A review & reflection on Dantes recent & all time.

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check regularly and it will be up there.

Joseph Noel Paton, Dante's Dream, Bury Art Museum, 19th century

Why do we care about Dante? That would have been obvious at one time, but now? It should be...

Time for another positive post - this one really different again from the others. Instead of 20th century fantasy novels or movies we'll look at an all-time literary giant. There are some reasons for this - not that we need any for Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) or his Divine Comedy (1308-1320) - one of the greatest artistic achievements by anyone ever. But as Western institutions betray their cultural stewardship, Western people have to pick up the slack. And this means reacquainting generations with the culture that their indolent elders abandoned.

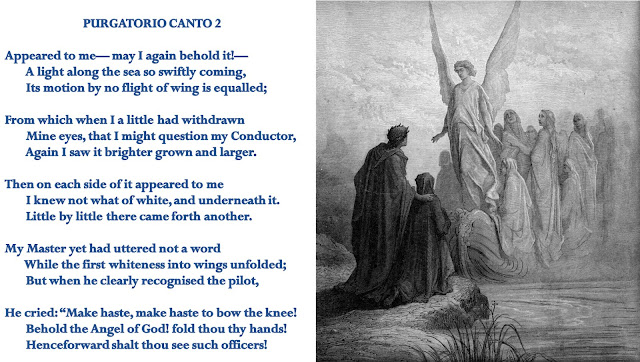

Turns out Dante had an image for that - translation by Longfellow.

In a morally polarized universe, refusal to choose is an all-around loss. As useless in the afterlife as they were in life. This is something easy to see in the world around us. The wisdom - the logos - in Dante is that he makes it so vividly and memorably clear after so many years.

But Dante has always been a writer for every season - why him now? The immediate reason is the recent appearance of Dante in a couple of different forms around Band HQ. Since cultural heritage, beauty, and logos are big parts of what we do here, it all just fit.

The first is part of a much larger project by Castalia House, a boutique Europe-based publisher. Their leather-bound premium issue of the Henry Longfellow translation of the Divine Comedy is one in a new ongoing series of collector-quality books.

It's a subscription service but single copies are sometimes available. Limited print run so they do sell out. Here's the link - more on them later.

The second is somewhere between a translation and retelling by a celebrated Scottish writer. "Englished" is Gray's invented term for this type of reiteration. Here's a link.

The two are as different as the covers suggest. But both have something to say about this bigger problem of cultural rejuvenation. It was thinking about the two perspectives together that gave us the idea of a review. Not just a summary and an opinion - an old-time review with commentary and reflection too. We'd done something similar with Vox Day's Jordanetics - a book we still consider an essential read for anyone inclined to spare a moment's thought to that luciferian fraud. But looking back, those posts tilted too far into the commentary and didn't say enough about the book.

A good review strikes a balance between expanding on the subject and breaking down why or why not to read or watch it. The other Truth of Culture posts art do that - but they are looking for logos structures in a cultural brownfield. They aren't reflecting on the whys and hows of canon formation in cultures. Maybe the Silmarillion posts to an extent - but even they were more into the epistemological failure of modern academe than really considering why great literature is great.

Figuring out how to talk intelligently about cultural things is a huge part of the culture of the West. There's an English tradition of expansive reviews - from Dr. Johnson in the 1700s to the dim revenant that is the New York Review of Books - that have always had a self-fluffing air. The feeble narrative service has become more transparently pathetic, but look around - what is Johnson's contribution to modern England?

Better question - who will bother retaining Johnson's prolific tripe when organic culture rebuilds from the detritus? The whole notion of "man of letters" is a masturbatory joke unless they connect to wisdom by pointing towards Truth. Otherwise it's just wordy justification for self-pleasure and moral entropy.

Seriously. Here's a flack telling us Johnson was "first great modernist" and "the greatest subject in the English language of the first true modern biography, produced by his protégé Bozzy..." On what grounds? One might think the point of the article - the anniversary of the obesity's passing going unnoticed - is sufficient proof to the contrary.

Not that Johnson couldn't write. But without substance that's just entertainment. Diverting word strings. The opposite of lasting value. Or what the modern beast system pretended could replace "values" as foundations of culture. Note the incestuousness of Johnson's "Club", which included head of the Royal Art Academy Joshua Reynolds, epically overrated intellectual flyweight and secular transcendence mouthpiece Burke, and Bozzy.

John Sartain after James William Edmund Doyle, A Literary Party At Sir Joshua Reynolds', 1851 engraving.

From left: James Boswell Samuel Johnson Sir Joshua Reynolds David Garrick Edmund Burke Pasquale Di Paoli Charles Burney Francis Barber (Possibly) Thomas Warton And Oliver Goldsmith

So why do we care about Johnson? Because the self-idolators declared "culturally important" are the same ones making up the lists. Where talking bags of suet belch inversions like "patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel" and dimmer traitors and mindless materialist automatons nod along blankly. Where secular transcendentalists praise each other for vacuous nonsense like their 'timeless insights into the human condition'. Timeless - apart from always less logos and more secular transcendence.

They were wrong. Bury them.

David Levine, Caricature of Samuel Johnson

Really, is there any better icon of cultural impoverishment and bobble-headed mummery than the "wit" of a David Levine "literary caricature"?

The 20th-century beast system perfected the art of making affluent vacuity appear sophisticated. At least until the cumulative weight of abandoning credible ontology or epistemology finally stilled the momentum of historical high-trust, high-performance, intrinsically moral societies.

The crazy thing is that even with all that historical beast-dancing and narrative-huffing, there actually is value in reviews and criticism that points to truth. Like so much inverted modern culture, the idea is sound. The form isn't even bad. The Band has fallen into this a little with the more positive posts. A review that walks through what makes something worth your time and how it ties into larger truths.

Of course, the beast has better production value than we do. And copy editing. They've also got us beat on secular transcendent narcissisms, pomposity, and ontological poverty. On the flip side, we're a little bit smarter than the narrative-huffing shills... and we serve Logos...

Your call.

So why read Dante?

Start with an anecdote. A not-so-funny thing happened on the way to mass higher education – the “Great Books” list. The Band has already pummeled this sad proxy for systemic decline in an earlier post – no need to waste the bandwidth here. Here's the historical pattern.

Library of St. Gallen, a library in a monastery founded in 719, with over 400 codices from before 1000. Canons of literature form over the Middle Ages and into the Modern era. This is organic at first – favorite stories and most respected writers. A mix of techne and appeal.

Before printing, people could read far fewer books. A few shelves of manuscript codices was an impressive library. We wonder how many nobles were as literate as they were because they worked through whatever was in the family collection out of boredom. Or listened while someone else read aloud. Since hand-copying rules out the fluff, they'd be exposed to the canon by default. A bibliophile would have to acquire a new manuscript just for something new to read. Scholars journeyed long distances to read basic canonical books and learned to commit contents to memory.

When the first Western canons are forming, there is a vastly narrower range of printed material. And vastly fewer people reading and thinking about it. The medieval Bible was a Latin primer but not able to fill the vernacular role it did in Colonial America. Devotional literature like the Golden Legend was really popular, and there was a selection of stories and histories. Personal libraries outside the elites were impossible. Most people didn't own a single manuscript. So the better-read all knew the same things.

