If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

Time to pick up our journey back to the Armory Show of 1913 and the collapse of the art of the West. To quickly recap, we were trying to understand how the Western artistic traditions - the most diverse branch of world art in terms of media, approaches, and forms of pure technical excellence - rapidly degenerated into meaningless, ugly sludge around the turn of the 20th century. This proved to be a big question, so we had to start with some sort of working definition of what art is in the Western tradition. And this led us back to the roots of the West in general.

Ivan Welz, Ukranian Night, not dated, oil on canvas.

Art is an expression of a culture, a people, a nation, or some other grouping. It is how people visualize themselves and their relationship to the world around them, and transmit that knowledge to posterity.

The vast frozen landscape and small snug houses captured in this painting speak to a shared experience of the painter and his people.

Thutmose, Bust of Queen Nefertiti, 1345 BC, limestone and stucco, Neues Museum, Berlin

We can't experience the world of Ancient Greece or Egypt directly, but we can see the some of the same things they saw - at least to an extent. Like what a queen from almost 3500 years ago looked like.

Ancient art is far from perfect, but better than nothing. The problem is that old artifacts often turn up without context. But if we work with the historical record, we can often figure out what they were aiming for and what their priorities were. Having an artist's name from this far back is really unusual and testimony to Egyptian record keeping.

This means that understanding the arts of the West and the culture of the West are symbiotic efforts - they shed light on each other. Hence the decision to dive into the roots of the West and the meaning of the arts of the West at the same time.

This has been a big undertaking and not one with any pretense of being comprehensive. What we chose to do was to look at the three main historical pillars of the West in chronological order:

Raphael, detail from The School of Athens, 1509-11, fresco, Vatican Museums

1. The Classical tradition coming out of Greco-Roman antiquity. This encompasses the older forerunners - the legacies of Egypt and the Ancient Middle East. Basically the ancient inheritance as perfected by the Greeks and Romans.

Gustave Doré, detail of The Triumph Of Christianity Over Paganism,1868, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Canada

2. Christianity, in its different forms. The Band finds theological minutia counterproductive and a path to churchian corruption. The pillar is sincere Christian faith in the basic universal principles of Christian metaphysics.

Adolph Tidemand, Bridal Procession on the Hardangerfjord, 1848

3. The formation of the European nations. The first two play out in different national forms depending on the circumstances where they are adapted.

Perhaps the most interesting discovery was the parallel between the way the three pillars relate to each other and our earlier observations about what we can know and how we can know it [click for the post]. The Band worked out the basic relationship between a simplified ontological hierarchy - levels of reality - and the epistemological modes that they are known by. Here's the basic graphic:

Three levels of reality and three modes of knowledge in a unified ontological-epistemological formation.

Logos is the "vertical"axis tying them together. It's a Greek term without a single English translation because it manifests in different ways on the different levels. The Λόγος as mentioned in the Gospel of John on the top level, abstract logic in the middle, and circumstantially-applied reason at the bottom.

Here's the main post where we work it out.

Each of the three modes correspond to a historical pillar - Christianity accounts for ultimate reality and the objective basis of morality, the Classical heritage laid the foundation for Western abstract reasoning, and the nations developed in the messy and somewhat random circumstances of material reality. It looks like this [click for the post where it's worked out].

This was interesting enough that we sort of lost sight of the Armory Show or modern art in general for a while. But only for a while.

Johannes von Gmunden, diagram of the positions of the moon, from his German Calendar, illumination on vellum, Nuremberg, 1496

Other distractions have come up as well. Ongoing meditations on the nature of time will eventually compliment these pieces on the pillars of the West.

Pierre Blanchard, Symbols Of The Occult

And occult posts have continued to reveal just how intertwined modern culture is with what was traditionally thought of as sinister secrets and even black magic.

There were a few posts on The Silmarillion in there as well. This post will look at inherent problems in the foundations of the Western nations and how the monstrous globalist hegemony that we're pushing back against was prefigured almost from the start.

The last roots of the West post left off with Charlemagne and the Carolingians - the archetype of Western Empire, and the origins of what would become France, Germany, and several other European nations.

And Carolingian Europe gave us some significant issues to consider going forward. Here are two major ones:

Empire vs. nation.

