Concluding a three-post journey through beauty, faith, and the necessity of logos with Stephen R. Donaldson's epic fantasy The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever.

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check regularily and it will be up there.

One more trip to the Land, where The Chronicles - like High Lord Mhoram - save the best for last.

There are a lot of interesting things on the go around Band HQ and we don't want to lose sight of The Chronicles or the positive posts in general. This will complete the Covenant trilogy - not sure what will come next. It's developing, but there'll be something. Whatever it is, it shouldn't take this long to do.

For now, there's this. The last book of The Chronicles is the best. Full bias disclosure - it's probably our choice for the best single all-around fantasy novel we've ever read. It's not a literary masterwork like The Silmarillion and the usual Donaldson problems linger - though if you've read this far, they aren't really problems.

"Bests" are always subjective and limited - we find them most useful as pointers when we trust the recommender. We rate The Power that Preserves so highly for these reasons.

It's an emotional blast furnace ending in indescribable catharsis

It shows the necessity of logos so perfectly that any closer crosses into allegory.

The plot is nearly flawless - all the major arcs and issues wrap up.

You can always quibble. We'd change a few small details, but we aren't convinced they would make it a better book - just a little more to our liking. The stilted language and Tolkienisms are still there. But if there is one thing the Band has learned it's to avoid claims of abstract perfection in a fallen world. And with that caveat, this is close enough.

The tale is grim - without the wild promise and exuberance of the Land that comes through at times in The Illearth War. But the Logos journey and main thematic and character arcs are completed so perfectly that the harder, starker focus is necessary. If anything, the stripped-down narrative focus and near-flawless plot structure bring The Chronicles closest to the feel of Greek drama - where events funnel inexorably to two impossibly cathartic finales. Covenant and Mhoram's paths lead through paradox and multi-level logos - from the SSH to the necessity of faith - resolve flawlessly through growth and understanding. And the ending is pitch perfect.

It is the third book in a trilogy and the third post in a series of three. The Power that Preserves doesn't make much sense without reading the first two.

The first two posts on the Chronicles are linked here

They can be found any time on the Truth of Culture page linked up above.

If there is a "flaw", it's that Mhoram's climactic showdown might overshadow Covenant's a tiny bit. But that's ok - if we were stranded on a desert island and could only have one fantasy chapter, it would be "Lord Mhoram's Victory". And the strength that allows him to surpass all previous limits and turn the war against an invincible foe by personally taking him out in an absolute toe-to-toe slugfest comes from his faith in the Creator and Covenant his Logos.

Besides, it wouldn't be Mhoram if there wasn't an improbable first place finish. And it's hardly an issue since the climaxes are linked. And the grand finale is a powerhouse. All the pressure, tension, emotional intensity, and fumbling growth reaches a searing conclusion.

Iconic 80s Maxell Blown Away campaign

Reading The Power that Preserves after the first two books is the readers' equivalent of watching 300 or listening to Maxell tape in the 80s.

First the usual disclaimers. There's nothing like a rape or incest theme, but the story can be grinding and bleak. The tragic end of Lena completes an arc set into motion in Lord Foul's Bane and it is legitimately really sad. But Covenant doesn't commit new evils and suffers for his old ones. If the first two books weren't a problem, this won't be.

A ton of characters die, but some key ones don't. Along with Covenant and Mhoram, Quaan, Lords Amatin, Trevor and Lorya and their children, and the rest of the inhabitants of Revelstone survive the siege. Mithil Stonedown, Bannor and most of the Ramen make it through. There's enough death to feel the weight of the events and enough survival so that the victory doesn't feel too pyrrhic. Making you feel has been a huge plus of The Chronicles all along. The Power that Preserves brings it home.

Douglas Beekman, The Siege of Gondor

One more time... The martial characters contest the Siege of Gondor while the Ringbearer and his truest friend and companion journey to the heart of Mordor. They manage to get to the watcher at Cirith Ungol by using a secret passage.

But if it's not a problem yet you won't even notice. The tone is so different here.

The Power that Preserves

There are two main narrative arcs - Covenant's arrival in the Land near Mithil Stonedown and journey to confront Lord Foul, and Mhoram's defense of the siege of Revelstone.