Paul-Emile Froment-Meurisse, cover for the Breviary of Jeanne d’Evreux, a 14th-century illuminated parchment manuscript, 1895, engraved red gold, silver angels designed by Luc-Olivier Merson, enamel shield with arms of France and Evreux, clasp shield with arms of Navarre, chateau de Chantilly.

Once vernacular literature kicks in during the late Middle Ages, national traditions develop. Dante was a tip of the spear. His Comedy – named because of the happy ending, not because its funny – was written in Italian, not Latin. Vernacular literature existed but wasn’t taken seriously – troubadour songs, court diversions, folktales, etc. Dante changes that by writing in the loftiest style on the most profound subjects.

Domenico di Michelino, Dante and His Poem, 1465, fresco Florence Cathedral

The Comedy is a trilogy – one book each for Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory. The Domenico di Michelino fresco shows Dante in front of representations of each. Ironically, the image of Paradise is Florence - the native city Dante was exiled from for political reasons.

Unknown Master, Florence, Allegorical Portrait of Dante, late 1530s, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art

Purgatory only became a necessary addendum to the Bible around 1000 years after the Resurrection. Dante sidesteps this by presenting it as always having been there.

Discovered rather than invented.

We are uninterested in the theology – barring revelation, the sort of mechanism Dante describes is unknowable. The thing is, is poem does claim revelatory status of a type. It’s all set up as a dream vision that we accept as truthful. His guides are the revered Virgil and beloved Beatrice – trusted voices. And his vision doesn’t reveal things beyond him like the “face” of God.

The historical reality is that Dante himself played a big role in defining the idea of Purgatory in the Western imagination. It’s why he is in the Theology and the Poetry in the papal library we saw in the last art post [click for link].

Giotto, Paradise fresco, around 1336, Museo del Bargello, Florence

The oldest picture of Dante was painted a few years after his death by the Florentine master Giotto.

This is closer to what he really looked like - the red garb appears to be real, the weird witch's face, not so much.

Dante and Giotto (1267-1337) knew each other - the painter was two years younger though he lived a decade and a half longer. The poet had mentioned Giotto in the Comedy as an example of the fleeting nature of fame.

In painting Cimabue thought that he

Should hold the field, now Giotto has the cry,

So that the other’s fame is growing dim.

Purgatorio XI 94-96

This painting is an entertaining look at the two of them. Having read the Comedy, it's funny to picture the melodramatic Dante recounting tales to his artist friend.

G. Fettori, Dante and Giotto, 19th century, oil on canvas

Not themost spectacular picture but a nice humanization of some canonical figures.

The Comedy rings true like a personal testimony and clicks together on a cosmic scale like the Ptolemaic system. It’s peppered with historical events that add verisimilitude and cosmological insights that feel prophetic Individual personalities come through even with the poetic structure.

George Frederic Watts, Paolo and Francesca, 1872-1875, oil on canvas, Watts Gallery

Dante's image of the doomed adulterers' love as so strong that they find each other and spend eternity together in Hell is far more powerful than the original cliched tale.

And the medieval vision of an interlocking cosmos powered by divine love is as clearly presented as it will ever be.

Michelangelo, Caetani, Overview of the Divine Comedy, 1855

Dante's cosmos. The world is arranged on a line from Jerusalem through the center where Satan is to the mountain of Purgatory on the other side. Medievals saw physical geography and geometry as having meaning.

The Earthly Paradise at the top of Purgatory is the jump point to the concentric Aristotelian spheres. Each corresponding to a heaven, not a pagan god. True Heaven - the Empyrean Rose - is at the top.

It's not just the zipping between personal and cosmic. The Comedy is also rooted in recent and Classical traditions. The role of Virgil as companion and guide for the first two books is brilliant. Dante is a bit of a simp, and the Roman keeps things going when Dante's fainted. But he also makes a comparison.

It would have been assumed an epic of Dante's ambition would be written in Latin. Like Virgil's Aeneid. But Dante's Latin was wasn't his mother tongue - to rival Virgil as poet, he couldn't hamstring himself. He needed to write in Italian. And in doing so, elevated vernacular to serious literature. Because he does match Virgil in reality before surpassing him in the next world.

Gustave Doré, Dante is accepted as an equal by the great Greek and Roman poets, Inferno plate XII, Canto IV, 1861

Doré Inferno engravings were published in 1861 with Purgatorio and Paradiso coming together in 1868. Click for a link to the set. They are some of his finest works and maybe the best set of Dante illustrations.

This gets the idea of Dante as a poetic equal to the greats of antiquity. No back seat in skill. It's why he's in the Parnassus fresco. The message:

Vernacular poetry is as lofty as Latin

Gustave Doré, Beatrice, Purgatorio Canto 30, 32-33, designed around 1857, engraving

The arrival of Beatrice at the end of the Purgatorio comes with the disappearance of Virgil. The pagan - for all his talent - can't ascend beyond the earth. Dante gives the virtuous pagans Limbo - a place where they don't suffer, but have no access to God's grace.

Christian wisdom surpasses pagan in any tongue

The Divine Comedy shows what the Renaissance will invert - all the pagan skill and techne in the world is irrelevant without Logos. It also show something the Band will hammer on about centuries later - ontological relations can be conceptualized vertically. Consider the relationship between Dante's cosmos and our ontologically as basic patterns. He follows Aquinas and Aristotle by connecting the visible sky with metaphysical distinctions while we are less concrete. But the idea of progress from a Fallen material world through purified logical abstraction to an imperceptible ultimate reality...

See for yourself. Here's a link to the ontological hierarchy for newer readers.

The reason the poem rings so profound despite being so medieval is familiar to readers. Applicability. Dante sets it up as an allegory - not Tolkien's applicability - that follows the structure of what it represents very closely. He frames it as a dream - the allegory is that his epic journey corresponds to reality on different levels. There's the cosmology with the ontological-physical relationship between the material and the metaphysical. And there's the personal - with Dante's own inner progression mapping onto the outer epic one.

We don't see the world as a ball with a giant mountain breaking the atmosphere opposite the Middle East. So the cosmic beat-for-beat allegory doesn't hold up the same way. The dream narrative becomes more applicable - True on a fundamental level, but presented in a truly imaginative form. And the necessity of Logos to personal salvation is the same as it ever was.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Dante (He Hath Seen Hell), 1864, oil on panel, private

It appears that the simping was taken care of...

That's why we read Dante. A historical game-changer of indescribable scope that literally changed the literature of the West. Some of the finest Italian verse ever penned - similar to Shakespeare in English as a very old writer that is never surpassed in some ways. An unforgettable image of the interlocking nature of life, cosmos, soul, and God that is applicable in any world view. Great book sells it short - an epochal book by any measure.

So what's the problem? Why is this even a question?

For that, we have to follow another place where the noblest intentions of secular transcendence and Enlightenment idealism smashed into fallen finite reality.

To be fair, canons of literature are both natural and valuable signs of culture. But they actually have to reflect a culture. The 20th-century "Great Books" mini-fetish isn't that. Consider the granddaddy - the 54-volume Britannica Great Books and it's 60-volume sequel. Click for lists of titles and background info. Read the list. What culture is this expressing?

