 81, folio 18

The Avignon Papacy was devastating to Rome, but freed the rest of Italy from the twin threats of increasingly imperialistic popes and interventions by the larger European powers seeking to influence the Church. This created the space for local cultures to flourish in the small states of central Italy like Florence and Siena.

The result of these unique conditions was a cluster small, militarily weak, wealthy states that share cultural and linguistic frameworks, but were locked in fierce competition. There is war and consolidation throughout the Renaissance, but cultural production - art, poetry, scholarship, and architecture - also becomes an important battleground, spurring a climate of innovation and one-upmanship.

Allegorical Map of Rome with a personification of the city as a widow, mourning the loss of the Papacy, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS Ital. 81, folio 18

The Avignon Papacy was devastating to Rome, but freed the rest of Italy from the twin threats of increasingly imperialistic popes and interventions by the larger European powers seeking to influence the Church. This created the space for local cultures to flourish in the small states of central Italy like Florence and Siena.

The result of these unique conditions was a cluster small, militarily weak, wealthy states that share cultural and linguistic frameworks, but were locked in fierce competition. There is war and consolidation throughout the Renaissance, but cultural production - art, poetry, scholarship, and architecture - also becomes an important battleground, spurring a climate of innovation and one-upmanship.

Duccio, Maestà (Madonna with Angels and Saints), 1308-11, tempera on wood, 214 x 412 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena

The wealth of the Italian states spurred an artistic arms race, with artists like the Florentine Giotto and the Sienese Duccio as national champions. Duccio's masterpiece, shown here in restored form, was intended for Siena's new cathedral, itself a monument of communal pride and identity.

These are by no means the only features that made late medieval Italy unique, but they central ones, and they raise important points. We can already see the formation of the distinct national identities that define the West and their interaction with the larger structure of Christendom in everything from itinerant bankers to patriotic popes, to emerging artistic identities. The Renaissance, therefore is best understood as an Italian movement within a larger European framework, and when it spreads to the rest of Europe, it takes different forms in different places. Historical surveys focus on the big patterns, and tend to present the Renaissance as a pan-European movement that begins the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times, but this is only accurate in the largest sense. The Renaissance began in a very narrow Tuscan context, which means that although its downstream consequences were enormous, is basic structure - its assumptions and positions - were formed in reaction to a very specific historical circumstances.

In short, a late medieval Italian academic

dispute was the foundation for every

subsequent European fantasy of a

universal, trans-national ideal.

Reframing an organic culture requires the introduction of competing perspectives, and the Renaissance match was lit by Francesco Petrarcha, or Petrarch (1304-74), as much as anyone. It is necessary when dealing with broad subjects in small posts to use representative figures as examples of important themes, but Petrarch basically invents a new concept of history, and in so doing, opens a new perspective on European culture. The medieval notion of human history as a chain of metaphysically empty events next to the cosmic history of the Bible and the personal quest for salvation was explained in a previous post. But Petrarch flips this by ascribing relative value to purely human accomplishments according to an new objective, yet worldly, standard.

Justus van Gent, Francesco Petrarca, circa 1472-76, oil on panel, 112 x 58 cm, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

Petrarch (1304-74) is often considered the first Renaissance humanist, and was certainly an inspiration to the following generations like Bruni. He introduced the idea that history of historical decline when he judged the cultural achievements of classical antiquity to be superior to his own times. The Renaissance that followed began as an attempt to remedy this loss. Note the familiar laurel crown signifying triumph and immortality in Classical terms.

Thinking of history in terms of loss and rebirth introduced the notion that periods can be characterized and compared on secular grounds. The use of the term Dark Ages in reference to Medieval Europe was a Renaissance invention, since the Classical heritage had to be lost in order to be recovered. The fact that this completely misrepresented medieval culture is irrelevant, and the strength of the peak - decline - rebirth model is apparent in the fact that we still refer to "the Middle Ages" today.

Petrarch's "Letters to Posterity" address ancient pagan figures in familiar terms, decrying the cultural decay that claims has occurred since antiquity. The rhetorical flavor of Reniassance humanism is already apparent in his flowery and dramatic prose style, as is his intensity.

