Something different. A close look at a tremendous 6th-century monument to the good, the beautiful, and the true that lays bare the myths of progress while showing that the serpent was always in the garden..

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction to the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and other topics have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check regularly and it will be up there.

One of the canaries in the coal mine for the collapse of Western civilization into the beast system and its House of Lies was the degeneration of art. The Band’s arts of the West posts have been slowly tracing this process from the ancient past – we’re in the late Renaissance now and have no idea how long the journey will take. If we could post more frequently…

Anyhow, the nature of the journey isn’t just slow. It’s also big picture, meaning we can only look at some big themes and not go into too much detail about specifics. This post is different – an in-depth look at a remarkable monument that hasn’t gotten its due. Think of it as a cross between the arts of the West and a Truth of Culture post. A focus on one noteworthy thing but something historical instead of more recent culture. That would be the incredible 6th-century church of San Vitale in Ravenna, the most impressive of that Italian city’s impressive collection of early Christian monuments. And typical of a Truth in Culture post, we can use the close look to make some larger observations.

Everything about San Vitale screams quality and care in the pursuit of beauty for the glory of God. Even the floors are works of art - like this mosaic of fine marbles and tilework.

This is what you walk on...

Here’s one larger observation – before art could be jacked and inverted it had to be isolated and cut off from culture. This is the demented “autonomy” we’ve mentioned in earlier posts.

Maurice Denis, Sunlight on the Terrace, 1890, oil on... who cares.

Consider this quote from French supper-hack Maurice Denis from 1890 - "a picture, before it is a picture of a battle horse, a nude woman, or some story, is essentially a flat surface covered in colors arranged in a certain order."

The correct response was who? Or perhaps who cares? But the slow corrosive drip of cultural entropy rotted the entire abscess of modernism out of these humble beginnings.

The idea that art has no purpose or definition other than being art. Self-deifying morons leapt at this because it promised to free them from coercion and control of academies and elite clients like aristocracy and church. The reality was that in one swoop it wiped out the entire historical set of purposes and references that justified and supported the arts from the jump.

Look at me! I can scribble on a page and no one can say it’s not art!

Wait a minute… That do what thou wilt’s music!

Max Pechstein, Young Woman with a Red Fan, 1910

Everything about this is aggressively ugly. From the clashing garish colors to forms that look like they were cut from cheese.

Of course, autonomy was an extreme position. What happened was that into the 20th century any retarded "movement" could declare what art "should be" and scribble and splatter accordingly. Here's a decent piece written from within a beast system framework that covers the contextual range of meaning connected to autonomous art.

Two main problems.

1. “Freedom” doesn't exist.

The Band’s pick for most misunderstood concept ever. You don't have to accept Maslow as the last word to see there is no “freedom” in a world where we are dependent on things for survival. Especially not in a complex social structure involving the cooperation of countless stakeholders. Freedom is an abstract concept that can only be relative in material existence. Freedom from something.

A societal structure like “art” can’t be free because it depends on societal entities for support. So art can only be free from some faction or another. And since it can’t be what they claim… ding ding ding liars!

2. Art is a societal structure or space.

Horace Vernet, Julius II Ordering Bramante, Michelangelo, and Raphael to Build the Vatican and St. Peter's, 1827, oil, Louvre

Art has no intrinsic identity outside of man-made rules. Even stating that it exists autonomously is an act of creative definition. Someone will always be driving the making and consumption of art. The real meaning of modern autonomy meant kicking out the old arbiters of quality and replacing them with the new definers – the critics then academics of the modern beast art world.

The old authorities wanted certain things from their art – quality, meaning, etc. The modern beast system was in the early stages of tearing culture down, and so would squander resources on the opposite. It was “autonomy” that reached the peak in the idea that art has to be meaningless and not represent anything. Then that became not representing anything connected to beauty, reality, or tradition. When “postmodernism” restored the idea of meaning, the chain was broken.

The redefinition to inversion process is something we’ve covered in detail elsewhere. Click for a post.

Jeff Koons, Three Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (Two Dr J Silver Series, Spalding NBA Tip-Off), 1985, Tate London

Postmodern art reacted to the absurd seriousness and autonomous claims of modernism by reconnecting with reference. Whether reference to tradition, politics or culture. But it's reference without beauty, truth, or skill. Just hackwork to launder money while further degrading the cultural fabric.

Something like this is easy to disdain. But actually think what is says when enormous financial and cultural resources are expended on pretending this is worthy of... anything. Trite appeals to the Emperor's New Clothes or the like can't scratch the surface of the civilizational suicide across all cultural and intellectual levels.

Ironically the path to redefinition-inversion of art into Art! began with the formalization of the arts in the Italian Renaissance. Ironic considering the towering genius associated with that era. But this is where the arts were first defined in critical terms instead of cultural convention or client desires. And defining the arts as a thing apart was the first step to isolating, jacking, and inverting. If art is merely a culturally-determined mode of expression, it's too broad for a sociopathic cadre of freaks to control then pervert. But turn it into a niche ghetto? It's the same process that happened across Western culture in the 20th century.

In the Renaissance, painting, sculpture, and architecture were singled out as uniquely worthy of liberal arts status as "art". This allowed them to be granted the prestigious "theoretical" designation. And that was the first step to the small cadre of critics and experts taking over.

The Mona Lisa, the David, and Brunelleschi's dome are masterpieces. But they drew arbitrary limits over Western art and tied definitions to self-declared elites.

The Band defines art as a process or relation and not as a set of universal rules or institutions. Logos + Techne or L+T. It’s connected to our understanding of the basic nature of reality, but it’s not necessary to go into that to give a working explanation [click for a post if interested in exploring further]. We've recognized that art is difficult to define because it is one of those concepts that brings together levels of reality in a composite creative act. It is skillfully crafted material but material skillfully crafted with the intention of visualizing some form of higher truth. This could be truth about people, society, or nature, but at its peak there is something of the divine. Truth with a capital T, manifested materially as beauty.