The "Great Books" fetish was a typical inversion. Take the idea of an organic canon of literature and pretend it could project the "timeless truths of the Western tradition". Where Modernism coexists with Dante. The "culture" it expresses is the degradation of actual organic culture into soulless materialist Flatland.

The "Great Books" inversion was typical of secular transcendence - something we call the Philosophical Bait and Switch. [Click for a link on secular transcendence - it's one of the Band's most important insights]. This is when something dependent and temporal is passed off as eternal to logos-less dupes who'll huff anything that lets them claim access to absolute Truth. The idea that a canon of literature is primal knowledge - written deeper than a spear is long - and not a product of the author.

This is obviously nonsense without metaphysics - something Flatland can't admit. So we get totems of modernist degradation and occultism like Freud alongside Shakespeare and Dante. One can only be relevant if we are tracing histories of secular transcendence and modernist decline. Which is what the "Great Books" fetish invariably does.

Because it gains Credibility! from a parallel inversion in the sociological heart of academe...

That's right. Complex learned culture that grew over centuries could be packaged and spoon-fed to disinterested masses as a “Liberal Arts Education” because reasons. Oh, there were rationales – there always are. Just nothing that would signify as "reason" to anyone not neck-deep in fake self-idolatry already.

Consider just how much textual and philosophical immersion required to be a true scholar in any historical sense of the word. It's cognitively impossible for this to be broadly available because there's a high IQ floor to do it. And it's not even a good use of high-IQ human capital past a point. Advanced society needs smart people for a lot more than cultural stewardship and speculative thought. So how could it ever seem a good idea to have huge swaths of the people wasting years of their lives on watered-down outlines of scholarship? That they have neither the interest or intelligence to make into… anything? Not a rhetorical question, because Dante wouldn't have seen the point.

Mass Liberal Arts Education (MLAE) was a slice of 20th century magical thinking filtered through institutional greed. The first part is that offshoot of post-Enlightenment secular transcendence - the larger satanic inversion is that we put wishes over reality for personal aggrandizement. Here, it’s the pretense that if we change the words and symbols we made up to describe something, the thing changes. Like pins in a voodoo doll.

The second is the need to "justify the relevance" of the humanities as bloated institutions oriented more towards printing job chits.

So the reality and the hollowed inversion can't be the same. They're inverses. Over time, learned disciplined thinkers and talented creators built up canons of national literature. The superheavyweights were translated and made a pantheon-tier trans-national canon of great literature. Status in both was based on quality and influence and mastery took a lifetime. There was no pretense that every shopkeeper and craftsman have once squeezed a de-moralized survey of classical literature and world religions in between rush and senior weeks.

But this level of learning can’t work for MLAE. It’s way too difficult and demanding. But you can turn some of the names into a formula, simplify it to the point of transformation, and peddle it to the masses as The Same Thing!

The problem is that the masses don’t care about the Liberal Arts - as

defined by 20th century university presidents or otherwise.

A wider view of Dante's crowd on Mount Parnassus. Apollo's poetic inspiration echoes in the Muses. And their grace is perfected in the poet Sappho's leaning pose on the window frame.

The visual beauty is a way of depicting the beauties of all the arts.

Now consider how the level of interest the average person you know has in any of this. And now imagine believing that mastering it should be some sort of public moral imperative - to the point where you restructure society. It's retarded.

Go back to the painting - unlike today, top artists were chart-toppers and critical darlings. Which meant something for everyone. You don't have to be learned or interested to note a pretty picture in passing. Or nod and think "hmm, ok. So that's what poetry is going for" before getting on. The rest wasn't developed for mass appeal or consumption. What mattered is that the creators and elites maintained deep logos-based culture that kept the popular appeal on a moral track. Evacuating the depth and expecting the husk to exert talismanic pull over the masses is the opposite.

The masses never did care about the Liberal Arts. They were something scholars pimped to nobles. The "elitist" description is a historical feature - they were by definition elite culture.

If there was mass appeal - meaning a critical mass of the population sees personal benefit - the Liberal Arts wouldn't be endlessly arguing against their irrelevance..

We know the rest.

Forget timeless - MLAE didn’t make it into the 3rd millennium.

Put aside the content and just think about what's happened. What definition of "Liberal Arts" can cover everything that's been proposed in its name? Not a rhetorical question - because the modern commitment to clinging to the term comes from its long history and all the associations of that.

The "Great Books" look to be about as viable. But great books don't have to be if you consider who makes the lists...

Look closely at the inversion. MLAE took the name of something that referred to hard work, discipline, and high innate ability that restricted its applicability. Watered-down versions were peddled to the elites starting in the Renaissance by self-interested teachers. Then the Enlightenment-era European aristocrats turned Renaissance culture into elite finishing school.

Pompeo Batoni, Portrait of Simpkin Poncington Francis Basset, 1st Baron de Dunstanville and Basset, 1778, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado

The vast majority of Grand Tour elites got nothing more out of their classical educations than a sense of style that excluded their countrymen. But it didn't matter because their prospects weren't dependent on fake intellectual meritocracy. At best, the goal was overall betterment, with the reality being a process of class definition.

It's not that the wisdom of the Western Tradition isn't there - it's that the general educational value of the Liberal Arts is limited by it's cognitive demands and impracticality..

The Liberal Arts come into the modern era with two faces.

1. High-end cultural activity and stewardship. By necessity a small group, but when healthy trickle logos into wider culture.

2. Watered-down aristocratic class marker. Superficial Classical education that gave social elites common frames of reference.

This is what carries into America, only filtered through the American version of aristocracy we covered in earlier posts. Elite schooling combined Grand Tour ethos with British-type institutions, but with hypocritical lip-service to diametrically-opposite "enlightenment values". So martinets pedestalize the demonization of their own society because the proper nouns remind them of Florence or Athens.

Because it didn't matter to them.

The Princeton Charter Club, Princeton, N.J., 1915

It was elite socialization - the content was irrelevant beyond giving them a common identity that made them feel superior to the masses. Gentleman's Cs and so forth.

However the "scholars" did care about the content. Enter Enlightenment inversion. One of its most monstrous anti-human elements is human fungibility. That we're automatons that can be swapped and plugged in and out of any context, motivation or aptitude. It's so self-evidently false that accepting it means nothing downstream functions in reality.

But the beast system runs on it - the appeal to misguided "fairness" mixed with arrogance and envy makes it potent. Words have been stretched into meaninglessness without acknowledging change until the system is teetering on the edge of collapse. MLAE is an example of this.

Whatever this is, it had no substantial connection to the Western Liberal Arts beyond the use of words. Mass involvement = mass intelligence, information levels, deep cultural interests, and attention spans.

The titles of high-end culture stewardship had already been falsely applied to a class distinction rite of passage. The timeless values and general betterment were already impossible lies used to justify fat tuitions and endowments to clients who were already elite. A sop, to feel good about pissing away your most vital years on busywork and play. The thing is, it wasn't really pissed away because - for the elites - the content didn't matter. The socialization was the point.

But suddenly the beast attacks the "elite" culture part of it while demanding that the fake the "universal good" be applied to all. For no reason other than "people who proved dead wrong said so". The real reason was envy - if we eat their hearts move our eyes across the same proper nouns, we become them! But real intellectual engagement on the cultural level is beyond the masses. And elite finishing only useful when your education doesn't have to be productive. Guess what happened?