Earlier posts have looked at the fundamentally immoral nature of Empire - the suppression of national identities by another group - and it's essential connection to Globalism. Globalism is just the predation of empire extended to a world scale. In the West and Near East, Rome endured as the model of empire for the civilizations that followed.

Gennadios Scholarios with Mehmet II, 18th century, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

Even the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II declared himself Kayser-i Rum, literally "Caesar of Rome". Here he is with the Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople Gennadios (Georgios Scholarios), who he raised with the appropriate Byzantine rite, and who in tern recognized him Roman Emperor.

But Charlemagne provided the homegrown version - an empire that came from European roots rather than something imposed from outside. Carolingian unity has inspired collectivists right up to the EU of the present day.

But it is not our intention to wade into the complex history of the push-pull between national and pan-national forces. This is too broad of a topic. Our purpose is to understand the implications for the arts of the West, and there is a very specific way that the imperal legacy of the Carolingians transforms the understanding of culture - visual and otherwise. This is the notion of "cultural backwardness" or more specifically, the claim that the organic culture of a people is somehow inferior and requires uplifting by outside experts and authorities.

Jean-Victor Schnetz, Charlemagne receives Alcuin of York who presents him with manuscripts, 1830, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris

There is nothing unusual with different social classes within a society developing their own cultural preferences - even their own cultures more or less.

Consider the lead definition from Websters - it's as good as any. Culture is a product of shared experience, and extreme class differences create different experiences.

But the Carolingian elite don't develop their own organic alternative culture. They import it from elsewhere.

This is the point that this post is fixating on. Not the idea that different social classes/groups within a people have cultures of their own, but that the elite class is hostile to their native culture and promotes an alien alternative. Arguably Charlemagne had to bootstrap the elements of civilization to stabilize post-Classical Europe. But what happens when the stakes are purely aesthetic?

That opens the path to globalism, way before anyone could have seen it coming. But the history is more complicated than that.

Church, monarch and the question of authority.

The Latin Church emerged as a unifying body in the post-Classical West - an "extra-national" institution that took on responsibilities beyond tending to spiritual needs. Education, literacy, diplomacy - things that the fragmented landscape of the Germanic migrations were unable to manage in the early centuries.

Kilbennan Monastery, ruins of tower and church founded by St. Benen, a disciple of St. Patrick, 5th century, County Galway, Connacht, Ireland

Irish monasticism was the first of the three main lines of Classical knowledge preservation, preceding later Arabic and Byzantine transmissions.

Rome was the hub of a comparatively learned pan-European network going back to the decision to send Augustine to Glastonbury. This will become a problem when the Church seeks to extend political authority outside the realm of spirit. But it took some time for secular aristocracy to reach a point where there could be a conflict. For the first millennium, the Church was the main game in town for cultural production.

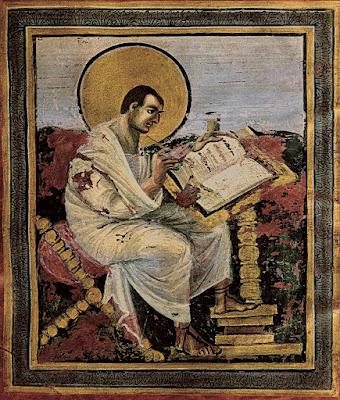

St. Matthew, from the Vienna Coronation Gospels, late 8th century Gospel Book produced at the court of Charlemagne in Aachen, Imperial Treasury (Schatzkammer), Hofburg Palace, Vienna

Art is an elite cultural activity by necessity. It is expensive, and if you want a high level of skill, the patrons and supporters have to have enough resources to support specialists who can devote their full time to skill development and production. In a primitive society where most people live subsistence lives, there aren't many places where there is surplus wealth to hire full-time artists or promote advanced training.

Charlemagne introduced imperial scriptoria to Europe, and most of the output was religious.

Leonid Afremov, Amsterdam, 1905, 2014, palette knife oil painting on canvas

In modern abundance society, more artists can support themselves outside of official channels. Selling prints is a good way to spread the cost of original work out around less wealthy buyers.

In Medieval Europe, high quality reproduction technology hadn't been invented, and there were relatively few places able to afford the luxury of full-time artists. Basically the Church and as the first millennium wanes, the developing aristocracy. Eventually, this will lead to a split - the same creators could take jobs from both, but the Church and aristocracy had different goals for the pieces that they commissioned. This matters.