The humanist movement began outside of the educational institutions of Medieval Europe among private intellectuals who supported their activities by writing, teaching Latin, and/or working in the administrations of Italy. Their rhetorical skill and unshakable faith in the supremacy of ancient culture made them compelling in the way that "edgy" radicals often are, and they found support among the fashion-conscious elites of Italian society.

Arnolfo di Cambio, Palazzo Vecchio, 1299-1313, Florence

Florence was a republic, which distinguished it from most of Europe, and the early humanists drew on Republican Roman literature to foster a sense of civic pride and identity. Cicero was a favorite, providing a model of Republican virtue and flawless Latin style. The Signoria, or governing council met here.

Pedro Berruguete, Portrait of Federico da Montefeltro with His Son Guidobaldo, circa 1474, tempera on canvas, 134 x 77 cm, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino

Federigo was a model Renaissance prince (technically a duke): a mercenary commander who used his wealth to create a humanist paradise in Urbino. This portrait shows him to be a scholar-warrior, while his son, dressed as a Byzantine emperor, shows his dynastic hopes.

Humanists brought value to Renaissance courts, where the small scale meant an expanded role for female aristocrats with the household. When circles of trust are that narrow and the constant scheming and machinations endless, educated daughters and wives were valuable assets. Universities and cathedral schools were not open to women, but private tutors could teach the necessary lessons in statecraft, rhetoric, and virtue.

Supported by the courts and their own enterprises, the humanists were able to attack the traditions and epistemological foundations of the cathedral unity observed earlier. It is important to remember that these were canny thinkers, unlike the Postmodern simpletons of more recent times who require censorship and control, and understood that this required an attractive alternative discourse. The outcome is an entirely new epistemology that changes the nature of Western thought.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, St. John the Baptist, 1412-16, Orsanmichele, Florence

Donatello, St. Mark, 1411-13, Orsanmichele, Florence

These were two very high-profile statues produced in Florence by leading Renaissance pioneers for the same project at the same time. The older Ghiberti sculpted in the aristocratic style of the International Gothic, with sweeping, graceful curve and a stylized S-shaped pose. Donatello's figure had a unprecedentedly lifelike expression and a body inspired by ancient sculpture. Note the contrapposto pose beneath robes that fall naturally to show the form underneath. The coexistence of such different styles is indicative of the cultural shift brought about by humanism.

Looking at the rupture of the cultural unity of the Middle Ages, we get an insight into the Postmodern notion of discourse as a set of beliefs or assumptions masquerading as reality. We know that our representations and customs aren't "objective" reality in a metaphysical sense because the human experience of the world is an encounter between a limited, individual subjectivity and a virtually infinite external environment. But when a culture develops organically among a group of people over time, it is an adaptation of their inherent traits to their specific social and geographical environment. The culture feels like a natural fit, since there are no inherent conflicts between the people and the world view. Individuals may be alienated for any number of personal reasons, but cultural norms and expectations are accepted unself-consciously. It is true that specific cultural forms are always arbitrary, but the long process of historical development creates a harmonious fit between a nation and its people.

Discourse presumes that the ontological difference between cultural expression and ultimate reality disqualifies the former from having any legitimate meaning. To an empiricist, this is simply human nature, and cultures are judged on their outcomes; how do they manage the gap between human subjectivity and objective reality. But to a Postmodernist, the difference is absolutely definitive, which is a much more hostile posture towards culture, or, more specifically, the culture of the West. A naturally-evolved cultural unity can only be reframed as hostile by introducing a competing point of view into the national body, and this is only possible when the practical nature of "truth" is in question.

This is who we are

becomes

which one are we?

Humanism, like Postmodernism, began as a relational concept, in that it was coalesced in opposition to specific historical circumstances, but claims "universal" applicability.