MLAE applied an old title to something completely new and different on an unprecedented scale. And the masses danced along because they had no idea what actual scholarship or the Liberal Arts were. Because it wasn't something that was ever mass applicable!

Instead they trusted the "experts", handed over the keys to their culture, and...

As “education” becomes more meaningless, it’s achievements get more hollow and symbolic. Lists of books to be name-dropped – not read – as important because they’re on lists. Until they're dismissed for other books that reflect the latest set of feel-good whims passing as timeless wisdom. What does this matter to Dante in the 21st century?

Who makes the Great Book lists?

The answer brings us back to MLAE.

We've already looked at the repulsive Harold Bloom's epic con job - a pastiche list with no reflection that looks like grad students threw it together. Clinging like grim death to his Yale sinecure and lending "credibility" while that once-great institution sank into the morass.

But this is the caliber of "champion" the beast is capable of. The death spasm of MLAE and it's declarations of "Great Books" lists - where modernist atavism slimetrails after real artistic achievement through the carcass of tradition. All to appropriate the intellectual equivalent of stolen valor and cheapen genius at the same time.

The genius is real. Don’t mistake the greed and vanity-driven lies of the secular transcendent "elites" for those who tried to elevate the masses with accessible literature. Advanced "Liberal Arts" education is pointless as a mass activity, but the knowledge and wisdom contained within it is valuable.

Cultures need common threads to tie them together. Shared experience is the start, but like any relationship, this has to deepen in time. Actual great books - without the idiotic capitals - are a huge part of this. They provide the touchstones and shared references across generations that forms into national cultures.

William Michael Harnett, Music and Literature, 1878, oil on canvas, Albright-Knox Museum, Buffalo

Along with the visual arts and music, literary traditions are schools, mirrors, and glue - reflecting, teaching, and binding a culture together.

We don't all have to be experts in it, but it does have to be there and some of us do...

The whole point of having an academic establishment is to provide wise cultural judgments so everyone doesn't have to be expert. It should be natural for a publisher to turn to a respected English or Literature department for guidance. A lot of people still believe you can and will become angry when you point this out. We agree you should be able to - if you're going to sink the collective resources that the West has into academe, the least you can ask for are some reliable reading lists. Just not in the beast system.

But here's the problem. Their lists are painted over the remains of the good, the beautiful and the true. We can’t just cast the lists aside – the foundations of the West are there.

Take a look - here are the opening entries of the original Britannica Great books list.

It's not a bad introduction to the Greco-Roman heritage. You can quibble, but the big guns are all there.

Now here's some expanded 20th century from the updated version. In what universe does this indicate cultural health on the eve of the 21st century? Compare what this transmits to the ancient list...

If the literary canon is the soul of a culture, this shriveled, blackened wisp is crying out for an exorcism.

Now keep in mind, this moronic line-up is based on the childlike superstition that a book list can transform the nature of the entire human race. Pretend for a moment that you suffered a head injury and believed this...

What is this intended to transform you into?

A common beast system trick appears too - removing signs of logos. This was an issue that motivated the reissued Junior Classics series to go all the way back to the 1910s version - the '50s version had already started censoring Western Christian heritage. The "Great Books" started in the '50s, so they could leave out the Christian West from the jump. Here is the entirety of the medieval tradition. You're looking at most of the early Christianity and the Renaissance too.

Without the modern excrement it still stinks like a rotting corpse. Where's the soul?

The fake secular transcendence of the "Great Books" takes the legitimate greatness of the Western heritage, strips it of the conditions that made it great, then pumps back a degraded inversion that turns cultural suicide into posturing masturbatory ignorance.

The message is that we have to take up responsibility for our own heritage.

We tried outsourcing it to portentious liars that appeared to have "gravitas" - now the institutions are dead and we don't even have those self-parodies around for incidental comedy any more. We need canons of art and literature, but the what wears the skinsuits of the stewards seems to hate our heritage even more than us. This is only a problem if you still want to believe the beast's shopworn lies. Nothing wrong with lists... If you can separate the wheat from the tares and justify them.

So why read Dante?

1. Technical and aesthetic reasons

La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellvtello, published in Vinegia by Francesco Marcolini, 1544

Hand-colored woodcuts of heaven from the 16th century. The sublime structure of Dante's verse is matched by his cosmos. The Rose of Heaven is a powerful image of something that can't really be shown ditectly.

The Comedy is one of the greatest pieces of writing ever written by anyone anywhere. It's masterpiece of creative vision. The quality of the writing, the complexity and care of the structure, the range from cosmic to personal, the pure weird, genius originality of it. If you have any appreciation for the highest levels of writers' craft, it's one on the list that is a must read. The terza rima structure alone is sort of mind-blowing.

2. Profound influence.

Giotto, The Last Judgment, 1306, fresco, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

The Comedy set how late medieval Christendom saw the afterlife - including painters like Giotto, who knew Dante personally. The vision of Hell in the lower right with punished sinners and a huge devouring Satan borrows heavily from the Inferno.

Here's the close-up. Giotto is similar to Dante in that he gives the afterworld tangible form. It made their message easy to dismiss for self-pleasuring lies.

That may not have been the wisest idea in the long run...

Michelangelo's massive Last Judgment lin the Sistine Chapel came along almost two and a half centuries later. But he filtered Giotto through his own unique art. The wingless angels, Apollonian Jesus, and contorted musclemen are pure Michelangelo. But the basic radial orientation is the same. And the vision of Hell in the lower right...

Michelangelo, The Last Judgment, 1536-1541, fresco, Sistine Chapel

His art is hard to talk about. It is very powerful but very personal too. There's nothing else that really looks like it.

The vision of Hell doesn't have the same giant Satan, but Charon driving the damned and Charon judging them comes from Dante.

Rodin's Gates of Hell were a lifelong project that channeled the Inferno through his own warped imagination. The building it was intended for was never built but the piece has been cast in several versions.

Auguste Rodin, The Gates of Hell, 1880-1917, bronze, version in the Jardin du Musée Rodin, Paris

Rodin was supposed to deliver the gates in 1885 for a never-built museum. He never stopped working on them and many of his most famous designs are here. Including The Kiss and The Thinker.

Dante managed to integrate Christian eschatology with Classical metaphysics in a way that seemed as flawless as a fine watch. It's what the epochal mind who most influenced him - Thomas Aquinas - had worked through ontologically, but brought to life as only an artist can. Dante's poem is the literary version of Aquinas' Summa and the architects' Gothic cathedrals. An epochal expression of wisdom from an epochal age of faith.

The Comedy even changed how we write. We already mentioned how it was at the forefront in switching serious literature from a moribund second language to the full creative potential of living first ones. This leads into...

3. It's a Pillar of the West

In the before times, governments paid lip service to their cultures.

Chronologically, the three pillars of the West are the Classical heritage, Christianity, and the European nations. This forms over the Middle Ages into a cultural mosaic. Dante symbolizes and drives the switch from Latin and Greek to the languages of Europe. This makes him epochal. Like Shakespeare in English he establishes, defines, and is the best practitioner of the language all at once. In fact, Shakespeare is the only author we would place unequivocally over Dante - and even then not on every level.