Yorktown Victory Monument, 1881-84, Yorktown, VA

One problem with the flacid modern notion of Art! is that it tries to jam too many different agendas and types of production into one meaningless category.

The reality is that a commemoration...

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Virgin with Angels, 1881, oil on canvas, Forest Lawn Museum

... a work of beauty...

Judy Chicago, Menstruation Bathroom, 1972, installation with toilet, garbage can, used tampons, in Womanhouse, a converted LA house

... and a retard dribbling bodily fluids are fundamentally different artifacts.

Different to the point that any umbrella more specific than "visual works" or "imagery" collapses into meaninglessness.

This is why we fell back on our old Greek terms of techne, episteme, and phronesis - refined technical skill in the service of higher truth to bring beauty and/or wisdom into the world. Click for the post.

Here's the summary and graphic from the linked post

Techne is skilled craft. It’s material, and follows culturally-specific customs.

Episteme refers to higher principles in the abstract - the metaphysical ideals that don’t exist materially.

Phronesis is the coming together of the two - techne guided by episteme. “Art” can be distinguished from "craft" or "skilled labor" as phronesis. It is techne whose main purpose is to communicate something about episteme in material terms, whereas craft would be aesthetic decoration on something functional.

The mistake to define art as either the making or the ideals - it is the coming together of the two.

And another graphic from the post, showing how neatly our Greek-derived art terms map onto the ontological levels we traced out earlier. Episteme is the Greek version of what the West would call ultimate reality or Truth and understood in a Christian context. Techne is material technique and dependent on culture and circumstances.

This means phronesis - art - can be thought of as an abstract.

This means phronesis - art - can be thought of as an abstract.

Not all pictures meet this criteria, and things can be appealing and alluring without reaching for Truth. But if we are going to find a working definition or set of aspirational goals, this seems like an effective measure. One that excludes corruption and subversion out of the gate.

By this, we conclude:

That's satisfying. We need more of that.

One thing that Modern Art! did was redefine the practice as something negative and corrosive - "critique" rather than truth and or beauty. This is partly a consequence of modern relativism - the de-moralized materialist nonsense that masquaderes as modern "thought" can only survive in it's dank crannies by pretending that Truth is something that we can't steer towards. Because of this, it becomes recursive and self-consuming - with no external pole star, all it can do is spiral reductively until it nothing is left but a slime trail.

Opening Reception for Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art, Queens Museum, 2014

Think about it. A cloud of toxic, midwitted atavists standing in a self-stroking circle and pretending it means something other than a cultural bottoming out. Were it not for the clouds of globalist money and jacked institutions, they would be beyond ridiculous and beneath notice. They are beyond ridiculous. And there is no need to pay them any attention. Just spare a moment for the horrors witnessed by the poor dumpster out back.

While is can be sad to see the moldering carcasses of once-prestigious institutions, they are neither art nor creativity. That's just globalist fiction. Support what you like, and time will take care of this institutional sojourn into madness.

The advantage of phronesis as a basis of art is that it incorporates technical ability and higher values in a single creation. This obviously rules out modern trash, but is also clarifies things when applied historically. Returning to the Middle Ages, the art of the first millennium was almost entirely Christian in episteme. There are exceptions, but not enough to be statistically noteworthy.

Stefan Lochner, Madonna of the Rose Bower, 1440-1442, tempera and gold on oak, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

Moving into the second millennium, the aristocracy comes into their own, but it takes a few centuries to start to see significant patronage for what we might call secular subjects.

Where the change comes in first is around the edges - as secular clients support variations of Christian subjects with worldly and self-aggrandizing connotations. Like depicting Mary with the crown, robes and hairstyle of a Gothic noblewoman. The symbolism is purportedly Queen of Heaven, but the real effect is to conceptualize Christian holiness in terms of grasping materialist aristocratic avarice.

More on this in the next post.

For now, let's consider how techne is responsive to material conditions even when there is no dispute over the underlying episteme. Consider two really high-level artistic accomplishments of early post-Classical Europe - the illuminated manuscripts of the Irish monastaries and the mosaics in the great Roman churches. Both are examples of refined technical skill and standard religious values, but the messaging is very different.