This post is the conclusion of the set - both in The Chronicles and this trio of posts. That means the pathways are pretty much set in terms of how we can approach this. We will start with the Logos structure since that's what makes The Chronicles so notable. Then, since the story splits to follow Covenant and Mhoram to the completion of their respective stories, we'll follow the two arcs.

Start by revisiting the logos structure from Lord Foul’s Bane - it's tied into the complex applicability of The Chronicles. We discovered that the Land more or less conformed to the metaphysical structure of our ontological hierarchy. Including a rough approximation of the connected epistemological modes. This means that deep truths in the sub-creation - the Tolkien term for the fantasy world - will line up with the same in our reality.

The Land had a Creator who casts down Foul outside of time and sends Covenant into the world to save it. The relationship isn't exactly Christian as much as it is applicable to the real world where abstracts aren't visible.

Donaldson uses the "Arch of Time" to refer to the boundaries of Creation. This draws the distinction between the temporal material reality and the immortal abstractions. A distinction that we are increasingly aware is critically important to understanding our own ontological position. What we call secular transcendence.

Lord Foul is an abstract-level entity trapped within the world. We don’t know his exact connection to the Creator – if he’s a created entity like Satan or a slightly lesser co-eternal. In any event, he occupies the place of Satan in reality – an immortal evil that is the ultimate power in this fallen material world.

This becomes clear when we see his home.

John Martin, Satan Presiding at the Infernal Council, 1823–1827, engraving for Paradise Lost

Martin's engraving of Satan's palace hints at the eerie geometric perfection of Foul's Creche. The gelid green ice and flawless simplicity do a good job at capturing the horror of a world of temporality, change, and finitude to an abstract, literally immortal entity.

His vast, private halls are flawless and empty. The company of mortal beings - even allies - is intolerable. The frigid cold is also a desire for stasis and immobility.

It doesn't make him sympathetic or excuse his depravity and sadism, but it's a sharp insight into Dark Lord psychology.

And when Covenant finally beats Foul down and strips his enchanted shell, his powerful material form has a flawless classical perfection.

The ontological otherness of this being comes through with abnoormal clarity.

Until we finally reach Foul's Creche, we only see the conflict between the material beings in the Land and the abstract immortal evil of Foul from their - or our - perspective. This inexorable, unstoppable force that steamrolls any notion of heroism, strategy, or luck. Something so virulent and ontologically beyond us that simply recognizing it proves the necessity of Logos.

It's interesting to see it from his perspective. The material world as a nightmare kaleidoscope of flickering beings being born and dying, constant change, chaos, entropy... We can't imagine what a monstrous, eternal torment the material restrictions on Foul's abstract nature must be. His vast frigid, flawless geometric palace is his effort to surround himself with some approximation of his native unchanging perfection.

The Creator is absent by necessity. He is akin to ultimate reality or God in our world in that he is only knowable by faith.

Although he does make a brief cameo at the end and clarify a few things.

The way the Logos structure plays out is based on applicability. This is a Tolkien term that we started using in the Silmarillion posts that we really like. It refers to how a "sub-creation" conveys truth or logos. And a sub-creation is the word he used for a fantasy story that conforms to reality but simplifies to make some truths clear. It actually applies to all sorts of imaginative fiction.

Applicability refers to the parallels between the logos in the sub-creation and in reality. Not the same - that's allegory of symbolism. But fundamental truths that are recognizable and carry over in important ways.

The Chronicles are definitely a sub-creation as Tolkien defined it. They map out the necessity of Logos in a fallen world more obviously that it appears in reality. On the most macro level, the plot describes the same moral opposition between the will of God as manifest in Creation and evil of both passive and active types.

Grant E. Hamilton, To begin with, 'I'll paint the town red, published in Judge Magazine, January 31, 1885

Passive evil is the Fallen nature of the world whether we think of it in Biblical terms or the indeterminacy of discernment and entropy in morality and nature. Left alone, things decay and die,

Active evil is the immortal lord of this fallen world. The metaphysics are beyond us, but the combination is insurmountable for mortal beings.

This combination is behind the necessity of Logos .

Any logos-facing sub-creation of any quality will have a lot of moments of applicability to different things. The whole tragic arc that cut across The Illearth War that we've called The Sins of the Father is a clinic of applicabilities. But there is always a primary applicability. In The Silmarillion it was the integrated natures of reality, history, and representation. Or ontology and epistemology - a picture of what we can know and how we can know it that is exactly consistent with our own ontological hierarchy. This is because The Silmarillion and the ontological hierarchy both truthfully represent the nature of reality.