4. Your future

Where did your world come from? Where is it going?

Gustave Doré, Dante and Virgil in the Ninth Circle of Hell, 1861, oil on canvas, Musée municipal de Bourg-en-Bresse

It's all connected isn't just an edgy thing to say - it's how things are. Basic Aristotelian causality. You don't get the culture that the West slowly built by committee or or wishes. It was a hard, grinding slog with the blood and tears balanced by towers of artistic achievement unprecedented in history. And that was the bedrock for organic, logos-based culture to grow like a Purgatory opposite the Hellish price. If you've had a comfortable life in the West - and a lot of other places - you've benefited from the material fruits of that hard road. Wouldn't it be nice to pass them on?

Robert Gallon, A Village Scene, 19th century, oil on canvas

Consider the horrors we've normalized at the hands of psychopaths. Really consider it.

That's four good reasons.

So how to read Dante?

For most of our readers, that means translations. And translations always mean more problems.

Translating extends the fundamental problem in communication - that no two readings are the same. Take these paintings of Beatrice - a complex central figure in the poem and Dante's poetic life.

Tomb of Beatrice Portinari (1265-1290), S. Margherita dei Cerchi.

Beatrice is usually connected to Beatrice Portinari - an Italian banker's daughter who married another banker and died young. The connection is made by Boccaccio - who knew Dante personally - but isn't substantiated anywhere contemporary.

Dante got the same mythologizing treatment in the 19th century as the Renaissance painters in the Arts of the West posts - so the elaborate tales need a grain of salt. Dante was very self-aware and blurred the line between his poetry, his poetic character and his real life. The Comedy is the best example, but not the only one. Beatrice is his guide to the beatific vision in Paradiso and the courtly love object and muse in his Vita Nuova. He never spells out what is real and what is poetic imagination.

Salvador Dalí, Dante Reawakens, 1964, original color woodblock print on paper, private

Dalí's print set is interesting. The Band finds his surrealism inverted and morally degenerate and his self-promotion an ugly form of beast dancing. But his skill as a designer comes through in his line and the unreality actually works for the mystical subject matter.

It was convention for a poet to have an unattainable love object to generate deep longing and sincere poetic feeling. It's why so much of it seems so skin-crawlingly gamma to us today. But it is unfair to judge with modern eyes. For the vast majority of medieval people "getting girls" was impossible to the point of inconcievable. Most marriages were arranged, and social propriety meant that the exceptions followed proper forms. Longing without hope of consummation was the norm in a way most modern people can't even picture.

Henry Holiday - First Meeting of Dante and Beatrice, 1877, oil on canvas, private

Not that poets were seen as particularly manful - they just weren't the obvious simps that they look like today. And no one simped in art like the Victorians.

There's no way to know how much Beatrice was a lifetime crush and how much poetic imagination. The way she is presented in the poems is unambiguous - inspiration like Petrarch's Laura with a metaphysical ability to inspire virtue by her chaste purity.

The longing in medieval poetry is complicated for modern readers. In the aristocratic courtly love tradition it was thinly-veiled sexual lust, and it is impossible to completely dismiss that from Dante. The difference is that his poetry is more overtly Christian and any physical passions more deeply sublimated. It's similar to what we saw in the Michelangelo post - carnal feelings suppressed into sublime art, only without the added moral complications of homosexual impulses. In both cases, the answer is a sort of Platonic beauty that spiritualizes carnal feelings.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Innocence, 1893, oil on canvas

It's what Bouguereau is going for here. There's something skeevy about some of Bouguereau's youths but there's none of that here.

The concept of Platonic love was badly distorted by modern Flatland and lies. A gamma will lie and call their attraction "Platonic" in order cope with the pain of the friend zone. That's not what it is.

Platonic love only makes sense is you understand that a) human nature is pulled between animal matter and divine spirit and b) morality is also objective and divine. The love of God is uplifting, spiritualized and not sexual. And God is also the source of morality - what Plato's originally called the Good is the eternal standard of God's will as we can comprehend it as something possible to align with. And once there is an eternal standard of Good that is comprehensible at least as something that must exist, Truth becomes what it "means" and Beauty what it "looks like".

We aren't going into the Vita Nuova - it isn't as good or profound as the Comedy. If you like Dante's poetry, it's still excellent. Here's a linked translation to see before committing to buying. Beatrice is presented as sort of savior - her death turns her into a beacon drawing him heavenward.

Elisabeth Sonrel, Scenes from Dante Alighieri's "La Vita Nuova", early 20th century, oil on panel, private

Here's the text of a sonnet from the second to last canto. Dante is turning his material loss into anticipation and incentive to work towards his future salvation.

Canto 31 concludes the Vita Nuova and is worth quoting because it comments on the sonnet.

After writing this sonnet a marvelous vision appeared to me, in which I saw things that made me decide not to say anything more about this blessed lady until I was capable of writing about her more worthily. To achieve this I am doing all that I can, as surely she knows. So that, if it be pleasing to Him who is that for which all things live, and if my life is long enough, I hope to say things about her that have never been said about any woman.Then, if it be pleasing to Him who is the Lord of benevolence and grace, may my soul go to contemplate the glory of its lady—that blessed Beatrice, who gazes in glory into the face of Him qui est per omnia secula benedictus.

In real life Dante was betrothed to his future wife as an adolescent in 1277 and married her in 1285. They had at least four children but he never mentioned his family in his poetry and they do not appear to have followed him into exile from Florence in 1301. Beatrice is the subject of all his feeling of longing.

In the Comedy it's even more literal

Canto 26 of the Paradiso starts with St. John the Evangelist examining Dante on the nature of love. There's so much here. Dante is describing a Neoplatonic concept of material goon emanating from the Good - or God's comprehensible nature. He then links this to John's Gospel, where the philosophical concept of logos is used to describe Jesus the Logos.

He must have skipped the memo that this way of thinking had been lost until the Renaissance...

The beast has been degrading and underselling the medievals since the Renaissance. Remember the super-great Great Book list from Britannica? The even-greater 1990 addendum included two references to the medieval era - references, not books from - Johan Huizinga's Autumn of the Middle Ages and G. B. Shaw's Saint Joan. That's correct - a 1923 reimagining of the Christian mystic and national icon as a modernist political reformer. And a legitimately great 1919 Dutch history that happened to be a major piece of the whole fake modern Progress! out of the backwards Middle Ages historiography.

Dore, Canto 26

Ficino's complete Plato wasn't available, but there were Neoplatonic themes in medieval thought and Christian metaphysics used Neoplatonic structures where appropriate. More in the East, but in the West as well.

The Renaissance myth was that medieval philosophy was purely Aristotelian before being enriched by Renaissance Platonism. The reality is... different.

There were waves of ancient learning that washed over medieval Europe as needed. Start with the formation of the medieval West out of the ancient world - like the Neoplatonic framings in the theology of the Fathers of the Church. Or the emergence of Christian art from Classical. Here are some of the vectors that followed.

Skellig Michael Monastery, between 6th and 8th century

Irish monasteries on the edge of Christendom launch the first wave - copying texts and carrying their communitarian religious vision back into pagan Europe. Remote island Skellig Michael is a well-preserved example of these unlikely bastions of learning.

