If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right.

The previous post took a new look at the Renaissance from the perspective of cultural authority. We traveled back to fifteenth and sixteenth-century Italy to see how architecture came to be dominated by the ghastly crimes of Modernism and its descendants. What we found was that the invention of architecture theory, or what a Postmodernist would call discourse, was simply a sign of a deeper cultural transformation in the West. It turns out architecture is a fine vehicle for thinking about these larger historical issues because it is the way by which the social and intellectual elites shape our physical environment. More simply, architectural theory reflects the fallacies and deceptions of contemporary thought.

A good example of facadism, this building keeps the 1895 facade of the Cardiff Gas Light and Coke Company, but destroys the rest. The contrast between the ugly modern mass and the elegant Victorian design is striking. This is a Postmodern vision of tradition; something that is cool to look at and worth remembering on that level, but devoid of substance and disconnected from the Modern world.

What happens in the Renaissance is that building divides into theoretical and practical aspects. This is significant, because it means that the traditional factors that went into designing spaces - practical function, individual and cultural tastes, symbolic messaging - became subordinate to an imaginary higher universal ideal. It is one prominent example of the Renaissance introduction of secular transcendence, the claim that finite human intellect can reach transcendent truth through purely material means, that began the long march to Modernity. Leonardo da Vinci, one of history's great intellects, connects these concepts visually.

Leonardo's famous Vitruvian man expresses the Renaissance humanist flavor of secular transcendence. The essence of the universe is expressed in simple geometric harmonies, following the Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists, which correspond to "ideal" human proportions. Man is the "microcosm", created in God's image, and therefore privy to truth at the level of divine knowledge. It is seductive and empowering, especially when visualized by artists of Leonardo's caliber, but it is absolute twaddle as philosophy, history, or theology.

Leonardo, Illustrations from Luca Pacioli's De divina proportione, composed circa 1498 in Milan, published in 1509 in Venice.

As the title indicates, this book took the humanist position of Neoplatonic geometry as a pure expression of higher truth. This is a more in-depth investigation of the simplified metaphysical relationship depicted in the Vitruvian Man. For a good look at the math, click here.

Leonardo innovated a new way of rendering the polyhedra as cages to show their structure more three-dimensionally.

Leonardo, Studies for a Building on a Centralised Plan, circa 1487-1490

The direct link between sacred geometry and architecture made by Alberti appears in Leonardo's concept drawings for harmonious centrally-planned churches. Leonardo never designed actual buildings, but there is a compelling argument that he influenced Bramante in Milan. It is easy to see the resemblance between these sketches and Bramante's later plan for St. Peter's.

The notion of a theoretically pure architectural theory is just an extension of the larger humanist belief that they had uncovered a wellspring of secret knowledge that would unlock the secrets of the universe. As we saw, this fantasy grew out of the early Renaissance establishment of a new and alien authority - antiquity - within organic medieval cultures. What began as a suppliment to theology became a replacement, as even the Renaissance popes expressed hope for a Christian humanist Golden Age in this world.

Michelangelo, Holy Family (Doni Tondo), 1505-1506, tempera on wood, 120 cm, Uffizi, Florence

In this early painting, Michelangelo already shows his grasp of complicated poses. But the iconography is strange. The distant nudes have been interpreted as representing the pagan world outside Mosaic Law, John the Baptist at the fence stands for the Old Testament world under Law, and The Holy Family the Golden Age of Christian Grace. Renaissance theologians called these ante lege, sub lege and sub grazia.

Michelangelo was exposed to humanist thought during his time in the Medici household as a youth.

The empowerment and wisdom offered by this knowledge was catnip to human vanity, as it always has been.

William Blake, Eve tempted by the Serpent, 1799-1800, tempera and gold on copper, Victoria and Albert Museum

Claiming knowledge beyond human scope is the recurring, as well as the original, sin.

The problem with the humanist theorizing of the Renaissance is the problem with all secular transcendences: they are lies. Claims like ideal geometry or the patriarchy depend on a philosophical bait and switch, where they claim to be something completely different from what they are, but expect to proceed as if the former were reality. Here, theory professes absolute universal objectivity while actually being a purely subjective reaction to specific historical conditions. Unified cultures develop attitudes organically over time as new ideas are filtered through informal networks. The authority of "antiquity" in all its countless permutations, is the opposite, a top-down imposition of opinion masquerading as rules, which makes it an important structural forerunner of Modernism.

Models of Authority

We saw two forms of architectural authority emerge in the Renaissance (these apply to painting and sculpture as well): the aesthetic theoretician and the inspired genius. These are loose categories and are not meant to be definitive in any way, but they do capture the strange flavor of art world discourse.

Michelangelo, New Sacristy, 1519–24, San Lorenzo, Florence

In his first major architectural project Michelangelo responds to Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy in color and classical architecture, but he incorporates sculpture and takes liberties with the decoration in unclassical ways.

Michelangelo is an archetype of inspired genius, though Brunelleschi or Leonardo could fit as well. These figures break "rules" but are permitted because they were recognized as having vision and talent beyond explanation or constraint. Giorgio Vasari, the humanist confidant of Michelangelo and the Medici and father of art history, took a halfhearted stab at theorizing genius in the mid sixteenth century, and came up with some vaguely defined terminology before chalking it up to divine inspiration.

Palladio, Villa Cornaro, 1552, outside Venice

Palladio's masterpiece has an unusual two story colonnade, but shows his usual simplicity and symmetry. Palladio's designs were innovative, but he followed a theoretical substructure that he articulated in his writings.

Palladio is an archetype of learned theoretician, with plans and ideas derived from antiquity and carefully recorded in treatise form. As noted above, these distinctions are not hard and fast. Palladio used his own genius to derive theory from ancient sources, while Michelangelo accepted the contemporary taste for classicism before creating his own variations. The distinction lies in the attitudes towards theory. Michelangelo was aware of architectural theory, but chose to follow his own imagination, while Palladio both followed and disseminated theoretical principles on antique authority. To make matters more complicated, the individual creations of an inspired genius like Michelangelo could provide raw material for the theorists to systematize by bringing truth into the world like aesthetic mystics. In a sense, creators like Michelangelo and Raphael became new or "honorary" ancients on the basis of their divine gifts.