We've also recognized that art has appeared in almost every time and place. It's far too broad to bind to narrow rules of imaginatively constipated critics. L+T doesn't specify what truth or what skillful making, but leaves that up to specific artist and culture to determine. It looks like this.

Art has to have an element of technical skill and connect to truth in some manner. That’s it. It can be painting, sculpture, and architecture. It can also be tapestry, mosaic, digital art, collage, stained glass, metalwork, etc. Just Logos and techne as culturally preferred.

But that rules out almost all the official Art! produced since the dawn of modernism.

Alexander Ignatiev, Beams, oil on canvas, 21st century, private

There are still plenty of real artists today. They just work independently, and outside of the official beast system. .

The Band's L+T definition recognizes that art is human cultural activity and will take different forms in different cultures. Something like the mosaics of San Vitale don’t fit into the beast concept of Art! - the mosaics aren’t painting or sculpture, the subject matter is overtly Christian, and the whole thing gets its impact from the assembly of pieces working together. It doesn’t conform to the ‘fits in a gallery controlled by sociopaths’ model. But it does fit L+T.

The mosaic interior was the preferred form of high status decoration in early Christian Italy. It’s certainly high technical skill. And it drips logos – the pieces together place you in a dazzling experience of God’s grace. There’s even some aristocratic inversion. In short, a tour de force of aesthetics and history.

San Vitale was completed in 547, placing it at a tumultuous time in Italian history. The Western Roman Empire had fallen and the last emperor Romulus Augustus deposed by Odoacer in 476. Odoacer had in turn been deposed and executed by Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths and founder of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in northern Italy.

His capital was Ravenna – an important late imperial city and last capital of the Western Empire after Rome became unmanageable. Theodoric was a smart administrator and balanced the differnign customs and beliefs of his Arian Christian Ostrocothic and Orthodox Christian subjects. He even maintained parallel legal systems.

Arianism was a branch of early Christianity that rejected the full divinity of Christ and the concept of God as a Trinity. It was declared heretical at the Council of Nicea in 325, but lingered in some areas - especially the Germanic tribes - until as late as the seventh century. Theodoric and his Ostrogoths were mostly Arian, but the majority of his Roman subjects were Orthodox. By allowing both to flourish let him keep the peace and enjoy widespread support.

Ravenna contains monuments with Arian and Orthodox characteristics – evidence of the unusual coexistence under Theodoric.

The Baptistery of Neon or Orthodox Baptistery was built over the 5th century. The Arian Baptistry was built by Theodoric in the early 6th century.

Like Charlemagne several centuries later, Theodoric saw his people as culturally backwards compared to the Romans. He worked to “enculturate” the Ostrogoths with classical learning and impressive late antique-style architecture. Civic harmony and good relations with his Roman subjects facilitated this and made Ravenna the jewel of the West for a time.

The Mausoleum of Theoderic, built around 520, Ravenna

Theodoric was buried in a round monumental tomb after Roman custom. The style and stonework is Ostrogothic. The hybrid structure is a perfect metaphor for the way Theodoric's rule spanned two worlds.

All things come to an end, and the Ostrogothic Kingdom collapsed under Byzantine invasion and conflict with the northern Franks. The Byzantines were the main cause – the Emperor Justinian had hoped to reconquer the lost Western territories and plunged the Italian peninsula into a horrible wasting war. While ultimately victorious, the Byzantine triumph was short lived. The Lombards exploited the weakness of a ravaged Italy and invaded from the north, bringing another wave of misery and strife. This was the context that led to the founding of Venice that we discussed in an earlier post.

Ravenna was left as the jewel of early Christian architecture and art. Late Roman, Ostrogothic and Byzantine constructions coexist in the finest collection of building from this era anywhere. And of all these monuments, S. Vitale is the highlight.

Some fortuitous history is involved – Ravenna was a major center in the 5th and 6th centuries but sort of fell off the map after that. Without the steady growth and redevelopment of places like Milan or Rome, the core of late antique buildings wasn’r redeveloped.

The church itself was begun in 526 by Bishop Ecclesius under Ostrogothic rule and completed in 547 by the Byzantine Bishop Maximian. It commemorates a local saint of historically questionable origins who remained popular through the political changes. Construction was financed by a wealthy local banker so funds were no object. The long construction time probably includes delays caused by the Byzantine-Ostrogothic Wars.

Aerial view of San Vitale with the small fifth-century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in the immediate foreground. The tower was a later addition.

San Vitale stands out for it's shape. It is centrally-planed, meaning it is designed symmetrically around a central point and not a longitudinal basilica like Old St. Peter's or the other early Christian churches in Ravenna. For contrast, the Basilica of Sant' Apollinare in Classe - another Ravenna landmark - is contemporary with San Vitale but laid out like a traditional basilica. It was started in the early 6th century and funded by the same banker - Iulianus Argentarius - and consecrated by Bishop Maximian in 549.

San Vitale is different, a two level centrally planned octagonal structure with a taller domed central area surrounded by a two-story walkway or ambulatory. Originally only the roughly 90’ diameter central dome was vaulted while the surrounding ambulatory having flat timber trussed roofs. It's easier to show than explain.

San Vitale in plan with a photo of the upper portion.

The building consists of concentric octagons - the lower being the outer ambulatory and the upper the domed core. The two are connected by columned exedra or curved spaces between the supporting piers of the dome. The apse breaks the symmetry and provides the ritual focus. A narthex is just a porch. The ambulatory vaults indicated by light dotted lines were a later addition,

The complex floorplan isn't discernable from the outside. Here, the octagonal geometry is more clear.