Lindisfarne Gospels, fol.27r. Incipit to Matthew, 715-720 from the monastery at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland, British Library, London

The last post on the roots of the art of the West looked at the Irish manuscripts, so there isn't much need to go into detail here. The manuscript culture developed over several centuries from simple scribes' embellishment to masterpieces like the Lindisfarne Gospels or the famous unfinished Book of Kells. Eventually this culture was destroyed by intensifying Viking raids, but their works survive as testimony to their techne.

In incipit is the opening words of a book, turned into a label page.

The Irish manuscript painters were not professional artists in a modern sense, but so much of their day was taken up by writing and painting that they developed professional-type skill sets. But their work can be difficult to analyze because they were not meant for public consumption. The books would be used within their monastic community, but not circulated outside, and the general populace didn't have access. The fact that people all over the world - even non-Christians and non-Westerners - like them today is testimony to the artists' visions, but not relevant to their original purpose.

Lindisfarne Gospels, fol. 210v, cross-carpet page

What that purpose was is not exactly clear - some combination of pure praise for God's glory and perhaps a way to visualize the richness and wonder of creation.

It is easier to discuss where the inspiration came from. The Irish monks were combining their indigenous Celtic art forms with compatible Germanic influences plus some second-hand classical influence from the neighboring Anglo-Saxons in England. The result was a unique visual form that echoes from galleries to tattoo parlors around the world today.

Mammen-style axe, iron with silver inlay, 10th century, National Museum of Demnark, Copenhagen, and rendering of the pattern on the other side.

Viking art is is a version of the Germanic Animal Styles that were common with many of the post-Classical tribes. Because the Vikings retained their unique culture longer, more of it survived.

Elements can be found in the Irish monastic manuscripts, but with a major difference. The Animal Style avoids controlled patterns for wild, uncontrollable forms. It bursts and spreads over the surfaces with uncontained chaotic energy.

Lindisfarne Gospels detail

It isn't hard to see the Animal Style influence alongside the Celtic interlace and spirals in the medieval manuscripts. But the Irish variants discipline and contain the wild tangle to a overall structure. This seems symbolic of God's plan behind the apparent chaos of the world around us.

The Roman mosaics present us with a very different kind of artistic context and experience. They would have been seen by a lot more people, being prominently displayed in houses of worship attended by the public at large. The purpose here was to transform the interior into a visual experience worthy of the Incarnation and Resurrection commemorated within. It's an ironic truth that the great mysteries of the Christian faith are metaphysically world-changing, but aren't comparably spectacular to look at. Grand public Christian art is a sort of metaphor in that it tries to show you something that at least hints at the indescribable glory of salvation.

Apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana, Rome, 410-417 AD.

This spectacular mosaic was installed almost immediately after the Sack of Rome by Alaric and his Goths. It's been cut down from its original size by subsequent renovations, but the core of it survives to show the basic idea. The four beasts of the Tetramorph - old symbols of the four Evangelists are badly cropped.

The quality of the tile work is still clear in the subtle treatment of the faces of the figures. Mosaic was popular in ancient Rome, but it was the early Christian artists that elevated it to a fine art form.

It appears that the shimmering effect of the shiny tiles appealed to the supernaturalism of the new religion.

One of the things that makes art such an effective means of communication is the way that it can combine multiple messages in a single picture. It is easy for an artist to layer connotations and allusions through strategic details and the structure of the arrangement.

The great early Christian basilicas that were designed to accommodate the growing numbers of faithful. These were based on an Imperial building type associated with the emperor's authority. By using this as a template for church architecture, the message was sent out that the Church and the Imperium were essentially the same thing.

The treatment of Jesus as an enthroned imperial figure in golden robes defines the King of Heaven in terms of a worldly emperor. On the one hand it is using a familiar form to communicate Jesus' heavenly status. On the other, it plants the association between Christianity and political power that is alien to Jesus' charge to "render unto Caesar" that we saw in an earlier post.

Emperor Alexander of Byzantium (870–913), 10th century, mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

The notion of Imperial Church followed the emperors to Constantinople - after the fall of the Western Empire, there was no Roman emperor to LARP as God on earth. But the notion that the Church was an imperial hierarchy, just rooted in spiritual rather than earthly affairs - remains.

The mosaic and the monastic manuscript are both high quality, high value works of art that are thematically Christian but apply their techne to different interpretations of Christian episteme. Both assert the primacy of God and his redemptive sacrifice through Jesus, but in ways that reflect the ideologies of their respective contexts.