Palladio, elevation and plan of Bramante's Tempietto from I quattro libri dell’architettura, Venice, 1570

Modern classics: Bramante makes his way into Palladio's treatise despite having lived within the same century.

The result is a flexible rule book for a narrowly defined field that is up to date and easily taught. But from a modern perspective, there is really no one in the academic community that believes in the authority of antiquity or divine inspiration in Christian terms. The question emerges: how does a system founded on two pillars that are no longer accepted within the system retain control?

Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, 1945-51

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, 1974-77, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

I.M. Pei, Louvre Pyramid, 1984-89, Paris

Rem Koolhaas and Joshua Prince-Ramus, Seattle Central Library, 1999-2004, Seattle

The move from Modernism to High-tech Modernism, to Postmodernism, to Deconstructivism are just moves in a theoretical game. There are no popular or cultural considerations behind these decisions.

The various Postmodernisms only reflected public taste in the most general way, by reacting against the monotonous polyhedra and cement blobs of Modernism. All their daring, bold, provocative, or whatever other misused adjective moves take place within the closed game of theory. This helps explain the remarkable insensitivity to the public, since the very act of opposing the theoretical game marks you as a philistine and likely an idiot.

To generalize, Postmodernism's big move was to reject the theoretical master narratives of Modernism as arbitrary rules, but it did so within, and while accepting, the larger theory-based structure of architecture as a discourse. Returning to the form/content analogy for epistemology in the last post, this can be thought of a content-level change without addressing the fact that the very institutional world of architecture was founded on the theoretical master narratives that the Postmodernists claim to reject. All the venues that make up architecture as a discourse - the schools, critics, journalists, non-profits - take the position that it is a hermetic intellectual space, distinct from the culture around it, that follows the lead of theoretical dogma and and the prophetic utterances of inspired genii. Postmodernism was simply subsumed into the classificatory logic of academic architectural history as a spot on the timeline. There is a larger lesson here.

Derrida's famous quote is actually true IF you confuse theoretical abstractions for reality. The answer, however, is not to to declare reality meaningless, but to ditch the constraining theoretical structures. The photo is from a typical site that "explains" deconstruction by uncritically accepting the authority of the incoherent Philosopher's Names that serve as its "foundation".

To reach the point where architecture is reduced to made men pushing pieces in a game of dehumanized theory, the Renaissance archetypes of authority - inspired genius and aesthetic theoretician - had to become universalized. In other words, the idea of architectural authority had to become ingrained to the point that the rationale behind the selection of individual authorities didn't matter. The old model is outdated? Plug in the next one. But the problem is that the very act of switching authorities proves that these aren't authoritative at all.

Michelangelo, Porta Pia, 1561-65, Rome

In his last architectural project, Michelangelo uses Classical forms, but deploys them in typically idiosyncratic ways. He also adds elements that are purely of his own invention like the hanging curves draped over the roundels in the upper story. There is no precedent for this anywhere.

Giovanni Battista di Quadro, Poznań City Hall, 1550-67, Poznań, Poland

Mannerism prefigures Postmodernism in that it accepts a basic theoretical definition of architecture (in this case Classical elements and artistic inspiration), but allows considerable freedom from rules within these framing assumptions. This made it easy to export Renaissance ideas without requiring buy in on the full epistemology of syncretic humanism. In this building, classical elements are applied to a very unclassical building, where the coexist with more local traditions.

Renaissance humanism was a localized Italian phenomenon, and even within Italy, Michelangelo and the Mannerists proved theory had no real binding power.

How did these ideas become universal?

The humanists, unlike their tradition-minded peers, wrote polemical treatises where their formidable rhetorical skills could puff up their views while savaging other perspectives. Although they were not "academic" in the eighteenth-century sense, they established the foundations of a powerful discourse, and spread their influence as advisors, patrons, and artists.

Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508-12, fresco, Vatican Museums

This famous ceiling builds on the fifteenth-century wall paintings to express a unified Christian humanist view of history. The Book of Genesis is the thematic backbone, but supporting Old Testament figures share space with pagan sibyls and shadowy nudes suggestive of antiquity. Given the complexity of the scheme, it is assumed that humanist advisors, likely Giles of Viterbo, aided Michelangelo with the program.

This gave them authority, but what did they do with it?

When we look back at humanism and the arts in the Renaissance, what we see the progressive shattering of the cultural bonds of Christendom.

Intellectual culture comes first, as the humanists attack scholasticism and the medieval universities. Their attack is rhetorical, using philology and ridicule, leaving the contorted dialectic of the schoolmen powerless. In its place they offer an attractive, uncritical, and incoherent pastiche of antique sources and their own linguistic creativity.

Laurentius de Voltolina, Henricus de Alemannia with his students, from the Liber ethicorum des Henricus de Alemannia, second half 14th century, parchment, 18 x 22 cm, Kupferstichkabinett Berlin, Min. 1233

The formalized intricate logic of the medieval schools was easily parodied as disconnected, irrelevant naval gazing.

Maximilian Sforza Attending to His Lessons, from the Donatus Grammatica, 15th century, vellum, Biblioteca Trivulziana, Milan, Ms 2167 f.13v.

Humanist education presented itself as personally worthwhile and keyed to better living in the real world. But we can see from Sforza's laurel crown, an antique symbol of ancient poetic triumph that the humanists revived in the Renaissance, that he has simply replaced one authority for another.

The value of antique sources is accepted uncritically, which, despite their florid rhetoric, leaves their project on the epistemological version of air.

Dialectical helplessness against rhetoric reminds the Band of the stern, yet ineffectual written rebukes by modern conservatives of leftist depredation, illogic, and moral bankruptcy. You can almost hear the foreshadowed whir of spinning bow ties.

Behold the rhetorical allure of Conservatism Inc. Longtime globalist uber-shill George Will sets a sartorial tone for his hapless followers. Consider the unfortunately named Dalton Glasscock, a chairman of the Kansas Federation of College Republicans who calls for common cause with Liberals, and James Allsup, the former president of WSU College Republicans whose involvement in organizing the Unite the Right debacle in Charlottesville speaks volumes about his value to a nationalist cause.

The lesson: tradition cannot be defended from rhetorically-driven activists by feeble dialectic and strategic idiocy.

