If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts have a menu page above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

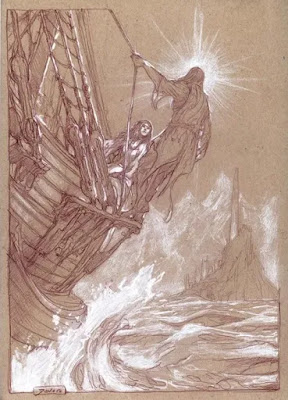

Benjamin Harff, Illuminated Silmarillion, 2009, pen and ink on paper

This is The Silmarillion post - an application of the Band's investigation into the roots of the West to the arts of the West. We're debuting a new angle by looking at the good, the beautiful, and the true in a positive way. Because it is one thing to grasp how vertical Logos ties reality together conceptually, and another matter altogether to experience it through the eyes of a profound artist.

We've spent a lot of time on what art isn't. Time to see what it is.

It's a big post - considered splitting it in two - but it flows and there are a ton of pictures. Thanks to all the Tolkien artists out there, we could maintain our multi-media approach while sticking to a single book. We hope you stay for the show - The Silmarillion radiates the beauty, brilliance, and sheer logos that only comes into the world when arts of the West are firing on all cylinders.

formenost, Alqualonde

A quick note on what we are doing, and where to find the background information for the ideas used in this post. The Band has spent months working through what is possible for us to know and how we can know it as a way of tracing out the real roots of the West. Modern globalist culture is incoherent because it is founded on fundamental falsehoods - self-serving myths of endless progress and human perfectibility. Technological progress has allowed us to pretend this magical thinking is real, but there are no more frontiers to exploit and the world of tomorrow is running a bit late.

John Gast, American Progress, 1872, oil on canvas, Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles

Real American wages over the last 50 years.

If this system were real, the consequences of doubling the labor force, importing waves of low-cost workers, and outsourcing production would have been dismissed a sociopathic and retarded, not progress.

Yet here we are. How's that return to the moon going?

The webs of deception are so deep, complex, and fundamental to the modern world view that they are impossible to unravel on their own terms. Every layer reveals more layers, every example connects to more examples. It's a hall of mirrors built from countless threads over many lifetimes. But if we switch distances and look at the meta-patterns, it all traces back to the same primary error: that finite minds can perceive absolutes clearly. It's an endless conga line of self-serving vanity that feeds off a desire to trust authorities. Once it became obvious that the whole thing was rotten the only thing to do was tear it down and start over with what is actually epistemologically possible. That project isn't finished, but it is far enough along that it is now possible to consider cultural practices in an ontological, empirical, and historical frame of reference that is coherent and reality facing.

What Western culture is, rather than what it isn't.

The postcards are misleading. The West isn't great buildings. The great buildings express the national cultures of the West.

Packaging "culture" as tourist experience inverts the causal relationship.

This process was long enough that just recapping it eats up a lot of space, so we decided to break the post in two. Part 1 has a good summary of where we are coming from conceptually, and what the terms that we refer to mean. It also did a lot of set-up by looking at the corruption of authorized "Literature", and how Modern discourse made Postmodern inversion inevitable. As an alternative, we went through Tolkien's essay "On Fairy Stories" and found an attitude towards imagination and literary creation that aligns seamlessly with what we can know and how we can know it. Making that its own post puts the background in one place for those who want it - if you are more interested, all the posts are in the archive on the right and a lot are in the Epistemology page above. It also frees all of this post for The Silmarillion itself. Because that book needs it.

First an introduction.

The Silmarillion was edited and published in 1997 by Tolkien's son Christopher with assistance from future fantasy author Guy Gavriel Kay four years after J. R. R.'s death. Click for a link to the full text, but this one is worth buying.

Although it was unfinished, the book is the backbone of Tolkien's imaginary world. The ideas in it go back to his earliest writings in the nineteen-teens, and according to the link, he pitched the idea as a sequel to his hugely successful The Hobbit in the '30s. When it was rejected, he went on the write The Lord of the Rings, but continued working on the stories in The Silmarillion until the time of his death.

It turned out to be successful after all.

It is not necessary to understand Tolkien's larger world to appreciate the power of this book - like any great work of art, it stands on its own. But it is important if you really want to grasp the brilliance of Tolkien's literary imagination and why an omni-nationalist voice for the West like the Band considers him the greatest author of the 20th century.

A note on greatness.

The set-up post split discourse - the false, secular transcendent nonsense that passes for reality in modern cultural institutions - from the empirical human reality of organic culture formation. For this post, you just need to walk into a contemporary art gallery or read Postmodern literature to see the huge gulf between the lofty claims and prestigious spaces and the crap that actually appears there. Like the Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History in Münster

They want you to feel confused, angry, stupid, and insecure. They're sociopaths.

It seems to be a cosmic rule that evil has to reveal what it is doing in some level. From a Christian perspective, the argument would be that the acceptance of evil has to be freely chosen. And it appears that the "respected" institutions of higher culture have to show that they have been morally and metaphysically corrupted by inverted gibberish, rabid atavism, and pure cultural toxin. The hideous Art! is "applicable" in Tolkien's terms because it is a material reveal of a spiritual cancer. At which point you have a choice: you place these perverse and hostile "authorities" over your own eyes, mind, and moral judgement, or you recognize the lies, reject the perversion, and seek Truth and Beauty to the extent that you can. Only one maintains your integrity as a person, but either way, it's your choice.

Like the Star Trek episode where an interrogator attempts to break Picard's mind and get him to admit that he sees five lights when there are four. It's a variation on the 2 + 2 = 5 in 1984. Postmodern art is similar, except that it doesn't insist on a specific lie. Claim however many lights you want, so long at it isn't four.

Just another Satanic inversion really - one of the many manifestations that define official culture. This version boiled down to a single sentence: things are different in discourse and real life. So it follows that what the discourse calls "great" isn't.

In an organic culture, artistic greatness is emergent. Someone creates things that resonate with enough people to become popular. If they remain popular long enough, they pass into the collective unconscious and join the group of references and assumptions that define a culture. Discourse inverts culture by pretending that these natural processes must conform to imaginary metaphysical universals. They don't. Enculturation is unpredictable - sets of interactions between peoples and contexts over time. Theory and criticism are supposed to provide commentary and insight into this cultural activity, not the rules to govern it. One theory to rule them all...

Robert Motherwell, Frank O'Hara, René d'Harnoncourt, Nelson Rockefeller at the opening of the exhibition Robert Motherwell, curated by O’Hara, 1965. Photograph by Allyn Baum, The Museum of Modern Art Archives

Frederick W. Kent, Art history lecture using a slide projection of images, The University of Iowa, 1960s

Modernism in the arts can be summed up as atavistic grifters and sociopaths using globalist money to suppress and replace natural organic culture formation with discourse. The MOMA blog is actually called inside/out... They have to show it.

Think of generation after generation of bright young college students making huge personal and financial investments in trusted institutions, only to be fed this inverted horseshit. An intellectual culture where it is axiomatic that empirical human nature and enculturation are ignorant and primitive. Where admission is based on denying four lights.

When entry into respectable society requires the denial of reality, how do you engage with the world around you in a meaningful way? The whole system leverages social pressure and human nature to condition you to break trust with empirical observation and natural cultural formation. Your own aspirations grease the choice to buy in, and sticking around requires everyone uphold the system. So justifying your choices means accepting the inversion and becoming fragmented and uncertain. Needing to trust the "authorities" and not the self. Cognitive dissonance, weird emotional incontinence, and learned helplessness all result.

The Band looked at Tolkien's "On Fairy Stories" as an alternative to the psychic dissociation and atavism of modern discourse when thinking about greatness. Two ideas jump out - Sub-creation and the internal consistency of reality.