Until they found a suitable supporter in Charlemagne - the Frankish Emperor looking to boost culture on a wide scale. What historians call the Carolingian Renaissance was the result.

Muḥammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (865–925), Kitab al-Mansouri fi al-Tibb (The book on medicine dedicated to al-Mansur), written early 10th century.

Top - late 12th century Latin by Gherardo da Cremona; bottom - 15th-century Arabic version.The Renaissance of the 12th century was driven by economic growth and translation of Greek and Arabic scientific texts. The big difference from the later Italian Renaissance was that it was more technically-oriented then arts and culture, but that's actually more legit. And it did bring us Romanesque architecture. That's the world captured in the next century by Aquinas' epochal mind and Dante's epic verse.

This is the sort of thing that the Europeans were interested in. Al-Razi was known for medical, philosophical, and alchemical works. This one became part of the medical curriculum in medieval universities.

Back to Paradiso 26. When Dante is talking with John he's temporarily blinded, and it's Beatrice that has the power to restore his sight. What we end up with is a beautiful summary of ontological ascent to ultimate reality through faith and revelation - the only ways to know at that level. Starting with the "philosophical arguments" to Scripture to grace.

This is true Platonic Love. The elevation of mind, then soul to the Good and then God through the intellectual appreciation of beauty. It's the basis of Christian aesthetics and natural theology and what Bonaventure would call the mind's road to God. Forget friend-zone coping - the relation to the sin of lust is diametric opposite. Dante spelled it out with his capital letters.

Love is attraction to the good, the beautiful and the true as

the path to The Good, The Beautiful, and The True

Gustav Doré, “Beatrice and Virgil,” The Doré Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy

This cycles back to the Vita Nuova and the blessed lady that he needed to be capable of writing about more worthily. The chaste courtly love for the living Beatrice becomes a Christian Platonic love for the blessed Beatrice that completes his own ascent.

Not just in canto 26 either - if Virgil represents the higher level of abstract reason in the ontological hierarchy, Beatrice is the gate to ultimate reality.

Our Fallen material nature complicates this binary moral distinction. Not the distinction itself, but the biological and biblical imperative to reproduce sexually. That drive Dante is sublimating gets power from somewhere. We know empirically, by fruits that we judge with our senses. And there is beauty in creation. Beatrice is an allegory - an ideal - for a perfect form of Christian love that we aspire to rather than decide to just do.

Auguste Rodin, The Eternal Springtime, 1884, white marble, Museo Soumaya at Plaza Carso, Mexico City

Inspired by Paolo and Francesca for the Gates of Hell, but rejected too cheerful and clashing with the rest. The beauty of your spouse is where the two overlap in the most positive way.

The whole thing falls apart once open sexual competition is introduced into everyday life for reason that should be beyond obvious.

That's Beatrice. We brought her up because we were looking at the problem with translations as an extra heavy example of a basic problem with communication in general. No two readings are the same. Everyone pictures the simplest story differently, let alone complex ideas.

Paintings let us see this because an illustration is a personal interpretation made visible to everyone.

Cristóbal Rojas, Dante and Beatrice on the banks of the Leteo, 1889, oil on canvas

Lajos Gulácsy, The Meeting of Dante and Beatrice, 19th century, oil on canvas

Carl Wilhelm Friedrich Oesterley, Dante and Beatrice, 1845, oil on canvas,

Henri-Jean Guillaume Martin, Dante meets Beatrice, 1898, color lithograph

Beatrice guides Dante in Paradiso, 14th century miniature

Salvatore Postiglione, Dante and Beatrice, by 1906, oil on canvas

William Blake, Beatrice Addressing Dante from the Car, 1824-1827, ink and watercolor

Ary Scheffer, Dante and Beatrice, 1851, oil on canvas

Giovanni di Paolo, Charles Martel on the vicissitudes of heredity, around 1450, manuscript

William Dyce, Beatrice, 1859, oil on panel

Henry Holiday, Dante and Beatrice, 1883, oil on canvas

Cesare Saccaggi, "Incipit Vita Nova" - Dante, 1903, oil on canvas

What does Beatrice even look like?

Translation extends the problem with another layer of vagueness. It's not your personal reading of Dante that you picture, it's your reading of the translator's attempt to put his reading in another language. It's actually a two-part problem - the translator's subjectivity and the linguistic switch as barriers.

Languages are structured differently, making word-for-word translation impossible. Words don't have exact equivalents in different languages and different grammars have different orders and rules. Poetry is worse, because the play and rhythm of the language is part of the effect. And Dante's poetry is a pain.

Initial N with Dante writing the Divine Comedy in his study, from a 14th-century manuscript of La Divina Commedia, Biblioteca Guarneriana, San Daniele del Friuli

Dante wasn't just inventing the language. He was doing it in a complicated structure called terza rima. We break it down below. He appears to be the first to use this - Petrarch and Boccaccio both use it and Chaucer brings it to England later in the 14th century.

Dante's meter is also different to modern English ears used to iambic pentameter. The Comedy is mostly hendecasyllabic - 11 syllables per line with the accent on the second to last.

The little description of the structure of the Comedy shows how impossible a full translation would be. According the the Infogalactic link above, hendecasyllabic verse is the standard in classic poetry. But terza rima is Dante's invention and something that locks the entire creation into a single unifying order. If we think of Dante as a poetic equivalent of the Summa Theologica or the Gothic Cathedrals, the structural unity of the terza rima is like Thomistic logic or the rib vaulted system of architecture. A higher order that brings the whole thing closer to the abstract ideal perfection that brings beauty towards Beauty.

Here's a look at it using the passage from Paradiso canto 26. We've replaced the last stanza in the quote with the actual next one in the Comedy because terza rima flows from stanza to stanza. One alone doesn't show it, and a longer sequence makes it clearer.

Each stanza is three lines, with the middle of one rhymed by the first and last of the next. We've higlighted the rhyming words to make the meter more visible. It maintains this throughout the entire trilogy - the only exception being the end line of each canto. To close off the sequence, each canto concludes with a single line stanza that rhymes with the middle line of the one before it. The end of canto 26 looks like this -

So every person's reading of a book is different. Every language presents and frames the world differently from the others and Dante's world is over 700 years old. And his poetic structure is a masterpiece, but also impossible to translate while maintaining any semblance of fidelity to his meaning. It's maybe why Dante is so frequently translated - the impossibility of "getting him right" means he's freer to make your own.

So the answer to the best way to read Dante is in the original if you can. If you can’t, then you need to pick "the best" translation. Meaning, the one that fits with what you want out of the book. And that leads to the next question -

Why read poetry?

Wedgwood & Bentley, Five Muses, design attributed to John Flaxman, Jr., 1778-1780, jasperware plaque, Brooklyn Museum; from left: Erato [Love poetry] with a kithara, Melpomene [Tragedy] holding a dagger. Calliope [Epic poetry] writing, Thalia [Comedy] holding her comic mask, Urania [Astronomy] next to her globe.

The answer is obvious in classical theory. Here are Muses of four poetic genres and astronomy. Urania was always special because of her connection to the heavens. She points to the heavens with that old Renaissance gesture of divine enlightenment to symbolize the wisdom that comes through in the others. Poetry gives form to higher ideals by transforming language with order and grace. Like any art form - beauty is a material reference to Beauty that leads us back to Logos.