Gherardo di Giovanni del Fora, Dialectic and Rhetoric, 1470-90, for Martianus Capella, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, Vatican Library, MS. Urb. Lat 329

Renaissance humanists attacked the basis of scholastic thought by replacing logic, or dialectic, with rhetoric as the basis of epistemology. This allowed them to use philology and style as arguments, but opened door to relativism and subjectivity in truth claims. Civic humanists even promote a "rhetorical" historiography on Roman models where it is ok to distort the facts to "clarify" the larger message. But this rhetorical focus forms purely as a reaction to the dominance of dialectic in the universities. Attempting to make it universal leads to the incoherence of creating "objective" authorities (the ancients) on rhetorical grounds.

Postmodernism has challenged the academic culture of its day by reframing reason with rhetoric as well. The difference is that the humanists were more intelligent and erudite, despite their limited access to information.

Humanists characterized themselves as a new class of individuals apart from, and in opposition to, the medieval schools, where theology was the preeminent field of study. But the movement began with an awareness of decline in "secular" culture (as much as that term applies to the Middle Ages) and introduced a focus on human affairs as ends in themselves. The early humanists were Christian, but their interests were secular, and this was intertwined with notions about the cultural superiority of antiquity from the beginning. From the time of Petrarch, the the humanist interpretation of ancient world provided the standard against which contemporary times were measured. In practical terms, Classical authors could be "sold" as the key to a richer, more virtuous, and rewarding life.

Simone Martini, Petrarch's Virgil (title page), c. 1336, Ms. Sp. 10. N. 27, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Martini was one of Duccio's greatest pupils, but left Siena for the papal court in Avignon, where the culture was more in keeping with his courtly Gothic tastes. There he met and became friends with Petrarch, and painted this illuminated title page for the poet's copy of Virgil. Note the sinuous, curving Gothic forms that prefigure Ghiberti's with the Classical pagan subject matter.

Another parallel with Postmodernism is the philosophical bait-and-switch. This occurs when a movement is sold initially as an improvement on the existing order but metastasizes into an inversion and replacement of that order. In the case of humanism, this meant tearing down and supplanting the scholastic epistemology of the medieval schools. As time passes and humanism matures, we see the study of antiquity evolve from a guide to better living and style to a culture authority to rival the Christian foundations of Europe.

Authority

Zeroing in on humanist intellectual culture, the Renaissance emphasis on rhetoric makes more sense when we consider the interaction between the love of antiquity and opposition to scholastic thought. From the beginning, Petrarch lamented the inferior quality of Latin letters in his day compared to ancient Rome, and the early humanists sought to perfect their own mastery of the language by emulating ancient models. Cicero was probably the most popular of these, for his writings on rhetoric and oratory as well as for his civic virtues and Stoic philosophy. The problem for the humanists is that the role of Latin had changed since ancient times. Virgil and Cicero wrote with the natural ease of native speakers, while in the late Middle Ages, Latin was the language of the Church and serious scholarship, but was a second language after one's vernacular mother tongue. The humanists developed tremendous proficiency in Classical Latin, but did so by mastering it from outside, like a fixed code. It was a rhetorical tool, a way to demonstrate erudition through mastery of the proper forms, rather than the basis of a living community.

Gustave Doré, Dante and Virgil in the Ninth Circle of Hell, 1861, oil on canvas, 315 x 450 cm, Musée de Brou, Bourg-en-Bresse, France

No one weaponized linguistic proficiency like Lorenzo Valla (1407-1457), the smartest of the humanists, and a pioneering philologist most famous for having debunked the Donation of Constantine. But Valla is most relevant here for his use of classical Latin to attack the underpinnings of scholastic thought. Rather than engaging with the intricate logic, he pointed out areas where medieval Latin deviated from its ancient usage as evidence that the later was corrupted, and didn't actually say what the authors thought it did. We could argue that this is intellectual bad faith, in that Valla made no attempt to find arguments in this uncertain language in the way that a translator would when confronting an ambiguous passage, but it's a better option than trying to engage the likes of Aquinas on his own terms.

Cristoforo Majorana, title page to Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, Latin translation by Lorenzo Valla, 1475, Universitat de València, Biblioteca Històrica, Ms. 379, f. 3r

Valla's translation of Thucydides. He learned Greek from Byzantine emigre scholars, and became nearly as skilled in that language as the Latin he was famous for.

