Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

Time to pick back up with the art and culture of the West.

François Gérard, Ossian on the Bank of the Lora, Invoking the Gods to the Strains of a Harp, around 1800, oil on canvas, Kunsthalle Hamburg

The Ossian craze of the later 18th and early 19th century was a reaction to the northern European desire for ancient heroes from their own cultures. Stylistically this anticipates Romanticism. Ossian turned out to be a fraud, but the strength of national identity is real.

The last few posts have been an occult image three-parter on the symbolism and history of the obelisk. Occult and regular posts are kept separate, but this was a bit of a journey from the ancient world into modern times. That is, same path the Band has been following, but a look at one symbol instead of broad patterns. It's relevant because it is an example of the way that the "roots" of the West that we have been tracing work empirically.

The obelisk is an ancient symbol that was taken up by the Romans, then revived again and again after the Middle Ages. Each time, the circumstances are different, so the specific message changes. But the basic associations that the specifics adapt stay consistent. Not changeless - they modify slowly over time because they can pick up new associations through reuse. It's a consistent frame of reference that evolves and shifts as the situation changes.

The roots of the West are like that, only on a macro scale.

The Christian and Classical heritages are a civilization-sized obelisk that shifts and evolves with the passing of time. It's easier to see if you think of "Christian and Classical heritages" as a single symbol representing a basket of ideas. This floats down the timestream changing and evolving as the circumstances do - never staying quite the same but tracing out patterns - frames of reference - that are visible in the historical record. The nations are the changing circumstances.

Paul Delaroche, Hémicycle des Beaux-arts, 1836-1841, oil on wax, École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris

There is too much to recap without turning this into a recap post. But the journey followed the rise of secular transcendence and Progress! as fake faiths that underscore the vanity of the modern world. We took the New York Armory Show of 1913 - the arrival of Modern Art in America according to the standard histories - as a point of departure for a deeper look into what the arts of the West actually are. And 1913 was a huge year for globalism.

Lorenzo Montezemolo Marin County, from Mt. Tamalpais, 2016, long-exposure photograph

One of the biggest reasons that the Band has embarked on this winding historical path is because of the human tendency for recency bias - overvaluing one's personal experience and ignoring the larger patterns that make it possible to understand what is happening. It is easy to bleat that Postmodern culture is a cesspool, but there is no way to understand how it happened - and most importantly, how to get out of it - with knowing where it came from.

Postmodernism is a mutation of Modernism - an "antithesis" of Modern aesthetics that didn't change any of the fake institutional structures that Modernism imposed on culture. Postmodern aesthetics are based on the idea that the subjective, socially-constructed, symbolically-mediated human experience of reality is all there is. It's a form of inverted mysticism where the chains of signs and symbols point endlessly to each other. There is no meaningful if imperfectly perceived reality that is outside or prior to us. Discourse is the sum total of all these recursive sign systems, and therefore replaces ultimate reality at the top of Flatland "ontology". Human-created discourse. Secular transcendence if transcendence was a void.

Something that nonsensical doesn't come from nowhere.

Sandy Skoglund, Revenge of the Goldfish, 1981, photograph of an installation

A work - in the wrestling as well as artwork sense - like this demonstrates that "reality" as we know it is meaningless. The humans are colored differently from the background - they are "real" in a way reality isn't. The fish make an attention-grabbing contrast and the absurdity supposedly shows how artificial what we take as existence is.

The Postmoderns were right in identifying discourse as an incoherent empty construct, but became inverted Satanic liars when they claimed that that means there is nothing beyond human subjectivity. The old luciferian will and desire, but with an infinite abyss in the place of any idol. The correct question was to ask how the hollow discourse that they were deconstructing came to be taken for reality in the first place. Who decided to replace ontology and epistemology with self-evidently fake secular transcendence?

That's Modernism.

Jean Francois Lamoureux and Jean-Louis Marin, FIDAK (Foire Internationale de Dakar), 1974, Dakar, Senegal

Henri Chomette and Roland Depret, Hotel Independence, 1973–1978, Dakar, Senegal

Brutalist Modern "essences" of form and material unironically presented under the heading "Architecture of Independence". How do featureless globalist geometric slabs designed by French architects mark the Senegalese freedom from an alien imperial overlord?