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons and Thomas Bentley, Calliope, Muse of Heroic Poetry, 1768-1780, blue jasperware, Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, WI

The Muses were popular with Wedgwood and Neoclassicism in general. Calliope was the Muse of epic or heroic poetry and is closest to Dante. Thalia - the Muse of comic poetry - is there too, but despite the name, the Comedy is more an epic allegory.

Part of Dante's originality was his bringing classical ideas about the arts into Western Christian terms. Christian epic enlightening in exquisitely structured vernacular Italian.

Classical ideas about poetry don't carry much weight in the beast world. Poetry in general is a hard sell - the Band's theory is that art and poetry were deliberately taught in repellant ways to kill them as cultural vectors. Anyone reading this is obviously open to other points of view. For someone like Dante - who has been translated so many times and for so long - there are many reasons.

There’s professional Dante - the whole world of Dante studies and academic Dantes in many different areas.

Quick result from a subject search in the public catalog of the world's largest university library. Harvard is an easy proxy for academic attention over time. The materials aren't accessible, but what is in the collections is.

The legitimate stuff here looks for information about the text and it’s world – history, symbolism, influence, etc. Translation is part of this – the more accurate the better.

The Digital Dante Project at Columbia is an excellent example of Academic Dante. It’s an organized website that presents Dante’s work and related materials in the original and different translations. The site as a whole isn’t bad – the commentary performs its postmodern narrative service but is informative at times. It's worth a look if you can read selectively and are interested in Dante and his world.

The English translations included here are Mendelbaum and Longfellow. The way they're broken up is annoying to read but good for getting a sense of things. In our opinion, these are the best translations for different reasons. We prefer Longfellow personally, but Mendelbaum has it's strengths as well.

Here's Mendelbaum. As far as we can tell, it appears to have been the standard Academic Dante for a while. Mendelbaum was a poet and professor - his Dante is clear and scholarly without losing too much of Dante's singular power.

Of the six versions we can comment on, Longfellow's translation is the best in our consensus opinion. He was also a scholar and poet, but on another level artistically. Plus he's very faithful to Dante's word choice. He actually captures some of the eldritch strangeness of the medieval Italian. Different structure, but similar aura. Neither attempt the terza rima.

The best way to compare these two is directly. Here's one passage from canto 3 of Purgatorio with the original Italian and the two translations. In it, Dante and Virgil have come to a steep cliff and are looking for a way up.

Now break it down line by line and look for patterns of difference. We've attempted as close to a literal translation as we can for readers unfamiliar with Romance languages. It's not 100% - we're not linguists and Dante takes liberties with the language. But it's more precise than either translation, and you can instantly see why translating poetry is so hard. It sounds retarded because Italian and English use different word orders and grammatical structures. And who is to say a slightly different phrasing or synonym isn't better?

So the translator has to take the meaning of the words and then put them in a way that captures something of the experience of the original. Here is the kicker - they're mutually exclusive, but the better you can do on both, the better the overall translation.

We find the Longfellow translation superior for both the fidelity to Dante's word choice and structure. Even if you don't know any Romance languages or Latin, you can see it by looking at the example here. It sounds more arcane, but you don't get much more arcane than Dante. And he was writing in the Middle Ages. Longfellow is also a superior poet, and while not at Dante's pinnacle, close enough to turn a phrase. For the reader seeking as much of the majesty that puts the Divine Comedy in that uppermost pantheon of all-time writing - this is as good as we've seen in English.

Bringing us to what would be the main limit - Longfellow is deliberately writing in a sublime 19th-century poetic voice. Some people have been sufficiently benumbed to the aesthetic power of art that this is a barrier. If that's you, Mendelbaum is a fine second option. You can see in the selection that he's no slouch as a poet - his language is closer to de-moralized later 20th-century academic without giving up too much aesthetic force.

It kind of looks like this...

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Dante, oil on panel, 19th century; Pierre Aubert, Dante and Ovid, bronze, 20th century

This explains why he's popular with academics - he actually isn't more accurate. What he is is a good translator who nailed that late 20th-century mirage of disinterested "neutrality". And our former number one choice before reading Longfellow - now a worthy number 2. We get why the Digital Dante site included them.

For many readers, fidelity is less important than enjoyment. Obviously both Longfellow and Mendelbaum are excellent reads as well as very faithful. But once you are strictly concerned with story, the translator's style is even a bigger factor.

Many people first met Dante in the uber-successful Penguin translation by multi-talented English writer and eccentric Dorothy Sayers. It must be the best-selling English Dante. It's not considered up to academic standards of fidelity, but it is highly readable. Even more accessible than Mandelbaum. Sayers is a really good writer and clearly put a lot of herself into the translation.

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, translated by Dorothy L. Sayers, published by Basic Books, Inc., New York, 1962

One of the best things about the Sayers Inferno is the long introduction to Dante and his world. It and the glossary are especially good for readers new to medieval literature or tackling Dante for the irst time. Click for a link to her Inferno, including the introduction.

Now to wrap with the inspiration for the post. The Band has recently come across some new editions of Dante that are notable but very different.

The first is the modern retelling by Alasdair Gray, a late Scottish poet. The goal is to put Dante’s impact into more contemporary language. Not really a prose summary but modernized enough to not really be a translation either.

Gray calls it "Englishing" which is more twee than helpful.

A work like this is more like a collaboration then translation. Gray is a poet, so writing in verse is natural. But he does away with the terza rima and the complex structure

This frees Gray to transform Dante’s images in the way he finds most effective. Which also means making them his own.

Start with a look at the passage from Purgatorio we broke down up above.

This is typical go Gray's transformations - it's more substantially reworded than a typical translation, but doesn't otherwise de-moralize or invert the text. We found it to be much more enjoyable and worthwile than we expected. Though to be fair, it's not as if recent "adaptations" of things have given us cause to be optimistic.

We can understand what he's doing by looking at the opening lines of the Comedy. Here they are from the main translations, the original, Gray, and the page from Sayers showing the some of the supporting material that makes the Penguin so good for new readers. Chapter summaries and chronologies as well as the big intro and notes.

As expected, Longfellow is closest, Mandelbaum the more "neutral" late 20th-century version, and Sayers deviating more from the original but nicely telling the story. Note how Gray makes the poem feel even more personal - like a confessional. Not Dante as a life crisis because he is faithful to the supernatural elements. But the personal side of Dante's allegory dialed up to accentuate the applicability to what reads like Gray's own existential quest.

This comes through in the illustrations for the cover and in the text that Gray also does. Instead of showing Dante in the Dark Wood as a scene, the abstract close-up makes you think of a person - maybe yourself - fumbling their way. It sets up the personal feel in what makes no bones about being a personal work.

As a strategy, this is honest. We started by noting that translation is a personal reading - once you remove fidelity to the original as a goal, the subjectivity moves to center stage. By owning this from the start, Gray makes it easy to put aside the personal idiosyncrasies like "kirk" for church and enjoy it for what it is - an expert retelling of a classic tale.

The expert part is important. There are so many translations of Dante - there has to be something to make you want to read one in particular. Gray's liberties with the text include considerable expurgations. Here's an extended quote of Dante spotting Beatrice in the Empyrean Rose that capturesthe aesthetic quality in his more personal language and how much shorter his version can be.