Since the Band formed to tackle Postmodernism, it is a good time to point out a parallel between Valla and Derrida, another whip-smart iconoclast who used linguistic indeterminacy to attack an established educational order. Both humanism and deconstruction sidestepped issues of content to claim that their opponents' language didn't really say what they thought it did, rendering the rest of their argument moot. But there are important differences as well. Derrida concluded all language was metaphysically meaningless; to him, Cicero's Latin is no more objectively meaningful a communication for the transmission of ideas than Aquinas'. Valla, on the other hand, looked to replace the flawed language with an alternative standard of perfection based in classical usage. In terms of authority, we could say that Derrida rejects the possibility of objective external standards in order to reserve all authority for himself, while Valla transfers authority from the medieval logicians to the pagan stylists of ancient Rome. History doesn't repeat, but it does echo.

Superficially, Valla's attacks seem artifacts from the dusty history of philology, but they are representative of far more profound ideas. By dismissing scholasticism on entirely new criteria, he is introducing an alternate authority into what had been the cathedral unity of medieval thought.

Vincenzo Foppa, The Young Cicero Reading, circa 1464, fresco, 101.6 x 143.7 cm, The Wallace Collection, London

Classical authors shifted from models for personal style and virtuous living to the last word on epistemology. From here, it is a short hop to "the ancients" being pedestalized as authorities on most everything, in an early version of invoking the Philosopher's Name in lieu of argument.

To sum up, we see the creation of a rupture in the unified intellectual culture of Medieval Christendom by the introduction of a new set of competing authorities that develop in opposition to the dominant discourse, but claim primacy. This takes many forms, but a focus on rhetoric over logic, and a new model of historiography are among the most important. This is critical. Consider the structure of the oppositions:

Medieval culture evolves organically over time, through the turbulent centuries following the collapse of the Western Empire and the rise of the European nations, into a shared identity that adapts to changing times without losing its roots. This is by definition not a theoretical or systematic process, but the way a people reacts and evolves to the natural pressures of an unpredictable world.The key here is "a people". Different nations and cultures have different norms and expectations that are deep rooted through generations of nature/nuture alchemy. They won't necessarily react the same way to the same circumstances, which is why different cultures develop such different ways of framing the same basic ideas.

Clockwise from top left: San Marco, beg. circa 1063, Venice; Pisa Cathedral, beg. 1063; Milan Cathedral, beg. 1386; Siena Cathedral, beg. 1215

Human biodiversity and environmental specificity ensure that when cultures are free to express their identities freely, they do not look the same. There is no universal standard to govern the structure of language and literature, the appearance of cities and buildings, the conventions of art and culture, social norms and the nature of government, etc. Change is driven internally, through culturally determined reactions to new conditions.

Leonardo Bruni, History of the Florentine People, late 14th century manuscript, University of Syndey Library.

Consider the Renaissance relationship between history and authority. The early humanists knew virtually nothing about the ancient world by the standards of modern classics, but this did not stop them from claiming that their minuscule comprehension constituted an absolute standard of socio-cultural perfection. Bruni's history is structured after Roman models, and celebrates the civic virtue of Florence in humanistic terms.

The Renaissance, for all it's dazzling artistic achievements, introduced secular transcendence into Western thought as a competing authority, in the form the bizarre obsession with "antiquity" that comes to define that period.

So from the very beginning, we have a contemporary fantasy promoted as the new awareness of the real truth, used to dismiss the natural process of organic cultural evolution as debased, barbarous, and false. Sound familiar?

Imaginary priors are intellectually dishonest but rhetorical gold if you can sell them. They give true believers a pretty picture to cling to, but since they don't exist, they can never be attained, creating perpetual "revolution" for power seekers to exploit. At least until they spiral out of control and end in violence and societal collapse.