Religious culture comes next. Scholasticism was also theology, and the removal of traditional authority paved the way for the syncretic blasphemies of High Renaissance Rome. This is most clearly seen in the destruction of Constantine's Old St. Peter's for what was essentially a classical temple.

Marsilio Ficino, Theologia Platonica De immortalitate animorum duo de viginti libris, title page, 1559, Aegidium Gorbinum, Paris

Ficino's magnum opus was written between 1469 and 1474 and first published in 1482 as an attempt to synthesize the recently rediscovered works of Plato with Christianity. While it is true that there are Platonic structures in Christian theology, these had been subordinated to Christian metaphysics in late antiquity. The notion that Plato could be directly authoritative on theological subjects like the human soul is an acceptance that transcendent truth is available through purely human means. While this wasn't stated openly, the consequence was that anyone with consensus or institutional support could claim certainty about things that in reality lie beyond human knowledge.

Stripped of traditional authority, the cultural unity of Christiandom splits with the Reformation, introducing a proliferation of new interpretations based on the readings of individual preachers and scholars. With Catholicism sharing Europe with various Protestantisms, the old question of whether you were Christian became what kind of Christian are you?

Hans Holbein the Younger, Christ as the True Light, c 1526, woodcut, 84 x 277 mm, Kupferstichkabinett, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel

Holbein contrasts Protestants following the word of Christ as recorded in the Bible with the various Catholic authorities who turn their backs on this light and follow their own council into the abyss.

The Reformation was humanist in epistemology, but its sources were different. Martin Luther (1483-1546) and others took the humanist approach of looking backwards to seek pure textual origins, but focused on the Bible and the Fathers of the Church, rather than pagan writers. They sparked renewed interest in the original Biblical languages and stripped away medieval customs as adulterations of pure apostolic Christianity. Of course, each had their own reading of what this would look like, since the driving forces behind all of them were flawed human interpretations.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam with Renaissance Pilaster (detail), 1523, oil on panel, 73.6 x 51.4 cm, National Gallery, London

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Portrait of Martin Luther (detail), 1529, oil on panel, 73 × 54 cm, St. Anne's Church, Augsburg

Erasmus' Greek New Testament appeared in 1516 and shook Christendom with its challenge to the Vulgate. Luther's German New Testament was published in 1522, putting God's word in the hands of the laity.

In Italy, the Reformation triggered a social crisis when, in 1527, largely Protestant troops of Emperor Charles V sacked Rome, killing and displacing a large portion of the population and besieging the pope in the papal fortress of the Castel Sant'Angelo. This brought an end to proud fantasies of art-driven Golden Ages, and made apparent the precarious place that Christian humanism and venal worldliness had left the Church.

Michelangelo, The Last Judgement, 1536-41, fresco, 13.7 × 12 m, Sistine Chapel, Vatican

Michelangelo's last contribution to the Sistine Chapel shows his signature mastery of complex anatomy, but the High Renaissance confidence in the humanistic vision of the world is no where to be found. The message is traditional: the dead are divided at Christ's command and the damned dragged to Hell.

The sheer existential despair in this figure is almost palpable.

The reaction to these challenges took some decades to crystalize, but when it did, it was transformative. The result was a spirit of reform within Catholicism that split between factions that wanted to seek rapprochement with the Protestants and those that sought a return to traditional values, only purged of corruption and heresy. The latter viewpoint prevailed at the Council of Trent (1545-61), which began an internal housecleaning sometimes called Catholic Reform or the Counter-reformation, and spun into a widespread cultural movement. The late sixteenth century saw the emergence of larger-than-life reformers like Sts. Ignatius Loyola, Teresa of Avila, and Charles Borromeo who spurred a renewal of orthodoxy and attacked moral laxity and worldliness within the Church.

Peter Paul Rubens, Saint Ignatius of Loyola, circa 1620-22, oil on canvas, 223.5 x 138.4 cm, Norton Simon Art Foundation, Los Angeles

Rubens was very skilled with light and texture, which he used to give his paintings a sense of drama and energy. Here he shows the founder of the Jesuits as a spiritual hero whose writings were informed by the light of divine inspiration.This is a very different vision than the syncretic paganism of the High Renaissance humanists.

The visual arts came under scrutiny, since the Protestants rejected them as idolatrous, and even the most aesthetically sensitive could see that Mannerist art had strayed far from clearly presenting the values of the Church. We see evidence of this reforming thought in the appearance of late sixteenth-century art that is stripped of showy artistry and delivers a clear, accurate religious message.

Perino del Vaga, The Nativity, 1534, oil on panel transferred to canvas, 274 x 221 cm, National Gallery, London.

This picture is crowded with oddly detached and even inappropriate figures. The individual in the back right is strange, and the contorted Christ-child is an inappropriate quotation of Raphael. It is typically Mannerist for its emphasis on "artistry" rather than a clear and inspiring message.

Federico Barocci, The Nativity, 1597, oil on canvas, 137 x 105 cm, Prado, Madrid

This picture captures the new spirit. The subject is the same but the emphasis is on clarity. The warm colors and lighting of Mary and Jesus creates a feeling of tender intimacy, while Joseph opens the door for the arriving shepherds with a strong diagonal marking an obvious narrative flow.

Catholic reform raised a new question in the birthplace of art theory:

what IS art?

By wading into what had been a theoretical sphere, the Church highlighted a huge distinction in the meaning of art that many today are unaware of. Most people, even those with little awareness of or interest in the visual arts, assume that art is made for some purpose, whether to decorate, provoke, set a mood, transmit ideas, stimulate thought, commemorate, etc. Historically, artistic practice has reflected this with designs and images that appeal to patrons and customers. This is also the Church perspective, which saw the arts as tools to teach and inspire. The Catholic reform movement is a complex one, because it juggles the incompatible impulses of spiritual renewal and an increasingly worldly institutional hierarchy.

Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola and Giacomo della Porta, Church of the Gesù, 1568-80, Rome

The mother church of the Jesuits returns to Alberti's old model of stacked colonnades connected by volutes, but with a much greater emphasis on the main entrance. It revives solid theoretical principles, but with a new, rhetorical emphasis on reaching out to the visitor. This is the sort of architecture that the Catholic reformers preferred.