Lindisfarne Gospels, facsimile edition

The illuminations are contemplative - something to meditate on intimately when reading the text and considering the mysteries of the faith.

The mosaics are billboards - looking to characterize Christianity in politically-familiar terms to a bulk and often uneducated audience.

Now what happens when "secular" aristocracy is able to undertake comparable acts of patronage? If the Christian messaging is filtered through the subjective concerns of the client class, what happens when the message isn't Christian?

As with many aspects of European civilization, Charlemagne is the first to set up "secular" art production as part of his manuscript copying program. But centuries will have to pass before we start to see widespread aristocratic art production.

Mirror case with courtly love scenes. Paris, first third of the 14th century, carved ivory, Louvre Museum

Like the institutionalized moral bankruptcy of the "courtly love" tradition - like a response to the equally perverse aristocratic culture of arranged political marriages. The normalization of adultrous affairs among parasitic do-nothing "nobles" is a distant forerunner of our own debauched and perverse "elites".

Looking into history makes it more and more apparent that the existence of a distinct parasite class is perhaps the largest single (human) driver of moral entropy and decay. But the stupid and ethically bankrupt find it "romantic". So there's that.

Eventually, a full-scale aristocratic court "society" grows up in parallel to the nations that support it, but is purely international in scope. And at this point, one of the main ingredients of what will gradually metastasize into globalism is in place. But before we go there, we have to consider a rise in artistic internationalism that precedes the "secular" aristocracy. That is, the emergence of a pan-European aesthetic within the structures of the Church. Because while it is true that the appearance of an imperial aristocracy creates the context for a hostile, internationalist culture within the nations of Europe, is isn't until the into the 14th century that we see it reflected significantly in art.

Boucicaut Master, Annunciation from a Parisian Book of Hours, 1415, ink, tempera, gold on vellum, Cleveland Museum of Art

The art that compliments this internationalist parasite culture is results from the growth of the Church as a pan-European body. Basically, the Church builds the international art world that the international aristocracy will eventually jack and turn into the forerunner of globalist Art!

It's just easy to miss the connection because the aesthetics of the medieval Church actually prioritize beauty,

This is a much longer and more complicated process than this simple summary makes it sound, and not something that can be dealt with effectively at the end of a post. So for now, what we will do is look at the emergence of the first true international art movement in Europe since ancient Rome in the so-called Romanesque period - how it comes into existence, the purposes for its reach, and how it points towards a much more sinister future than could have been obvious at the time.

The Romanesque is best known as an architectural phenomenon because that's what survives for the most part. The remaining evidence does suggest that the visual arts follow a similar universalizing pattern, but there is a lot less material to judge. So we will look the uniform building style first, then make a couple of observations about painting, statues, and the like that the evidence can support. The point isn't to provide a comprehensive overview of Romanesque art - that can be found in many sources. What we want to do is demonstrate the formation of an internationalist aesthetic that works at cross-purposes to distinct national cultures. Because this is what will prove most historically important.

St. Michael's Church, 820 - 822, Fulda

The Romanesque is difficult to date because there is no scholarly consensus when it first appears. It's characteristic heavy stonework is already visible in the massive architecture of the Carolingian Franks of the 8th century, like this. The main portions anyhow - The core was extended in the 11th century and the west tower added. The conical roof is 17th century.

Most historians place the origins of the Romanesque in the 11th century. That's good enough for us, because that's when all the main architectural characteristics are visible. The name is also confusing. When you read Romanesque, it is easy to assume it refers to a style based on the building types of ancient Rome. Something Classical or late Imperial. But it doesn't. The only things "Roman" about the Romanesque are the use of round, Roman-type arches and vaults, and the overall mass of the stone buildings.

Maria Laach Abbey, 1093-1177, Laacher See, near Andernach, Germany

This is a good example of a German Romanesque abbey church. The expanded west end is a typical Romanesque feature, but not universal. The round arches, small openings, and massive structural elements are signs of this style.

And the side view, showing the exaggerated west end. The technical term is a Westwork and they were most common in the Germanic world.

Church of St. Trophime, begun 12th century, Arles

The appearance of Romanesque buildings can be quite varied, but the basic features - small openings, round arches, and massive walls - are consistent.

The interior of mature Romanesque churches like St. Trophime are characterized by their heavy vaulted interiors. Specifically barrel vaults - half cylinders - like the ones seen here.