Jacopo della Quercia, Temptation, 1425-28; The Creation of Adam, 1425-35, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, c. 1435, marble panels, 99 x 92 cm, entrance to S. Petronio, Bologna

Thomas Cole, The Course of the Empire, 1836, New York Historical Society: Consummation, oil on canvas, 129.5 x 193 cm; Destruction, 1836, oil on canvas, 100.33 x 161.29 cm; Desolation, oil on canvas, 100.3 cm x 161.2 cm

The new model of history as a collapse and progressive recovery was seemed compatible with Christianity, which was itself built on a Fall from a lost state of primordeal perfection. Obviously the Eden and Greco-Roman antiquity are very different lost states of grace, but what matters is the underlying structure. Humanity's fall from spiritual grace follows the same trajectory as its fall from cultural grace.

This is not necessarily as blasphemous as it appears when we remember the importance of allagory, typology, and analogy in Medieval thought. Humanism appeared in a culture where the notion that things represent other thing figuratively, or through a glass darkly, was common, so the idea that structural parallels could be meaningful was intuitive. What was different was the nature of the parallel. Medievals tended to see analogous connections between the physical and spiritual worlds and/or the Testaments, while the humanists turned to historical similarities between the Bible and pagan thought as ancient sources.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Meeting of Augustus and the Sibyl, 1483-85, fresco, Santa Trinita, Florence

The idea that the Tiburtine Sibyl predicted the coming of Christ was a medieval legend with late antique roots, but it became extremely popular in the Renaissance. Hebrew antiquity seemed culturally barren compared to Classical antiquity, but the theological status of the prophets meant it had a unique relationship to Christianity. But if God revealed Christian sources to pagan seers as well, humanist study leveled up in a metaphysical way.

But there is a critical difference. Christianity is explicit that the Fall cannot be undone in this world, and that restoration to perfection only happens after death. This is an individual process; the lost state of grace cannot be restored by human means. The humanists begin by distinguishing their interests from the spiritual and propose a cultural rebirth in human areas that are not theologically determined. But as we see with Valla, it is inevitable that their new epistemology clash with the old, and as the fifteenth century progresses, this reached the point where classical authors become definitive in religious matters, thus changing the culture. In the wildly creative humanism of High Renaissance Rome, mythology, philosophy, literature, and magic combine with religion into a bizarre synthesis that promises a restored Golden Age in this world. We can guess how that ends.

The most important development in late fifteenth-century philosophy was the revival of Christian Platonism, based on Hellenistic Greek sources brought by Byzantine emigre scholars. Marsilio Ficino (1433-99), a Florentine humanist in the Medici household, was at the center of this movement, with works like the Platonic Theology attempting to harmonize this Neoplatonic thought with Christianity.

Marsilio Ficino, Letters, Presentation copy for Cardinal Francesco della Rovere, Florence, 1475/76, Vat. lat. 1789 fol. 5v-7r

This is a collection of writings on Platonic themes to one of Ficino's patrons, the future Pope Sixtus IV, who founded the Vatican Library and built the Sistine Chapel. Click for an extensive collection of humanist manuscripts from the Vatican Library.

Humanism reached the highest circles.

Filippo de' Barbieri, O.P., On the Discord between Jerome and Augustine, Settled Using Dicta of the Sibyls and of all the Gentiles, both Prophets and Ancient Poets who Prophesied Concerning Christ, Rome: Johannes Philippus de Lignamine, 1481

In this next text, we see a Dominican Platonist, a member of Aquinas' own order, appeal to pagan sibyls to settle a dispute between Fathers of the Church Jerome and Augustine. It was dedicated to Sixtus IV, the most important figure in the establishment of Renaissance humanism in Rome.

When the very epistemological foundation of cultural authority changes, it is inevitable that the culture changes as well. What possible Christian grounds could pagan sibyls have to adjudicate a theological dispute? But here is the pope presiding over the production of doctrines that are fundamentally un-Christian. This should seem familiar, both in the general way that the globalist left warps cultural institutions, and, more specifically, in the current occupant of the Holy See.

An idea developed in this environment that Ficino called prisca theologia, or ancient theology, which broadened pagan authority within the Church. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought a trove of lost Greek manuscripts and skilled language teachers into Italy. Not only Plato, but a full selection of Hellenistic sources, which brought the weird world of late antique syncretism back into the West. Suddenly antiquity became much broader and more esoteric, as quasi-mythical sages like Zoroaster and Hermes Trismagistus jockeyed with late Neoplatonic mystics in the minds of humanists lacking any historical framework for processing this material. Antiquity was established as an authority, but now the question became, which antiquity? The answer: all of them.