Modernist discourse is a secular transcendence because it pretends man-made "rules" are universal truths. The Band has posted a lot on this nonsense. Here's one that focuses on the "essence" of modern architecture.

Countering the pure self-indulgence of Postmodernism with truth-facing cultures that actually express organic national identities means understanding how one-world globalists jacked those cultures in the first place. Why, for example, is "American art" defined by museums, critics, schools, and other bodies that despise American culture and people? Why do people think of pretentious atavists and shrill harpies clamped onto the public teat when someone mentions "art school"? How does something that expressed the identities of peoples for as long as there have been peoples become a weapon for soulless elites to erase cultural identity all together? Among other things, Modernism took the endless resources of modern economics and created a de-moralized web of globalist top-down institutions in place of organic cultural formation.

Readers are well aware that this is all connected. Economic modernism created a new globalist financial elite that took the quiet treason of the old aristocrats to a new level. The appeal of 1913 and the Armory show is that this is just the artistic side of that annus globalistis. The same year brought income tax and the Federal Reserve, with the lies and atrocities of World War One to follow.

When things cluster like that, it makes it easier to spot the connections between the cultural and socio-economic elites - the centralized systems of globalism and cultural degradation are being set up at the same time. When big events converge like this, it's impossible to miss.

So to counter Postmodernism with a real art of the West, we have to understand what is real. And that means looking for what the fake institutional webs of Modernism replaced. And that brought us back to the beginnings.

The inescapable problem for all historians is that the past is out of reach. It is impossible to ever fully understand how people in different times and places thought. The Postmodernists were right on this one - our perception and understanding of the world is subjective. It is produced through our experiences and cognitive processes. But history has a further problem because we can't experience it - even imperfectly and subjectively - directly. There's no obvious equivalent to how clear language suddenly becomes when you offer a Postmodernist a hundred bucks. No matter how honestly we try to face reality, we are limited to what ever scanty things have survived as the historical record.

Sorginetxe Dolmen, around 2500 BC, Agurain/Salvatierra, Spain

Entire cultures have disappeared without a trace - lost to us completely. Prehistoric peoples leave no written record at all, and even the ancient cultures we do know are reconstructed from trace evidence.

Daniel Ridgway Knight, Coffee in the Garden, oil on canvas, 66.9 x 80.9 cm, oil on canvas, private collection

But more recent history also has things that are out of reach. Speech patterns, popular assumptions - the "feel" of life - can't be captured in pictures and documents. If all experience is subjectively filtered, history is second or third hand.

This reality puts certain conditions on our journey into the past. Since specifics are vague, we have to stay general. Which works best for blog posts anyhow. And if the goal is to counter Postmodern globalism with real cultural expression, the answer isn't to reenact the past - it is to understand what it was that enabled organic creativity in the past and apply that to the present and future. That means what we can know and how we can know it - where understanding and expression come from in a general way. Bringing this historical look at the roots of Western culture together with the older posts on epistemology and ontology has stretched things, but also let us flesh out some earlier observations.

Adolph Tidemand, Bridal Procession on the Hardangerfjord, 1848, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Norway

And a close-up.

Note the cultural homogeneity and personal familiarity of this village. It is a Romantic idealization of the past and the technical skill is distracting, but look past the rhetoric at the basic social organization. The enforced central control, promoted deviance, and orchestrated stresses at the heart of modern demoralization - and all the related public health, addiction, and mental health degradations - are absent. And a stave church at the center - a national cultural expression of Western Christianity. Ironic that in the language of the f@#kin' love science retards, this is how people evolved. It's natural.

See the full perversion of imposing globalist slabs on the Segenalese? Globalism destroys national cultures in different ways, depending on circumstances.

If healthy, organic, reality-facing cultures are to grow in the future, it is essential to understand what they are.

From the start, the Band has operated under the assumption that the West has three broad components - the Classical heritage, Christianity, and the nations of Europe. This is obvious historically. But any attempt to define the West in granular terms dissolves into endless ambiguities and exceptions. What about the Mozarabs?