For the Church, art was purpose-driven

From the perspective of humanist theory, the arts are very different. Here, they are considered on the basis of their internal aesthetic qualities with considerations of purpose coming second. Palladio's treatise, for example, differentiates between building types, but applies the same principles of harmony to all of them. Theoretical moves only make sense within their theoretical framework, a position that becomes formalized in the art world with the notion of the absolute autonomy of art as a cultural space.

St. Peter's from the rear, showing Michelangelo's centrally-planned vision, and above.

Michelangelo's plan, and Carlo Maderno's plan, pub. Filippo Bonanni, Numismata Pontificum Romanorum Templi Vaticani Fabbricam indicantia, 2nd edition, Rome 1715, tav. 17 and 28

So the fault line becomes apparent between theoretically autonomous and purpose-driven design. It is easy to see why the art world opted for the latter, since it stripped cultural authority away from patrons or representatives of the public, and placed it in the hands of the critics and other institutional gatekeepers.

Baroque Anti-Theory

The architectural style that develops as the Church recovers a sense of confidence in the seventeenth-century is referred to with the historically awkward term Baroque. The word was applied later, as a negative reference to a period of artistic error, by hostile critics in the following century. This critical attitude is itself another sign of incompatible definitions of art, since it was the very formal exuberance that made the Baroque a valuable rhetorical tool for the Church that was offensive to Enlightenment aesthetic sensibilities. Because the Baroque was not a clearly defined movement in terms of humanist theory, it is difficult to define, with regional variations spanning the globe. It is easiest to conceptualize it as an outgrowth of Renaissance architecture, in that it accepts the importance of a Classical, rather than Gothic language, but replaces the rational principles of clarity and harmonic simplicity with attention-grabbing rhetoric that served the aims of the Church. This meant that practical concerns like drawing visitors and inspiring feelings of devotion were more important than notions of aesthetic purity.

Carlo Maderno, Facade of St. Peter's, completed 1612, Vatican

Architecture as rhetoric. Maderno continued Michelangelo's series of Corinthian pilasters into his facade, but followed the example of the Gesù in increasing their prominence as you draw nearer the main entrance. The pilasters become more three-dimensional rounded engaged columns, and the a pediment crowns the central bays. But Maderno projects his facade forward in space as well, so that the central focus approaches you. This is a subtle break with the Renaissance notion of wall architecture for what architects call plasticity.

The facade uses classical forms, but attracting visitors while impressing the grandeur of the Church is more important than purity of form.

It is not fair to say that the Baroque lacked theory, it is just that the theorizing didn't extend to the fundamental nature of architecture, or architecture qua architecture. These designers shared assumptions about the importance of Classical motifs and the positions of the Church, but were more or less free to use the former to express the latter without formal constraints. The result was a burst of rhetorical creativity that mortified the rationalist critics of the Enlightenment and beyond.

So what is rhetorical architecture? Since it was not conceived in a systematic way, it is easiest to present a few general concepts that are present in varying degrees. This is not exhaustive, but does give a sense of the shift from Renaissance harmony to mystical wonder.

Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola, Santa Anna dei Palafrenieri, 1575, Rome

This design foreshadowed a key feature in the Baroque: a taste for more irregular shapes than the perfect geometries of the Renaissance. Vignola introduced the ellipse to church design, which maintained the central plan of the circle, but created a longitudinal effect reminiscent of a basilica. This changed the effect of the interior space by introducing a sense of shifting movement.

Restlessness has long been recognized as a feature of Baroque architecture that distinguishes it from the static perfection of the Renaissance. This is suitable for a Church that views this world as a state of transitory imperfection rather than something that holds the key to transcendent knowledge.

Movement in the Baroque goes beyond stretching geometry.

Francesco Borromini, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1633-41, facade completed by 1677, decorations by 1682, Rome

Borromini was the eccentric genius of Baroque architecture. The undulating facade of San Carlo inverts the curvature of the central bay on the upper story, but presents a unified sense of flowing movement.

Notice that despite the unusual form, the details are still Classical - Corinthian order - and the facade is symmetrical. Borromini was attacked by later critics for his capriciousness, but he saw himself as a follower of Michelangelo, using his own genius to creatively break the rules.

His designs were cost effective and eye-catching, which pleased his religious patrons, if not Enlightenment theorists.

The interior is a remarkable space, planned around a complex shape. Borromini follows Michelangelo at St. Peter's with a colossal Corinthian order to tie the whole together, but the flowing space is was as unique in architectural history as it is hard to photograph.

From below, the complex shape is outlined by the entablature before four arches transform it to a simple oval. The symbolism of complexity resolving in heavenly unity is very appropriate to a church, if not a Classical treatise.

Other Baroque architects experiment with dramatic lighting effects.

Pietro da Cortona, facade for Santa Maria in Via Lata, 1658-62, Rome

The columns screen deep recesses in this facade,creating mysterious pools of shadow in the heart of an otherwise planar facade. Evocative lighting challenges the Classical emphasis on clarity, while voids in the center of a rectilinear mass violate the integrity of the form.

From the perspective of the Chruch, what mattered is that the effect was a mystical allure.

Designers try and suggest the infinite, both with architectural forms...

Guarino Guarini, Cappella della Sacra Sindone (Chapel of the Holy Shroud), 1668–94, Turin

The Shroud of Turin is housed in a fascinating structure that uses a complex form and tricky lighting to appear to open into a luminous unknown.

... and with painted illusions that make it look like the interior opens into a heavenly vision:

Andrea Pozzo, Triumph of St. Ignatius of Loyola, 1685, Sant'Ignazio, Rome

The illusion only works from the right viewpoint, but when you are there, the illusion snaps into focus. This is a good metaphor for Christian doctrine. It also undermines Classical clarity and distinctions between art forms.

For all their grandiosity, Baroque representations of divine glory have a humility in that they do not attempt to show what lies beyond human comprehension. The transcendent is suggested by a amorphous brightness, whether painted or structural, that shines into the holy space of the Church, but cannot be seen directly. The less humble aspect of this process is the place of the Church in this rhetorical performance. The correct point of view is only found through the Catholic perspective on Christianity. Baroque architecture served the church, and not the theoretical imperatives of humanists and critics. For now.