The overall proportions are quite tall - comparable at times to the soaring Gothic churches that come later. But the heavy stone and small openings create a totally different feel.

Secular buildings like this oldest part of the Tower of London don't have the same high vaults as the Romanesque churches, but the round arches, small openings, and massive walls are similar.

The White Tower of the Tower London may have been started in 1078 but this is uncertain. It was completed by 1100.

The spread of the Romanesque is usually credited to the growth of the centralized Church, but the reality is a bit different. That's because - as a surprise to no one - "religious authority" and "secular authority" weren't really separate. More intertwined by familial, political, and economic interests into mutually self-serving elite without concern for the masses that supported them.

There's a really good parallel today with the retards that believe state and corporate power are somehow opposed.

Those too stupid for the cartoon might find a slightly more dialectical meme does the trick.

The point is, then as now, the elites corrupt and co-opt supposedly opposite centers of social power into an incestuous web of veiled collusion. The names and claims change, but the result is practically identical.

The spread of the Romanesque across Christendom for both religious and secular architecture gives this unholy fusion a visual form. And nothing captures the fusion of noble and ecclesiastic power at the dawn of the Romanesque then the rise of the Congregation of Cluny.

Cluny was an offshoot/reform of the old Order of St. Benedict - the preeminent form of early Medieval monasticism. The term order is a bit of a misnomer, since the Benedictines were a collection of independent foundations rather than a single unified hierarchy. The movement began when St. Benedict of Nursia founded his first monastery at Subiaco in Italy in around 529. From the outset, he conceived each house as autonomous communities of monks. The early Benedictines supported themselves through farming and other labor around their houses, and devoted the rest of their time to prayer and scholarship. In time, they became the primary centers of manuscript production in the West.

The Plan of Saint Gall, 820–830, Abbey of St. Gall (Stiftsbibliothek Sankt Gallen) Ms. 1092, Reichenau, Switzerland

Ideal (unbuilt) plan for a Benedictine monastic compound, with churches, housing for monks, workers, and guests, stables, kitchens, workshops, brewery, and medical facilities. This shows the original manuscript, a clearer modern copy, and a 19th century recreation of what it would have looked like had it been built.

The San Gall Plan was an unbuilt ideal, but it captures the concept of the independent and self-sustaining Benedictine foundation.

Cluny Abbey was founded in the early 10th century under the Benedictine umbrella, but with a few major differences. The first was the governing structure - rather than independent houses following the same Rule, it became the center of a highly centralized ruling structure with tight control over all the Cluniac foundations that followed. Subsidiary houses were technically priories rather than independent abbeys - a radical departure from Benedict's original vision. As Cluny's influence spread, it drove a transformation of western monasticism, from self-sufficient units to an elite pan-European hierarchy. According to one site, the order peaked at 1,184 houses in the 12th century.

Consider the foundation of the original Cluny:

William of Aquitaine addressing two monks of Cluny, historiated initial, from the Miscellanea secundum usum Ordinis Cluniacensis, late 12th-early 13th century, Bibliotheque National de France, MS 17716 f.85r., Paris

The first house was established in 910 by an aristocrat - William I, Duke of Aquitaine - on the site of his hunting lodge. Somehow he could set up a monastery, name an abbot and declare him subject only to the pope - completely independent from kay authority, but the ecclesiastic hierarchy. And even the pope couldn't dissolve Cluny or take its lands without the permission of the monks. It's unclear where this power came from - it likely didn't exist officially. But the papacy could see the value in such a body, and actively supported and promoted Cluniac growth and influence. The result was an organization of unprecedented independence.

When a secular aristocrat is founding monastic houses and determining their legal relation to the Church, you can see the absurdity of the notion that "Church" and "State" are separate entities. And the papal encouragement of this intrusion further supports the image of two hands and the same body.

Just like global corporations and big government today. An illusion of difference that might have been convincing in the 10th century, but you'd have to be pretty ignorant and/or dim to still fall for today.

The original house was endowed with the resources for self-sufficiency with agricultural lands, vinyards, timber, water, mills, and serfs to work it all. As the order spread, it grew in wealth and influence, and the abbots became significant figures in European politics. The monks themselves gave up the Benedictine ideal of physical labor and self-sufficiency and instead focused on the liturgy - religious observence and prayer - as their main work.

Monks Singing, around 1420, tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, Getty MS. 24, f.3v.