San Cipriano, 10th century Mozarab church, Valladolid, Spain

Mozarabs were Spanish Christians who lived and functioned in Moorish Spain who built Christian churches in Muslim styles. They're mostly "Western" but with huge non-Western influence. It's endless. So any working definition that is historically accurate and succinct will have to be very broad. Where do we start?

The collapse and fall of the Western Roman Empire makes a good starting point. Better then trying to fix a date. Rome had imposed a centralized administrative and economic structure over most of Western Europe - at least superficially - and introduced Latin as a common language. The empire also imposed a degree of cultural homogeneity and elite migration in the subject nations. This was radical in Europe, which didn't have a prior history of ancient empires or refined literary and artistic cultures like the Eastern Provinces.

Roman Theatre of Orange, 1st century AD, Orange, France

Rome was "civilization" - when it withdrew, it isn't an exaggeration to say European culture entered a new phase. Historically, this is the environment that develops into the modern West. It is possible to trace the winding path directly, through all the twists and ambiguities that make precise definitions wordy.

What are the general traits that run through this historical stew? The development of strong national cultures in relatively close geographical proximity. Christianity took different forms in different nations but had spread to every corner of Europe by the high Middle Ages. And the image of Roman power gave all of them access to this store of ideas to use in their own ways. Beyond that it starts getting blurry. But what was so fascinating was to see how this historical observation fit seamlessly with what we can know ontologically.

When we limit the West to a historical observation, it isn't obvious how the broad traits fit together. But when we think of them in terms of how we can know, each falls into a level of the epistemological hierarchy. Click for a long post.

Jules Claude Ziegler, 1835-1838, History of Christianity, La Madeleine, Paris

Christianity offered a coherent notion of ultimate reality that accounted for the limits of human understanding and the existence of evil in an uncertain world. But it didn't come with the philosophical structures to channel that into abstract social and legal principles.

Raphael, School of Athens, 1509-11, fresco, Vatican Museums

Classical philosophy showed the logical necessity of ultimate reality and the impossibility of discerning that directly. Since God was beyond positive comment, it turned to various forms of mysticism and the occult to make the leap from logical abstraction to absolute transcendence.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Apotheosis of Homer, 1827, oil on canvas, Louvre Museum

The seamlessness is almost breathtaking. And noting that isn't vanity - the Band didn't make any of this up. It is observation that comes directly from looking at history while asking what and how we can know. But if we are thinking about culture that is organic and reality-facing, this is a great starting point.

General doesn't mean careless, so a few things need to be cleared up. The last post raised the relationship between the arts and culture - art isn't a culture but it is an expression of it. You can see what they saw, and what they showed each other. We're obviously dependent on what remnants happened to survive and art is always rhetorical and ideological, but it's something. If nothing else, the rhetoric and ideology that they promoted.

Samaritan Woman at the Well, 200-250 AD, fresco, Catacombs of Praetextatus, Rome

For example - how the early Roman Christians visualized their new religion.

Bringing us to the next thing to clarify. We used Roman Christians to illustrate the adaptation of Christian metaphysics in a new material-level culture, raising the difference between culture and nation. The two aren't the same. The Band wrote a post on the differences between nation, state and empire - any one of these can have a culture. Here's the OED:

A culture is the shared ideas, assumptions, folkways, arts, etc. of a group of people. Any collective can develop aspects of a culture, but we are using it in the sense of the largely unconscious deep shared identity that comes from generations of life together. The OED tells us that the word itself derived from cultivating land, so the idea of being raised or growing together is implicit. Since nation is likewise based on kinship - extend family to tribe to nation - and derives from the word for "birth", there is a natural connection between nation and culture. But they're not the same thing, and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

Steve Hanks, A World for our Children, watercolor

There is an element of knowing it when you see it to organic culture. There is a health and stability from alignment with logos and empirical reality that is perceptible. For fantasy fans, the perception of health in Stephen Donaldson's Chronicles of Thomas Covenant illustrates it. As an aside, Donaldson is surprisingly insightful and may be the subject of a post at some point.