Hermes Trismegistus, anonymous floor inlay in Siena Cathedral, 1480s.

No one captures this esoteric, syncretic humanism like Hermes Trismegistus, or Thrice-great, an imaginary fusion of the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth. His writings were thought to be the original source of pagan wisdom because of the Neoplatonic content, but they turned out to be late antique fakes, and their Neoplatonism cribbed from Greek sources. Prisca theologia never recovered from the this debunking.

The basic concept behind prisca theologia is that the Christianity is not a singular revelation - the actualization of Old Testament prophacy - but the most perfect in a series of them. Pagan thinkers like Hermes, Plato, or the Sibyls had access to divine wisdom, only in a more impure form. Christ remains the indispensable means of salvation - even these humanists are staunch in their belief in the Incarnation - but the Old Testament has to make way for other revelatory sources. Of course, this means clever humanists are required to synthesize the growing number of ancient texts with Christian doctrine. Only, without any external authority or standard, how is a meaningful synthesis possible? Once authority or standards are upended, proponents of the faith have no rational defense against other heresies. The idea that Christianity can be whatever we want is another thought pattern that is too common today, both in terms of religion and truth in general.

Dome of the Rock, 687-91, Jerusalem

Once the Bible is merely the best in a series of revelations, it is no longer absolutely metaphysically singular. Logically, what is the defense against claims of another, still more perfect revelation? That was the position stakes out by Islam centuries earlier; how does a humanist embrace prisca theologia and logically reject the Islamic claim that the Koran represents a still more perfect account of God's word? By making theology humanistic, that is, literally the province of human activity, the central authority in Christendom ushered in relativism and rendered their claims to universality incoherent.

In the hands of Renaissance popes, humanist syncratism became a propaganda tool to present the papacy as the culmination of a unified world history, with all of antiquity pointing to the coming of Christ, who establishes the Church as the ultimate spiritual authority. When it came to evaluating these pre-Christian "sources", the humanists were shaped by their own attempts to cut through the distortions of history and restore ancient texts to their original form. This lent itself to the notion that the older something was, the more pure or better than newer iterations. Age equaling authority is not a stretch for people who defined their own ethos through cultural revival, followed a religion based on an original fall from grace, and were steeped in the classical myth of the Golden Age. By this standard, sources dating back before Moses, like the supposed Hermes, had real weight in humanist circles.

Pinturicchio, Room of the Saints, 1492-94, Vatican. The ceiling shows scenes from the Egyptian myth of Osiris and Isis.

Osiris, a resurrected god, was appealing to humanists as a pagan type of Christ. The choice of this decorative scheme in the private apartments of the notorious Borgia pope Alexander V indicates its appeal.

This rhetoric feeds the papal fantasy of the dawning of a new Golden Age of spirit, where ancient wisdom can enrich scriptural understanding and create as perfect a state as possible in this world. But the rhetoric is empty. The Borgia were tyrannical and corrupt, and their successor and greatest patron of the Renaissance, Pope Julius II, was not known to be personally venal, but spent enormous resources on realizing this vision through works of art and architecture. If Julius didn't think there was something to this humanist "theology", why have Michelangelo alternate Hebrew prophets and pagan sibyls on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel?

Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508-12, fresco, Vatican; Delphic Oracle, Libyan Sibyl

The Delphica stares into the future, while the Libica is a model of sinuous grace.

The Delphica stares into the future, while the Libica is a model of sinuous grace.

There are some conclusions to be drawn from the rise of the humanist movement and the end of the unified vision of the Middle Ages. To change a culture, you must change its values, and that can be brought about by introducing new authorities that not only cast the old mores an one possible assumption, but an outdated, inferior, backwards one. Change implies directed movement, and movement in line with a new belief system is pretty much the definition of progress. The humanists thought they were progressing into a new enlightened age, and while their dream collapsed, the idea of human driven progress through an ever-shifting group of cultural "authorities" towards an incoherent, imaginary "ideal" continues to plague us.