Looking at San Vitale today, the big flying buttresses stand out. These were added in the 12th century for extra support when the ambulatory was vaulted. Vaulted construction is heavier but channels the additional force down onto the supporting elements. This also includes lateral force vectors that push outward. The original walls weren’t designed to hold up to this so the buttresses – a Gothic building technique – provided the stabilizing counter-thrust.

View with two of the external buttresses. They push against the wall opposite the points where the lateral thrust of the roof vaults pushes out. This prevents them from toppling the wall and locks the structure together.

Early Christian exteriors are deceptive by design - hiding the inner splendor behind plain exteriors. It is true that San Vitale's polygonal shape makes it somewhat interesting from the outside, but there is no superfluous ornament. Older classical architecture was outwardly splendid because the public didn’t have access to the interior. The inside of a Greco-Roman temple held a cult statue but was restricted to the priests and privileged VIPs who administered the rituals. The public was addressed outside and experienced the temple as a god’s house. A special structure that stood out from other buildings with its classical orders and carved reliefs.

This recreation of the temple of Venus and Rome in imperial Rome shows the difference between the outward-oriented decoration of a classical temple and the plain exterior of an early Christian church like San Vitale.

A church was different from a temple because the whole congregation was active on the inside. Christianity defined itself in antiquity as set apart from the everyday world. It became prominent relatively late on the imperial scene and grew by attracting converts away from the traditional worldly focus of Roman life. A plain outside and splendid interior symbolized the personal journey to Christianity as inward focused and distinct from regular life, just as the religion prioritized salvation and the soul over worldly pleasure and fame. Entering a church meant leaving the ordinary material existence for a special place of spiritual wonder. An interior journey that visually called to mind the indescribable wonders to come in the Kingdom of God.

S. Vitale is a perfect example of this. The plain brick exterior does show the complex construction but had minimal decoration and no color. There is nothing to hint at the splendor that awaits beyond the door.

This hasn’t changed, regardless of what the narrative engineers of the House of Lies say.

S. Vitale starts with the complex plan. It’s an octagon surrounded by openings instead of straight sides or walls. Seven of the openings are exedrae - semi-circular concavities – and the eighth a rectangular sanctuary & apse. The apse extends through and past the ambulatory. It's easy to see in this aerial and cutaway view below.

This view shows the concentric octagonal shape very clearly. It's centered on the sanctuary and apse - the apse of the semi-circular projection at the bottom of the upper picture. The raised area in the outer ambulatory with the triple window behind the apse is the sanctuary.

The cut-away looks through the ambulatory into the domed central core. The inside of the apse and sanctuary are not shown but we can see one of the concave exedra curving out from the core into the ambulatory. The sanctuary cuts right across it to the central core. The gallery just refers to the upper story of the ambulatory.

Moving inside, visitors enter into the ambulatory. There is a choice - either follow it around the perimeter or pass through one of the columned exedrae into the core. Today, the ambulatory has a heavy groin vaulted ceiling - the one that required the addition of the flying buttresses on the outside. This was added around 1100 instead of what was probably a flat timber roof. The vaulting is a better match for columned interior and central dome, but the walls weren't originally designed to bear the lateral thrust. Hence the buttressing.

View of the ambulatory with the vaulted roof. Note the textured stone paneling along the walls. This was a Roman custom for high status interior decoration that carried into early Christian times.

The groin vaults in the ambulatory from below. We don't believe that they were ever decorated.

The first part of the stepping into another spiritual world experience comes from the shape of San Vitale. Using bulging columned exedrae instead of walls or even straight colonnades creates the impression of a moving indeterminate space. A spatial experience different from anything in everyday life.

The way the exedrae push into the ambulatory give flowing glimpses of the core & makes the interior seem mysterious.

The vaults may not have been decorated but the carved capitals on the columns and ornamental tile floor are originals

Columns and capitals are a central part of Classical Greco-Roman architecture, but San Vitale's also show the transition into the early Middle Ages. The giveaway is the disappearance of the standard Classical orders for newer versions.

Close-up of a Byzantine-style basket capital. Entering the Middle Ages, Classical orders - Tuscan, Doric. Ionic, Corinthian, Composite - all fall out of use. The basket capital has foliate elements but is different.

Detail of the floor mosaic. Mosaic floors were a Roman tradition that carried over. The peacock retains it’s meaning as symbol of the Resurrection.

Seven sides of the central octagon are exedrae - the eighth is the sanctuary and apse. This cuts completely across the ambulatory, making it the terminus whether you go left or right from the entrance. Of course, the break isn't a sharp wall but triple arch with columns, giving a partial view into the decorated space beyond.

It looks like this...

The whole interior experience of San Vitale is moving, shifting views hinting at something wonderful across the veil. There difference here is that you can step through and see it.

An exedra bulges towards you. Pass between the basket capitals of the curving triple arch...

... and look up past the galleries on the opposite side towards the central dome. The apse and sanctuary are directly across.

The center of San Vitale is visionary.

The painting in the dome is from the 18th century. The Baroque angels are spectacular but a little out of place in the early Christian setting.

But the curving shapes of the exedrae with their galleries & windows create a flowing, mystical space.

Step out of this world.

Photos can't do it justice, but these are pretty good. Turning the octagon’s sides into concave exedrae with curving arcades makes the interior feel less solid & material. The massive exterior brickwork seems to melt away into a mindset more conducive to sacred encounter.

The structure is simpler than the visuals would suggest. It uses Roman vaulting techniques to raise the dome on a ring of self-supporting arches. The bulging exedrae with the galleries function like buttresses to counter some of the lateral thrust from the dome. Relieving arches - vaults built into the walls to transfer forces - in the corners above each pier and between and below the upper windows contain pressure in the transitional area between the upper circle and lower octagon.

Look at the picture right above and compare it to the diagram.

Red arrows show the downward force from the dome, around the relieving arches to the gallery vaults and on to the piers. Vaulting is like a skeletal system that makes large masonry spaces possible. The purple arrows show the buttressing counter-thrust of the gallery vaults pushing in. The green line marks the surprisingly stable base on the gallery vaults to hold the dome.