The Apotheosis of Lincoln, photograph Albumen silver print, 1865, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY

Fake, mawkish, top-down "cultures" are just as transparent. Donaldson's description of things stinking of wrongness is an apt, if strong example. The iconography is Christian and classical - classical apotheosis into a heaven of Christian-looking angels. The laurel crown was a classical sign of triumph used for Christian martyrs. But there are no overt Christian symbols.

Lincoln as secular "martyr" wanted viewers to associate a dead politician with religious sentiment. But there is nothing connecting this to real lived experience, Just the fake and subversive metaphsics of secular transcendence masquerading as "national" culture.

This is the state.

Culture is fractal - national cultures subdivide into regional or local ones and fall into larger ones like the West. Since the Band is looking at the formation of the European nations, the main focus is on the national level. It wasn't possible to look the catacomb artists in terms of nationality - the information just isn't there - so we were limited to what cultural tendencies we could see. A distinction between a Roman image-based culture with the more iconoclastic world of the Old Testament. Now we are looking for are signs of distinct national cultures rather than just visible trends in a polyglot empire.

There are similar problems with pre-Roman Europe.

Demographic map of Iron Age Europe showing the principle known cultures and movements of people.

There is just very little information on life in Iron Age Europe to go by. The peoples had no written language or stone architecture, so there are no records, monuments, or buildings to tell about them. Their climate wasn't suited to preserving artifacts, so archaeological data is limited to things that don't decay easily.

Reconstruction of an Upper Iron Age farmstead of 300-100 BC, Open-Air Archaeological Museum Havranok, Liptovska Mara, Slovakia

The dominant culture in Europe before the Roman were the Celts. These were a wide-ranging people that pushed as far as Turkey and were eventually subjugated by Caesar. But they didn't build stone cities like Greece and Rome

Witham Shield, La Tène Iron Age culture, bronze, 400 - 300 BC

The Celtic art we do have looks very different from Greece and Rome. Instead of people, the designs are abstract. Some elements are derived from the Greeks, but the spiraling curling patterns are pure Celtic. These forms are still popular, if not understood at all.

Dying Gaul, 1st century BC copy of 3rd or 2nd century BC Greek original, marble, Capitoline Museums, Rome

There are Classical accounts of encountering these "barbarians" but come relatively late and aren't really impartial sociological studies. This was one of several Celtic soldiers produced in the Hellenistic kingdom of Pergamon. The Pergamese had dealings with Gallican Celts and fought them several times.

Pfalzfelder Säule, 4th/5th century BC, Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, Germany

What Celtic sculpture we do have shows a totally different type of figure - a completely different aesthetic over all. But there is no way to know what this figure meant.

All we have then are the limited accounts in the classical record and what remains for the archaeologists, "New Age" simpletons aside. More on that in a moment.

Galician Celtic Stele for Apana, likely an aristocrat of the Supertamáricos tribe, 2nd century AD, Museo Histórico Provincial de Lugo

There were Celts who became literate, but they wrote in Latin or Greek, depending on where they were. This monument shows the family in an Eastern Roman style with a Latin inscription. Their viewpoint is already "Romanized" to an extent.

Since we can't get at the culture, we really can't say much about the religion. Roman accounts speak of horrible rituals involving human sacrifice, but it is difficult to confirm this or draw conclusions beyond pointing out the social benefits of Christianization. Hard information is so scarce that scholars can't even agree on the nature of the Celtic "gods" - whether they were abstract natural forces, animistic nature spirits, deities in the Greco-Roman sense, or something else.

Taranis-Jupiter with Wheel and Thunderbolt, undated bronze from Roman Gaul, National Archaeological Museum, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Celtic gods blended with Roman ones in the freewheeling religious environment of the later empire. Was Taranis a Jupiter-like sky god, or something different that merged with Jupiter into a syncretic form? Likely the latter, but there is no way to be sure.

Of course, that hasn't stopped any number of wiccan pagan "folkish" LARPing morons from doing a great disservice to Celtic culture. These sorry solipsists use the lack of historical information as an opportunity to project fantasy worlds where they get to be special. All kinds of pop occult, New Age, and goddess nonsense can be pasted onto Celtic-themed knot designs as a way to separate the more impressionable victims of modern alienation from their money and self-respect.

Like this inanity. Nothing about this is simple. It's literally impossible, and as a metaphor it raises huge philosophical questions. Readers of the occult posts are familiar with the spray of symbols and the spray of charlatans. It's important to remember when considering Celtic-flavored mysto-babble that there are no contemporary historical records for their beliefs at all. Biased Romans and 19th-century transcriptions of folklore are better than nothing, but hardly a mind-meld with a druid.

It is completely made up. Which is why the metaphysics are less coherent than a middling Dungeons and Dragons campaign.

Stephen Reid, cover to Eleanor Hull's The Boys' Cuchulain, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell and Co., 1904

It's mildly amusing that the interlace patterns that modern Celtic art is famous for isn't ancient Celtic. Abstract interlace and the plants and animal heads came from external influences - it's a cross between ancient Mediterranean and Germanic decorative patterns. That is, post-Roman and post-Christian.

This might be awkward if LARPers thought.

Schwarzenbach Bowl, about 420 BC, Historisches Museum Bern

Early Celtic design is made of flowing abstract patterns derived from palmettes and lotus motifs from the ancient Mediterranean world.

Anthemion (lotus and palmette), from the Erechtheion, 421-406 BC, Athens

Palmette from the top of a grave stele, around 480 BC, Archaeological Museum of Paros

Lyre-form anthemion, 470-460 BC, Archaeological Collection of Amorgos

The Greek anthemion lotus and palmette motifs likely derived from the ancient Middle East. But they were generally decorative embellishments. The Celts make them the center of their art - splitting, dividing and embellishing.

Gold-plated bronze disc from Auvers-sur-Oise, early 4th century BC, Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris

The material records are scarce, but there are enough pieces to see the development. The palmette and lotus roots are still visible, but the forms have evolved into a more sprawling, complicated pattern.

The Desborough Mirror, 50 BC - 50 AD, Bronze, British Museum

Relatively late bronze mirror with a mature design. It is a complex pattern with smooth spirals over a basket-weave texture. It's developed a long way from the Mediterranean palmette, but there is still no "Celtic interlace".

So where does it come from? This glance at the history is not an attempt to claim modern symbols of Celtic identity are somehow "not really Celtic". They are. National cultures change gradually over time - trying to freeze a single moment is conscious revivalism, not organic society. Isolating a cultural moment in history is like a snapshot of a nation - where they were at a particular moment, but not what they are in perpetuity. It's the continuous connection of a people with an evolving culture that lets us start to identify nations.

Modern Celtic interlace is based on early Medieval interlace that was invented by Celtic people in Celtic regions. The symbols are Celtic.

But they aren't pagan.

Ahenny High Crosses, North Cross, 8th-9th centuries

The interlace was a product of the Insular period of Celtic art. It first appeared in manuscripts, then on the famous Celtic high crosses like the ones at Ahenny.

And a nice look at the interlace.

Other abstract designs appear that are older. The spirals and square patterns go back to pre-Christian times. But the interlace is new.

If we think of the life of symbols, it is a historic marker of Celtic identity. Just one that connects to the Western Christian aspect of their national history.

Irish Celtic and Christian looks like two of our three roots...

Making this sort of spray of symbols unintentionally ironic.

But it does reveal something beyond the historical confusion of the LARPer. Notice how the interlace makes a much more tangled and chaotic knot than the evenly-distributed version on the Ahenny cross. This is another outside influence, and like the Greeks and Romans, not Celtic at all.

Muiredach's High Cross, 10th or possibly 9th century, Monasterboice, County Louth, Ireland

Look forward in time a couple of centuries - cultures take time to change and things can become more obvious in hindsight. This is one of the finest of the Irish high crosses, and rightly considered a masterpiece of Insular Celtic art. But not the lack of interlace. It's mostly panels with figures and scenes.

The contrast is clear when you look at the smaller cross on the left. This one has a lot of interlace, but even it has a figure at the center.

You can see some of it around the Crucifixion on the other side.

Where are the figures coming from? The don't resemble the kind of figures that were made by the pre-Roman Celts.

Easby Cross, 800–820, Anglo-Saxon sandstone standing cross from North Yorkshire, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

But they do look a lot like the ones on the Anglo-Saxon high crosses found in England.

Figures derived - somewhat loosely - from the Romans.

That is, the Classical tradition.

The third pillar.

We can see that the culture that made these crosses - Celtic or Anglo-Saxon - is of the West. It's just that the Classical path up here is pretty tenuous, and needs a look.

Modern Celtic patterns have a large Anglo-Saxon / Germanic component. You can see it in the complex knots and intertwined beasts in the Easby Cross. There's clearly come cross-pollination or other form of artistic exchange between the neighboring nations. The problem is that you can see it in the art, but the history isn't there to really understand how the exchanges played out.

On the other hand, the big patterns reveal a lot.

Ireland and Scotland were the two westernmost parts of Europe that were never conquered by Rome. There is no equivalent to Roman Britain to plant seeds of direct Classical influence on the development of the regional culture.

St. Patrick Baptizing the pagan King Leary, 1911, stained glass window, Saint Patrick Catholic Church, Columbus, Ohio

St. Patrick is the figure most connected to the establishment of Christianity in Ireland. The exact details of his history is uncertain but he was active in the 5th century. He may not have been the first Christian on the island, but he was instrumental in its spread.

So Ireland became Christian without ever being Roman. This alone is enough to establish a very different national culture from neighboring England. The Classical comes through intermediary channels. And to see how this happens, we have to look into the landscape of Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The collapse of the Western Empire was a period of social decline and military defeat but the real transformation in the West was demographic. When the Romans conquered Europe, they led with armies. Some settlement followed, but the Roman population was insufficient to radically change the demographics. So Gaul or Britannia remained more or less Celtic under Roman administration. The introduction of Roman infrastructure, economics, written and artistic cultures, technologies, and other trappings of civilization changed the national cultures without changing the tribal or "national" identity. The Germanic or "barbarian" invasions that collapsed the Western Empire were very different.

The Migration Period that preceded the imperial collapse were movements of entire peoples. Here's a German map with main tribes translated that shows the the migration patterns.

The career of Emperor Marjorian is illustrative of how much things were changed. He campaigned successfully to restore the Western Empire for several years before being betrayed by traitors and assassinated by the treacherous general Ricimer. Apparently his reforms upset the aristocracy.

There are two interesting lessons. Even in the most extreme civilizational crisis, elites will actively undermine the polity for their own short-term interests. The take-home is that there are no circumstances where the aristocracy can be counted on to prioritize national survival.

The other is what Marjorian was campaigning against. Note the forming Germanic nations. These didn't exist when Caesar invaded Gaul. The people were different.

These barbarian migrants were made up of different tribes that moved into the relatively sparsely populated parts along the northeastern border then spread west and south. There were attempts to integrate these people into Roman service - mainly military and administrative, but the empire had become so corrupt and degenerate that there really was no practical example of Romanitas for the new Romans to aspire to, even if they had wanted to. It looks like a decadent, spent society being swept away by a vibrant, confident new people. But that oversimplifies.

The Celtic inhabitants were displaced to an extent, but more subjugated and assimilated. The demographics of the modern French reveal these hybrid origins. It looks like the national cultures of Europe reflect the preponderance of the Germanic-Celtic admixture, but this is too much of a generalization to be useful.

Historically, the Germanic tribes present many of the same problems as the Celts. They didn't leave records, monuments, or stone ruins to tell us about their origins and very little is known about the details of their early culture. They appear to have been semi-nomadic slash and burn farmers under pressure from the movements of peoples further east. What is known is that they brought a tribal social organization and dark pagan belief system that resembled the pre-Roman Celts in some ways, but was distinct.

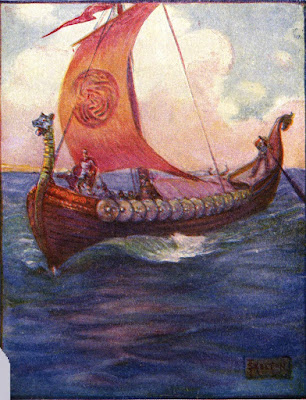

J. R. Skelton, Beowulf sailing to Daneland, from Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall's Stories of Beowulf, London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1908

Roman Britain was largely overrun by the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, who were close enough culturally to fuse over time into a single Anglo-Saxon culture. But also like the Romans, this didn't encompass Ireland or Scotland. So what was already a proto-national distinction strengthens.

Beowulf is the great national epic of the Anglo-Saxons, written between the 8th and 11th centuries.

The easiest way to try and see this period of upheaval and change is to look at the art of the time. The relationship between Germanic and Celtic art is like their cultures - different, but more structurally compatible with each other that either is with the Classical. Which is why they coalesce into hybrids, depending on the regional demographics. The picture is blurry, but we can sort of see national cultures forming.

Shoulder clasp (closed) from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial 1, 6th-early 7th century England. British Museum

The Sutton Hoo burials are a trove of Anglo-Saxon artifacts with a lot of pieces in very good condition. This clasp shows the common features of Germanic art in general. Abstract patterns with bright colors - especially polished gold and gems - were popular. Note the tangled forms around the edges of the central panels. They aren't that different in spirit from Celtic interlace, but are more knotted. And they include animal forms - there are abstract "heads" with eyes that appear to be biting the tangles.

Detail from Oseberg Ship, early 9th century, Vikingskipmuseet, Oslo

Here's an example of the gripping beast version of this Germanic tangle that appeared in Viking art. The Vikings were themselves tribal migrants of Germanic origin, but their remote location allowed them to develop a really distinct culture over time.

The Oseberg Ship Burial is a Viking version of the Sutton Hoo sites - a trove of artifacts in great condition. The early 9th century date is about 200 years younger.

Silver Anglo-Saxon ring, 775-850, found in the Thames at Chelsea, Victoria and Albert Museum

And an Anglo-Saxon version from around the same time as Oseberg. Tangled knots and abstract animals.

And back to Easby...

What happens is that the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon cultures of the British Isles remain distinct, but their arts borrow from each other. How this plays out varies from place to place - nations are distinct - but the inputs are the same - the West is a common identity.

Back to Ireland - if there is one art form more associated with the Insular culture of the early Middle Ages, it is the painted or illuminated manuscript.

Incipit to the Gospel of Matthew, folio 27r, "Liber generationis Iesu Christi filii David filii Abraham" (The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham), from The Lindisfarne Gospels, Cotton Nero D. IV, f.93v, around 700, British Library

A stunning mix of Celtic interlace and spirals and Germanic knots and tangles.

The Insular culture of Ireland developed in relative isolation - as the name suggests. The monasteries that spread over the countryside developed a unique book culture, with scribes creating more and more complex volumes. The Lindisfarne Gospels is a really nice example of their work. The Classical influence is at most implied - codex-type books were Classical innovation, and the preservation of ancient learning in this monastic copying was invaluable for the West. But there is really no Roman influence in the built culture. That looks like vernacular building types that probably go way back in history.

St. Kevin's Church, 12th century, Glendalough

Well-preserved example of medieval Irish architecture that probably resembles older buildings.

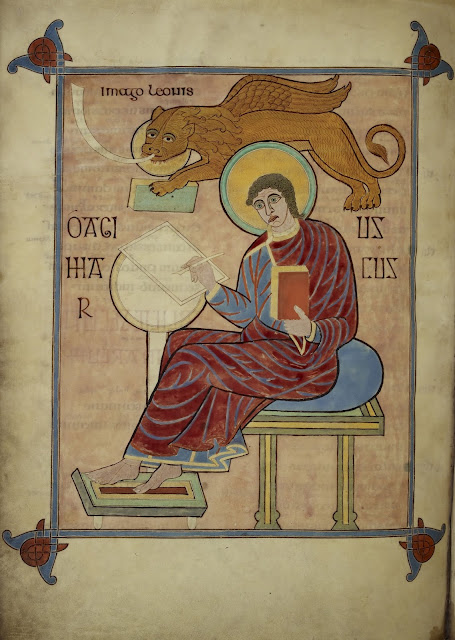

Now look at this page of St. Mark, with his winged lion symbol from the Lindisfarne Gospels:

The figure is much flatter and more like a schematic drawing than a realistic Classical figure but the inspiration is obviously Roman. The Classical influence comes through contact with Anglo-Saxon and first-hand experience with illuminated books from the ancient world.