Gustave Doré, Beatrice enthroned in her place in the celestial rose, around 1868

Gray is like most readers in that he was drawn to the first book – his Inferno came out before the other two and Sayers never finished her Paradiso. Readers have always had a prurient interest in the torments but that has intensified in modern times. It's inevitable. Flatland only has secular transcendence - there is no possibility of real transcendence, so the moral progress of Purgatory and Heavenly rewards fall flat. To appreciate those we need to be able to see that the True, the Beautiful, and the Good exist.

But one thing Flatland can do is wallow in torture. All the better if we can cluck about “superstitious” medievals. Better still if panting obesely through a mask.

Botticelli, Map of Hell, manuscript painting for Dante's Divine Comedy, 1485, Vatican Library

The Inferno is fascinating – but it may as well be Minecraft without the chain of logos connecting it’s dark vision up the ontological hierarchy. To his credit Gray doesn’t shine away from the less infernal regions.

We liked Gray more than one might expect from traditionalists. He’s a very good writer who obviously loves Dante. He is more accessible than Sayers, but also more modern in sensibility. He is a fine choice for someone familiar with Dante already or REALLY resistant to old-timey writing. And he is a shining example of Dante's place in the culture of the West - still stimulating personal response after over 7 centuries.

If there's a problem, its a general one with modernity as a whole.

The strength of Gray's telling is how he makes Dante personal as well as modern. But all the variations and critiques that modern culture is obsessed with need familiarity with the original. This isn't radical - you can't appreciate a variation on Dante if you don't appreciate Dante.

He's someone who echoes through time - if you have ears to hear them.

Modernizations and adaptations are fine, so long as there is the original to go on to. We’d have enjoyed Gray and respected Dante less had we not been familiar with the original and able to appreciate what he was doing.

Otherwise you only have a good story. And while there's nothing wrong with that, it's not Dante...

If Dante is to continue as cornerstone of the arts of the West and inspire the Grays of the future, we need quality copies of Dante. And that brings us to the last part of this post - combining Dante and the Band's larger interest of cultural rejuvenation through logos of which Dante is part.

Producing premium quality leather-bound books at a standard that already supersedes past popularizers Franklin and Easton Presses.

In 2021.

For champions of cultural renewal and vitalization like the Band... let's just put it this way.

Castalia Library and its sister imprint Libraria Castalia are relatively new, mainly subscription-based publishers of premium and ultra-premium books. From the website, they are imprints of Arkhaven Comics who the Band has plugged before.

That does seem a weird place for expensive literature - we plugged their comics. But there is also a link to Castalia House - a boutique European publisher - but there is no obvious mention of the Library or Library on the House site. In fact, the whole site could use a make-over - it looks like something being stretched beyond it's original purpose. Because if the Castalia Library Divine Comedy that we have is typical, these books deserve presentation that does them justice.

Because the Library Dante is gorgeous.

There are two imprints operating on a subscription basis - the premium Library and the ultra-premium Libraria. Here are links to the Castalia Library and the Libraria Castalia. We have not seen a Libraria volume - if the difference in average price of $100 vs. $250 is justified, they must be works of art. This kind of exclusive publishing is done in fixed print runs, and surplus books are offered first to subscribers then to the public. This raises the price to $150 and $500 respectively; worth it for the Library Dante, can't say for Libraria. There are still some of both available if you're curious - click for the specs.

They haven't been around that long, but the nine bi-monthly titles to date are a mix of choices from their own catalog and selected works of canonical literature. We suspect that the latter is where they will orient in the future. The exciting thing is that they're not just following a list cribbed from some cypto-marxist English department. The books look to be chosen for historical significance and current relevance. Consider this an endorsement for as long as they stay the course.

François Lafon, Dante and Virgil on the Banks of Purgatory, 19th century, oil on canvas, private

Because there are two critically important things at play here. Producing expensive, quality books in a post-literate age seems counter-intuitive until you perceive how fast the sun is setting on the Liberal Enlightenment mirage. There never was a time when the masses were erudite. But there were always durable copies of important literature.

The beast system came with mass dumbing down and the destruction of social bonds. Financialization of just about everything was a race to the quality bottom because "cheap". If people have any hope of valuing culture, they need to know about it. Accessibility before appreciation is even possible. In a disposable world of idiots and dancing lights, where do you learn?

Eduard Rüdisühli, Dante and Virgil Enter Hell, 19th century, oil on canvas, private

If you can't take a metaphysical journey with another pantheon-level poet, where do you turn?

A book like this is a gate to accessibility and appreciation. Physically it is lovely - the binding is excellent – the only irregularities being the uniqueness of hand craft. The paper is a nice weight, white and clean but not overly bright, and gilded on the edges. The gilding is sturdy and doesn't mar or scratch easily. The cover illustration looks better than the picture, and after a full read and some quote mining, there is no visible wear. The text is sized and spaced nicely - needless to say it reads well.

When opened there was an initial cracking sound, but only the once. Afterwards, the pages just fall open and are easy to turn. Supple but rugged. The book reminds us of 19th-century volumes, when the binder's craft was highly refined - almost monumentally solid and highly functional. It is fairly heavy, but not overly so and is easy to handle. Overall, if the paper is as advertised, it looks built to last at least 1000 years - more if kept safe and dry.

Dante Alighieri, Divina commedia with commentary by Cristoforo Landino, printed in Venice by Pietro Quarengi, 1497

A set of Italian woodcuts from this edition of Dante provide illustrations. They visually complement the type and look cleaner than in these originals. There's a similar feel of clean contrast. In fact, the pictures remind us a bit of Gray - not the style, but the way the line drawings suit the text so well.

Printing made books cheaper and more common than manuscripts, but they were still pricy. According to this site, the 1497 Dante sold for one ducat when four or five ducats per month was adequate income and ten ducats relative affluence.

The choice of the Longfellow translation is the capper. It's strengths are maximized in a publication like this where lofty poetic language feels right at home. It doesn’t include notes or the Italian text – it’s an heirloom copy not an academic edition and readability and accuracy are perfectly in balance.

Attributed to Cesare Zocchi, Dante, bronze, 19th century

Other than some Inferno excerpts, we had actually never read the Longfellow translation. Part of the positive impression of this book comes from seeing how good that is. But part of it is the look and feel. The reader's experience. We already noted how he best captures the eldritch grandeur of Dante - that goes up a level in a bookmakers' tome that is such a pleasure to read.

This statue of Dante appears to agree.

If you want the original Italian, we've included the link to Digital Dante. If you want an informative introduction and copious notes, we've included the link to the Sayers Inferno. If you want a personal modern introduction to Dante, check out Gray. And if you want to make sure your descendants will be able to appreciate all the same, Castalia has you covered. For more than Dante...

That's a crack at a logos-based essay-review. We got to look at some recent Dante, scale out to why to read Dante, and scale further out to the importance of canons. Because there are always canon. Best make sure ours point the right way...

Gustave Doré & Kalki, Color modifications of an 1867 Public Domain image by Doré, of Dante Alighieri and Beatrice Portinari gazing into the Empyrean Light, 1867

No comments:

Post a Comment