Looking from the ambulatory into the center catches some of how this space seems to ebb & flow around you as you move through it. Immaterial or less material describes it - especially when compared to the impression of a heavy polygonal exterior.

The light and decoration add to the otherworldly experience. The only place where the complexity resolves into clarity is upward. Everything flows into the circular dome. Structurally, it's a natural result of the vaulting. But symbolically it marks heaven as the ultimate answer that clarifies the world's mysteries.

The sanctuary & apse are the focal point of San Vitale and where the most spectacular mosaics can be found. These mosaics are what make the church such a treasure of early Christian art. The group is extensive and well preserved so we can still appreciate and understand the meaning. And how art worked to create a message in the early Christian era.

The sanctuary breaks through the two stories of the ambulatory & stands out from the rest of the flowing, immaterial space.

Look towards the sanctuary and the flowing space of the central exedrae. The sanctuary and apse are the bright greenish opening on the left - the sanctuary the bigger two-story space and the apse the smaller one that extends off the edge of the picture to the right.

The color comes from the mosaics and brightness from the additional windows. As the location of the altar and ritual focal point of the church it is supposed to clearly stand out.

And a look straight in. There's ornamental stone paneling on the lowest level and mosaic decoration above that up to the ceiling vaults.

Enter the sanctuary through a colorful arch with fifteen mosaic roundels or circular pictures. The triple arches on either side open into the ambulatory. The side walls are divided into two levels. The lower is between the ambulatory arches and the bottom of the upper triple arched opening connecting to the gallery. The upper surrounds the gallery opening. The mosaics show scenes from the Old Testament below and the New Testament above.

The far wall is mostly the arched opening into the apse with more mosaic above that.

The appeal of mosaic comes from the vivid colors and effect of light on the reflective surfaces. A mosaic is a picture made up of individual tiles called tesserae set into mortar like pixels. It's an old technique that goes back to ancient Rome and the Near East and is very durable. To destroy a mosaic you have to destroy the wall. The tiles are mainly glazed pottery, fired at high temperatures and made shiny by the metallic glassy finish, although pieces of colored glass and semi-precious stones could be used as well. Gold mosaic tiles use real gold foil hammered extremely thin - gold maintains it's color and reflectivity at extreme thinness. This is bright, visually splendid, and luxurious.

Take a look at the mosaic of Empress Theodora from an angle. The rough texture of the tesserae is easy to see. This - along with the reflectivity of the materials - creates the flickering shimmering effect. The placement of the tesserae is also representative. Look how her halo seems to radiate outward while the rest of the gold background doesn't.

The arch between the nave and sanctuary is called the triumphal arch. As in the triumph over death through salvation that was reenacted in the ritual of the Mass that took place at the altar. Early Christian art coordinated the positions and subjects of the pictures to turn the space into a symbolic experience that you walk into.

The roundels on the triumphal arch depict the twelve Apostles with the martyred sons of St. Vitalis at the bottom and Jesus in the middle. Each has a name.

Much of the fantastic effect of San Vitale comes from all the colorful abstract decoration. Shapes, plants, animals, stars, etc. - a feast of vibrant color

A close-up of St. Gerbasius - a martyred son of St. Vitalis - shows the mosaic technique. Gold was used to make the halo shine. The artists were very skilled, carefully selecting textures and shades to create subtle light and shade effects.

The costume is associated with the Roman elite. It may be consistent for the Vitalis' sons, but doesn't fit the historical reality of the Apostles. Meaningful associations for the audience re more important than strict accuracy. The average sixth-century person isn't going to be too up on first-century fashions in the Holy Land. They will recognize late Roman styles, so showing the saints as patricians also shows their importance and nobility in a language people will understand. Heavenly aristocrats gets the idea across.

The martyr is certainly worthy of that status. What greater commitment to faith over this world is there than laying down ones life for it?

The other side of the arch. Each saint is individualized but shown in a common format that shows their group identity. The Apostles and later martyrs belong to the same sacred "family".

Putting the saints in that order around the triumphal arch isn't random. The two Roman martyrs are placed lowest and closest to the visitor - just as they are in time and culturally. The Apostles are above them - higher physically like their status and historical proximity to Jesus. Then, at the top, the most important Apostles to the Romans - Peter and Paul - flanking a roundel of Jesus.

Note the golden background and rotated orientation. The saints support the savior who looks right at you as you enter. The cross-shaped or cruciform halo was a standard Byzantine, early Christian, and medieval indicator of Jesus. The rainbow represents God's saving promise and, along with the gold background, Jesus' cosmic nature.

The choice of costume is important too. Just as the saints are shown in patrician Roman garb, Jesus wears the purple robes of an emperor. Christianity started as a religion of humility - it is an oft-stressed Biblical virtue - but things changed once Constantine converted and it became the imperial religion. There was a tradition of treating the emperor as divine, ascending to heaven after death or conflated with the sun god or Sol Invictus. The monotheistic nature of Christianity prevented claims of divinity, but the imperial cult adapted and the emperor became a sort of Neoplatonic image of Jesus. Reciprocally, Jesus became portrayed as a heavenly emperor.

This mosaic in the apse of the Roman church of Santa Pudenziana dates to ~385-415, making it one of the oldest. Note how Jesus is already in golden robes and enthroned on a jeweled throne. The Imperial Christ as emperor of heaven was well-established by San Vitale a century and a half later.

Early Christian symbolism corresponds with location in the interior - in this case on the triumphal arch. Since the arch is the transition into the more sacred space of the sanctuary, entering it means passing intercessory figures of rising status. Martyr saints, then Apostles, then Jesus himself mark the crossing.

Look back from the sanctuary, through the triumphal arch, back into the domed nave. It's a nice contrast between the spaces and a look at the symbolic transition.

Entering the sanctuary confronts us with a wealth of mosaics. The side walls are divided into two levels - scenes of Old Testament sacrifices on the bottom and New Testament Evangelists up above. Hierarchical arrangements of the Testaments were common in early Christian art because they visualized typological connections. Early Christian theologians interpreted the Old Testament as prefiguring the New - not just through prophecy, but structure and symbolism as well. Old Testament characters, events, numbers, and other signs were taken as foreshadowing things in the Gospels. Putting an Old Testament scene under a New one shows how one rests on and fulfills the other.

The sanctuary with its two-level division. Note that the ceiling is vaulted and the arched structure marked out by mosaic patterns. Knowing that early Christian art coordinates subjects and placement for symbolic purposes, we can be sure that the structural configuration will correspond with the images chosen.

The lower level of the right side wall shows Old Testament sacrifices of Abel & Melchizedek surrounded by prophets Isaiah & Moses.

Above them, Matthew & Luke along with their symbols of man & lion flank the window.

The basket capitals in the sanctuary have another level of ornateness. The vines and flowers are carved out deeply and backed with color. Up above, an pair of lambs and a cross alludes to the Christological theme of the mosaics.

It's the mosaic work that really steals the show. Look how intricate they are, even when not depicting figures or scenes. these colorful abstract patterns are complemented by the grain in the marble columns and the basket capitals to make an overall spectacular display.

The meaning is carried by the pictorial mosaics. The main lower scene on this wall is the Sacrifice of Abel & Melchizedek. It ties a lot of ideas together into an imperial Byzantine flavored interpretation of Christianity. Melchizedek was a relatively minor figure in the Genesis narrative - especially compared to Abraham - who became an important symbol because he was priest and king. This made him a typological reference or prefiguration of am imperial concept of the Messiah. Since the emperor was conceived as a Nonplatonic image of Jesus, the combined political and sacerdotal authorities of Melchizedek became a foreshadowing allegory of the same dual nature of the emperor.

The nature of the sacrifices are significant. Abel's lamb makes a typoligical reference to Jesus, the sacrificial Lamb of God to come. Abel will himself be martyred as a result. Abraham offers a disk of bread that seems to glow. It's another sacrificial typology - this time to the Eucharistic wafer and made more obvious by the presence of the chalice on the altar. Rural and royal come together with symbolic references to Jesus' sacrificial body.

Historically, the emphasis on the Eucharist shows its replacement of the older custom of agape feast was well established by thus point. The relationships are almost diagrammatic.

Symmetry is used to show basic equivalence. The Old Testament altar is turned out like a Christian one. Lamb & Host, king & victim opposite the chalice beneath the Hand of God. The rainbow as always represents the divine.

The gemmated cross is symbol of Christ’s divinity. It, the hand of God & chalice make a vertical heaven-earth axis. Mirrored angels align with Abel & Melchizedek to further emphasize their equivalence.

There are two depictions of Moses to the left of Abel. One is a direct reference to Biblical narrative, the other is more symbolic. Although placed in the same late Classical landscape setting, they are not talking place in the same time and place. The "integrity" of the image is one place where early Christian and medieval pictorial story-telling is different from modern ideas of art. Ironically, it's the modern version that follows Aristotle's unities of time and narrative by showing one single moment in per picture. The older form didn't necessarily treat the background as a unified vision and could include multiple events or the same figure multiple times.

The upper figure is Moses surrounded by fire on a hillside representing of the Burning Bush.

The lower is more typological - Moses tending to sheep foreshadowing Jesus as Good Shepherd.

Like the Apostles in the triumphal arch, Moses wears Roman attire and not what you'd consider Bronze Age Middle Eastern garb. It's the same idea - the patrician costume and hairstyle indicated him as important and a leader in a way the San Vitale audience could understand.

Here's another look at the Burning Bush scene. The whole mountain is aflame - maybe suggesting the blazing light of God. Note the hand of God at the upper left directing Moses. It makes a connection with His presence in the Abel and Melchizedek scene, complete with rainbow clouds to indicate the divine. Removing his sandal because he's on sacred ground is a nice narrative touch.

The prophet Isaiah is on the other side of the wall next to Melchizedek. He is also dressed in Roman attire but isn't involved in any identifiable activity. He stands next to a crown to show his lofty status and carries a scroll to indicate his prophecy.

The art is technically good. Isaiah is in a classically-derived pose, standing naturally and turning to look over his shoulder. The sweeping lines of his robes nicely complement the shape of the panel and the background forms.

Technical close-up of Isaiah showing his features, wrinkled robes, and mottled gold halo. The different tones enhance the glittering effect of reflected light. Note the use of color and brightness to make his beard seem three-dimensional.

The sanctuary wall mosaics put the Evangelists over the Old Testament scenes and prophets, just as the New rests on the Old spiritually. Matthew & Mark appear above the Abel & Melchizedek scene. Each of them is beneath a symbolic creature - the four beasts of the tetramorph that came to represent the four Gospels and their writers in the early Christian period. There is some variation in the relationships, but the most common connects the man to Matthew, the lion to Mark, the ox to Luke, and the eagle to John.

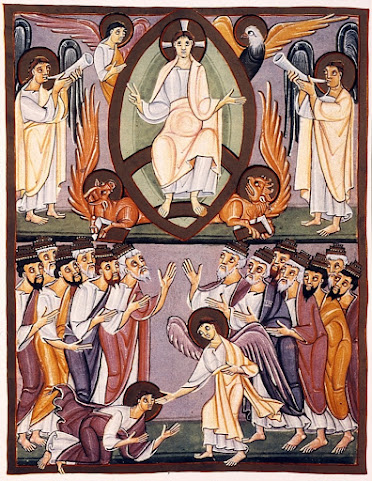

The Biblical foundation for the Tetramorph comes mainly from two places - the books of Ezekiel and Revelation. Here's Jesus enthroned surrounded by the four beasts of the Tetramorph from an illuminated manuscript from around the year 1000.

Jubilation over the fall of Babylon, circa 1000, Bamberg Apokalypse, Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, MS A. II. 42, folio 47 verso

And I looked, and, behold, a whirlwind came out of the north, a great cloud, and a fire infolding itself... Also out of the midst thereof came the likeness of four living creatures... As for the likeness of their faces, they four had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and they four had the face of an ox on the left side; they four also had the face of an eagle. Ezekiel 1:4-10

And before the throne there was a sea of glass like unto crystal: and in the midst of the throne, and round about the throne, were four beasts full of eyes before and behind. And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast like a calf, and the third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle.

Revelation 4:6-7

The appearance of the Tetramorph symbols in 6th-century San Vitale shows how well-established they were by this point.

Matthew & Mark sit in stylized classical like Moses and Isaiah landscapes writing their Gospels. The common setting shows the basic connection between the two while the relative position shows their different spiritual status. Mark’s Tetramorph symbol is a man - in a clever touch the man doubles as the angel bringing the divine inspiration of his Gospel.

The inclusion of symbolic birds - the stork & peacock - are allusions to the Resurrection that tie to the typological salvations below.

Close-ups of the Tetramorph symbols. The man/angel gestures towards Matthew’s head as he writes, touching his head to show inspiration. Mark’s lion is modeled in golds and browns and is very ferocious looking.

The opposite side of the San Vitale sanctuary repeats the same configuration of Old Testament scenes & prophet under two Evangelists - Luke and John to round out the four. The big idea is to surround the visitor in a sensually pleasing environment where the meaning of the pictures adds meaning to the experience of beauty. The glittering splendor also relays a message. Conversely, the beauty makes the message more appealing. This symbiosis can be described in terms of rhetorical and dialectical appeal. The beauty and splendor create an emotional response, the narratives depict a logical - literally typological - network of Biblical references, and the two reinforce each other.

On this side, scenes from the story of Abraham appears in the lunette with Jeremiah & Moses on either side.

Both sides separate the Old and New Testament levels with mirrored angels carrying a gemmated cross. The cross is a symbol of the divine nature of Christ - note the rainbow ring around it - that connects the two Testaments around the fundamental Christian mystery.

It is important to remember that San Vitale was completed after the Byzantine reconquest of Ravenna and that that had a religious aspect as well as a political one. The new Byzantine regieme was Orthodox unlike the Arian Ostrogoths, and had a different opinion on the nature of Jesus' divinity. Symbols like the gemmated cross make an Orthodox statement emphasizing Jesus' divine nature in a context where it had been denied.

Classically-inspired angels with the gemmated cross. Gemmated just means decorated to look as if it is covered in gems.

The angels increase the symmetry and match up with their counterparts on the opposite side.

The main Abraham panel combines two scenes. The left and center are taken up by the three visitors from Genesis 18 with Abraham and Sarah bringing their meal. On the right is the sacrifice of Isaac.

The story of the three visitors is interpreted as an Orthodox allegory of the Trinity and a rebuttal of Arian ideas. And the Lord appeared unto him in the plains of Mamre: and he sat in the tent door in the heat of the day (Genesis 18:1). Jesus can't be part of the Trinity - a hypostasis of God - if he lacks a divine nature. But there's more to the symbolism - a complex but specific typological reference to Jesus.

On the left is Sarah, who will have a divinely-inspired birth. And he said, I will certainly return unto thee according to the time of life; and, lo, Sarah thy wife shall have a son. And Sarah heard it in the tent door, which was behind him (Genesis 18:10). The congruity with the birth of Christ is exactly the sort of thing typological prefiguration drew on.

The little structure that clearly is too small to be realistic is a carry-over from Roman art, where minimal architecture was used to suggest setting. This carries through the Middle Ages.

In the center group, the representation of God/Trinity appears with bread that resembles Eucharistic wafers. Together they form an allegory of God - or one hypostasis or the Logos - incarnating and dying for us. The link is reinforced by the circular shape of the bread-hosts & Trinity halos.

This is the same Eucharist that the real communicants at the real altar right below took part in. You see the divine meaning in your communion.

In the right, the theme of sacrifice makes another connection to Abel and Melchizedek on the opposite wall. Note the familiar hand of God with rainbow clouds in the usual role of showing direct divine intervention.

The typological symbolism of early Christian art can be quite inventive. Look at the two lunettes together in relation to the real Mass on the alter between them and the Orthodox rejection of Arianism. The Incarnation and redemptive sacrifice of Jesus, contemporary ritual reenactment, and theological debate can be foreshadowed visually by carefully placed and related depictions of Old Testament stories.

Jeremiah & Moses are the prophets above the Abraham scene. They further support the typological connection to the salvation of humanity through Jesus. Matthew - the most genealogical Gospel - provides the link between Jesus & Jeremiah. Moses is receiving the Old Covenant that foreshadows and is replaced in the new.

Close-up of Jeremiah with his prophetic scroll. Probably the one ignored and burned by Jehoiakim , but it could also be a more generic reference to prophecy. The crown - like Isaiah's opposite - alludes to the ultimate triumph that he predicts. Note the enduring Roman attire. The costumes are excellent.

Moses appears on a fantastical mountain setting & looks down towards the viewer in the sanctuary below. The hand of God is shown handing him the Commandments in scroll form.

The position of the Apostles is the same as on the other side - John & Luke in Roman garb seated in a post-Classical landscape beneath doves, urns & vine scrolls. Here too, the symbolic beasts of the Tetramorph appear above them - John's is the eagle and Luke's is the ox or bull.

John is on the left with his writing table with pen & ink, Gospel, and symbolic beast. The eagle was associated with John because his Gospel is the most celestial in it’s metaphysical discussion of Logos.

Luke sits with his Gospel & basket of scrolls. His ox or bull association may come from the prominence of the Temple and its sacrifices in his Gospel. Luke’s is the one that tells of Jesus’ presentation & debate with doctors in the Temple.

The mosaics continue into the vault of S. Vitale in Ravenna is a vision of mosaic color & symbolic decoration. The Lamb of God at the center lines up with the bearded Jesus seen earlier in the rainbow at the center of the triumphal arch. Four angels surround the Lamb, one in each highly decorated quadrant. The quadrants alternate primarily green and gold hues and are separated by ornate bands. We can’t think of another ceiling quite like this.

The decorative plan features Roman-derived vine scrolls & plant motifs only cranked up to a higher pitch by with shining mosaic color. Roman art used vegetal and abstract forms to create ornate backgrounds, and this crossed into early Christianity. The difference is that the Roman versions tend to be clearly delineated even when intricate. Early Christian art is trying to create an overall experience of heavenly splendor that feels like another world. Remember the contrast with the plain undecorated exterior. At San Vitale, it's the vivid colors and shining mosaic surfaces that add this effect.

Each quadrant had an angel on a globe supporting the central roundel with the Lamb. The detail is almost lost in the shimmer on the tiles.

Lively animals fill the spaces, but balanced spacing prevents the impression of crowding.

Close-up of an angel in Roman robes standing in a version of the classical contrapposto. The bland, wide-eyed expression is typical of early Christian and Byzantine art. The globe it stands on represents the world, indicating that this is a metaphysical representation. The animals emerging from the decoration probably symbolize life and fecundity under the rule of the Lamb/Kingdom of God.

The colors are eye-catching, but note the 3D effect created by subtly blurring the edges of the forms & strategic use of white tiles.

Another good look at the detail. Life and fecundity certainly fit the decorative bands that mark the structure of the vault. The peacock was an early Christian symbol of resurrection and immortality.

Meaning corresponds to placement. The vaulting physically support and lead to the Lamb of God in the center so the decoration represents the life and salvation that the Lamb is the source of.

The Lamb of God in the center. The bright white tiles against the shadow on his forehead makes his head appear to shine in the dim light of the sanctuary. Almost like it is bedecked in stars.

The ring around the Lamb is filled with vegetation and fruits. More life.

The last group of mosaics in San Vitale are in the apse - a cosmic enthroned Jesus over panels of the emperor & empress on the side walls. The placement-subject correlation still applies but it's different. The vertical arrangement is still symbolic but not expressive of Old and New Testament typologies. Now the relationship is a metaphysical one relating earthly to heavenly power structures. It's as purely false as any other secular transcendence, but that's typical of the imperial jacking and inversion of Christianity.

Unlike the satano-globalist beast system, the lie is surrounded by Christian truths to provide a moralizing veneer. The beast system rejects this because it implies that Christianity is a moral standard. One adds a false dimention to an objective moral frame, the other rejects and inverts the frame itself. Different points on the same continuum of secular transcendent decline, but still different in the moment.

Jesus in imperial purple enthroned on the world is the Neoplatonic image of cosmic emperor. The Byzantine emperor and empress Justinian & Theodora are shown below as his earthly manifestation.

The vertical relations & similar arrangements in the pictures diagram this imperial theology.

The curve of the apse semi-dome helps it stand in as the vault of the heavens. The shape also makes it into an environment. Apse mosaics wrap around the space below, bending & drawing you into a more physically real relationship.

This photo shows how the curve of the apse makes it seem like Jesus and his entourage are bending down towards you. It doesn't show in head-on shots because the photos flatten the curve.

The apse mosaic features a beardless Jesus enthroned on a celestial globe wearing imperial purple & gold. This is the same emperor archetype seen in the roundel at the beginning of the post, but with a more youthful appearance. St. Vitalis, Bishop Ecclesius who started the construction & two angels are arranged around him like an imperial court.

The figures are set in a paradisiacal garden that is not of this world. The rainbow presence of Jesus' throne - a representation of either the world or the cosmic spheres - shows the figures are in a different place metaphysically. It is a depiction of heaven imagined as an imperial court, with Jesus as model emperor and the saints and angels as his courtiers.

The young beardless Jesus was common in early Christian art. This is a fairly late example - the bearded version in the roundel is closer to the standard look familiar to us. The cruciform halo indicates his identity without doubt.

Here he extends the martyr’s crown to St. Vitalis & holds a scroll symbolizing the word of God. The shades of blue in the sphere - reference to the world and/or the interlocking spheres of ancient cosmology are especially striking.

Close-up of Jesus’ face with his identifying cruciform halo. This was limited to Jesus. The mottled gold tesserae enhance the sparkle.

Wide staring eyes in late imperial portraits as a symbol of power and authority.

Jesus’ heavenly court gathers beneath rainbow clouds and a solid gold background. The rainbow is a sign of the divine and the gold has a couple of effects. The shining background shows that this is a mystical space of golden light and not anywhere in the material world. Without a sense of place, the figures seem to float before this radiance, suspended between divine abstraction and our reality. Combined with the forward lean, they really seem intercede between us an heaven as they do theologically. The way they are placed reinforces the meaning and effect.

On our left. St. Vitalis receives his crown of martyrdom.

Note his incredibly elaborate robe. Luxury here becomes a symbol of his spiritual status, marking his as a sort of "spiritual aristocracy".

On our right is Bishop Ecclesius who began the construction of S. Vitale, although it was Bishop Maximian that finished it.

He presents a small model of his centrally-planned church - this type of offeringwas a common way patrons of major works were shown in early Christian & Byzantine art.

A few other features of the apse wall add to the symbolic content. Above the apse are depictions of Jerusalem & Bethlehem the central cities in the Gospel story and settings for the Incarnation and Passion of Christ.

The cities are labeled - otherwise they're not recognizable. The use of small, symbolic references to places was common in early Christian art and continued through the Midle Ages.

At the center of the apse arch is a gemmated chi-rho in a divine rainbow ring. these are the Greek initials of Christ and a common symbol for him.

Among other things, S. Vitale is a treasury of early Christian symbolism.

Above the chi-rho, a pair of mirrored angels tie the wall to similar pairs on the side walls. These wear the same type of Roman garb but carry a colorful starburst pattern that picks up on the design of the initials below. Effective unity across types of imagery and areas of the interior.

This has been a long journey. The final mosaics show the Emperor and Empress and their courts as worldly expressions of Jesus's divine imperium. It’s an assertion by analogy with Justinian as Neoplatonic image on of God on earth. We already noted how the cult of the emperor was transposed onto Christianity. This is a more direct assertion of the relationship.

The Justinian fresco curves slightly with the wall. In this view, the heavenly garden in the apse mosaic under S. Vitalis is just visible around the window arch.

Note the stunning marble inlay below.

Close-up of the marble inlay in the apse. The Romans traditionally used colored stone panels on the walls of luxury buildings. This is a late but stunning example of that art. More intarsia than mosaic, the patterns complement the rest of the interior.

Justinian appears at the center of his entourage, just as Jesus does above. The group includes Bishop Maximian who finished the church and is identified by name - remember the late Bishop Ecclesius is already shown in heaven. The inclusion of secular & ecclesiastic figures around him show his dominance over both spiritual and worldly affairs. Note the imperial purple robe that associates him visually with Jesus. The red shoes are... interesting.

Imperial Christianity hijacks & inverts scripture & tradition from the early. The idea of emperor is a metaphysical icon of Christ is pure secular transcendence and an inversion of the Biblical charge to render unto Caesar what is Caesar's and God what is God's. The conflation of worldly and sacred authority is a forerunner of the Christian humanist blasphemies of the Renaissance.

The mosaic is stunning though.

On the left are the secular powers - the generals & soldiers, possibly including Belisarius who reconquered Italy. Their presence would be powerful given the recent conclusion of the Gothic-Byzantine wars.

Note the chi-rho shield carried by the soldiers. Christian warriors with the same initial seen in gemmated in the sky above.

On the right - bishops & deacons including Maximian with gemmated book, cross, and incense censer. Bald Maximian looks like a portrait. He became bishop near project’s end & may be a last-minute replacement for his late predecessor. Hence the label.

Secular & sacred authority. Together with the soldiers, they embody Justianian's authority across the sacred and secular domains.

Justinian occupies the center in imperial purple mantle & gold tablion with woven birds. The detail in his garments and crown is phenomenal. Like Jesus he occupies the center of his court

The basket he carries is likely for offerings.

Technique close-up of Justinian’s face. Different color tesserae model his complexion. His jeweled crown is very detailed. Note the halo with hints of cosmic rainbow to assert divine status and connect him to the scene of Christ above.

Mortal vanity has always plagued the church.

The last of our S. Vitale in Ravenna mosaics is the Empress Theodora & her entourage opposite Justinian. It’s designed as a companion piece with similar lay-out reflecting their different realities in the Byzantine court. Theodora is in imperial purple with a halo & holding an offering like her husband. The curve of the apse makes it seem as if the curtained door actually leads out of the scene.

Imperial status as worldly image of Jesus. Her advisors & ladies-in-waiting are hierarchically arranged around her. The details & colors are stunning. Like the architecture feature that covers Theodora like a canopy and fits the curve of her halo.

Empress Theodora & her entourage shows the lavish detail of San Vitale mosaics. The flatness & staring eyes show that eastern-flavored transition from classical to medieval art. But the details like the fountain & curtain are engaging.

Close-up of Theodora. Staring eyes & blank expression go back to late imperial authority portraits. The detailed crown, natural folds of her falling robe & modeled complexion are just remarkable.

The hint of rainbow in the halo shows her divine status like that of Justinian and ties her to Jesus above. Her robe shows the three Magi - high- status figures with obvious royal appeal to an imperial Christian.

Technique close-up. The pixelated picture-making is astonishing, especially to eyes accustomed to shoddy modern garbage.

Put the three together & the visual relationship is clear. The imperial couple manifest Jesus’ heavenly imperium on earth. The rainbow halos of the emperor & empress indicates this divine conduit through their exalted personages.

Too bad it was inverted nonsense.

Secular transcendence fails because material reality is time bound and changing. Metaphysical absolutes can't exist here. They can be represented, but they can't be found in and of themselves. This is a central observation that runs through the Band and the basic reason why every attempt at forging a utopian ideology of human perfection fails. An when flawed fallen humans pretend to be pure arbiters of divine Truth? The history speaks for itself.

The mosaic artists of San Vitale are brilliant. Absolute masters of their craft. Theodora seems to pulse with radiant divine light. But it's still just a picture, and what it depicts is subject to reality.

Shortly after San Vitale, the Byzantine Empire began centuries of long, slow decline. Forget image of Christ - there hasn't been a Byzantine emperor for almost 600 years. Half-assed Ottoman blathering about Third Rome doesn't count. The depiction is false.

But the beauty isn't.

San Vitale was produced in a climate where Logos was the arbiter of Truth. Where even the vain auto-idolatry of emperors took place within a frame of objective morality. And where God was the highest good. This was an environment where the good, the beautiful, and the true express the same underlying nature of reality. Perhaps not visible in itself, but representable in works of breathtaking sublimity.

People often look at the garbage culture vomited out of the beast and wonder what happened? Why can't we have spaces like San Vitale? Not necessarily the style - there are plenty of beautiful structures from other periods - but the quality? The answer is that we could. We just need to reconnect as a culture with the essential element that made expressions like this possible...

No comments:

Post a Comment