This was very lucrative. It was widely believed in the early Middle Ages that monks' collective prayers had a tremendous impact on one's hopes for salvation, and the nobility competed with each other for monastic focus on their souls [click for a link]. This took the form of lavish gifts and benefices, and since individual members of the order couldn't own personal property, Cluny itself became ridiculously flush. According to Infogalactic, it became the grandest, most prestigious and best-endowed monastic institution in Europe. The monks could hire workers to do their traditional labor in lived in relative luxury with fine foods, gold and silver furnishings and silk vestments.

With their focus on liturgical activity and immense wealth, Cluny became a hub of art and architecture. Their leadership was closely connected with papal and aristocratic elites, and their vast centralized structure spread their ideas across Europe. Architecturally, the first foundation was the site of three successive Cluny Abbeys - each larger and more lavish than the previous. These are known as Cluny I, II and III to distinguish them.

Plan of the Cluny complex with the relative size and positions of the three Abbeys. The difference between Cluny I and III is a good measure of the growth of the order in size and power.

Joan Evans, The Romanesque Architecture of the Order of Cluny, originally published in 1938, reprinted 2011, Cambridge University Press

Cluny II was built around 955–981, and is credited with introducing the stone vaulting that would be characteristic of Romanesque churches to Burgundy. Today, Burgundy was a French province, but in the Middle Ages, it was a major center of art, economic, and cultural production.

This canonical old work of architecture history laid out the influence of Cluny on the spread of the Romanesque in Europe.

Recreation of Cluny II. It was a basic early Romanesque-type basilica with heavy stonework, small openings and massive barrel vaults.

The tall square crossing tower created an impressive profile.

Cluny III was started in 1088 and was a truly colossal project - the largest church in the world until the construction of Michelangelo's New St. Peter's in the Renaissance. Little remains of it today, but what is known indicates similar cutting-edge engineering. The heavy Romanesque groin and barrel vaults were replaced with lighter rib vaults - an important predecessor of the more advanced Gothic architecture to come.

Model and 19th century drawing recreating the Cluny complex and Cluny III.

The Abbey was even bigger than St. Peter's and the other Constantinian basilicas of Rome.

And a diagram of the complex with labels:

Consecration of Cluny III by Pope Urban II, 12th century manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale de France,

The connection with the ecclesiastical elites is clear in this manuscript by Abbot Odo of Cluny with a picture of the pope consecrating the newest Abbey.

But it was short-lived. Cluny went into decline even as its magnificent mother church was rising. The cost of the building strained the order's considerable treasury while mismanagement of resources and changes in European society put pressure on revenues. Within the monastic sphere, the opulence and luxury of the Cluniac foundations was off-putting to more austere and reform-minded orders like the Cistercians.

Giotto, St. Francis Preaching before Honorius III, 1297-1300, fresco, Upper Church, San Francesco, Assisi

Outside the monastic world, Europe was urbanizing in the 13th century, and the new mendicant orders - the Fransciscans and Dominicans being the most prominent - weren't bound to monastic foundations and were better positioned to meet the spiritual needs of this new world.

And the rising national monarchies in England, France, Burgundy, and elsewhere were less supportive of a powerful pan-national body that the earlier aristocracy.

Cluny was eventually suppressed in 1790 by the perverse atavists of the French Revolution and Cluny III demolished in 1810. Today only one of the eight great towers exists to give a sense of the scale.

The Cluny library - one of Europe's greatest - had already been damaged when mindless Huguenot savages sacked the Abbey in 1562. At least they earned their reward on St. Valentine's Day. Many more manuscripts were destroyed during the dispursal of the order's resources in 1790. Although Cluny is largely forgotten today, it was a pivotal development in the move to centralizing the arts and the integrated elites in Medieval Europe. Consider that the papal election of Pope Callixtus II was actually held at Cluny in 1119. And that Cluny was a major supporter in the idea that kings should be venerated as supporters of the Church. There was no comparable body at this early date so instrumental in knitting sacred and secular power together in a single notion of the elite. In the world of art, the style of this new socio-religious configuration was the Romanesque.

That's enough for now. The next arts of the West post will look at the visual arts of the Romanesque, the transition to the Gothic, and what this can tell us as nationalists pushing back against the manifest evil of globalism in the present. Until then, some foreshadowing:

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete