If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts have a menu page above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

Note on this post: As the Band has evolved, it has become more and more obvious that uncovering the lies and inversions blanketing the West is not sufficient - rebuilding a reality-facing culture means showcasing positive achievements as well. The very achievements hidden by the self-serving fake "truths" masquerading as modern reality. The problem is fundamental to the centralized authoritarian beast system that we live under and has corrupted reality-facing organic cultural development. Organic cultures are generative, evolving with circumstances and able to express values and identity through creations of truth and beauty. Lies are sterile - toxic fictions imposed by hollow, sociopathic human garbage with no capacity to build anything.

We see this in every aspect of pop culture today - no truth, no beauty, no reflection of real problems - just parasitic servants of the lie slowly throttling the host.

Blowing this up is essential - like tilling before planting - but the revival of Western culture and the free nations that make it up needs more. The inversion has been going on for so long and has become so ingrained that those trapped in its matrix have lost contact with the True, the Beautiful, and the Good.

Albert Gyorgy, Melancholy

Exorcising the cultural lies leaves them with emptiness. They have nothing to replace the fake poison that they've allowed to define their identities on every level.

This is deliberate.

Wrapping you in fake narratives is only one part of the globalist strategy - the other is suppressing the truthful alternatives. So that even if you realize that the "culture" entrapping you is a perverse, ugly inversion of reality, you have no where to go. Not even a benchmark to measure what is real or how badly you're being lied to. You've likely heard someone say that things seem "off" or wrong without being able to put their finger on it. Maybe even experienced the feeling yourself.

Vittorio Tessaro. Motherhood, 2001

So while we do have to go scorched earth on the lies, to be of lasting use, we also need to identify the Beautiful, the True, and the Good.

As best we can see it.

And this bring us back around to The Silmarillion.

We first tackled Tolkien as a way to reacquaint readers with Truth and Beauty - from a Western perspective in the first instance, but applicable to any reality-facing reader.

Trey Ratcliff, Hidden Temple in Bamboo at Night, 2009, Kyoto, Japan

Quick note - the Band has a number of non-Western readers because the beauty of Truth is that it is universal. Cultural norms differ, but that just means that someone outside of the West has to apply what we can know and how we can know it to their own material reality-level circumstances.

As omninationalists, we support the right of all nations to exist, unmolested, within the limits of reality.

The problem with our first crack at Tolkien was methodological - the Band's usual quick and broad approach of exploring origins and following tangents works better for deconstructing deep patterns than showcasing single works of art. The two Tolkien posts were packed with insights and observations, but struggled under the weight of their own sprawl. To the extent that they were objectively less effective than they could have been.

Leon Devenice, A New Beginning, oil on canvas

But coming up short is only a loss if you allow it to be - in this case, it was also a good opportunity to try something new.

That is, learn and adapt. Exactly the process that mass culture wants to replace with dependent protoplasm mindlessly twitching in fear and pleasure to centralized lies.

The Band is always looking for ways to further cultural growth that line up with what we can know and how we can know it, so why not add tighter and more coherent posts on real great artworks. A different take alongside the more speculative regular Band posts and occult images. It's a good idea, and potentially of value to readers that we don't appeal to now. We generally don't like to revisit our own posts because there is so much to cover and so little time in the week. But we just explained why revealing the True is essential - especially as lies are stripped away. If we want to remain on the offensive in this culture war, it would be irresponsible and self-indulgent to not take time to do what we can to make the desert bloom.

Kip Rasmussen, Thingol And Melian

So, a new category - focused looks at truth and beauty as we comprehend them. The two original sprawling posts will stay up. Here are the links: Part 1 - Logos in Flatland - Tolkien and the "Literature" of the West is the background-set-up, and Part 2 - The Light of the West - "Applicability" and The Silmarillion is a rambling trip through the book, If you're interested in a lot of background the literary modernism that Tolkien rejected and was rejected by, or how the ideas in this post developed, you can go back and read them. That way we can avoid tangents here and get to the point.

That is, J. R. R. Tolkien (click for Tolkien Society bio), the Band's choice for author of the 20th century - whatever that means - and someone largely outside of the official canon of Great Writers.

Tolkien as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers in 1916, aged 24

The reason for our high regard and the exclusion is the same - Tolkien wrote with a sincerity and a commitment to nation and beauty utterly opposed to the Modernist discourse. One could argue that he achieved his goal of producing a national mythology for England, or at least a national epic - a web of tales in different forms spanning the ages and anchored by the magnificent Lord of the Rings. Exactly the things that Modernism was dismissing as kitch, sentiment, and/or lowbrow.. It's one thing to have Mallory and Beowulf on some Western Civ. reading list, another to consider national myth in an age of relentless globalist ugliness.

Tolkien wrote The Silmarillion over the bulk of his lifetime but died before it was completed. The nearly-complete manuscript was edited and published posthumously in 1977 by his son Christopher with assistance from future fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay. Click for a link to the full text, but this one is worth buying.

The book is the backbone of Tolkien's imaginary world with ideas going back to his earliest writings in the nineteen-teens. He pitched it as a sequel to his hugely successful The Hobbit in the '30s. When it was rejected, he went on the write The Lord of the Rings, but continued working on the stories until his death.

It turned out to be successful after all.

Folio editions of Tolkien's Middle Earth books

Though not complete, The Silmarillion was far enough along to be considered one of his three Middle Earth books along with The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit - a surprisingly small output for an writer of Tolkien's fame. Then again, Tolkien was an unusual artist.

The published works draw on his real life's work - his Legendarium or body of imaginary histories and mythologies that make up a complete fictive world. This began in his earliest serious writings in the World War I era and continued until the end of his life. The importance of the Legendarium to him seems to one reason why he was such a reluctant author - committing the evolving mythology to a published canon cut off his ability to keep developing the stories. Knowledge of this source material also comes from his son Christopher who edited and published his father's copious notes in his 12-volume History of Middle Earth.

The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit take place near the end of this imaginary history - near the close of the Third of Tolkien's Three Ages. Though each was conceived as a stand-alone novel, it is clear from the depth of references to past events, legendary beings, snippets of songs and folklore that we are getting glimpses of a much deeper and larger world. This accounts for the hauntingly realistic depth that The Lord of the Rings in particular is famous for. The Silmarillion is different, focusing mainly on the First Age and laying out much of what was only hinted at in the other novels.

Christopher's work on the Legendarium also yielded several novels set in the First Age, expanding the world of The Silmarillion and returning his father to the bestseller lists decades after his passing. He found non-Middle Earth works as well, including a new translation of Beowulf.

The Silmarillion is not a single novel like The Lord of the Rings, but a collection of five individual narratives, each with its own subject matter and literary style. They relate to each other and tell a larger story, but are not presented as a single novel-like piece. What coherence they do have comes from their relationship to the Legendarium - taken together, the five stories present an overview of the entire history/mythology of Middle Earth distilled into a single volume. Tolkien doesn't posture as a visionary, but if he were, The Silmarillion would be the closest thing to his canonical scripture.

God creates Heaven and Earth, page from illuminated Bible, 1463, colored pen and ink drawing, Austrian National Library cod. 2823, f.1r

We need a name for the mixture of history and ontology that we find in the Bible and The Silmarillion. De-moralized modern materialism has no word for it, preferring a false dichotomy between "history" and "religion". And it is false - an artifact of discourse.

It's the simplest logic. Temporality - the passing of time - is a defining condition of our material existence and linear in nature. And linear temporality implies a starting point. We can count the tale of years - "material" history, but eventually we have to deal with year 0 or the problem of true infinity.

Either way, we are dealing with the transition into the finite and temporal from "something" else. Something meaning external to sequential time and physical space. That is, metaphysics crossing into physics. So if it strokes our egos to pretend that history can be purely "secular" - purely human - we only have two legitimate possibilities.

1. We set an arbitrary starting point for our story and forget about origins altogether.

Most historical writers do this by necessity - any history needs limits to be manageable, and temporal and spatio-cultural ones work well enough.

Jan Brueghel the Younger, God creating the Sun, the Moon and the Stars in the Firmament, 17th century, oil on copper, private collection

2. We acknowledge that a complete history - including origins - is impossible without ontology and metaphysics.

That is, those things only knowable by faith.

It's this complete, ontologically responsible notion of history that needs a name.

Maybe we just call it "history". But whatever word we use, the genius of the The Silmarillion is that like scripture, the historical narrative unfolds along more than one conceptual axis. It is a tale of the years of the world in that it starts at the beginning and moves forward in time, but it also spans levels of reality in order to get from divine creation to a material reality that we can recognize. The "history" begins with a monotheistic creator God outside of time and space, moves through supernatural beings like small-g gods and immortal Elves to mortal Men. The movement is temporal and ontological at the same time.

It's easiest to visualize:

There is a vast gulf of time between the divine creation of the universe and a mortal historian's recordings...

enanoakd, Eru Iluvatar timeless palace; Brothers Hildebrandt, Bilbo at Rivendell from the 1976 Tolkien calendar

...but there is also a vast ontological gulf.

They take place on utterly different levels of reality. In starting with one and ending at the other, you are spanning time AND ontology. This allows Tolkien to show how cosmic events like the making of the earth and the Fall into evil connect to the world of our experience.

God is the measure of Truth and Good because He is ultimate reality - the precondition of all that can exist. He precedes and supersedes creation itself. Divine creation is the source of Truth, and therefore the Good and Beautiful as well. But we can't see Him directly. But we can manifest his Logos in our limited way.

Finite material humans face moral choice in an uncertain material world and Logos is the means by which we make the right ones. Tolkien just makes it clearer. There is moral and aesthetic direction in Bilbo's work when he chooses to serve the truth as he can know it. This sincerity aligns him with God.

The Band has written a number of posts thinking about basic ontology and epistemology. Our mantra - what we can know and how we can know it - is essentially a call for ontological and epistemological responsibility in less technical terms. Our approach reflects the simple objective reality that human perception and understanding is inherently limited by our finite, subjective natures within a Fallen entropic world. There's no need to recap all of this here - the original two Silmarillion posts did that, and if you are curious and really want to delve into these questions, check out the Epistemology page at the top of the site for all the links.

What matters for this post is the observation that what we can know about reality - ontology - and how we can know it - epistemology - are related. Different levels of knowledge are conceptualized, represented, and communicated by different methods. This is actually incredibly obvious when you don't over-complicate. When it comes to fundamental questions about reality, the Band finds a simple, three-step ontological hierarchy connected by a vertical logos that manifests differently on each level is effective for the most general level of inquiry.

Ultimate reality - God, the fundamental basis of all that is and is not - is utterly beyond comprehension. Eternal, absolute - where inclination and Truth are the same thing. We can only conceptualize this figuratively and know it by faith.

Abstract reality - "absolutes" that we can conceptualize - like mathematical infinity, or human ideals - but can't exist in material reality. Theorems and formulas inferred from observation that are predictive are known by logic.

Material reality - the entropic, temporal, fallen reality that we physically inhabit for a few score of years. Where every measurement comes with uncertainty, every push into origins creates more mysteries, and everything dies. Knowledge here starts with empirical observation and then is modified by logic and faith.

These are broad categories but the point is to sketch out how we can know about the realities around us and not get lost in the weeds of philosophical speculation. Just enough detail to avoid the lies and vanities of Flatland. That is, the inane, masturbatory myths of secular transcendence - the collective delusion that we can know ultimate reality directly and impose abstractions on material reality. The Band considers secular transcendence the central error of the Modern/Postmodern version of satanic inversion masquerading as our "culture" today.

The most elegant observation to emerge from these posts was how ontology and epistemology move in unison - observation, logic and faith corresponding to material, abstract, and ultimate reality. As the subject moves up the ontological ladder, it gets closer to Truth, but our ability to "see" it gets more oblique and symbolic.

Shadow Art by Kumi Yamashita

And why does this matter? The Silmarillion absolutely nails this sliding ontological-epistemological scale in the form, content, and arrangement of its five parts. Each one narrates its place in history/level of reality in the way that we could know it in real life. And not just in the stories, but in how we experience the stories as readers. When the subject is ultimate reality, the story reads like scriptural allegory. When it's human events, it seems like a historical essay. Because this, its profound insights into human nature, the world around us ring almost impossibly true.

Ted Nasmith, The Hill of the Slain

The mound raised by Morgoth's Orcs of bodies of the Elves and Edain killed in the terrible Nirnaeth Arnoediad or Battle of Unnumbered Tears. Pride, vainglory, and grinding, tragic loss in a fallen world come through with awful clarity.

Despite this profundity, any attempt to assess Tolkien's literary value has to work around the intellectual and moral bankruptcy of modern literary studies and criticism. The first of the two original Silmarillion posts took up that cause, if you are interested. The important point is that with "literature" as an academic discipline unfit for purpose, we had to look elsewhere for standards. This turned out to be a good thing because it led us to useful terms and concepts in Tolkien's own work. Two sources in particular - Tolkien's old essay "On Fairy Stories" and the Forward to The Lord of the Rings - gave us a way to think about literature that isn't based on self-fluffing lies and inversion [note: "On Fairy Stories" was delivered in 1939 and published in 1947. Click for a link to the complete article. Click for the Forward in The Fellowship of the Ring].

J.R.R. Tolkien, The first Silmarillion map, 1920s, The Tolkien Estate, MS. Tolkien S 2/X, fol. 3r

It starts with the notion of sub-creation - a term from "On Fairy Stories" that refers to writing fantasy stories, but can apply to real artistic creation in general. The name is Tolkien's, but the idea ties into a fundamental idea about Western art - that humans create in God's image. The "sub" in sub-creation implies this relationship - human creation is a virtual, art-ificial version of the fundamental creative act - the creation of the real universe. The first detailed map of Middle-earth was drawn on an unused page from a University of Leeds examination booklet, but the level of care in creation is already clear.

This also ties into the basis of morality - the Good, Beautiful, and True are all characteristics of what is on the the most fundamental ultimate level of reality. Sub-creation reaches the material version of beauty, truth, and goodness when it is a material-level analog to this God-level primary Creation.

J.R.R. Tolkien, designs for Beren Gamlost's eraldic device, Tolkien Estate

This brings us to the second term from "On Fairy Stories" - the inter consistency of reality. The idea here is that the creation may be fantastical, but once the fantasy elements are introduced and accepted by the reader, the sub-creation behaves and unfolds in ways that are consistent with real patterns and relationships. It unfolds as if it is real - consistent with how reality unfolds in some way.

The inner consistency of reality describes how fantasy stories can ring true, while the most superficially realistic set-ups can appear contrived, wooden and false. It isn't the realism of the details, but the plot that rings true. The narrated actions.

Sub-creation and the inner consistency of reality define a deeper conceptual connection to to the truth than surface appearance. It's basically Aristotelian mimesis - the transformative imitation of reality that is the foundation of the Western imitative arts - applied to the specifically fantastical. The realism is in the moral, logical, spiritual, and emotional truths that the superficially fantastical characters act out.

We diagrammed the process like this:

Like any literary mimesis, sub-creation is a human construction, and therefore much simpler and clearer than the practically endless complexity and confusion of reality. This allows it to call attention to and highlight themes and ideas that are real but harder to see in everyday life.

It is the inner consistency with reality that determines if and how effectively a sub-creation can illuminate and enlighten.

Conversely, it is the lack of inner consistency with reality that makes nonsensical SJW perversions of culture empty. Their ideology is based on satanic lies intended to break our connection with reality, and have no insight to offer other than into their own degenerate imaginations.

And yes, it is bad - even worse than the form with the katana...

The word Tolkien uses for the way the inner consistency with reality lets a sub-creation illuminate some truths about reality is applicability. This appears in the Forward of the Lord of the Rings, not "On Fairy Stories", but fits perfectly with the older essay. He was using it to differentiate the meaning in his stories from allegory - a form of direct symbolism that is more restrictive than applicability. The older posts go into it in more detail - here's the link again. What matters here is that the sub-creation narrates relationships, principles, and connections that clarify and indicate truths about our messy existence, just not in a beat-for-beat symbolic or allegorical way. It is more flexible, more fluid, and therefore way more versitially useful. It's applicable. It's just that to make it work successfully, an author needs a creative imagination AND to be plugged into truth in a meaningful way.

Kip Rasmussen, Túrin Approaches the Pool of Ivrin

He is sub-creating an imaginary history that has the same inner empirical and moral principles as ours. Just clearer. This makes them applicable to a wide range of contexts rather than a single allegorical message.

This is applicability. Logos-based insights from replicating real patterns in an unreal structure. If the legendarium is a history of a world that could be ours, The Silmarillion distills it into something scriptural.

The Silmarillion is a sub-creation with an unparalleled inner consistency of reality, meaning its applicability runs to the most profound depths. It is a complete representation of that blend of history and ontology that we needed a term for earlier - from the divine creation of the universe to a recognizable material world. And not just on the level of content or story. How the actual structure of the book - how the five stories that make it up are written and organized formally and stylistically - conforms to what we can know and how we can know it in reality. This is an incredible artistic and intellectual achievement that needs a moment to dwell on.

Read that again. The inner consistency extends to the experience of reading it. It rings true as historical source material as well as a narrative anthology. As form as well as content in a way that doesn't happen in a traditional novel. This is because the five stories all differ formally - the style and structure of each matches how we can know the ontological-historical material being narrated. Of course, form and content - how it is written vs. what is written - are not hard and fast distinctions. Elements like style connect to both. But they allow us to consider the totality of the book in a systematic way.

Start with the five stories:

A structure made of five different narrative types means we aren't just reading descriptions of a reality akin to ours, we are uptaking information in the same epistemological way that we uptake real knowledge about our actual reality. Before we can even consider the content - plots, symbols, messages, what is communicated - we are experiencing the form of real knowledge. Together, the five stories have the form of truth. They reveal a world that isn't ours, but could be, in a simplified way that highlights the nature of reality and the meaning of the True and the Good within it. This allows it to explore the metaphysical origins and essences of morality and aesthetics - virtue and Beauty - and carry them into a temporal, material existence that we can recognize in our own.

Kip Rasmussen, The Music of the Gods

The Silmarillion presents the creation as a scriptural-type allegory, but with different images. Tolkien has stated that the Flame Imperishable is akin to the Holy Spirit, but his choice of music as metaphor for the angelic Ainur realizing God's plan is classical logos.

Logos in creation, the nature of evil, the fallen world, the importance of choice - fundamental truths that echo down through time and metaphysics that modernity has ignored to its detriment.

The way to best appreciate this achievement is to consider each part individually. To keep the sprawl under control, we will limit our observations to the workings of form and content in creating an applicable sub-creation. How structure and style simulate the experience of Truth epistemologically, while the actual narratives provide the substance. We're separating form and content for practical reasons, but the reality is that they are symbiotic.

The Ainulindalë (The Music of the Ainur) introduces us to the depth of Tolkien's internal consistency of reality philologically-sound imaginary languages. And the striking opening tells that we aren't in the typical world of fantasy.

Form:

Tolkien narrates the creation of the universe by Eru or Ilúvatar - his God - with a spare, lofty tone that is outright biblical in sparse solemn phrasing. In fact, this is very much a scriptural type of figural language or allegory - a narrative that reduces something beyond comprehension in terms that we can grasp. In this case, the production of the metaphysical entities called the Ainur who will sing the material world into existence.

Anna Kulisz, Ainulindale

Those opening lines: There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they were with him before aught else was made. And he spoke to them, propounding to them themes of music; and they sang before him, and he was glad.

The frame story is that this account was given to the Elves by the Valar - Ainur who entered into the world - in terms that they could comprehend. Epistemologically, this is how we have to represent things that are only knowable by faith.

If we visualize, we can see the consistency with the vertical ontology we just described. The projection of the metaphysical forces that shape the universe from ultimate reality can't be grasped in itself by finite material minds. The Ainulindalë uses the traditional Western mode for representing transcendental subjects - lofty scriptural figural lannguage or allegory. This is an unusual choice stylistically but it rings true to how we can have knowledge of this ontological level.

This gives the Ainulindalë it's inner consistency with reality formally,.

The chorus of Ainur singing Ilúvatar's world-theme into reality is not an allegory of Genesis. It is an allegorical creation story that is conceptually consistent with Genesis - music as a metaphor for the Logos of God's creation. It has applicability because it offers insight into the nature of creation in the West.

Content

There are some fundamental ideas laid down here that set the tone for the rest of Tolkien's universe. There should be - it's the Creation.

The Music of the Ainur

Creation is an act of logos - it is stated in the Bible, and on the human level, it is how we serve truth, push back against entropy, and resemble the divine image we were created in. Musical harmony has been a symbol of ordered, reasoned beauty in creation since before Pythagoras.

We looked at music as a unique art form that combines pure logic - the mathematics of harmony - and pure feeling - wordless sensation that goes direct to the emotions. Here's the occult post.

Content point 1. The fundamental importance of logos - order, harmony, reason, truth - to creation.

Tolkien uses the form of scriptural allegory but content from classical allegory - the music of the spheres - to highlight the connection between Goodness and Beauty with Truth and the divine order of reality. But this is only half of it - the material world is an entropic, fallen place, and the Ainulindalë has the inner consistency of reality here too. In fact, it goes further, using applicability to trace the connection between metaphysical things like the Fall of the Rebel Angels and the material human world that we experience directly.

Anna Kulisz, Ainulindalë – The Discord of Melkor

The Ainur aren't exactly angels, but occupy a similar place between God and man. Melkor, greatest of the Ainur, rebels Ilúvatar out of pride and vanity - the desire to create on his own or be his own God. And when thwarted, Melkor does what self-idolators tend to do when their greed and vanity is denied - they lash out.

Melkor shows us that evil comes from the archetypical Satanic inversion - rejection of ultimate reality for ultimate solipsism.

Content point 2. Evil is the rejection of logos - truth, reality, the divine plan - for self-worship and solipsism.

Many confuse cruelty or other evil acts with Evil - when they are in fact symptoms of it. Evil begins with the rejection of logos - of what is real - for will and desire. We exist in reality. We are subject to it, and when we die, it carries on. Claiming mastery is literally impossible - a wicked delusion that leads away from all that is and into ontological nothingness. It is literally the same, self-erasing "do what thou wilt" be your own god garbage that keeps coming up in the occult posts - has been the basis of evil since Lucifer opted to rule in Hell.

Satan and the Rebel Angels Cast out of Heaven

Melkor's desire might seem admirable at first - single-minded pursuit of vision is often praised. But his applicability clarifies the difference between luciferian inversion and healthy stick-to-itiveness. You see him degrade into utter wickedness as the stories in a way that isn't narrated explicitly in the Fall of the Rebel Angels.

Tolkien makes the continuum between solipsism - pride, vanity, self-idolatry, greed - and what we conventionally think of as "evil" in a modern sense obvious - misaligned desire taken to its ultimate end.

The problem isn't the desire to create. The problem is the rejection of ultimate reality - of God and Logos - to do what he wilt.

Content point 3. Evil can't create because it rejects logos, leaving it with what isn't truth, beauty, and the connection to divinity that is the definition of creation. It can only corrupt, invert, and destroy.

In the end Ilúvatar weaves all the music into the creation of the world, including Melkor's strife. In fact, the rebellion is revealed to be all part of the divine plan. But consider Melkor's response when Ilúvatar reveals that his secret desire for creative autonomy was foreseen all along: Then the Ainur were afraid, and they did not yet comprehend the words that were said to them; and Melkor was filled with shame, of which came secret anger.

Gustave Doré, "Nor more; but fled | Murmuring, and with him fled the shades of night" from Milton's Paradise lost. Illustrated by Gustave Doré, edited by Robert Vaughan, London and New York, 1866

Secret anger.

Melkor isn't the Devil, but his prideful rebellion against cosmic order has applicability. Same for the link between the exposure of vain posturing and gamma rage. Look at what it is that is so unbearable. That there is no creation "outside" of ultimate reality. It's all that can be. His desire is not just illegitimate and unjustified, it is impossible by definition. Insofar as Melkor can create anything, it is within the terms of ultimate reality, of Ilúvatar. Even his "discord" happens within Ilúvatar's music and is turned to Ilúvatar's end. But when his delusion bubble is punctured by basic facts, his reaction isn't to learn but to feel shame, then rage rather than facing his own skewed appetites.

And once he steps outside of music and into the world, all he can do is invert, debase, and shrink into Morgoth.

The Ainulindalë is a story of Creation and corruption with relationships that are applicable to logos, harmony, beauty, truth, God, and reality. And the lofty scriptural language is appropriate because that is how we represent these origins in our world. Genesis represents cosmic events in a language that we can grasp, even if the particulars are beyond us. We don't get exposition and extraneous detail - just a powerful solemn narrative voice declaring what is. The Ainulindalë rings true. The inner consistency of reality. What we can know and how we can know it.

The next story maintains the applicability through time and ontology by continuing to synchronize the inner consistency of reality in form and content.

The second story is also part of the creation cycle, but is less ontologically and historically remote and is written in a different style. It introduces something like a pantheon of "gods" in a mythological sense - super-powered beings that oversee the running of the world. A number of the Ainur come into the not-fully-formed world to rule over it and bring the themes of Ilúvatar come to fruition. The greatest are called the Valar and the lesser the Maiar.

Form:

Kip Rasmussen, Varda of the Stars

With the change in historical/ ontological level, the language changes again. Compare this passage to the Ainulindalë.

The Great among these spirits the Elves name the Valar, the Powers of Arda, and Men have often called them gods. The Lords of the Valar are seven; and the Valier, the Queens of the Valar, are seven also. These were their names in the Elvish tongue as it was spoken in Valinor, though they have other names in the speech of the Elves in Middle-earth, and their names among Men are manifold. The names of the Lords in due order are: Manwë, Ulmo, Aulë, Oromë, Mandos, Lórien, and Tulkas; and the names of the Queens are: Varda, Yavanna, Nienna, Estë, Vairë, Vána, and Nessa.

Spare and lofty Biblical language has been replaced by something like a transcription of older legends that you might find in a medieval compendium.

Tolkien originally conceived of his legendarium as something retrieved or recovered from the legendary past. The original idea was a mariner from the Undying Lands of the Valar washing up in medieval England, which became Bilbo recording ancient Elvish histories in Rivendell. In either case, the Valaquenta reads like the sort of thing a researcher in an old archive would find and copy.

The Valar and the Valaquenta fit what we can know and how we can know it. They bridge the gap between Ultimate Reality and the material world in a way that makes the connection clear, putting them on the abstract level of our ontological hierarchy. The idea of divine sub-creators echoes the Neoplatonic concept of the Demiurge, or abstract creative force between the world and God. That is, the abstract Classical thought between Christianity and the nations in the West.

Classical myths coexisted with Biblical revelation as symbols of ideas and concepts instead of "real" beings. The Silmarillion is different from the our world by representing the Valar as existing, but "On Fairy Stories" tells us sub-creation adds unreal elements to sharpen insights. The Valar being "real" within the narrative sub-creation shows us how Tolkien's applicability works.

The Valaquenta most resembles real mythology when it blurs the line between the Valar as anthropomorphic beings and forces of nature. It is impossible to reconcile the shaping of the earth through cycles of creation and destruction with the image of Manwë on a throne talking to the Elves. Tolkien uses the Valar figuratively - like medieval allegories of classical gods - and as real characters in his world at the same time. As Ainur at the creation, shapers of the world, and physical characters, they clearly show how abstract, metaphysical forces connect to our material reality in meaningful ways.

Content

Melkor also comes into the world, with the Valar, making the connection between his primordial rebellion in the Creation and the Fallen nature of the material world more obvious.

Stefan Meisl, Melkor

It is easy to see the contest of Melkor and the Valar as a mythologized version of the geological forces that shaped the real earth. A way of accounting for the earth sciences within the terms of the Sub-creation. In other words, the Ainur to Valar narrative connects the "Biblical" creation of the universe to the secular history of Tolkien's day.

Content point 1. The Fallen state of creation is spiritual, moral, and physical. They're all connected.

In an earlier post, the Band compared the Biblical account of the Fall to empirical limits on our understanding of the world. We used the widest concept of allegory as the common ground between two frames of reference so different that is is hard to even think of them together.

Those posts consciously avoided the existence of evil - the most obvious sign of the Fall - to focus on our relationship with the world. There's a remarkable overlap between the Fallen world as a valley of shadow seen as through a glass darkly, and an entropic universe of strange ambiguities and unknowable limits. Click for the second post. The same basic condition, just from perspectives so far apart that they seem opposite.

Giovanni Calore, Melkor

The Silmarillion tackles the nature of evil head on. Melkor condenses the physical and moral nature of the Fall in a single figure. The physical and metaphysical woven together in the most fundamental way. In the Band's terms, Tolkien gives us the fallen/finite world in a single memorable image. Think about that for a moment.

When he enters into the world, he is a force of evil like the Devil, but he is operating in an environment that he already altered.

Remember, Melkor's primordial Satanic rebellion was woven into the fabric of the universe in the Music of the Ainur. That this is part of the divine plan doesn't change the observation that the Fall has a moral and a material component.

Content point 2. Creation is still an act of logos and connects through order to the Good, the Beautiful and the True. Evil still can't create.

Anna Kulisz, Valar - Manwe

Morally, the clash between Melkor and the Valar over the shape of the world boils down to Logos vs. satanic inversion. The music of Illuvatar vs. do what thou wilt.

Physically or geologically, it plays out in the formation of a volatile empirical world that is supportive and hostile to life at the same time.

Making the Valar moral and physical abstractions as well as characters creates a degree of incoherence in their presentation but does what Tolkien says fantasy is supposed to do. It clarifies the connection between the Creation and Fall and our empirical and social worlds that can be hard to see. The Band took two posts to even try and spell it out. Writing this post, we realized that Tolkien saw the same thing - just articulated better in a different medium. We can't explain applicability any better.

Content point 3. It's a choice.

Melkor's rejection of reality is infectious - he corrupts a number of Maiar to his service like Satan's fallen angels. These include Sauron - the principle antagonist in The Lord of the Rings - and a number of others that are transformed into balrogs or demonic spirits of fire. Evil can't create. It can only mock and pervert with increasing ugliness.

thylacinee, The Balrogs of Morgoth

Bringing Melkor into the world physically shows how sub-creation simplifies and clarifies themes that are less clear in the real world. We have to judge Satanic inversion and secular transcendence by their fruits - the lies and their consequences. For us, pride, vanity, and do what thou wilt solipsism are internal inclinations and only become visible through experience. Melkor shows how the degenerative consequences of rejecting reality reverberate on every ontological level at once. And the self-destructive nature of this is more obvious when performed by a vile creature whose own stature dwindles and his depredations grow.

The next story is the by far the longest and makes up the bulk of the book. When most people think about The Silmarillion, this tends to be what they think of.

The Quenta Silmarillion is the story of the Silmarils - three enchanted jewels forged by the Elf Feanor - the most beautiful objects ever created by the greatest artist of all time. But the story is more varied ontologically and historically, starting with the conflict between the Valar and Melkor in shaping the world, the moving to the coming of the Elves and then Men. And as the distance between level of reality and human experience shrinks, the narrative tone changes.

Form:

The Quenta Silmarillion reads more like epic history in prose rather than a conventional novel, Biblical language or compendium account. But unlike the Ainulindalë or Valaquenta, the tone also changes over the course of the piece.

Murgen, Destruction of Illuin

We start with the continuation of the Valaquenta - Melkor and the Valar battling over the shape of the world. Tolkien uses the same mythic blend of narrative character-gods and natural forces to visualize the link between physical and metaphysical. Like Melkor as titan throwing down the Lamps that lit with world and plunging it into darkness.

But as the Quenta Silmarillion unfolds, the tone changes into something closer to epic history in prose form. Mixed media, to be more accurate, because Tolkien was a fine poet and adds lyrics and verse to his stories. But more "realistic" in the sense of less cosmic easier to visualize in real material terms.

This is where Tolkien's background in medieval history and literature really though. He doesn't try and copy the style of a real medieval chronicle or classical historical epic. What he does is much more profound. He structures his piece in the same way as high medieval history was put together.

Helge C. Balzer, Turin and Glaurung

Medieval histories often stretched back into mythical time - combining Biblical, mythological, and historical things into a single chronology instead of treating them as completely separate things. Like the blend of history and ontology, this needs a name. Something like epic prose or mythic history.

The main feature of this epic prose history is ontological change beneath the appearance of a continuous temporal narrative. It starts in a dim and legendary past and becomes more prosaic as it moves closer to the present. If the use of Valar and Melkor as abstractions and characters shows the connection between the moral and physical manifestations of Logos in Creation and the Fall, combining material and metaphysical accounts in the historical record acts the connection out in time.

This also makes sense epistemologically. Real-life legendary compendia and chronicle histories were assembled from out of older texts and accounts and these tend to be more precise and reliable the nearer they are in time. The further back you go, the more iterations and transitions the stories have gone through, and the less distinguishable they are from mythology.

With Elves and Men, the focus moves to the material level of reality, and here change is the defining condition. Or more specifically, change is the sign of the temporal, and temporality is the condition that distinguishes material reality from the timelessness of abstract and ultimate reality. Click for a recent post.

The Quenta Silmarillion doesn't read like a medieval history or epic, but it is structured like one. This lets it keep moving down the ontological hierarchy while adding an explicitly temporal dimension. Mythic-level early chapters read like an unclear mix of narrative action and metaphysical allegory while the later focus Elves and Men gives a more "human"-scale to the narrative.

Stefan Meisl, Minas Tirith upon Sirion

What started with mythic accounts of the shaping of the world in lofty Biblical-type language for the Creation moves through myth and epic stories to tales of individual characters. Clearer in detail but less universal in scope.

Clearer in detail but less universal in scope applies to the difference between the limited particularity of medieval history and the vague generality of myth. Empiricial human experience - with all it's variety and limits - in descriptive human accounts.

Map of Middle-Earth in the time of the Quenta Silmarillion

The geography where the more "historical" narrative of the Quenta Silmarillion takes place is consistent with this difference. The early mythic chapters take place all over Arda, while the war of Noldor and Morgoth takes place in a much more limited area.

Giovanni Antonio Magini, colored map of the European continent, printed in Cologne by Matthias Quad, 1604.

This one isn't "medieval" but it makes the point. Beleriand is clearly defined and described, but the world beyond the edges of the map are terra incognita. Moving from the metaphysical to the material gets local.

Content:

The changing tone and focus in the structure of the Quenta Silmarillion raises the first content point.

Content point 1. Mythic elements gradually withdraw as we move forward in ontological history.

The Silmarillion is applicable as a sub-creation because it is an imaginary history that could be ours. It has an inner consistency of reality that maps onto relationships in our existence. That means it has to come down from the higher ontological planes into something that we can recognize.

MrSvein872, Telperion and Laurelin

We can see the glimmerings of metaphysical division in the split between Valinor and Middle Earth. A star-lit wilderness marred by evil sums up Tolkien's vision of the material world. Haunting beauty inspiring the deepest passions but inevitably ending with decline and death.

The divide sharpens when the Elves - the first Children of Iluvatar - awaken under the stars in at Lake Cuiviénen in Middle Earth. After Oromë of the Valar discovers them, the Valar decide to bring them to Valinor to live among them in lives of safety and splendor. The choice proves difficult and many remain, through it becomes more and more clear over time that they don't belong.

Content point 2. Morality remains a choice.

The decision faced by the Elves is applicable. If the separating realms correspond to spiritual and material orientations, the Elves face the fundamental moral choice: follow Logos and live in what is literally called The Undying Lands, or follow seductive desire for material allure and slowly diminish. Devolving in stature and power into something like the fairy folk by Tolkien's day. Look how similar this is to real moral choice. How rejecting our place in the ontological hierarchy to wallow in spiritually-bankrupt materialism is a dead-end path to self-erasure.

Aulë, the smith of the Valar, clarifies the nature of Melkor's choice, and the relationship between logos, evil and creativity.

nahar doa, Aulë, Father of the Dwarves

Aulë is a Vala like Melkor so he has that same combined metaphysical-physical nature that makes him a character and a connection to Logos. He creates the Dwarves in the Quenta Silmarillion - beings that weren't "Children of Ilúvatar" but would have been the first sentient race in Middle Earth. This contravened Ilúvatar's plan that the Elves come first - like Melkor, Aulë put his own ambition over the divine plan. But what matters is the response.

Aulë accepts that he has wronged and prepares to destroy his creations. At which point Ilúvatar is moved and spares them - they just have to sleep until after the Elves awaken. It is the exact opposite to Melkor's petulance into rage spiral. Aulë accepts the divine order and subordinates creative ambition to logos. To reality. And the result is true creation. He is able to bring his masterpiece into existence - something original from the material of the world and not a corruption of something already there.

Content point 3. The world is fallen, and worldly evil can't create any more than metaphysical evil can.

Contrast Melkor with Aulë. Because he can't create something new - his perversions require him to expend his own power. Without the ability to bring creation into reality, it's a zero-sum game. All three of the Quenta Silmarillion content points come together here.

Thylacinee, The Balrogs of Morgoth

As Melkor's terrestrial power grows, he diminishes. The titanic might of the continent-busting Vala slowly dispersing into the world shows us mythic elements gradually withdrawing as we move forward, the real connection between the physical and metaphysical Fall, and the importance of choice in all of it.

Renamed Morgoth, Melkor rules from his fortress Angband as a Dark Lord. As he diminishes, his evil spreads, but he remains the only Vala physically present in Middle Earth. Ontologically, the greatest "supernatural" power in the material temporal world is the primordial, inverted one. The Prince of this World, you might say.

So the choice of the Elves is that choice - Logos or the Father of Lies.

Content point 4. Tolkien's Elves are central to his sub-creation and applicable to fundamental moral and conceptual choices in material reality.

Laura Tolton, An Ancient Enemy

Tolkien's Elves are central within the narrative and for the larger applicability. In the story, they are physical beings of human form, though taller and more slender on average, and far more beautiful. They are also far more capable - immortal from natural causes, stronger, faster, more durable, and able to wield considerable magical and artistic forces. In The Silmarillion, the great Elves approach Maiar in power. Like Glorfindel here, who kills a Balrog - a fallen Maia corrupted by Melkor - in single combat before falling into the abyss with his foe.

This also explains why Glorfindel - reincarnated from the Halls of Mandos before the end of the First Age and sent back to Middle Earth - was able to repel the Nazgul in The Lord of the Rings. First Age Elf-Lords were beasts. This lofty status is what makes them applicable to real life issues. The fatal errors stand out so starkly.

There is nothing in history or literature quite like Tolkien's Elves, although aspects of them come from different traditions. There's a remark in "On Fairy Stories" that the power of imaginative creativity - making sub-creations with the inner consistency of reality - is Elvish. Think of the Elves as an insight into human creative potential and the tug-of-war they face between lingering in the twilit lands and passing into the Undying West makes sense. Human creative potential is constantly pulled between the beguiling beauty of the material solipsism and the abstract or spiritual call of what is true.

Creators are at their most "Elvish" when their imaginations engage with the world to express higher truths. They start in Middle Earth, but have to choose the turn to Logos to really go anywhere. And the inverse of the Elf - Morgoth's corrupted perversion - is the Orc. A bestial atavistic creature without any higher creative functions or imaginative sensitivity at all. A proto-SJW.

Content point 5. The Elves give insight into the nature of creativity.

The Quenta Silmarillion focuses on the Noldor - the middle of the three tribes of Elves and the most gifted smiths and artisans. Unlike the lordly Vanyar or seafaring Teleri, the perfect group to use to explore the nature of art. The Noldor are closest to Aulë, who teaches them the arts and crafts. So creativity comes through the Vala who followed Logos and carried the Music of the Ainur into the material world.

breath-art, Fëanor and Silmarils, digital art

Fëanor was the greatest of all craftsmen, but doesn't create like the Valar - transforming the earth and generating species. He takes materials already created and reconfigures them into something more beautiful or more profound. "On Fairy Stories" gave us the term for what he is doing:

He is sub-creating.

A Silmaril is an imperishable crystal containing the living light of the Trees and hallowed by Varda. It combines ideal metaphysical purity and perfect material form.

Content point 6. The Silmarils represent the fundamentals of artistic creativity in the West: Logos + skill = beauty.

The Band sketched out a basic Western concept of art in some posts posts on the roots of Western culture. Most simply, art is the combination of higher principles and material craft skill.

The Greeks used the terms episteme - higher principles - and techne - refined artisanal skill coming together phronesis - principled creation. If interested, click for the post on the episteme + techne = phronesis formula, and how it aligns with the vertical logos that defines the West.

Episteme is just Logos, or alignment with Truth as understood. The Silmarils physically combine perfect craft with metaphysical light. They are archetypes of artistic beauty. Man-made beauty at the limit of perfection where it just brushes against Beauty.

Ted Nasmith, Felagund among Beor's Men

When Men awaken, the metaphysical is even further away. The text isn't even clear on their origins. The corrupted encounter the servants of Morgoth directly - Prince of this World. But there are no Valar to guide them. Those that learn about beauty and virtue do so from the Elves.

Men who wish to align with the theme of Ilúvatar can only access Logos at the end of a long chain of transmission: Ilúvatar to Valar to Elves to Men. From a narrative perspective this seems odd. But if we think of applicability, evil is directly present in our Fallen world, while Logos is seen as through a glass darkly.

How does Finrod elevate the first Men he meets? With music.

Content point 7. Beauty expresses the Good, but objects - or people - of great beauty can trigger unwholesome desires in flawed individuals.

The two-edged sword of creative power. Melkor's lust for the Silmarils is obvious, but they introduce conflict among Elves too. Fëanor and his sons are already filled with jealousy over issues from his blended family and their possessiveness pushes them into madness. Again and again they choose material desire over all else.

The Death of Maedhros

Maedhros was one of two of Fëanor's seven sons to survive the wars with Morgoth. He cast himself and a recovered Silmaril into a fiery chasm rather than surrender it to the Valar and face justice. Greed and desire to madness then self-destruction.

This is different from the complete animal inversion of the Orc. It's the luciferian path. Pride, self-idolatry, and the impossible fantasy of being your own god. Fëanor believes in the absolute power of his own genius and will, and wound up serving the Prince of this World, even as he thinks he's denying him, and drags his family into ruin.

Creation is a passionate act, but passion is not "good" in itself. Misaligned, it can be as disastrous as pure evil - it certainly plays into pure evil's hands. Fëanor's rage and pride even bring war and death to the Undying Lands, just as the discord of Melkor tainted the Music of the Ainur.

Fëanor and the Noldor bring the applicability of the Aulë/Melkor choice - logos or luciferian solipsism and ontological ruin - from the abstract to the material level of reality. As far as the Elves apply to creative potential in the real world, it makes it applicable to us. Tolkien shows us that creative drive isn't black and white. Artists needs fire and ambition to martial their powers and shape the stuff of the world into something beautiful or profound. But these same powers easily lead into vanity, and lust. The question is whether they align their visions with Logos, or descend into solipsism and serve lies.

Lady Elleth, Nerdanel

The wife of Fëanor was a great sculptor - strong-willed and curious. But they grew estranged as he was consumed with greed and vanity and she did not follow him to Middle Earth.

She chose correctly but still suffered for his evil.

Tolkien uses art - music and craft - in The Silmarillion as metaphors for the chain of Logos connecting ultimate and material reality. This also highlights the chain of Logos connecting Creation and sub-creation - the artistic process. When Men embrace truth, they are as Elves, and plugged into an ontological hierarchy stretching all the way to God. Alternatively, they can embrace the "spiritual" entity that rules this realm and reap the inverted rewards of a Fallen world. Power, domination, stuff. Material rewards that die with you are all the Prince of this World can offer. He rejected the higher things.

Content point 8. Basic morality follows consistent patterns from ultimate reality through the history and ontology that are indicated by creativity.

The world is created in Logos, but there is no Jesus - yet - so Logos is expressed in the Classical metaphor of music. The Fall is captured by discord. In the fallen material world of Men, the metaphysical is very far away, ontologically and temporally. But what doesn't change is that creation is a sign of alignment with Logos on every level.

Near the beginning of this post, we described how The Silmarillion moves through time and ontology together. Thinking of this through creation looks like this:

Coming down and moving forward - getting more material and closer in time - creation is the consistent tell for alignment with Logos, Truth, and Beauty.

We can visualize the way the form also synchronizes with these categories, maintaining the appropriate kind of representation for the onto-historical distance.

If we combine them, they look like this:

Even as the metaphysics of Truth become more distant, the pattern and the choices remain the same. They're just harder to see.

It isn't a coincidence that Men who ally with the Elves and their vision are called the "Faithful". In the Band's terms, faith is how we know metaphysical things epistemologically. Like vertical Logos in a Fallen world.

Wherever you are, however it is depicted, the basic choice is the same.

Content point 9. You can't fight Not-Logos with not-logos.

Calling our higher potential Elvish - the creative, virtuous, reality-facing aspect - gives the growing division between Valinor and Middle Earth a moral applicability. The Undying Lands can represent an abstract ideal alignment with Logos that is materially impossible, and Middle-Earth an alluring world of deception and death under a satanic overlord. We can read the Noldor returning to Middle Earth on a mission of vengeance, greed, pride, and violence as turning from Logos and wallowing in earthly appetites.

Stefan Meisl, The Noldor Crossing the Helcaraxë

The journey back is certainly consistent with descent into a fallen state. Fëanor brings his followers out of Valinor through a bloody path of betrayal, while his half-brother Fingolfin led the bulk of the Noldor through a horrific frozen waste where the landmasses meet. They pass through death and suffering to enter a land of death and suffering.

But falling into the enemy's Fallen realm to fight him with his tools is a fool's errand. This is such a valuable lesson. There is no "beating evil" in this world. You can win battles, gain temporary advantages, but ultimately the path of Logos leads away from the material world. This is the valley of shadow - of Morgoth's twisted perversions - where the Elvish is cut off from metaphysical spiritual nourishment and withers into parody on the way to oblivion. It's vanity and wrath that drive the Noldor to turn their backs on Logos and reality for their base, materialist instincts. And when the inevitable happens, there is no faith or even virtue to withstand the puncturing of illusions.

There is only despair.

Kenneth Sofia, Fingolfin Rides to Angband

Despair leads Fingolfin to a suicidal dual with Morgoth - a reminder of the power of the Elves and the reduction of Melkor. Morgoth is trapped in his massive physical body, and these wounds torment him for the rest of his days. But the High King of the Noldor is destroyed.

Denethor repeats this sinful error in The Return of the King.

Content point 10. But you do have to fight.

The invariable patterns of a Fallen world don't mean that evil always wins. The whole point of aligning with Logos is to avoid the snares vanity and secular transcendence as much as possible. Failure is relational - there is no failing without a commensurate notion of success to measure it against. Even the vainest of creatures - the Noldor - are capable of moments of stunning beauty and achievement.

Mysilvergreen, Hurin and Huor are landing in Gondolin

The issue isn't whether to resist evil, it is how you choose to do so. The destruction of the Trees and theft of the Silmarils was the consequence of earlier moral blindness - the decision to chase Morgoth to Middle Earth is both a repetition and a doubling down. Tolkien doesn't tell us how this could have played out differently - just that repeating cardinal errors is the wrong way to go.

Elena Kukanova, Return

Finrod Felagund was the finest of the Noldor in Middle Earth - a harpist, warrior, and Elf Lord who was closest to Men. He sacrifices his life to keep an oath to save the hero Beren and is untouched by the crimes of Feanor and his sons. We are told that his time in the Halls of Mandos was short, and he was reborn quickly and reunited with his beloved in Valinor.

Melkor's dispersal shows us that the Fall is intrinsic in the material world - Middle Earth in the narrative sub-creation. We already knew this, but Tolkien makes it much clearer. Material power used to build, protect, and serve truth is a measure of virtue. It's seeking it as an end in itself that is the path to ruin. Just because everything inevitably falls, it doesn't have to be during our watch.

Content point 11. Faith is required in a Fallen world, and with faith, love and and resolve can make miracles happen.

Peter Xavier Price, Elwing Bearing the Silmaril

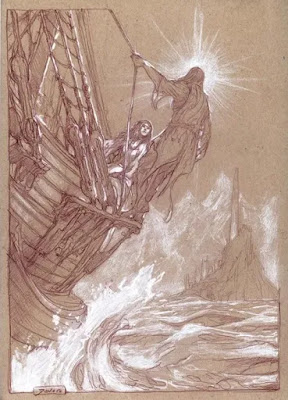

Eärendil was the Man who sailed for Valinor as the remnant of Elves and Faithful are pressed to the limit by Morgoth and their own greed-driven in-fighting. Basically, the anti-Feanor. He passes through the fog and illusion around the Undying Lands with a Silmaril. The one retrieved from Morgoth by his ancestors the Man Beren and the half-Elven half-Maia Luthian and brought by his Elven wife Elwing in the form of a dove.

Elf-Man pairings are rare and significant in the Legendarium, but consider the applicability of this story. The dove and star as signs of deliverance through Logos speak for themselves. More symbolically, it is Man acting in alignment with our Elvish nature and following a purpose of selfless purity that brings salvation.

Tolkien uses the term eucatastrophe in "On Fairy Stories" for the sudden wondrous reversal that makes fantasy uplifting. The reverse of catastrophe - deliverance in an unexpected and and miraculous form. He calls this the ultimate inner consistency of reality, because it applies to the ultimate eucatastrophe - the Incarnation and the hope that it brings into a Fallen world.

Donato Giancola, Eärendil and Elwing Approach Valinor

By now it's clear how applicability works. Eärendil's story isn't an allegory of Christian redemption but it clarifies and illuminates the same basic truth.

Eärendil - a Man supported by an Elf and wielding a light from an older world - shows the human potential for salvation when our higher nature is harnessed to the vertical chain of logos. Properly aligned, we cut through the deceptions and snares of this world and points to the Truth.

Some of his key points:

The Valar know he's coming. Salvation through Logos is foretold.

He asks for help. Salvation requires putting reality over vanity

He petitions for everyone. Salvation is universally-accessible.

He ascends as a star. Salvation is personal eucatastrophe.

Eärendil cannot return to Middle Earth - another plot point that makes more sense when we consider the Valinor-Middle Earth split as applicable spiritually. Salvation is a one-way trip. In the sub-creation - The Silmarillion - spiritual and conceptual relationships are represented by narrative events, so Eärendil can't physically touch down on Middle Earth soil. But he can destroy Morgoth's great dragons from the sky.

Manuel Castanon, The Dragon and the Star

Applied to reality, he's a sign.

We could go on - the Quenta Silmarillion is impossibly rich. Once you see how Tolkien is spinning applicable insights out of his sub-creation, there is no obvious end.

The fourth story is much shorter - more like the first two than the Quenta Silmarillion, but focused o men. This brings our chain of closer to the world of our experience.

This story moves from the First Age into the Second, and largly avoids Middle Earth for the island of Numenor - an land given to the Faithful after the fall of Morgoth that develops into an advanced civilization of its own. This is the Golden Age of Men, but the pattern is predictable.

Form:

The style shifts again - into something resembling an historical account from a old archive or monastery. This story is squarely in the world of Men - the material world ontologically, though closer to the transcendent than we are now. On this level, knowledge is conveyed by straightforward history. With the details and gaps that that entails. Look how it is framed. It opens like a chronicler's set-up:

Alan Lee, Minas Tirith

"It is said by the Eldar that Men came into the world in the time of the Shadow of Morgoth, and they fell swiftly under his dominion; for he sent his emissaries among them, and they listened to his evil and cunning words, and they worshipped the Darkness and yet feared it." It reads like something in a library in a Third Age city of Numenorean descent like Minas Tirith in The Lord of the Rings. But while the mode may be different, the notion of moral choice in a fallen world is the same.

Events from the end of the Quenta Silmarillion - just a few pages earlier - are recounted as from an older remote source. In this case, a song: "in the Lay of Eärendil it is told how at the last, when the victory of Morgoth was almost complete, he built his ship Vingilot, that Men called Rothinzil, and voyaged upon the unsailed seas, seeking ever for Valinor; for he desired to speak before the Powers on behalf of the Two Kindreds, that the Valar might have pity on them and send them help in their uttermost need. Therefore by Elves and Men he is called Eärendil the Blessed."

The form of the Akallabêth has changed to chronicle history., the ontological level has come down to the material, and the historical distance has narrowed to the world of men.

Vertical Logos is so compelling because it manifests differently on different levels but always points back to the same truth. It is a guide through the valley of shadow. Tolkien captures this in the way his narratives change modes but echo the same themes as they move through time and ontology.

Content:

The form changes, but the themes are consistent echoes of fundamental choice - the one the Band has been hammering at from the beginning: Logos and truth as you can see it, or vanity, secular transcendence, and Satanic inversion.

Sauron in Numenor

The Numenoreans become vain and corrupt - high on their own achievements - and return to Middle Earth as conquerors. Morgoth's lieutenant Sauron appeals to their vanity, leading them to oppress the Faithful, worship Melkor, and finally challenge the Valar for control of the world. Numenor is toppled beneath the waves and destroyed, the Faithful flee to Middle Earth, and the Second Age ends.

Ted Nasmith, The Ships of the Faithful

In an echo of Atlantis - the Faithful were warned and flee the destruction of the island. Arriving in Middle Earth, they found Gondor and Arnor - two kingdoms that echo the splendor of lost Numenor - and continue the fight with Sauron into The Lord of the Rings.

This story is applicable secular transcendence. Human society, no matter how high-minded, cannot attain worldly perfection or supplant Logos or the divine order of reality. But that is the heart of Satanic inversion - desire, vanity, and self-idolatry over what is true. Over and over, with the same disastrous outcomes..

Content point 2: The material world falls further from the metaphysical - with Valinor moving beyond the physical reach of Men

After the Numenor debacle, the Valar change the world again - this time "bending" it into the spherical form of Tolkien's day. The straight path to Valinor remains for the returning Elves and a select few others. For everyone else, the separation is complete.

Geoff Simmonds, The Breaking of the World

Brilliance - "bending the world" gives us the physical world of the 20th century and the applicable stories of The Silmarillion in the same reality. And ties it to our own fallen nature. By repeating the Falls of Melkor and Feanor, the Numenorians cut themselves off from the true nature of reality.

Applicability.

"Because narrow is the gate and difficult is the way which leads to life, and there are few who find it." Matthew 7:14.

It is also notable that as the world becomes more material, it isn't just Logos that gets harder to see directly. Evil also continues its pattern of dispersal that started when Melkor began expending his own energy on corruption. Sauron is a dark lord in the manner of Morgoth, but on a lesser scale. A Maia not a Vala, his pattern is similar, but he is an agent awakening and fueling evil rather than originating it.

The last story is a short historical account that picks up Sauron's story at the end of the First Age and carries it to the time of The Lord of the Rings - the end of the Third Age and passing of the Elves from Middle Earth.

The fifth narrative is less of a standard story - it's closer to the appendices of The Lord of the Rings

in the way it covers backstory and connects the events of the other four to Tolkien's other books. But it is part of the actual Silmarillion and its unusual style continues the pattern of changing narrative modes to match historical and ontological levels.

Form:

"Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age" reads differently still. It is clearly material human history but is more of a broad expository summary than an account of one place like Numenor.

This wide scope makes it applicable a different way - the broad patterns laid out in the other books are shown unfolding in time. The cursory accounts reiterate the same central insights that we've seen repeat and echo through real history. But now we've seen why the rejection of Logos for leads through solipsistic vanity and greed, to luciferian self-idolatry, to ruin.

Content:

Sauron's shape-shifting shows us how Evil can be alluring. Tolkien calls him fair-seeming - another way to put it is that the Devil can quote scripture.

Content point 1: The righteous struggle to recognize and understand the nature of evil.

Elena Kukanova, The Temple of Melkor

Humiliation and self-interest drive the turn from Logos - just like Melkor and akin to Feanor. Then Sauron was ashamed, and he was unwilling to return in humiliation and to receive from the Valar a sentence, it might be, of long servitude in proof of his good faith; for under Morgoth his power had been great. Therefore when Eönwë departed he hid himself in Middle-earth; and he fell back into evil, for the bonds that Morgoth bad laid upon him were very strong.

And once again the metaphysical choice is narrated geographically in the sub-creation. Staying in Middle Earth as opposed to returning to Valinor. Committing to solipsistic materialism or reconnecting with Logos.

Sauron Annatar

Sauron seeks to corrupt the Elves that remained in Middle Earth and appeals to their vanity with magical thinking and secular transcendence.

Celebrimbor, greatest Noldor craftsman since Fëanor is seduced by Sauron's fantasy of defying realty through will and desire. Rewriting logos. Being your own god.

And with Sauron's knowledge and help, makes the Ring of Power and plunges the world back into darkness. Technology - human creative power, passion, and imagination can create wonders or self-immolation in the flames of vanity.

There is a lesson here that the Band has pointed out again and again. How does one deal with the fair-seeming of evil? How do you see through the honied words and appeals to your own vanity?

It's not like Sauron hadn't amassed enough of a track record to merit special attention rather than literally be taken at face value.

Content point 2. It's still a choice. And magical thinking doesn't make reality not real.

The geographic split between Valinor and Middle Earth is applicable to the metaphysical one between Logos and solipsistic materialism. If the Elves embody human creative potential, the ones laboring to transform a Fallen entropic material world into an impossible paradise embody its waste on the pipe dreams and glamours of secular transcendence. We know how self-erasing this. It is the modernity that we are pushing against.

Consider this quote, apply the metaphysical split between Tolkien's worlds spiritually, and think of the modern lotus eaters as they sell out their nations for fancies:

J. R. R. Tolkien, Sauron, watercolor

It was in Eregion that the counsels of Sauron were most gladly received, for in that land the Noldor desired ever to increase the skill and subtlety of their works. Moreover they were not at peace in their hearts, since they had refused to return into the West, and they desired both to stay in Middle-earth, which indeed they loved, and yet to enjoy the bliss of those that had departed. Therefore they hearkened to Sauron, and they learned of him many things, for his knowledge was great.

Is there better metaphor for parasitic materialist globalism draining the historical achievements and legacies of the West?

The choice is best expressed by Galadriel - Finrod's sister and greatest of the Noldor who remained in Middle Earth after the end of the First Age. Her own Ring allowed her to maintain her stature of a mighty Elf lord into the time of The Lord of the Rings - to defy reality with technology. But not really - should Sauron gain the One Ring, he has the ultimate control. In the end, what is real is real and secular transcendence only leads one way. Not the one-way path of salvation either.

Incantata, Galadriel

Galadriel is wrapped in secular transcendence. She places desire over Logos, then uses technology to compensate. But when the One Ring falls into her hands, she opts for Logos and rejects its worldly power for truth. In other words, she turns off the fake media reality, puts down the fancies, and accepts reality. It's applicable.

The One Ring represents the will to earthly domination, but that's a story for another time.

"Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age" ends with the last Elves leaving Middle Earth. We know from the Legendarium that they were joined by a few mortals who earned it - Gimli the Dwarf who will meet Aule, and the Hobbit Ring-bearers - Bilbo, Frodo, and later Sam.

Ted Nasmith, Legolas and Gimli Sail to Valinor

Gimli earns passage alone of his people by his bond to Legolas and devotion to Galadriel. That is the Elvish as Logos-facing in the sub-creation. And Legolas is an Elf.

Content point 3. Evil is depersonalized, but it exists in the world. And we can understand how it operates.

The Ring was the last direct contact between Middle Earth and Ainur - the abstract level of ontology - in the narrative. When Sauron and his works evaporate, evil has become fully disembodied. It makes sense that the surviving individuals who handled this object and brought it to its dissolution also pass out of their world. The fruits of their actions brought about a change - not just in Age, but in the nature of reality. Their connection, like the Elves, was to the old form of Logos - a journey to Valinor within the narrative. And the door closes behind them.

Darrell Sweet, The Gray Havens

The world they leave behind looks like ours.

But the choices are the same as they ever were.

In a way, Tolkien called his shot. His terms from "On Fairy Stories" and the Introduction to the Lord of the Rings traced out an artistic process deeply rooted in Western tradition and aligned towards the True, the Beautiful, and the Good. This is not superficial allure, although Tolkien is a sublime writer and The Silmarillion is definitely alluring. This is artistic beauty - material beauty - when technical skill combines with logos to reveal insight about the reality around us. It is a deeper realism - an inner consistence of reality - that is more profound than surface resemblance. It is applicable. Clarifying and illuminating truths that are not so clear in our chaotic realities.

The Silmarillion is so applicable because it is consistent with reality internally and externally - as form and content. It fuses ontology and history - moving through time and levels of reality through five stories, each written as it would appear in real life. We experience the content as we would real content of comparable ontological-historical distance. It's ringing true before we've even processed the storylines.

Kip Rasmussen,

Luthien finds Beren

The content of the stories is symbiotic - filling the convincing forms with narratives that align with our reality and highlight truths about our fallen world. And since they move from the creation to the present, they show us how patterns that we see around us echo through time and metaphysics from the very beginning.

Complete history we called it at the start.

WisesnailArt, Finrod crossing the Helcaraxe

Readers will accept almost any number of fantastic elements so long as they react to each other in rational ways - that is, ways that correspond with our experience. The idea that an elf-lord could succumb to his own hubris and destroy himself and most of his people is more believable - rings more true to our reality - then the projected globalist atavism that passes for modern "drama". And when those characters have the power, gifts, fire, and inherent nobility of the best of the Noldor - like Galadriel's brother - their fall is all the more poignant and cautionary.