Pietro da Cortona, Santa Maria della Pace facade and restoration, 1656–67; cloister by Bramante, 1500-04, original built 1480-82 by an unknown architect

Architecture becomes theatrical, and seldom more than here. Pietro creates a tiny plaza with the wings of the building like those of a stage.

This theatrical arrangement is clear in the plan and from different viewpoints.

Illusionistic ceilings and theatrical lay-outs are attempts to draw on other art forms to enhance the rhetorical power of the architecture. But nothing antagonized the Enlightenment critics like the Baroque blurring of boundaries between distinct arts. The whole humanist elevation of the visual arts was based on giving them theoretical foundations, and this meant that they had to be clearly defined. The Church was less concerned with theoretical purity than rhetorical impact, so we see architecture become a sort of theater, where art, sculpture, and decoration create an almost mystical experience.

Gianlorenzo Bernini, Sant'Andrea al Quirinale, 1658-70, Rome

The porch for this Jesuit novitiate church uses a Classically-derived form, but projects forcefully, and the basic plan is an oval.

The interior uses red marble and gold gilding to suggest a worldly life of martyrdom and a heavenly reward. The altarpiece focuses this theme with the Crucifixion of St. Andrew, while the saint's soul rises through the barrier to the light.

Theatrical architecture isn't just a metaphor. A hidden light well makes it seem like the painted St. Andrew is illuminated by a mysterious source. The formal integrity of the architecture has just become a narrative prop; note how the pediment is broken to let the soul through. This is not an exercise in theory, but a simulated experience of the glory of salvation. All the art forms are subordinated to that goal.

The Baroque catches on a bit later in the Catholic parts of Northern and Central Europe, where the creative flexibility of the style was easily adapted to local taste.

Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, Kollegienkirche (Collegiate Church), 1694-1707, Salzburg

This church has the projecting curves and oval forms of the Italian Baroque, but the massing and decorative style are Austrian.

Egid Quirin Asam and Cosmas Damian Asam, St. Johann Nepomuk (Asamkirche), 1733-46, Munich

The Asam brothers combined painting, sculpture, and architecture in a way that recalled Bernini, but with much more decorative richness and almost no Classical influence at all.

The variety makes Baroque architecture fun to look at, but we've seen enough to get a sense for, despite some Classical elements, how anti-Classical this rhetorical approach was on a theoretical level. The change came as the center of European culture moved from the Church to the monarchies, with the Sun King Louis XIV leading the charge.

Baroque Power

Hyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait of Louis XIV in Coronation Robes, 1701, oil on canvas, 277 x 184 cm, Louvre, Paris

The Sun King ruled for a whopping seventy-two years, during which time he implemented an unprecedented level of authoritarian control in France. Culture was also brought under royal control, with the founding of the various French Academies of language and the arts. By setting the tone for the aristocracy and requiring academic training for access to patronage, Louis came closest to establishing official artistic styles.

The Académie royale d'architecture was founded in 1671, twenty-three years after the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture institutionalized the other humanist fine arts. These bodies developed into combinations of restrictive professional organization, lobbying group, and learned society, bringing unprecedented centralization of theory and practice under the direct control of the founder of monarchical absolutism. The Academy was even provided a headquarters in the royal palace of the Louvre, where they had easy access to the king and his ministers.

François Blondel, Cours d'architecture enseigné dans l'Académie royale d'architecture, P. Auboin et F. Clouzier, Paris, 1675-83, p. 204

Blondel was the first president of the Academy. In this image, he imagines an impossible origin of Architecture as an art in both "Nature" (as understood in seventeenth-century terms) and the organic culture of antiquity. Humanist theory was build on these contradictory foundations.

The Academies presented themselves as learned bodies in the manner of Renaissance humanist circles, but were much more formally established. Humanist "academies" were informal gatherings around noted individuals in the homes of supportive patrons, while Louis' creations had the institutional permanence of a government ministry. This continuity allowed Academic theory to cement its control over time, eventually reaching the point where the Academies became more or less synonymous with their arts in the minds of the general public. This is important, because it reveals the continuing philosophical bait and switch at that we first saw in humanist rhetoric, where a historical reaction is passed off as a set of objective first principles.

This means that while the academicians were blathering about theoretical primacy, they were actually constructing an ideology that expressed the personal cultural politics of the king. Louis understood Andrew Breitbart's famous quote that "culture is downstream from politics" and very deliberately promoted a particular style to represent his ambitions. This is where the reactive nature of Academic theory becomes apparent, because Louis had to define his architectural image in terms that were recognizable, but individually distinct. As was typical of French royal culture since the early sixteenth century, this was conceived in Italian terms.

Pierre Lescot, Lescot Wing, oldest part of the Louvre, 1546-51, Paris

The basic style of French Renaissance architecture is Italian Mannerism - note the free use of Classical elements - with the distinct French pitched roof and dark stone.

The dominant artistic style in Italy in Louis' time was the rhetorical, expressive Baroque, the perfect vehicle for the mystical grandeur of the Roman Church. Louis recognized the value of architectural rhetoric, but saw the Italian Baroque as too strongly associated with the papacy politically, and excessively spiritualized for a secular court. The result was a more rationally harmonious rectilinear classicism, but with a heightened boldness and grandiosity compared to Renaissance forerunners.

Pierre Alexis Delamair, facade and cour d’honneur of the Hôtel de Soubise, 1705-08, Paris

Note the almost Palladian simplicity of the facade, with its classical portico. But there is a greater boldness in the forceful projection of the double columns, while the heavy stone adds a sense of monumentality. Decorative stonework around the windows adds an element of Baroque ornament, but in a restrained, rational way. The pitched Mansard roof is a hallmark of traditional French architecture. But look how much more assertively the columns define the entrance when compared to the Lescot's Louvre design.

This style is sometimes confusingly called French Baroque Classicism.

Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Church of Les Invalides, 1677-1706, Paris

Autre plan de l'église des Invalides où sont marqués les compartiments du pavage de marbre, 1698-1701, ink, wash, and watercolor on paper, 126.6 x 82.4 cm, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Religious architecture follows the same pattern. Hardouin-Mansart designs a centrally planned church around the basic circle and square in the manner of Michelangelo's St. Peter's. But the bold portico projects forcefully outward, meeting the visitor and creating dramatic pools of shadow.