Sub-creation is Tolkien's word for the artistic process. Ideas expressed in a creation based on images derived from this world, but not tied to it. What matters is that the representation unfolds as if it were real. The reader relates and connects with it because it rings true. The internal logic is consistent with the reality around us.

This is where the roots of the West comes in. Modernist discourse is a post-Enlightenment secular transcendence. It claims absolute truth-value that is not possible to limited humans and pretends that supersedes observation and logic. This makes discourse autonomous - it isn't the result of any outside factor because it supersedes them. What we see as "outside factors" are all products of discourse. It only "evolves" through more permutations of discourse - like the endless spray of symbols in the occult posts.

Banksy, Christ with Shopping Bags, 2004, print

This explains why Modern literary greatness is based on manipulations of discursive forms and the representation of subjective consciousness. Standards always reflect the core principles of the frame of reference of whoever sets them. For Modernism, discourse is reality and individualized material lives all there is. These are the core principles. Atomized globalism that deliberately excluded any connection between literature and culture. Anything referential or aesthetic that tied the work to where it came from and who it spoke to. In other words, de-moralized materialism. Or the "Western" Tradition without the West.

Dogroll montage for CADAF NYC | Contemporary & Digital Art Fair, 2019

Deconstruction shreds Modernist ontological posturing - revealing it for the discursive mahjong that it was. Enter a new pretense - discourse is reality, so anything goes. So long as "anything" is de-moralized solipsism and incoherent devolutionary drone. Pretty much what anyone with a flicker of insight would expect from globalist-funded subjectivity where the only standards are the hatred of reality.

Here's where the inner consistency of reality matters. Modernist and Postmodernist arts do reflect the world as they define it. For the atavistic universalist, discourse and subjectivity is "reality". The Band had to shift ranges and move outside discourse altogether to sketch out what reality in the West actually looks like.

Jörg Breu the Younger, Free standing against the bar guard, from the Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica, compiled by Paulus Hector Mair, 1542, MSS Dresd.C.93/C.94, Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Dresden

The difference is that our account starts with what we can know and how we can know it and moves from there. It accepts the truth-value and limits of empirical observation augmented with logic and puts transcendent things where they belong - in the realm of faith and not rules for writers. It's worked out in numerous posts and summarized in the recap post - what matters here is the basic pattern:

Three pillars that correspond with what is epistemologically possible and logically necessary, and map on to the real historical development of the Western nations. This means that we know, experience, and express truth differently on different levels. The mechanical certainty of a steam engine doesn't apply to speculations about metaphysical origins. The Band calls de-moralized globalist materialism Flatland, since the whole ontological spectrum has to be pressed into the material. With horrifying results like discourse replacing culture.

Western culture is a continuum from Christian ultimate reality through Classical abstract thought into a material world known empirically. The Postmodernists were correct to dismiss the possibility of finding concrete metaphysicals in material human creations. But they were anti-human in forbidding those metaphysicals to be represented in the appropriate way. Tolkien reflects the internal consistency of a reality that is experienced imperfectly through observation and experience but reflects higher truths in a shadowy way.

George Inness, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1867, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Poughkeepsie, New York

Things that are metaphysically and empirically obvious - like the inability of evil to create or the healthful nature of organic cultures - are true in his worlds as well.

Here's the Band's take on literary greatness - an aesthetically compelling creation that is consistent with the fullness of reality and offers some insight into our place in it. The rest boils down to taste and judgment. There is nothing wrong with a good read, but a work has to have beauty, wisdom, and coherence to be truly great.

Donato Giancola, Huor and Hurin Approaching Gondolin, 2013

Tolkien vaults that standard with ease. Calling his immense Sub-creation a world sells it short. Legendarium gets used a lot and is a much better choice. A sprawling web of evolving tales in different modes with a consistent vertical ontology tied together by logos and bound by human limitations.

And what's the point of mapping the foundations of

the West if we don't use them to build ?

This post will make a case for the greatness of The Silmarillion as an extraordinary aesthetic creation that is perfectly consistent with the fullness of reality and offers profound insight into our place in it. To do this, we will be referring back to the vertical nature of logos, so one last reminder to check out the set-up if that doesn't make sense. We'll also weave in observations about discourse and secular transcendence in authorized culture when relevant. It can be difficult to break through the conditioning - the whole system is set up to make us feel helpless and dependent on things that are obviously false.

Brandon Schaefer, How to Paint a Sci-Fi Landscape in Space

Relativity is a perfect metaphor for de-moralized globalist "culture". In fact, it could be theorized into the philosophy of Postmodernism without any trouble. Atomized individuals with no fixed place to stand echolocating off each other as they float meaninglessly through a void.

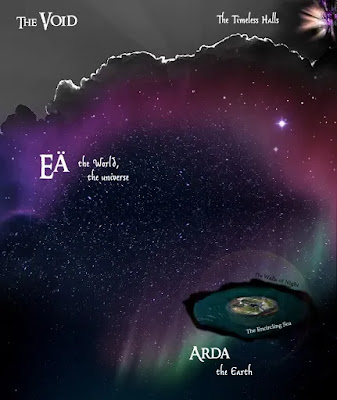

For Tolkien, the void is the opposite of creation.

He imagines a world in a universe of stars - not much said about them - with an unknown Void beyond. It's relation to the Timeless Halls, or ultimate reality, is unclear. As it must be to the limited representations of finite minds.

The point is that creation is the opposite of the Void. Creation is logos-driven - an act of order that pushes back against entropy. The only thing that does. The Void is the ultimate null state.

Culture and creation assume places to stand. Shared frames of reference and and assumptions about the world. These aren't philosophical absolutes because Flatland was just a story and philosophical absolutes don't exist in real life. This is what made Modernism so susceptible to the nihilism of relativity - relativity precludes the fake certainties of secular transcendence that modern rules depended on. But relativity itself was just another secular transcendence - one where the material "ultimate reality" was meaningless subjectivity. And this is just as ontologically incoherent.

Charles Euphrasie Kuwasseg, Scene in an Alpine Village, 19th century, oil on board, private collection

Culture and creation are real. Observable expressions of the interaction of Christian morality and Classical reason with the organic folkways and historical experiences of peoples. Which is why we find the nations down on the material level of our vertical ontology.

They, and their expressions, are historical realities - known empirically and historiographically, not philosophically.

Like Middle-Earth.

For all the information Tolkien wrote, he says little about the larger geography. We discover his world like a real one - through stories and histories. Including the limits and blind-spots that come with that.

The Silmarillion takes place in a relatively small corner of Middle Earth, and while there is lots of information about these lands, little is said about places where the action doesn't take place. The parameters are uncertain - like moving empirically into our uncertain material world.

We'll start with the Legendarium - Tolkien's true life work. The breathtaking scope of his imagination is one of the main reasons that The Lord of the Rings has such a powerful and haunting sense of depth when it is first read. That book is a finished novel, but it draws on the vast source material of Tolkien's evolving world. Including philologically-coherent imaginary languages. There are countless references to a mythic past that are very similar to cultural heritage in our own world. Snippets, but snippets that cohere into a glimpse of a past transformed by time into a mix of history and legend. As if Middle-Earth were real.

It reads this way, because the backstory was real - as real as a world history filtered through legend made up by any one author could be. The tales alluded to in The Lord of the Rings were "real" in the sense that they were written - they were existing sub-creations that followed the same internal consistency with reality that the novel did. They just came through in a different way, like the quasi-legendary past does. The Band called The Silmarillion the backbone of that world because it is the account of that legendary background.

This raises the first difference between the two books. The Lord of the Rings is a conventional novel. It's a trilogy divided into six "books" or movements, but the whole thing is composed as a single focused narrative involving a few protagonists. A unified plot with common motifs like the hero's journey and rightful king restored, the structure of introduction, crises and resolutions, climax and conclusion, and reliable narrative voice are all hallmarks of the novel form. The Silmarillion is really different - the way it plays with genre is something we'll get to soon. It is a book, but it is a stretch to compare it to a novel like Jane Eyre or The Lord of the Rings.

The Silmarillion as published is actually a collection of five different pieces, all written in different modes. There is an overall narrative that binds it together, but it is more world history than specific story arc. History in Tolkien's Legendarium is divided into ages - The Lord of the Rings takes place at the end of the Third Age and beginning of the Fourth. The Silmarillion spans the entire prehistory -from the Creation to the end of the First Ages, with pieces tying in the Second and Third.

The scale alone differentiates it from a conventional novel.

Enano Akd, Eru Ilúvatar and the Timeless Halls

The book opens with a cosmic creation story. We were serious when we said the entire prehistory.

Tolkien also conceived of it differently. When he first proposed it to his publisher as a sequel to The Hobbit, his intent was to frame it as a story-within-the-story. The idea was that this was a book of histories and legends that Bilbo recorded from ancient Elvish sources while in Rivendell. Elrond being from the First Age himself - the son of Eärendil and Elwing who rescue Middle-Earth from Morgoth. This gets rid of the reliable narrative authority that guides us through The Lord of the Rings, but it also freed Tolkien from the constraints of narrative form. The Silmarillion would be the 'what they could know and how they could know it' of that world.

J.R.R. Tolkien, First Silmarillion Map, likely 1926-30, single sheet, with two supplementary sheets not shown

Consider the legendarium that the The Silmarillion recounts. It developed over 60 years, with Tolkien often rewriting, rethinking, and evolving his creation in ways large and small. The basic concepts remain consistent, but the expression grows and shifts.

Exactly the same way that an actual cultural tradition evolves over time.

The internal consistency with reality applies to the entire legendarium on a structural level. The whole sprawling mass can be treated as a unified Sub-creation, both as a verb and a noun. Tolkien's creative process - evolving stories in different forms weaving together into a tradition - is how organic cultures form in reality. It's virtual folkways. And when we approach Tolkien's world through the legendarium, we experience it the way we do an actual culture - through a mess of histories, stories, and concepts that accumulate over time. There is no one fixed point that explains the whole thing.

Rescued medieval manuscripts from Timbuktu in 2013

There is no term for Sub-creation on this scale. But the haunting depth of Tolkien's books makes more sense when you understand that the world they express is a layered organic creation that conforms empirically to how real culture and history form. Not just materially, but epistemologically. We know the past through the historical record.

The internal consistency of reality rings so true - so familiar - because it mirrors what we can know and how we can know it.

It has the form of truth.

This raises the narrative connection between the legendarium and our world. Tolkien's original frame was that this was a was a collection of lost tales given to a Medieval Englishman by a mariner from the Undying Lands.

The Book of Lost Tales was Christopher's first foray into publishing his father's notes. It went on to become the first two books of the 12 volume History of Middle Earth. It includes Tolkien's earliest ideas about his world, including the mariner from the forgotten West frame story.

This placed the legendarium squarely in our world - a lost prehistory akin to Robert E. Howard's Hyperborean Age or the alien civilizations of H. P. Lovecraft. Tolkien never abandons that idea, and the passing of the Elves at the end of the Third Age prefigures the de-moralized, disenchanted materialism of global modernism. Most maps of his world look like early versions present-day geography.

Sampling of maps from a duckduckgo "map of Arda" search

The problem with thinking of the legendarium as the lost history of our world is that it is limiting. It clearly isn't our history, making it easy to dismiss as a flight of fancy. It makes more sense to think of it as a history that could have been ours. A world that could have been ours. That speaks to our world as if it were ours. That rings true as if it were ours. The internal consistency of reality.

Bringing us to allegory.

The Silmarillion is hard to classify because it is so unique. Tolkien insists that he is not writing allegory, although there are obvious allegorical elements in his work. He addresses this in the Introduction to The Lord of the Rings when he distinguishes between allegory and applicability.

First a note on allegory. The Band has used this term before, as a way of thinking through representations of a world that we can't access "in itself".

Noumenal reality in Kantian terms. That which is beyond direct conceptualization.

The graphic is explained in this post, if you are interested.

From this perspective, everything is allegorical to some degree. Even the things we see are lightwaves triggering neurological processes that can then be expressed through whatever media are available. This position is not that different from Postmodern subjectivity, except for the part where a reality perceived imperfectly is still a reality. It's just not seen clearly.

We needn't share the same impressions to demonstrate that those impressions reflect the same underlying reality in an actionable way. This common reference - and not our subjective impression of it - is "material reality". We can describe and classify this in terms of form and matter, and can even manipulate it to suit our needs. But we can't empirically observe what is beyond those impressions. That's above the material on the ontological hierarchy and only knowable through abstract logic and ultimately faith.

The subjectivity is obvious - consider a colorblind person or hallucinations. We have different sensory acuities, preconceptions, and grasp on pattern recognition that we communicate in persona ways.

On this level, everything is allegory.

But Tolkien was referring to a more specific definition of allegory. This version is associated with literature and found in the visual and dramatic arts as well. This is based on Classical notions of mimesis - the natural expectation that the arts represent things in an idealized or enhanced way that was assumed in the West. That literature has a plot.

A plot is the sequence of events that make up a narrative - what gives the story its coherent structure. Plotting is the basis of literary mimesis, and mimesis is the foundation of imitation in the literary, dramatic, and visual arts of the West going back at least to Aristotle.

Tolkien's Sub-creation is a mimetic process.

Mimesis represents reality, meaning that it is based on the experience of reality, but also changes it into something more structured and focused. Just think of how a story unfolds in a way that feelc realistic but has a meaning and order to the sequence of events that isn't found in real life. Millions of people practice with and look after guns every day in real life without incident - Checkov's Gun is is only a "rule" in the structured mimetic transformation of a plot.

Or in Tolkien's terms from the last post, images based on the world transformed by the imagination into an original creation with an inner consistency of reality.

It rings real, but isn't. It's mimesis, and it it's "unreality" can point to higher truth.

It is the structured, man-made nature of mimetic imitation that makes allegory possible. A narrative has the inner consistency of reality so it proceeds in a way that resembles a natural chain of events. But it isn't. It has a plot structure, where each detail is created to fit within this larger whole. By choosing details with secondary or figurative associations, the same structure can communicate a parallel, figurative message external to the literal story but carried by the same plot beats.

Temptation of Christ, 12th century mosaic, San Marco, Venice

The idea came from theology - thar Biblical passages transmitted meaning on levels at the same time. Theologians developed a complex system of figurative meanings, with allegory occupying one level. This exploded in medieval culture, where all sorts of things were given symbolic references.

Noah's a good example - 40 days and nights of Flood prefigure the 40 days and 40 nights of Jesus' temptation (Matthew 4:2) and the 40 days between the Resurrection and Ascension (Acts 1:3). This link has more Biblical 40s. This one looks at typology in Noah from an Orthodox perspective.

In literature, the distinctions between different levels of figurative meaning collapse into a single concept of allegory - what we described as a figurative narrative told through a literal one. It's a lot like metaphor - an "extended" metaphor is the easiest way to think about allegory. Metaphor stretched out into into a narrative or other set of coherent relationships external to the literal meaning of the story.

The simplest sort of allegory - the most obvious - is personification - a character or elements that embodies a concept in a story.

Dickinson's famous poem uses personification to give the literal meaning - a carriage ride - a secondary one about mortality.

Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress is a very famous example of a prose allegory made entirely of personifications.

The problem with personification is that it limits characterization. There's not much room for subtlety in someone called Faithful whose role in the story is to behave faithfully. When everything wears it's symbolic label, the allegory becomes so in-your-face obvious that it undermines the pleasure of the story. In fact it becomes impossible to really appreciate the narrative without the allegory, blurring the literal and figurative.

More complex allegory weaves the secondary meanings into an appealing story without being so overpowering.

Unknown Master, Florence, Allegorical portrait of Dante Alighieri, 16th century, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art

Pauline Baynes, illustration from C. S. Lewis' The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, published 1950.

Closer to Tolkien, C. S. Lewis' The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is this type - Aslan's death and resurrection as an allegory for Jesus' in the Gospels.

When Tolkien claims that he isn't writing allegory, this is what he is referring to. A clear secondary symbolic narrative that is communicated figuratively through the literal one.

Now consider this quote from the Introduction to The Lord of the Rings:

"... I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse 'applicability' with 'allegory'; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author. An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses from evidence that is inadequate and ambiguous."

This gets to the heart of Tolkien's vision. Allegory is too heavy-handed - the author trying too hard to impose a single symbolic interpretation interpretation on the readers. Applicability is more reader-focused - there are secondary meanings in the narrative, but they are insights that you find by applying the experience of the story to your own experience of the world. The mimesis is a representation of reality, so it is appreciable in real terms - it rings true. But it is also structured and focused, making it possible to see things that may be obscure in real life. So you apply its wisdom in any number of ways, rather than getting one preset allegorical take.

Paul DeMan, Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust, 1979

Keep in mind that no terms are perfect - this is the secular transcendence trap. These describe intention and direction, not mutually exclusive philosophical categories.

De Man was at the center of the Yale School and the most influential deconstructivist critic in literary history. His premise is that all language is inherently figural and therefore the distinction with literal is meaningless. It's all allegory. He's right on one level, but is trapped by his blind faith that academic discourse is reality. So he ignores the reader's share - the good faith attempt of the reader to make sense of the story in a personally meaningful way. De Man is a master of obfuscating jargon but is an embarrassingly - painfully - binary thinker. Partial meaning is beyond him. Look at the date - he's figuring out allegory and discourse a quarter-century after applicability rendered the issue irrelevant. Ladies and gentlemen, higher education.

Obviously Tolkien is allegorical in the Postmodern sense. Everything is. But he assumes a non-retarded reader who picks up a story with the intention of forming their own imaginative impression from the book. That is, meaning that is both based in the text and subjective at the same time. Because somehow readers can maintain distinctions between literal and figurative through their own acts of imagination despite the ontological fuzziness.

Poor De Man looking at the world is like a goldfish contemplating the universe beyond the bowl.

Someone should have tossed him a baseball.

When Tolkien claims to dislike allegory, he is explaining to the not-moronic that his story doesn't tell a parallel figurative one in a traditional genre way. He is sub-creating an imaginary history that has the same inner empirical and moral principles as ours. Just clearer. This makes them applicable to a wide range of contexts rather than a single allegorical message.

Kip Rasmussen, Túrin Approaches the Pool of Ivrin

We've see that Tolkien's Sub-creation is a mimetic act as understood in the traditional Western way - a limited human analogy to God's creation of the universe, or the ultimate creative act. This is exactly the same notion of artistic creation that the Band describes as a material-level manifestation of Logos. Tolkien's stories ring true because they reveal logos in a fantasy world where moral and logical distinctions stand out more clearly. Actions have consequences, and that people are their own worst enemy. The corruption of Fëanor isn't an "allegory" of the Fall because it doesn't represent the same narrative beats. But it shows the same pattern of vanity, greed, and pride bringing about a disastrous change of fortune with metaphysical consequences for the nature of our existence.

This is applicability. Not one symbolic meaning but a meaningful Sub-creation where each reader can find logos-based insight that applies to them or their relationship to the world. Insight from replicating real patterns in an unreal structure to see that which is obscured in muddy reality.

Coming back to the connection to our world, it is most accurate to think of the legendarium as a history of a world that could be ours. Not imaginary "literal" prehistory or traditional allegory but a mimetic sub-creation that echoes and is applicable to our own. And this is distilled into something almost scriptural in The Silmarillion.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo,1975; The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, 2009; Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, 2014; The Story of Kullervo, 2015

The breadth of the applicability comes from Tolkien's understanding of Western cultures. His linguistic skills were astonishing - according to one site, he knew Latin, French, German, Middle English, Old English, Finnish, Gothic, Greek, Italian, Old Norse, Spanish, Welsh, Medieval Welsh, and Esperanto, and familiar with Danish, Dutch, Lombardic, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Swedish and other Germanic and Slavonic languages. We see this in his translations and adaptations of historical tales. This gives his stories complex roots that can never be pinned to any one frame of reference.

There is a comparison with Athanasius Kircher, another creative polylinguist from our obelisk occult posts. Both used tremendous knowledge to constructe complex imaginary worlds. The difference is that Kircher was a luciferian fraud who pretended his inverted fantasy was real, while Tolkien was honest about his fantasy and used it to reflect on reality.

The connection between The Silmarillion and the legendarium can be seen in the five part structure of The Silmarillion.

The sections span the history of the world from the creation to the end of the Third Age - the full range of Tolkien's creation. And each one is written in a way that reflects the historical distance and ontological level that it is referring to. Read that last line again. Five texts referring to different aspects of coherent imaginary world that represent their subjects in the way that the same kinds of subjects are knowable to us in reality.

Alan Lee, Bilbo Baggins

This is applicability and Sub-creation down to the perceptual level - the narratives, underlying structure, and how we encounter them as a reading experience conform to how we understand out own reality.

World creation by simulating the way our history is known to us in reality was present in Tolkien's thought from the beginning. The framing story of a character reading manuscripts was there in the original idea of the visitor from Valinor and the revised concept of Bilbo writing in Rivendell.

Consider the five parts:

The first two tell of the creation of the universe and the first divine or angelic beings. We will start with the Ainulindalë (The Music of the Ainur) - and the striking opening that tells that we aren't in the typical world of fantasy.

There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they were with him before aught else was made. And he spoke to them, propounding to them themes of music; and they sang before him, and he was glad.

Anna Kulisz, Ainulindale

It begins with the creation of the universe by Eru - Tolkien's God - starting with a group of spiritual beings called the Ainur. The frame story is that this account was given to the Elves by the Valar - Ainur who entered into the world - not "as it really happened" but in manner that they could comprehend. This in turn reaches the ancient mariner or Bilbo who relays it to us. It's the echo of an figural transmission - like any metaphysical representation in a fallen material world.

This is consistent with a vertical ontology. The creation of the universe from metaphysical forces by ultimate reality is something that happens above the material - it can't be clearly represented to finite material minds. It has to be represented allegorically, with something that is comprehensible. A transcendent secondary narrative communicated figuratively.

The Ainulindalë is allegorical in the traditional literary sense because a creation story has to be. It is consistent with how metaphysical things can be represented.

Look how he does it.

First, the language is outright biblical in its lofty tone and sparse solemn phrasing. To the reader coming from The Lord of the Rings, this is a clear sign that we are in a very different literary mode. And consider the metaphor Tolkien uses for the creation - music as a symbol of the inherent order or logos of creation is as old as the West.

And it came to pass that Ilúvatar called together all the Ainur and declared to them a mighty theme, unfolding to them things greater and more wonderful than he had yet revealed; and the glory of its beginning and the splendour of its end amazed the Ainur, so that they bowed before Ilúvatar and were silent.

Anubis1000, Ainulindale V

We've seen it go back to the Pythagoras and the harmony of the spheres. The Band looked at music as a unique art form that combines pure logic - the mathematics of harmony - and pure feeling - wordless, imageless sensation that goes direct to the emotions. Here's the occult post.

"Then Ilúvatar said to them: 'Of the theme that I have declared to you, I will now that ye make in harmony together a Great Music. And since I have kindled you with the Flame Imperishable, ye shall show forth your powers in adorning this theme, each with his own thoughts and devices, if he will. But I win sit and hearken, and be glad that through you great beauty has been wakened into song."

The chorus of Ainur singing the world into existence with the theme of Ilúvatar is not an allegory of Genesis. It is an allegorical creation story that is conceptually consistent with Genesis - music as a metaphor for the Logos of God's creation. It is applicable because it offers insight into the nature of creation in the West, while being different. It is mimetic, a sub-creation responding imaginatively to the real world.

Kip Rasmussen, The Music of the Gods

The Flame Imperishable clarifies that the inability of evil to create is fundamental - inherent in it's nature. Tolkien has stated that the Flame is akin to the Holy Spirit. The divine energy of real creation that artists imitate imaginatively in their Sub-creations. It is the exact same path from human creativity to God's that the connects us to truth and beauty through Logos. Since evil is at heart a rejection of ultimate reality - truth, beauty, empirical observation - and a connection to ultimate reality is a condition of creativity, evil can't create.

The music metaphor plays the same role as well. Harmony expresses the beauty of creation - a divine act of order set against the entropy, appetite, ugliness that is the fallen condition.

The Ainur aren't exactly angels, but occupy a similar place between God and man. And their role in singing creation into existence provides the context for a Fall. Specifically Melkor, greatest of the Ainur, rebels against the themes of Ilúvatar out of pride and vanity. The desire to create on his own or be his own God.

But as the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Melkor to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of Ilúvatar, for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself. To Melkor among the Ainur had been given the greatest gifts of power and knowledge, and he had a share in all the gifts of his brethren. He had gone often alone into the void places seeking the Imperishable Flame; for desire grew hot within him to bring into Being things of his own, and it seemed to him that Ilúvatar took no thought for the Void, and he was impatient of its emptiness. Yet he found not the Fire, for it is with Ilúvatar. But being alone he had begun to conceive thoughts of his own unlike those of his brethren.

Satan and the Rebel Angels Cast out of Heaven

Melkor seeks the divine spirit necessary for true creation out of a vain desire to usurp the rightful place of Ilúvatar - God - in the cosmos. It is literally the same, self-erasing "do what thou wilt" be your own god garbage that keeps coming up in the occult posts. The archetypical Satanic inversion - rejection of ultimate reality for ultimate solipsism - has been the basis of evil since Lucifer played meteor.

Melkor isn't an allegory of Satanic pride, because his rebellion, like Tolkien's creation in general, doesn't follow the same beats as Genesis. The Silmarillion isn't telling the Biblical creation story as a secondary narrative told figuratively through a different literal one. It literally is a creation story - different from Genesis, but expressing the same underlying meaning. Just filtered through the Imagination and processes of Sub-creation.

Consider how Melkor is introduced - a creature of the greatest talents moved by the desire to create and populate empty space. On the surface, it doesn't seem so unreasonable. In fact, it can inspiring when an artist pursues their vision relentlessly. But it's this appearance of normality that clarifies an insight into reality that may not be obvious in the cosmic setting of the Fall of the Rebel Angels or even the arboreal sin of Adam and Eve.

The Music of the Ainur

Creation is an act of logos - it is the way humans serve truth, push back against entropy, and resemble the divine image they were created in. But Melkor isn't a "person" - the Ainulindalë is using the musical relationship between Ilúvatar, Melkor and the Ainur, and creation to represent the literally unrepresentable - the formation of the World within/by ultimate reality. The problem isn't the desire to create. The problem is the rejection of ultimate reality - of God and Logos - to do what he wilt.

Placing ambition and will over reality is the signature luciferian form of inversion but it is easily confused with more healthy stick-to-itiveness. Melkor clarifies the difference. You see his starting point stated bluntly, and then then watch what unfolds as that same passionate artist degrades into utter evil in a way that isn't narrated explicitly in the Fall of the Rebel Angels. And the link between the rejection of logos and the extremity of creative ambition is not spelled clearly in the story of Adam and Eve. Tolkien's sub-creation makes the continuum between solipsism - pride, vanity, self-idolatry, greed - and what we conventionally think of as "evil" in a modern sense obvious. We have to apply Biblical falls to our material existence, but Tolkien followed misaligned desire to its ultimate end.

Evil can't create because it rejects logos - it is left with what isn't truth, beauty, and the connection to divinity that is the very definition of creation

More applicability. Melkor does what self-idolators tend to do when their greed and vanity is thwarted - they lash out.

Anna Kulisz, Ainulindalë – The Discord of Melkor

Some of these thoughts he now wove into his music, and straightway discord arose about him, and many that sang nigh him grew despondent, and their thought was disturbed and their music faltered; but some began to attune their music to his rather than to the thought which they had at first. Then the discord of Melkor spread ever wider....

In the end Ilúvatar weaves all the music into the creation of the world, including Melkor's strife. In fact, the rebellion is revealed to be all part of the divine plan.

Jef Murray, Music of the Ainur

I am Ilúvatar, those things that ye have sung, I will show them forth, that ye may see what ye have done. And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite.

Map of Arda - the world - in what looks lihe the Second Age. It exists within Ea or space with the Void and Timeless Halls "beyond".

For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.'

Applicability continues when we see Melkor's response to Ilúvatar's revelation that his secret desire for creative autonomy was foreseen all along. Then the Ainur were afraid, and they did not yet comprehend the words that were said to them; and Melkor was filled with shame, of which came secret anger. Secret anger. Melkor isn't the Devil, but prideful rebellion against cosmic order is something they share. As is the link between the exposure of vain posturing and gamma rage.

Consider what is really being revealed to him that is so unbearable. That there is no creation "outside" of ultimate reality. It's all that can be. His desire is not just illegitimate and unjustified, it is impossible by definition. Insofar as Melkor can create anything, it is within the terms of ultimate reality, of Ilúvatar. Even his "discord" happens within Ilúvatar's music - the harmonic metaphor for the Logos of creation - and is turned to Ilúvatar's end. But when his delusion bubble is punctured by basic facts, his reaction isn't to learn but feel shame, which he transforms into rage rather than facing his own skewed appetites. And once he steps outside of music and into the world, all he can do is invert, debase, and shrink into Morgoth.

It's a choice...

PaulHectorT, Ainur; Eru Ilúvatar, Creator of Arda. Sergey Musin, Morgoth Bauglir & Hurin Thalion

So we are presented with a story of Creation and corruption that is not the same as the account in Genesis, but is consistent with its relationships between logos, harmony, beauty, truth, God, and reality. It rings true. And the lofty scriptural language is appropriate because that is how we encounter these origins in our world. Genesis does represent cosmic events in a language that we can grasp, even if the particulars are beyond us. We don't get exposition and extraneous detail - just a powerful solemn narrative voice declaring what is. The Ainulindalë gives us a Creation that is applicable to the reality of the Bible in the appropriate language. How we experience it in real life. The internal consistency of reality.

To sum up: the form and content of the story and line up with what and how we can know. The creation of the building blocks of the universe in a solemn, scriptural style. It looks like this.

The second part of The Silmarillion - the Valaquenta (Account of the Valar) - is also set in the mythical past but is less ontologically or historically remote and is written in a different style. It takes a major turn from the Biblical creation story by introducing something like a pantheon of "gods" in the mythological sense. Super-powered beings that oversee the running of the world. Tolkien brings a number of the Ainur into the world to rule over it and ensure that the themes of Ilúvatar come to fruition. The greatest of them become known as the Valar and the lesser the Maiar.

Kip Rasmussen, Varda of the Stars

The Valaquenta is a listing of the Valar and significant Maiar and their main attributes, as well as the enemies of the world.

The Great among these spirits the Elves name the Valar, the Powers of Arda, and Men have often called them gods. The Lords of the Valar are seven; and the Valier, the Queens of the Valar, are seven also. These were their names in the Elvish tongue as it was spoken in Valinor, though they have other names in the speech of the Elves in Middle-earth, and their names among Men are manifold. The names of the Lords in due order are: Manwë, Ulmo, Aulë, Oromë, Mandos, Lórien, and Tulkas; and the names of the Queens are: Varda, Yavanna, Nienna, Estë, Vairë, Vána, and Nessa.

Note the difference in style - the spare and lofty Biblical language has been replaced by something like a transcription of an older legends that you might find in a medieval compendium. This brings us closer to the idea of Bilbo recording ancient accounts from Rivendell because it reads like the sort of thing he would copy.

The shift from Genesis-type creation to mythology is a reminder that Tolkien isn't writing allegory. Allegories don't shift stylistic mode, "historical" distance, and ontological level midstream. But both are simulated historical forms that are applicable to our experience of our own past. Classical myths coexisted with Biblical revelation in the Middle Ages because the they were turned into allegories. The old gods and stories became symbols of ideas and concepts instead of "real" beings. The Silmarillion differs by representing the Valar as real in their world, but that's the fantasy aspect that is based on reality but transformed imaginatively. "On Fairy Stories" tells us Sub-creation adds unreal elements to sharpen insights. The change from what we might call a scriptural tone to a mythological one does mirror the difference between the two in actual history. The Valar being "real" within the narrative sub-creation shows us how Tolkien's applicability works.

Anna Kulisz, Valar - Manwe

Many Ainur descended, taking physical form and becoming bound to that world. The greater Ainur became known as the Valar, while the lesser Ainur were called the Maiar. The Valar attempted to prepare the world for the coming inhabitants (Elves and Men), while Melkor, who wanted Arda for himself, repeatedly destroyed their work; this went on for thousands of years until, through waves of destruction and creation, the world took shape.

Stefan Meisl, Melkor

The Valaquenta resembles real mythology when it blurs the line between the Valar as anthropomorphic beings and forces of nature. It is impossible to reconcile the shaping of the earth through cycles of creation and destruction with the image of Manwë on a throne talking to the Elves. Tolkien uses the Valar figuratively - like medieval allegories of classical gods - and as real in his world at the same time. It is easy to see the contest of Melkor and the Valar as a mythologized version of the geological forces that shaped the real earth. A way of accounting for the earth sciences within the terms of the Sub-creation. In other words, the Ainur to Valar narrative connects the "Biblical" creation of the universe to the secular history of Tolkien's day in a way that is not obvious to us.

Consider. We have the Genesis narrative and a bunch of information and inference about the way the natural world appears to work that we are told are incompatible. Secular and sacred. In an earlier post, the Band compared the Biblical account of the Fall to empirical limits on our understanding of the world. We used the widest possible concept of allegory as the common ground because the two frames of reference are so different that is is hard to even think of them together.

Those posts consciously avoided the existence of evil - the most obvious sign of the Fall - to focus on our relationship with the world. There's a remarkable overlap between the Fallen world as a valley of shadow seen as through a glass darkly, and an entropic universe of strange ambiguities and unknowable limits. Click for the second post. The same basic condition, just from perspectives so far apart that they seem opposite.

The Valaquenta uses the Ainur/Valar-Maiar to make the connection between the metaphysics of creation and the nature of the material world more obvious. Melkor's primordial Satanic rebellion is woven into the fabric of the universe through the Music of the Ainur. The Fall doesn't just change Melkor or the people he corrupts - it changes reality as well.

Giovanni Calore, Melkor

When he enters into the world, he is a willful force of evil like the Devil, but he is operating in a world that he already altered in its creation. That this is part of the divine plan doesn't change the observation that the Fall has a moral and a material component. Human and physical nature are different from an ideal state. We don't need to recap the human nature, but think of our blurry, finite experience of the world. How poorly designed we are for our environments compared to the animals. How everything not actively maintained rots and collapses.

Melkor as a character condenses the Fallen material world and Fallen human nature into a single figure. The physical and metaphysical woven together in the most fundamental way. In the Band's terms, Tolkien gives us the fallen/finite world in a single memorable image. Think about that for a moment.

Tolkien captures the willful nature of evil as an existent in the world and the corruption of man and nature in one connecting character. The Valar do a similar thing with the generative forces of our living world. And the clash between Melkor and the Valar over the shape of the world maps conceptually onto an empirical world that is both supportive and hostile to life at the same time. Likewise a moral world that boils down to Logos vs. inversion - the servants of the Theme of Ilúvatar vs. Morgoth.

The Valar and the Valaquenta also fit what we can know and how we can know it. They bridge the gap between Ultimate Reality and the material world in a way that makes the connection clear, putting them on the abstract level of our ontological hierarchy. As Ainur at the creation, shapers of the world, and physical characters, they show it is all connected.

The way they are presented is consistent with how we represent abstracts. The idea of divine sub-creators echoes the Neoplatonic concept of the Demiurge, or abstract creative force between the world and God. That is, the abstract Classical thought between Christianity and the nations in the West.

Like myth, the Valar express abstractions as characters, only in the Sub-creation, they are real. This creates a certain incoherence in their presentation but does that thing Tolkien says fantasy is supposed to do. It clarifies something - in this case, the connection between the Creation and Fall and the empirical and social worlds that is hard to see. The Band took two posts to even try and spell it out. Writing this post, we realized that Tolkien saw the same thing - just articulated better in a different medium. We can't explain applicability any better.

And it doesn't stop here either. Because the Sub-creation is a history.

Fallen Angel wallpaper

For modernist reference collectors, the Valaquenta also brings the War in Heaven in the Ainulindalë into the material world, recast as a clash within a pantheon.

This where Tolkien comes closest to Milton - both use the fallen prince of angels to demonstrate the fundamental errors at the root of evil that repeat over and over through history. But while Milton shows the distortions of fallen perception, he doesn't embody the essential sameness of the fallen human and material worlds. Melkor weaving discord into Creation or as a dark titan smashing mountains and battling the gods makes the connection impossible to miss. The link between Satan's primordial rebellion and fallen human experience is made concrete.

We also learn that Melkor's evil is infectious - he corrupts a number of Maiar to his service like Satan's fallen angels. These include Sauron - the principle antagonist in The Lord of the Rings - and a number of others that are transformed into balrogs or demonic spirits of fire. Evil can't create. It can only mock and pervert with increasing ugliness.

thylacinee, The Balrogs of Morgoth

Bringing Melkor into the world physically is an example of how Sub-creation can simplify and clarify themes that are less clear in the real world. We have to see Satanic inversion and secular transcendence through the fruits - the lies and their consequences. The pride, vanity, and do what thou wilt solipsism are abstract evils that exist internally and are only externally visible through experience. Melkor gives the ontological degeneration that comes from choosing to rule in Hell over serving in Heaven visible form. The self-destructive abstractions become obvious when they are performed by a vile creature whose own stature dwindles and his depredations grow.

To sum up: the form and content of the story and line up with what and how we can know. How abstract forces transfer to material reality in a form reminiscent of real-world mythological accounts. It looks like this.

The largest part of the book is the Quenta Silmarillion - the main story that comes to mind when people mention The Silmarillion. It is much to long to analyze the way we did with the earlier parts, but there are some important themes to consider.

First, the narrative mode changes again - the Quenta Silmarillion reads more like epic history in prose rather than conventional novel, Biblical language or compendium account. But unlike the Ainulindalë or Valaquenta, the tone also changes over the course of the piece.

Murgen, Destruction of Illuin

We start with an extension of the theme of the Valaquenta - Melkor and the Valar battling over the shape of the world. The same mythic blend of narrative character-gods and natural forces that visualizes the link between physical and metaphysical. The Band calls this vertical logos and conceptualized it graphically. Tolkien saw the same thing and expressed it through narrative. Our way is easier to see at a glance, but his way adds the dimension of time. Narratives set the concept in motion.

Helge C. Balzer, Turin and Glaurung

As the Quenta Silmarillion unfolds, the tone changes into something closer to epic history in prose form. Mixed media, to be more accurate, because Tolkien was a fine poet and adds lyrics and verse to his stories. But more "realistic" in the sense of easier to visualize in real material terms.

This is where Tolkien's background in medieval history and literature really shines though. He doesn't try and copy the style of a real medieval chronicle or history - that would seem a bit precious. What he does is much more profound - he structures his piece in the same way as high medieval history was put together. Medieval histories often stretched back into mythical time - combining Biblical, mythological, and historical things into a single chronology.

Brutus arrives in England and slays the giants of Albion, from MS. Harley 1808 fol. 30, British Library

The idea with the myths was that they were distorted versions of real history. Like the first king of Britain being Brutus of Troy, a descendant of the Homeric hero Aeneas, who was in turn the son of the goddess Aphrodite.

Tolkien, like medieval history, blends the mythic and historical instead of treating them as completely separate things. The main feature of what the Band is calling epic prose, or mythic history is how the narrative starts in a dim and legendary past and becomes more prosaic as it moves closer to the present. This makes sense epistemologically because these histories were built out of older texts and accounts and these tend to be more precise and reliable the nearer they are in time. The further back you go, the more iterations and transitions the stories have gone through, and the less distinguishable they are from mythology. Internal consistency with what we can know and how we know it on the structural level.

ivanalekseich, Illuin (Spring of Arda)

Arda starts out resembling the Biblical account of the world - a flat plane protected by a firmament or dome. The landmasses of Valinor and Middle-Earth are separated by an ocean and surrounded by another. In the beginning, the Valar lit the world with to colossal lamps - Illuin and Ormal - until Melkor cast them down, plunging the world into darkness.

The Quenta Silmarillion doesn't read like a medieval history or epic, but it is structured like one. This lets it continue the move down the ontological hierarchy as we move closer to the present that started in the Ainulindalë. It begins on the mythic level - primordial clashes between Melkor and the Valar in the Valaquenta and fantastic things like the huge lamps that lit the early world.

But as the story progresses, it moves steadily to more "human"-level narrative. The accounts of the Elves and Men read less like the uncertain mix of story and metaphysics in remote mythic history and more like how medievals treated for the less distant past. Stories of the Valar include metaphysical aspects that are beyond the purely material discernment of Elves and Men. These are not as clear - say less "realistic" - than the later chapters which narrate material experience in material terms.

Stefan Meisl, Minas Tirith upon Sirion

The change in narrative style mirrors the change in ontological level. We've come from ultimate reality into abstraction and are now moving fully into the material. Lofty Biblical-type language for the Creation, mythic language for abstraction, and now historical epic for the material.

In the Band's terms, Tolkien uses forms internally consistent with how we know to offer insight into what we can know.

The challenge is to plot the gradual withdrawal of mythic elements in a narrative sub-creation where the gods are real. We will consider some main points on this journey.

First - consider how Melkor is changing. His descent starts with excessive ambition but when frustrated by his own limits, turns into atavism. The desire to rival the creator becomes the desire to oppose the creator. If he can't make his own, he'll tear down yours, rather than admit you surpass him. By the time he comes into Arda, he is a force of destruction - pure evil as the pure opposition to Logos. Using a character as both a person and a concept - physical and metaphysical - connects the abstract and the personal in direct way.

Silinde-Ar-Feiniel, Utumno

Melkor's evil isn't caused by his evil acts - the evil acts are symptoms of a more fundamental misalignment. His actions are consequences of an opposition to Logos. They're tells. When he builds Utumno, he is building his own Hell. And lashing out because pride-driven delusion collides with reality happens all the time. It basically is Postmodernism.

By their fruits...

After the destruction of the Lamps, the Valar wage war on Melkor, destroying Utumno and imprisoning him for three ages. This purges much of the evil from the world and prepares the way for the peak of Valinorian civilization and the coming of the Elves. The Two Trees restore illumination with a living light so beautiful and hallowed that it aestheticizes experience. This is the Noontide of Valinor - the zenith of a society of gods and spirits freed of the embodiment of evil. But not really.

Frédéric Bennett, Telperion Goes to Sleep, Laurelin Awakes

Golden Telperion and Silver Laurelin alternate casting the world in light. The change-over period was a magical time when gold and silver mingled.

Consider Valinor under the Trees. The Two Lamps lit the entire world - we don't get the sense that there is a metaphysical difference between the land masses of Arda. But if the Legendarium is to be applicable to our world, it has to reflect an ontology where the abstract and materially are different. Connected, but not in directly visible ways. The Quenta Silmarillion begins the process of dividing Arda into something closer to a physical and a spiritual reality.

The Two Trees of Valinor

In the sub-creation, "real" narrative things are applicable to clarified metaphysical insights, so the division is shown physically in the fantasy world. Valinor is lit by the Trees, but surrounded by fortified mountains that block the light from reaching Middle Earth. Middle Earth is separated by by a wide ocean and terrible wasteland of ice - a vast, twilight wilderness lit only by the stars. And even though Melkor was captive, evil was present here, if quiescent.

Melkor's Maia lieutenant Sauron secretly maintains his secondary fortress - Angband - that wasn't destroyed when the Valar came for him. The Valar are fixated on their Tree-lit paradise and ignore Middle Earth except for the hunter Oromë who journeys them to kill creatures spawned by Melkor.

We can see the outline of a metaphysical division in the emerging split between Valinor and Middle Earth. A star-lit wilderness marred by evil sums up Tolkien's vision of the material world. Breathtaking haunting beauty that inspires the deepest passions and inevitable ends with decline and death. From this angle, immortal lands of exquisite beauty hallowed by embodied abstractions hint at the spiritual and creative potentials of our higher nature.

Kip Rasmussen, Orome Discovers the Lords of the Elves

Tolkien makes it evident that they do feel a pull to the Undying Lands. Immortal themselves, and close personally to the Valar, it is clear that this is where they "belong". But they are also understandably attached to the wild starlit beauty of the world they awoke in, and many don't answer the Valar's call.

If we think about the two realms as applicable to spiritual and material natures, the Elves act out the oppositional pull of the two. As Middle Earth is increasingly distanced from Valinor, the Elves who stay diminish. Devolving in stature and power into something like the fairy folk by Tolkien's day. Following the application, becoming ensnared by the beguiling but spiritually empty beauty of the material world distracts from our spiritual natures. It is an enchantment. A glamour. A dead-end path to self-erasure.

Aronja, The Trees Of Valinor

Meanwhile, the Elves who journey to Valinor are bathed in the light of the Trees and reach their full potential. The lords of the Vanyar and Noldor become nearly god-like themselves. Following the application, think of them as turning from the material to the spiritual, only narrated in the sub-creation.

Which brings us to Tolkien's Elves and the insight they open into the two-sided nature of art and creativity. There are a few pieces here. The Elves are a critical part of Tolkien's sub-creation, both within the narrative and for the larger applicability. In the story, they are physical beings, human in form, though taller and more slender on average, and far more beautiful. Disarmingly, and sometimes enchantingly so. They are also far more capable - immortal from natural causes, stronger, faster, more durable, and able to wield considerable magical and artistic forces. In The Silmarillion, the great Elves approach Maiar in power.

The Halls of Mandos

The Elves are physical, but they have a different relationship with the world metaphysically. Men are short-lived in this world, with souls that depart Arda entirely after death. What happens then, the Valar either didn't know or wouldn't say. Elves are immortal and possess "spirits" rather than souls in the human sense. If they are killed, their spirits reside in the Halls of the Vala Mandos, from where they can be reborn.

But the immortality isn't unconditional. As the world evolves, Middle-Earth becomes the "mortal" lands, and Elves that refuse to move to the Undying Lands of Valinor dwindle and fade over time. Eventually devolving into the dimunitive, juvenile "fairy folk" that Tolkien viewed with some distaste.

Clearly, adding the Elves between Man and the gods in the history of creation doesn't line up with the Biblical account. It's a bit closer to the different races in Germanic tradition, but there is nothing in that history or literature like the Elves either. This is another reminder that Tolkien isn't writing allegory, but sub-creating an applicable fantasy. The question is, how do we apply the Elves?

Elena Kukanova, Return

Tolkien made a passing remark in "On Fairy Stories" calling the power of imaginative creativity - that is making illuminating sub-creations with the inner consistency of reality - Elvish. The sensitive imagination - the artist - is pulled between the beguiling beauty of the material world and the higher principles of the abstract or spiritual. Creators are at their most "Elvish" when their imaginations engage with the world to express higher truths. They start in Middle Earth, but have to choose the turn to Logos to really go anywhere.

Finrod Felagund was the finest of the Noldor in Middle Earth - a harpist, warrior, and Elf Lord who was closest to Men. He sacrifices his life to keep an oath to save the hero Beren and is untouched by the crimes of Feanor and his sons. We are told that his time in the Halls of Mandos was short, and he was reborn quickly and reunited with his beloved in Valinor.

The Quenta Silmarillion focuses on the Noldor like Finrod - the middle of the three tribes of Elves and the most gifted smiths and artisans. Unlike the lordly Vanyar or seafaring Teleri, the perfect group to illuminate the nature of art. The Noldor are closest to Aulë, the smith of the Valar, who teaches them the arts and crafts.

nahar doa, Aulë, Father of the Dwarves

Aulë clarifies the applicability. He's a Vala like Melkor so he has that same combined metaphysical-physical nature that makes him a character and a connection to Logos. He shows the importance of choice. Aulë created the Dwarves - beings that weren't "Children of Ilúvatar" but were the first sentient race in Middle Earth. This contravened Ilúvatar's plan that the Elves come first - like Melkor, Aulë put his own creative ambition over the divine plan. But what matters is the response.

Aulë accepts that he has wronged and prepares to destroy his beloved creations. At which point Ilúvatar is moved and spares them - they just have to sleep until after the Elves awaken. It is the exact opposite to Melkor's petulance into rage spiral. Aulë accepts the divine order - he subordinates creative ambition to logos. To reality. And the result is true creation. He is able to bring his masterpiece into existence - something original from the material of the world and not a corruption of something already there.

Tolkien shows us that creative drive isn't black and white. An artist needs fire and ambition to martial their powers and shape the stuff of the world into something beautiful or profound. The question is whether they align their visions with truth, or if they descend into solipsism and serve lies. The Band has sketched out the basic premise of the arts of the West - the expression of truth through beauty in material media. Tolkien is doing similarly.

Fëanor and the Noldor bring the applicability of the Aulë/Melkor choice - logos or luciferian solipsism and ontological ruin - from the abstract to the material level of reality. At least as far as the Elves themselves apply to creative potential in the real world. It makes it applicable to us.

Arcalme, Fëanor's heraldic device based on the design and description of J.R.R. Tolkien

Fëanor is the greatest of Elvish artists - the greatest artist to ever live. He perfects the craft of making flawless crystals and gems with beauty and other properties we can think of as supernatural. His masterpiece are the Silmarils - three clear gems of surpassing perfection, each containing some light from the Trees. These are the most beautiful and enchanting things ever made.

And they make for some interesting insights.

breath-art, Fëanor and Silmarils, digital art

Consider the nature of Fëanor's creation. He doesn't create in the manner of the Valar - transforming the earth and generating species. He takes materials already created and reconfigures them into something more beautiful or more profound.

"On Fairy Stories" gave us the term for what he is doing:

He is sub-creating.

Remember - narrative events are applicable conceptually. What is a Silmaril? Literally, an imperishable crystal containing the living light of the Trees and hallowed by Varda. Look at it in terms of applicability - it combines higher, abstract, spiritual essence with a material form of the greatest artistry.

That sounds familiar...

When the Band started looking at the art of the West, we identified a concept of art in ancient Greek thought that had value beyond that context. This was the combination of episteme - higher principles - and techne - refined artisanal skill. The come together in phronesis - principled creation.

As an concept, art is the combination of Truth and materials. Or what the Silmarils are in the applicational narrative

Click for the post on the episteme + techne = phronesis formula, and how it aligns with the vertical logos that defines the West.

.

The Silmarils illuminate the nature

of creativity in the West.

Consider how the ontological hierarchy - the chain of logos manifesting on different levels of reality in the appropriate way - is represented in the sub-creation up to the making of the Silmarils.

In an earlier post we visualized how how this notion of art maps onto the linked hierarchy of Western ontology. Here's the summary, click for the link.

Tolkien traces out a compatible relationship in the plot of his sub-creation. It's just narrated figuratively instead of visualized conceptually. You might say it's applicable. Here's what it looks like graphically:

First the chain of vertical logos from Ilúvatar to Fëanor

The world is created in Logos, but here is no Jesus - yet - in Arda, so Logos is expressed in the pre-Christian Classical metaphor of music. The Fall is captured by discord. Like the Old Testament, the world has a divine order that is unclear from within. A valley of shadow seen as through a glass darkly. This means Logos manifests differently on different ontological levels.

The Valar serve the music - they bring Logos through abstraction into the material, where Fëanor and the other craftsmen apply the teche to create phronesis. In the narrative, the Silmarils radiate this pure light of Truth into a Fallen world with miraculous consequences.

This is a really remarkable narrative structured along two axes - temporal and ontological. Mapping metaphysical relationships and how we know the past at the same time:

We can even get fancy and map a third axis on - the historiographic - or how we know the temporally and ontologically distant:

The Band also has a higher estimation of Tolkien's intelligence than most.

The idea that the Elves within the plot are applicable to the creative imagination outside of it is supported by how they react to Melkor.

Kenneth Sofia, Hosts of Angband

The inversion of the Elf is the Orc. Melkor attempts to create his own creatures like Aulë's Dwarves, but can't because he is evil. Detached from Logos.. All he can do is corrupt and pervert existing things into the opposite. Like Maiar into Balrogs. The Orcs are captive Elves twisted into their opposite - brutal, simple, atavistic monsters of animal appetite. Everything that the Elves, with their refined beauty and spirit of imaginative creation aren't.

The applicability gets clearer when Men appear in Middle Earth. The reader gets a direct proxy when an actual human perspective within the narrative opens up. Two things jump out at once - mortality and potential. The fact that Men die so quickly on a historical time scale severely compromises their understanding of the world around them. And despite this, they have the ability to be rival the grandeur of Elves and the cruel atavism of Orcs. In the Quenta Silmarillion, Men war with Elves and Orcs - a nice way to express the animal and spiritual sides in all of us.

Jenny Dolfen, For Maglor slew Uldor the Accursed

Note that the decision to align with and learn from the Elves or turn to the vicious appetites of Melkor doesn't change Men racially. Evil men don't become the equivalent of Balrogs or Orcs - they're just evil Men. Tolkien is showing us that narrative events in the sub-creation are applicable to morality and metaphysics in human reality - in and out of the fantasy.