For a contrast, take a look at The Book of Deer, a 10th century Scottish Gospel Book in Latin, Old Irish, and Scottish Gaelic. Scotland also preserved a Celtic culture, but without the active scholarship of the Irish monasteries. Rugged, unproductive terrain and warlike tribal clans maintained the independence to develop a national culture, but also isolated it from outside influences.

St. Luke, The Book of Deer, 10th century Gospel Book from Old Deer, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, Cambridge University Library MS Ii.6.32

The idea of leading off with an author portrait of Luke comes out of Classical book culture, but that's the limit of the Roman influence. This is pure Celtic, with even interlace and a strange, abstract figure with a huge head.

As for the Anglo-Saxons, their own art picks up Insular Celtic influences.

Evangelist Portrait of Matthew and text of the Gospel of Matthew starting at 1:18, Stockholm Codex Aureus, Folios 9v and 10r, from Southumbria, possibly Canterbury, mid 8th century

The spiral and tangle pattern is clear around the letters, but look at the author portrait:

Germanic art favors heavy solid forms. It made it easy to adopt certain things from Roman art. But note the delicate interlace in Matthew's throne. The Celtic / Insular influence adds a more intricate counterpoint to Anglo-Saxon art, but also to that of Western Europe in general.

The history of a people bound by a slowly evolving culture is a nation. And each national culture is a tapestry of many threads - Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Roman, or Viking heritage is only one of these. Romanization, migration, and time change cultures, but it is this shifting, flowing context that creates nations.

In the West, those cultures align with basic vertical ontology - Christianity as the metaphysical and moral foundation, the Classical heritage of abstract thought, and the material reality of the European nations.

Leading to a preliminary observation for anyone who might find themselves in the late stages of a degenerate empire. Note that there isn't a lot of "Classical influence" in the art of the Germanic tribes. Some aspects of it creep in through the arts, but it is more conceptual than anything reflected in the lifestyles and attitudes of the people.

All Saints' Church, 7th century with many later additions, Brixworth, England

The Anglo-Saxons and other Germanics learned the basics of stone architecture from the Romans. This side wall of this church is 7th century and shows the heavy stone construction and round Roman-style arches typical of the Anglo-Saxons.

But it doesn't look "Classical". No columns, ideal sculptures or Ionic orders. The technology is Classical, but the Culture is not. It's Anglo-Saxon, a proto-Western Christian nation with some conceptual Classical heritage.

The same could be said for the famous Book of Kells, greatest of the Insular manuscripts. The codex with an enthroned author portrait is a Classical artform, and the small figures echo Anglo-Saxon adaptations of Classical figure types, but nothing beyond that recalls Greece or Rome. The decoration and layout is Insular - Celtic spirals and interlace plus Germanic knotwork and animal forms.

The technology is Classical, but the Culture is not. It's Irish Celtic, a proto-Western Christian nation with some conceptual Classical heritage.

Christianity has a material component - the entire metaphysics of redemption is predicated on the divinity of Jesus as the Word made flesh, but this doesn't determine stylistic choices or lifestyle details. The Classical tradition offers pathways to apply abstract concepts to material life, but these don't require adopting ancient fashions. The upper tiers of the ontological hierarchy are abstract - the make themselves manifest in a material form. That material form is the culture of a people, and that coalesces into nations.

Change the nation and you change the culture.

Eagle symbol of John the Evangelist from the Book of Dimma, 8th century, folio 104v, Dublin, Trinity College, MS.A.IV.23

No comments:

Post a Comment