The Academy, which marched in lockstep with the king's wishes, produced theory supporting this more Classical Baroque over the version preferred by the Church. This meant returning to the theoretical idealism of the Renaissance, but repackaged as expressing "reason" rather than the caprice and emotionalism of the Church.

Bernini, designs for the east facade of the Lo

uvre, 1664-65

Claude Perrault, East facade of the Louvre, 1667-70, Paris

Perrault was an academician who had translated Vitruvius. The rejection of Bernini's flamboyant Baroque designs for his strict Vitruvian Classicism is one of those symbolic moments where Louis declared French independence in architecture.

If this sounds familiar, it is because the basic opposition of a "reasoned" Classicism and a "emotional" Baroque defined the grounds for Enlightenment-era Academic attacks on the Church as mired in illogic and superstition. This is easily overlooked because the Enlightenment was hostile to monarchy as well as Church, but this is where the institutional continuity of the Academies is important. The times changed, but the faith in the objectivity of theory remained constant, carrying the Renaissance vocabulary of reason into a very different context. Our form-content distinction is important here, since the academicians of the Age of Reason were openly hostile to the Renaissance faith in ancient authority.

The Battle of the Books, woodcut accompanying Jonathan Swift's "Battle of the Books", a prologue to A Tale of a Tub, London: John Nutt, 1704.

The noted satirist takes a stab at the intellectual quarrel between supporters of ancient and modern authority.

But on a deeper formal level, this debate played out in a technical language, a discourse if you will, that was established in the Renaissance. The result is that the Enlightenment hysteria towards the expressive forms of the ancien regime was articulated in the same language as the triumphalist rhetoric of the Sun King.

Why this matters:

For theory to dominate the arts, centralized control of a defined discourse is required. The Renaissance humanists established well understood boundaries for the three fine arts - Alberti had singled out painting, sculpture, and architecture in the fifteenth century - and the importance of antiquity as a cultural model. The French Academies provided the political mechanism for these ideas to become authoritative, but without central control like Louis', there is no why to impose this. We don't have kings in the academies today, but a monolithic globalist ideology performs a soft power version of the same thing. Even this may be soft-peddling the situation when we consider the links between the arts, education, cultural Marxism and the global elite. The lesson:

The roots of globalism are just that - roots - so the parallel between Louis' Academies and the contemporary art world are not exact. The French king had no intention to abolish nations; what he wanted was for his nation to be the cultural leader of Europe by taking the Italian humanist ideology and forging it into the expression of a unified, absolutist economic, political, military, and cultural program. The irony is that despite this extreme nationalism, the academic theory promoted by Louis' academies is a globalist Trojan Horse, because it is a top-down imposition of foreign ideas with no roots in French culture. What is there to prevent any ambitious patron from adopting the same program?

Palace of Versailles, 1661-1715, and detail of Louis Le Vau's "envelope" of 1669-72.

Some descendants of Versailles:

Winter Palace, begun 1730's, St. Petersburg

Schönbrunn Palace, 1742-70s, Vienna

Palace of Caserta, begun 1752, Caserta, Italy

None of these relate to the native cultures of their nations. Instead, they all speak the same Classical language of imperial power that was established at Versailles.

Globalist elites have always had their own symbolic languages.

Louis' opposition to the Italian Baroque was couched in nationalist terms - France needs a French style - but his bombastic Classicism was only "French" oppositionally, by virtue of not being Italian. Put another way, it is not X because it has features positively associated with X, it is X only because it is not Y.

This is a Structuralist concept of meaning, where individual terms in a closed system are defined by their difference from other elements in the system, rather that a positive reference to anything external. It is therefore vulnerable to deconstruction, since, as a foundation, difference is easily reframed as nothing, as Derrida notably did.

The system that allows for this oppositional definition of "French" architecture is the theoretical notion of the arts that we have been following the last few posts. By establishing the idea that architecture has objective rules or principles, Renaissance humanists paradoxically paved the way for what would become the concept of an avant-garde by reimaging art in terms of "progress". The Modernists saw humanism as fundamentally conservative because it looked back to antiquity, but this is another content-level distinction. In terms of epistemological structure, or form, the Renaissance introduced the idea that art moves "forward" to break new ground, and that the most recent developments are the most important, or "best". What it meant to break new ground changed radically in the centuries leading to Modernity, but the conception of the arts as theoretically bounded cultural spaces that is driven by innovation and "genius" is constant.

Masaccio, The Tribute Money, 1425, fresco, 247 × 597 cm, Brancacci Chapel, Florence

Raphael, The School of Athens, 1509-11, fresco, 500 × 770 cm, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

Pietro da Cortona, Venus Appearing to Aeneas, 1631, oil on canvas, 127 x 176 cm, Louvre, Paris

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Antiochus and Stratonice, 1840, oil on canvas, 77 x 61 cm, Musée Condé, Chantilly

Claude Monet, The Ice Floes (Les Glaçons), 1880, oil on canvas, 97.2 x 147.3 cm, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont

Lee Krasner, Shattered Light, 1954, oil and paper collage on masonite, 86.4 x 121.9 cm, Private collection.

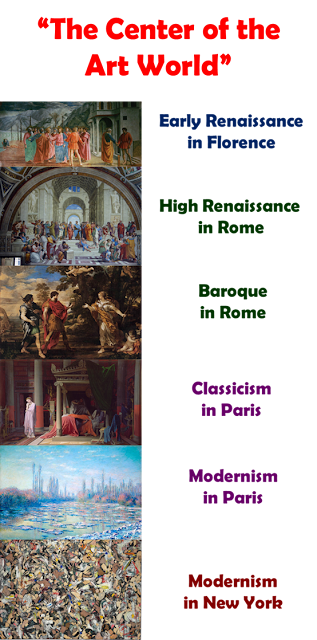

If art is is conceived as a defined discourse that moves forward (however that is defined), then it can be thought of in directional terms, which means it must have some form of leadership. Historians use the name "center of the art world" to refer the the place where, in critical hindsight, the dominant theoretical course for the arts was set.

The same loose trajectory is apparent in architecture. The last few posts have followed the movement of the center of the architecture world from its birth in Florence to Rome to Paris. In each place, the direction of the governing theory was set, according to the conclusions of historians and critics.