The humanist introduction of "classical" authority had an enormous impact on the development of the visual arts. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Western concept of "art" was born from the primacy of ancient sources and dream of progress towards an alien external standard of perfection. More precisely, the art theory, or the notion that art is defined and classified according to a set of unchanging first principles is a humanist invention. This has several components:

Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504, marble, 5.17-metre (17.0 ft) ...

Location: Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence

We can see the similarities between Michelangelo's famous statue and the ancient works that it drew from. The nudity in particular is striking for what was intended to be a prophet. Michelangelo captured the idealism and posture of the Roman sculptures, but with even greater realism.

Ancient theory is more important long-term. In reading classical sources, humanists encounter entirely new ways of thinking and writing about art. This leads to the development of theoretical principles that define "art" and provide a standard to make comparative judgments. The theorizing of the arts had enormous consequences for the shape of Western culture. It raised the status of the artist from medieval craftsman to modern "genius" or "visionary", but did so by narrowly defining what kinds of images are "art". The Western tradition of the Fine Arts began when painting, sculpture, and architecture were singled out and provided foundational theories that conformed to humanist principles. All three arts combined Renaissance idealism and classical authority, but did so in slightly different ways.

Painting was the least known of the ancient arts, since nothing survived for Renaissance painters to look at. They did copy sculpture for figure types, but the Classicism of Renaissance painting is more theoretical, since it was based on textual accounts rather than visual models. Here, what mattered was the impression of classical "values" rather than the look of Roman art, since they really didn't know what that looked like.

Polyphemus and Galatea in a landscape, from Boscotrecase, end of 1st century BC, fresco, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Raphael came to be considered the ultimate "Classical"painter from his structured compositions, clear linear style, and idealized forms. But his work looks very little like actual ancient painting

Raphael came to be considered the ultimate "Classical"painter from his structured compositions, clear linear style, and idealized forms. But his work looks very little like actual ancient painting

Sculptors had lots of antique statuary to look at, so their figures are closer to the ancient prototypes, but still had to be adapted to contemporary taste and Christian culture. The David is perhaps the archetypal example of a classically inspired figure, but with the enhanced realism of the expression and anatomy that is a product of Renaissance theorizing more than actual ancient models.

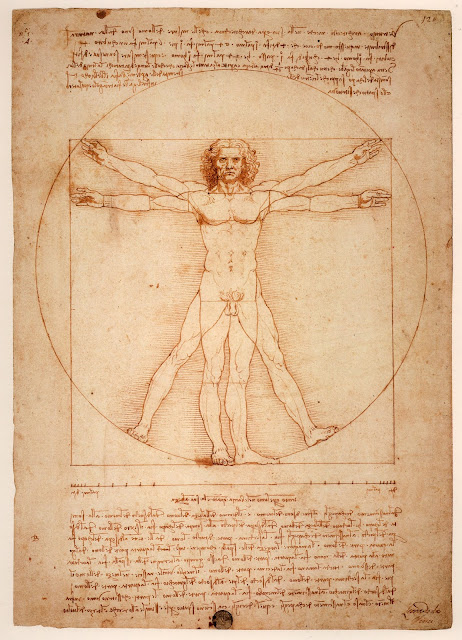

Architecture is the fine art that follows closest to ancient models theoretically, since Renaissance humanists has abundant material evidence as well as Vitruvius to guide them, It is not a true classical revival, since the buildings are adapted to new forms, but it does combine the orders with a notion of Neoplatonic symbolic geometry that is intellectually consisitent with Greek architectural theory. It is this geometric abstraction that makes these buildings the true forerunners to Modernism.

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) represents as radical a shift in architecture as Petrarch did in letters, with his introduction of a simple, rational classicism consisting of basic proportional relationships and Greco-Roman detailing.

Andrea Cavalcanti, Monument to Filippo Brunelleschi, 1447-48, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

The bust is taken from a death mask, so the likeness is good, Brunelleschi was a genius polymath, surpassed only by Leonardo among Reniassance thinkers, and his influence on the shape of Renaissance visual culture cannot be overstated. In addition to his revolutionary architecture, he also seems to have invented linear perspective in drawing and painting. He was an integral part, perhaps, along with Donatello, the integral part, of a somewhat unbelievable collection of talent (Ghiberti, Masaccio, Alberti, and others) that created Renaissance art in Florence.

Arnolfo di Cambio, Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore), beg. 1296, Brunelleschi's dome, 1420-36

Brunelleschi completed the Duomo by figuring out new construction techniques to construct an unbuttressed dome over the cavernous crossing. This made him a local legend, and the dome was celebrated by humanists as proof of the greatness and ingenuity of the Florentine people.

Technically, his solution was innovative, but stylistically, he was bound by the Gothic style of the partially finished building. Brunelleschi's dome is elliptical rather than spherical, which made it stronger and hinted at a pointed Gothic vault. He maintained the traditional medieval Florentine colored stone paneling on the exterior as well.

The Duomo made Brunelleschi's reputation in Florence, and brought him new architectural commissions where he could design the projects from scratch. Freed from restrictions, his buildings were radically new in style, essentially a visible version of the new cultural authority of the humanists. Although Brunelleschi never wrote an architecture treatise, his approach to architecture was highly theoretical, which further distinguished it. We understand Brunelleschi's thoughts through the writings of the younger Alberti, an architect and humanist scholar who actually articulated a humanistic architectural theory in his later writings. But we can infer a lot about Brunelleschi's humanist principles through his radical buildings.

Brunelleschi, Santo Spirito, designed from 1424, begun 1446, Florence

Brunelleschi's architecture employed simplified basic forms to create an impression of perfect clarity and harmony. The brightly-lit interior, limited cool color scheme, and clean decorative lines are quite unlike Gothic buildings. The overall impression is one of reasonable, tasteful order. Note the return of the classical orders with the Corinthian columns.

Santo Spirito was built to a simple modular design. The interior decoration was based on mathematical proportions, which was not fundamentally different from Gothic architecture, but the appearance evoked the feeling of Classical notions of harmony and proportion. The lay-out is basically a purified ancient basilica, with a greater emphasis on clarity.

Santo Spirito doesn't resemble any particular ancient building, but to humanist eyes, the sharp geometric clarity and harmonious proportions captured the spirit of antiquity. For his part, Brunelleschi studied Vitruvius and surveyed the monuments of ancient Rome.

Is it fair to say Brunelleschi had an architectural theory? The notion of an essentially Neoplatonic architecture based on simple proportional relationships comes from Alberti, and his ideal ratios aren't actually that common. But the lucid organization of forms and the use of decoration to highlight structural aspects of the design is consistent in all his work.

We can see this outlining of the structural elements in the dome, where the supporting ribs are clearly marked. Ribbed domes on pendentives go back to late Roman/early Byzantine architecture, with the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople being the most prominent. Brunelleschi liked them for the simplicity and clarity of their circular form, which, much more than the elliptical dome of the Cathedral, suited his humanistic ideals.

Compare Santo Spirito with his domes for the Pazzi Chapel and the Old Sacristy in San Lorenzo, both in Florence. Structurally and aesthetically, they are virtually the same. It is this consistency in the simplicity and structural clarity that suggests that Brunelleschi was guided by an underlying theory.

Brunelleschi's architecture was as radical in its dismissal of the old order as humanist scholars were of the medieval Scholastics, and his "authority"also came from the same place. The clarity, simplicity, and proportion of his work was based on classical antiquity, a culture quite alien to fifteenth-century Florence, but this distance is what allowed it to assume the position that it does in Renaissance thought. This classical architecture was not something that developed organically, but was put together by a network of individuals who felt that they had found the secret to truth in some old manuscripts. Ultimately, they hadn't, but their legacy changed building forever.

If outlining structural members and simple geometric clarity sounds suspiciously Modernist, it should. This is where it starts. In the next post, we'll see how it gets there.

| |||

Leonardo, Vitruvian Man, circa 1490, drawing, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

|

No comments:

Post a Comment