There is something attractive about the image of a free-floating body of theory detached from the messiness of daily politics; the pure art envisioned by the Renaissance humanists. Alberti, Palladio, and Le Vau all draw on Vitruvius to express very similar ideals. But the "theory" is a phantasm, a bait and switch that incoherently promises objective certainty in subjective opinion.

Note how different the work of these "Vitruvians" actually is. The underlying geometric principles and classical vocabulary are the same, but the overall appearances are quite different.

Theoretical architecture was always doomed by incompatible elements in its foundation: the worship of individual genius and the need to follow theoretical precepts.

The problem is that the center of the art world only exists if we accept that theory and practice are the same thing, and that is an empirical falsehood. And how does an empiricist demonstrate the false objectivity of theory? By watching what happens when the political authority propping it up disappears. Louis' death brought an enormous aesthetic backlash, since his successor Louis XV did not share the same interest in control and the aristocracy reveled in freedom from the king's oppressive artistic oversight. The result was the ornate movement known as the Rococo.

Germain Boffrand, Salon de la Princesse, begun 1732, Hôtel de Soubise, Paris

Remember the Classical facade of the Hôtel de Soubise? Check out the interiors. Boffrand's design is a pioneer of the Rococo style. Note the absence of Classical motifs in favor of more natural seeming forms. The light color scheme, avoidance of simple geometries, and ornate, integrated decoration are all antithetical to Louis' grand vision.

The Rococo also spreads from French aristocrats to their foreign peers.

François de Cuvilliés, Hall of Mirrors in the Amalienburg, 1734-39, Nymphenburg Palace, Munich

The similarity between this room, designed for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII and his wife, Maria Amalia of Austria, and the Rococo interior at the Hôtel de Soubise is obvious.

The Rococo merges with the late German Baroque to produce some truly spectacular churches.

Dominikus and Johann Baptist Zimmerman, Wieskirche, 1746-54, Wies, near Munich

So the Academies formed to push a French architecture that wasn't French, but Louis' example did make his forceful Classicism a symbol of authoritarian power, be that...

Pierre-Alexandre Barthélémy Vignon, completed by Jacques-Marie Huvé, Church of La Madeleine, 1807-45, Paris

...the Emperor Napoleon...

John Nash, Edward Blore, Buckingham Palace, remodeled 1826-37, London

...the British Empire...

Karo Halabyan and V. Simbirtsev, Red Army Theatre, 1934-40

Albert Speer, Model for the Volkshalle (People's Hall), 1939

...or the Third Reich.

Each of these "Classicisms" is different in detail, since they are the products of different times and circumstances, but the underlying association - the connection between Classical architecture and imperial power remains the same. At which point, critics and academics can slither in with another bait and switch to misrepresent the history for ideological reasons.

Gustave Dore, Satan, disguised as a serpent, approaches Eve, 1886, engraving for Milton's Paradise Lost, IX, 434-35, "Neerer he drew, and many a walk traversd / Of stateliest Covert, Cedar, Pine, or Palme."

This article is typical of the form/content split in academic history that allows for obvious objective falsehoods to fly under the radar. The author does an excellent job connecting the impact of Nazi architecture to rhetorical experience, easily passing the test of whether or not it improves your understanding of a historical phenomenon. But note the assumption at the end; that it was Modernism's avoidance of bombastic architectural rhetoric that made it the style of the "free" democratic world, as opposed to the traditionally symbolic architecture of the totalitarians and imperialists.

This take is superficial to the point of error.

The false assumption that the problem is symbolic architecture and not authoritarianism is a typical Postmodern move of mistaking a signifier for a signified, or a representation for the thing represented. This is an offshoot of their childlike faith that words have power over reality. The notion that architectural "discourse" is the same thing as architecture is the same magical "thought" process behind the idiocy that giving everyone a trophy will instill the same positive feelings as an earned achievement, or that admitting everyone to college with confer the economic rewards that graduates enjoyed when enrollment was limited to those in the 90th percentile of intelligence.

George Catlin, Medicine Man, Performing His Mysteries over a Dying Man (Blackfoot/ Siksika), 1832, oil on canvas, 73.6 x 60.9 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The idea that words and symbols have power over reality has always been common among the intellectually underdeveloped. In more modern times, where we actually have the means to understand that this is not the case, the appeal seems to have jumped to the emotionally underdeveloped (magical thinking as a tonic for reality) and the outright evil (magical thinking as a seductive alternative to reality).

Look closely at the "argument" - totalitarians use classical architecture, therefore classical architecture is bad, Modern architecture is anti-classical, and therefore is good. Structurally, or in terms of form, this is the exact same type relational definition masquerading as a positive identity that made Louis XIV's architecture "French". If Modernism is only "good" in relation to the specific aesthetics of Stalin or Hitler, it has no intrinsic moral value of its own.

F. Yuryev, L. Novikov, The Institute of information, 1971, Kiev

What if the Soviets switched to Modernism? Are their sins wiped away? A disturbing number of "Western" academics have ran interference for this bloodiest of ideologies since its hellish inception.

Ernst Sagebiel, Tempelhof Airport, 1936-41, Berlin

The Nazi's also had a taste for stripped-down architectural forms; does this suddenly make them more agreeable? Most academics would choke on this one, since, as living stereotypes about the arts and math, they demonize National Socialism, while ignoring the vastly bloodier and more costly international versions known alternatively as Marxism or Communism.

Formally, this concrete monstrosity was described by architectural legend Norman Foster as "one of the really great buildings of the modern age" but the ideological taint sent it down the memory hole. Could it be that Modernism isn't an intrinsic force for good?

What is certain is the symbolism of former Templar land used as a monument to Teutonic supremacism used to facilitate the invasion of Germany by German quislings.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Seagram Building, 1954-58, New York

Current events are making it ever more apparent that the "reality" reflected by the art world is a well-orchestrated globalist project, with Marxist myths of historical inevitability masking deliberate economic, media, and political efforts to deny human biodiversity and destroy organic national cultures. From this perspective, the theoretical "purity" of Modernism was a perfect means of expressing a featureless, infinitely fungible, commodified human existence. In anyone shocked that the person behind Mies' limitless budget for this iconic symbol of the shift of the center of the art world to New York was a scion of an elite globalist family with Rothschild ties and a life-long shill for the dehumanized cult of architecture theory?

None of us should be surprised that Modernism, like any other style, only has relational meaning, since it is obvious that the arts are rooted in subjective human preferences, and not arrogant theoretical imaginings. But the art world is based on theory; its very existence depends on the centuries-old idea that there is something "objective" that distinguishes "architecture" from the mere act of building. Within this imaginary construct, content matters, and styles can have moral weight. But how much do imaginary worlds matter? Who cares about coherence theories of truth when the structure within which they appear coherent is itself incoherent?

The problem isn't that Classical architecture is inherently authoritarian. The problem is that architectural theory has created the false illusion that objective morality in architecture is even possible. The problem is at the form level of the epistemology, where different contents come and go, but the fake foundation lives on, propped up on false faith.

Frontispiece to A History of the Art of Magic: Containing Anecdotes, Explanation of Tricks and a Sketch of the Life of Alexander Hermann by Telemachus Thomas Timayenis, New York: J.J. Little, 1887.

Modernists were just another wave of architectural fantasists, puffing out clouds of theory to obscure the transformation of building from cultural expression to the top-down imposition of a hateful, anti-human globalist ideology. That they would claim "morality" for their degradations is disgusting.

Now comes the twist.

The entire history laid out above - the development of architecture as a theoretical discourse and its deconstruction as shape-shifting wine in the same incoherent epistemological bottle - is a narrative. The Band's presentation is an exercise in curation, where select "representative" examples are chosen to tell a preconceived story. Renaissance humanism unfolded in a small pocket of Europe, and Louis' Academies were the first of their kind. Other narratives were unfolding elsewhere at the same time. Consider the history of England, where Renaissance ideas were slow to penetrate and fifteenth-century architecture retained a medieval cast.

Sir Edmund Bedingfeld, Oxburgh Hall, circa 1482, Oxborough

Henry VII Lady Chapel, begun 1503, London, Westminster Abbey, London

Little Moreton Hall, circa 1504-08 to 1610, Near Congleton, Cheshire

Sir Edmund's Tudor manor house with irregular massing and ornament that is clearly not "theoretical". Henry's addition to the royal abbey is a fine example of English Perpendicular Gothic, a technically difficult style, but one without the sort of abstract rules of the humanists. Little Moreton Hall is a superb example of Tudor half-timber architecture, an organic, or vernacular, style.

Clearly Classicizing elements appear around the end of the sixteenth century, in the prodigy houses of the late Elizabethan aristocracy.

Robert Smythson, Hardwick Hall, 1590-97, Derbyshire

Note the appearance of symmetry, regular windows, a colonnade on the lower story and balustrade on the roof, as well as the simplified massing compared to Oxburgh or Moreton Halls. These are clear signs of Renaissance influence, mainly trickling through France.

"Theoretical" architecture only debuts in the court of Charles I, a doomed monarch hopelessly under the spell of humanistic Italian culture. Charles' preferred architect, Inigo Jones (1573-1653), was a devotee of Palladio, and he used his deep knowledge of Renaissance theory to devise buildings and theatrical performances that articulated the king's cultural vision.

Inigo Jones, Queen's House, started 1616, largely built 1629-35, Greenwich

The Palladian simplicity of Jones' design outdoes Palladio. The design is a perfect double cube and the decoration kept to an absolute minimum.

Although he is not usually classified this way, Charles is something of a proto-globalist in his desire to emulate the universal artistic culture of the European elites. His French wife, massive Renaissance and Baroque painting collection, and whole-hearted embrace of humanist ideology mark his as someone looking to impose an alien culture on a uninterested people. The difference from Louis is that Charles' power was limited by the unique political and legal traditions of England, preventing the sort of absolutism seen in France.

The Execution of King Charles I, 1649, engraving, British Library Crach.1.Tab.4.c.1.(18.), London

It was Charles' introduction of "Papist" elements into the English church that galvanized Puritan resistance. His cultural ideals added fuel to the fire. The English Civil War ended with Charles' beheading in front of the Palladian Banqueting House designed by Jones.

English architecture follows the turmoil of the Interregnum and Restoration with a brief flirtation with the Continental Baroques...

Christopher Wren, St. Paul's Cathedral, 1675–1716, London

This landmark is primarily French Baroque in conception, although there are Italian and German elements as well. The dome is a variation on Michelangelo's canonical Renaissance original for St. Peters.

...before strict, theoretical Palladianism reasserts itself, this time as an "English" alternative to the Baroque styles of Catholic Europe. The English intelligensia had come to see themselves as distinct from the continent, with Newton moving England to the forefront of the Scientific Revolution, a growing empire bringing rising wealth and power, and the Industrial Revolution just around the corner. The philosophy of John Locke captured a unique English pragmatism that was popularly contrasted with the superstition and ignorance of European monarchism and Catholicism. The clean, harmonious architecture of Palladio seemed the perfect answer to the bombastic rhetorical grandeur of the various Baroques.

Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus; or, The British architect..., title page, vol. 1, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale, New Haven.

Campbell revived treatise writing in English architecture and did do on Vitruvian lines. His own designs were straightforward Palladian adaptations to English contexts.

Which brings us to the Earl of Burlington and the Palladian ideal in eighteenth-century England.

We've seen Burlington's Palladian Chiswick House. The Earl was exposed to humanistic ideas during a Grand Tour sojourn in Italy and was instrumental in promoting Palladian classicism in England.

By now the pattern should be familiar. Theoreticians like Jones, Campbell, and Burlington were seeking an "English" architecture that was only English by virtue of not being French, Italian, etc. But the underlying assumption that "architecture" is a theoretical space is exactly the same. The only difference is what specific appearance or arbitrary ruleset this theory takes on.

The sinister globalist nature of art theory is that all historical narratives lead to the same place. Once you start asking which theory, you are already trapped in the game. What we have uncovered here is the link between theoretical academic culture and absolutism; what remains to be seen is how the nationalist undertones of French or English classicism were replaced with the current totalitarian fantasy of universal arts. For that, a new villain has to enter the stage.

Charles S. Ricketts, Faust and Mephistopheles, circa 1930, oil on canvas, 117 x 90.5 cm, Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry

Hi Enlightenment!

No comments:

Post a Comment