The truth is true. And that makes it consistent.

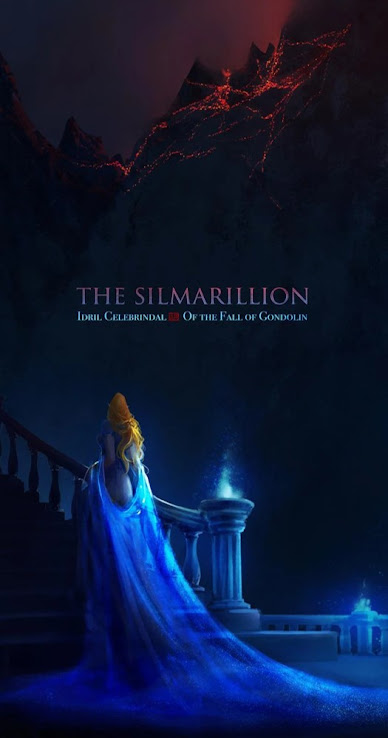

Interesting take on The Silmarillion from contemporary artist Yidan Yuan. Some of the interpretations are a bit anime-emo for our taste, but some are really good. The light captures the moment before the horrifying destruction of Gondolin. Idril is one of the few who escape.

On the surface, comparing The Silmarillion and the ontological hierarchy seems silly - one is a brilliant composite literary masterpiece and the other a concise diagram of our being-in-the-world. They're even derived from completely different directions and sources. But they are perfectly consistent with each other because they both accurately reflect the same reality. Like any truthful representation.

The primary applicability in The Chronicles is the

necessity of Logos in a Fallen world.

This is shown on three different levels at once. Here is the original breakdown from the first post.

The Land externalizes things that are internal or invisible in reality. It what Tolkien does, just in a different way.

Covenant shows us the necessity of Logos on a personally relatable level. He personalizes what the Land demonstrates. Together, these illuminate the real-world applicability.

This is complicated by Covenant. He is the protagonist who acts out the necessary changes for us. That's the personalizes part. But in the Land he is also applicable to the real Logos. He isn’t the same as Jesus any more than the Creator is the same as God, but the roles are applicable. Despite the differences, they apply in a way or ways that help us understand something about Jesus or God better.

But the result is that he is applicable on the personal level and on the externalized Land level, and inhabits a fictionalized version of real world. This ties the different levels together but can create some confusion in his role. Of course Jesus was a person and the Logos as well, but Covanent isn't an Incarnate God. And Jesus didn't personalize the need for Logos through his repeated personal failures.

The first thing we need to do is break it down better. Now that we've finished the trilogy, we can look back over the whole structure. Start by addressing the problem of "the real world".

The confusion comes from the relation between the Land and Covenant's world in the book and our reality as readers.

Applicability makes us aware that the essential distinction is between the sub-creation - in this case The Chronicles - and the real world that it applies to.

This means that we can't fudge the difference between the real world and the real world in the story. Everything in the book is potentially applicable to our world.

We still have the three kinds of applicability, but we now know how they interlock. The Logos structure in The Chronicles is applicable on the externalized level of the Land, personalized through Covenant and other characters, and invisible but necessary in Covenant's real world.

Here's the more complete diagram of what is going on on the sub-creation side regarding the applicability of the necessity of logos. We fill in what happens to us when we read.

There is the invisible applicability of Covenant's world and the externalized applicability of the Land. Both are personalized by Covenant through his own journey towards grasping the necessity of Logos.

In the real world, it's his increasingly hollow, insect-like materialist survival. Without family, art - life. In the Land, it's his mix of cowardice and moral bankruptcy that has him miss all the externalized truth, heath, and beauty.

This applicability breakdown is more carefully worked out than the version in the Lord Foul's Bane post, but it isn't significantly different in content. Mainly because that post didn't really consider the next subdivision. Here's where it changes.

The Illearth War complicates how applicability is personalized by adding new characters. Elena, Troy, and Mhoram all illustrate some aspect of the basic necessity of logos journey that Covenant is on or embark on similar from a different perspective. Points of view shift - Troy's amusement at seeing Covenant struggle with vertigo in on the far side of the great hall in Revelwood is a good example. And there are all kinds of parallels and oppositions between all four of the main characters. Even Bannor becomes the other side of an opposition with Covenant for Elena and Mhoram to contemplate.

From an applicability perspective, Covenant's presence in a clearly real Land creates a rift because his different roles collapse together.

On a story level, he is a character in the Land, where he brings personalized applicability to that part of his Logos journey. The necessity of Logos in the Land is externalized so he personalizes it differently than when he is home, but he is still a character having experiences. Other characters interact with him and to him when he isn't present.

His personal failures in the Land are the same as in the real world - they just play out in a way that reached him viscerally.

At the same time, his white gold is applicable as an externalization of the presence of Logos in the real world. And as is often cited, he is the white gold. While he isn't a "Christ-figure" in the traditional literary trope sense, he is metaphysical entity sent by the Creator and applicable to Jesus in the Tolkien sense.

The original Invisible-Personalized-Externalized applicabilities from the first post.

We see the conflict repeatedly in the discrepcncy between how how people in the Land react to Covenant and what it going on inside his head.

Carl Bloch, detail from Jesus is Found in the Temple, oil on canvas, Museum of Natural History, Copenhagen

It is true that Jesus is the Logos and a character in the Bible - that's the essence of the Incarnation. But Jesus the character is clearly aware of his exceptional nature, and isn't also personalizing a journey from fallen darkness to the awareness of the necessity of Logos at the same time.

Jesus' actions show consistent confident awareness of his singular nature. He is, after all, the Word.

We can describe covenant as having a split applicability in the Land - his usual personalization of the necessity of Logos and his externalization of Logos in the Land for others to personalize the necessity of. When Mhoram or Borillar have faith that Covenant will redeem the Land, they are also personalizing the necessity of Logos within the externalized applicability of the Land in general.

It's easy to see how this could get out of hand if an author isn't careful. The Illearth War managed it by separating Covenant off with a character that disbelieved his Logos status and interacted with him purely on an interpersonal level. This stage of Covenant's journey is purely human - the inverted psyche and emotional constipation that Elena blows open could pertain to any twisted gamma. But The Power that Preserves does get metaphysical and Mhoram has no doubt about what Covenant is.

If we explode the externalized applicability of the Land, we see Covenant and the white gold is applicable to the Logos. Mhoram personalizes the necessity of this on these terms by maintaining faith under incredible duress and maintaining hope to the last.

Watching him come through the most impossible odds in a life full of them is testimony to the necessity of Logos and the power of faith.

Now we can put it all together and get a better look at how it all fits together. The graphic looks complicated, but look closely and you'll see it's just the same personalized and externalized applicability categories we've been working with all along. The difference now is that we aren't oversimplifying how they actually work out. The power of applicability in this story is the way it simultaneously lights up the necessity of Logos from so many angles within such a riviting narrative.

We could branch down off Mhoram, but that isn't necessary, since his applicability is personalized, but entirely in the externalized terms of the Land. And we can see how he can provide a different personalization of the same issues Covenant represents and have faith in Covenant as applicable to the Logos. It's almost as if the applicabilities are carrying out a conversation with each other.

Any possible confusion arising from Covenant's split applicability within the story is neatly avoided by separating him and Mhoram from most of the book. This allows each arc to play out on its own terms while maintaining the integrity of world and story. They briefly encounter each other around a failed summoning, and from then on they are hundreds of miles apart in totally different contexts.

Covenant returns to Mithil Stonedown and the consequences of the last forty-nine years. This continues his personal journey towards redemption and resolve the different issues around him.

Mhoram is beseiged in Revelstone where distance from Covenant brings his faith into clearer focus. He's always been the proxy Christian, but now he isn't able to interact with Covenant directly.

Mhoram initially decides to summon Covenant because the land is on the brink of destruction. A massive army led by another Stone-bearing giant raver is on it's way to Revelstone and there is no capacity to battle it. The idea presumably is to determine if some effect can be made of the white gold. When Covenant declines, only a few minutes pass in his world before he does come, but weeks have passed in the Land. Mhoram is bottled up in Revelstone, but Covenant appears far from Foul's army in Mithil Stonedown. This actually allows him to move freely and assault Foul's Creche unexpectedly.

The split means that readers lose out on what were always the best encounters in the book though Foamfollower takes up the slack on Covenant's end. And the isolation is necessary for Mhoram's faith - and the hope it spawns - to become central. Without Covenant's physical presence, that's all he has.

He becomes aware of Covenant's return to the Land through the krill on the same night the moon rises green. The artifact of the Old Lords shines shite light when the white gold is in the Land. The timing is perfect, as the powers on either side move into place. We needn't belabor the fact that the link between Mhoram's faith and the Logos is a cross...

The krill keeps Mhoram apprised of Covenant's activities up to the final defeat of Foul. and it's the same cruciform weapon that can handle his new, faith-driven might when his old staff shattered.

On separate tracks both characters can be applicable to the real world - all of us - as people, without tripping over the Christ-Christian dynamic of having them together. There are no other characters to dilute their interaction, and this lets each be true to himself.

Separate arcs also ties up the exploration of the Socio-Sexual Hierarchy. These aren't exactly SSH posts, but the uncanny accuracy and predictive value means it's always in the background.

Edmund Leighton, detail of My Next-Door Neighbour, 1894, oil on canvas, private

We started by noting Covenant's basically gamma nature - he shows us that simpin' really ain't easy. But in The Power that Preserves he resolves his paradoxes, stops lying, faces reality, and goes through hell to deliver a world he still doesn't fully believe in but can't deny.

The nature of the applicability is that it doesn't show what to do - it shows the problem and points to the solution. Logos.

Mhoram faces alpha problems - how to inspire those who lack his boundless faith and use those without his indomitable will. As well as the real danger lurking through the books - how to lead to victory and avoid taking on too much and falling into despair. Ironically, it's Covenant who nearly falls into this one when he decides that the purity of his own hate is sufficient to overcome Foul.

Triock said, “We have sworn the Oath of Peace. Do not ask us to feed your hate. The Land will not be served by such passions.”

“It’s all I’ve got!” Covenant answered thickly. “Don’t you understand? I don’t have anything else. Nothing! All by itself, it has got to be enough.”

Gravely almost sorrowfully, Triock said, “Such a foe cannot be fought with hate. I know. I have felt it in my heart.”

“Hellfire, Triock! Don’t preach at me. I’m sick to death of being victimized. I’m sick of walking meekly or at least quietly and just putting my head on the block. I am going to fight this.”

First - note the difference in Covenant's tone. He's seen what Foul is doing to the Land and the creatures in it. He's faced the madness of Lena - the ongoing consequence of his own original sin in the Land. This on top of his devestated condition when he arrived and acceptance of his own guilt. Without any further plan, he's resolved to take Foul out.

He wouldn't be the first.

yidanyuan, Fingolfin / Of the Battle of Sudden Flame

The whole message of The Illearth War could be called the lesson of The Silmarillion. The ontological impossibility of finite, temporal creatures defeating true immortal evil. Especually in a Fallen material world that the immortal evil marred.

Triock delivers another flush roundhouse...

“Why?” Triock asked in a restrained voice. “What will you fight for?”

“Are you deaf as well as blind?” Covenant wrapped his arms around his chest to steady himself. “I hate Foul. I’ve had all I can stand of—”

“No. I am neither deaf nor blind. I see and hear that you intend to fight. What will you fight for? There is matter enough to occupy your hate in your own world. You are in the Land now. What will you fight for?”

Here's the point where he is hovering over Troy-Elena land. It's a different motivation, but the same overestimation of human capicity. Of mistaking the very great for the truly limitless.

As he spoke, he believed himself. Hatred would be enough. Foul could not take it from him, could not quench it or deflect its aim. He, Thomas Covenant, was a leper; he alone in all the Land had the moral experience or training for this task. Facing between Foamfollower and Triock, addressing them both, he said, “You can either help me or not.”

Oh special, special boy. You alone...

A few other things to hit from earlier. We made the comparison with Greek drama for the clarity of plot and cathartic endings. This is clearest in The Power that Preserves where the character arcs have been reduced to two. The stripped-down narrative and near-perfect structure are among the main reasons why we hold this particular book in such esteem.

Medea in Chariot, Red-Figure Calyx-Krater, around 400 BC

Unique vase with scene from Euripides' Medea of 431 BC, where the sorceress flees after murdering her and Jason's children.

It's not the concision of tragedy in The Power that Preserves but the tight focus on stripped-down character arcs and the intense cathartic endings. The endings aren't tragic either. It's really more the emotional force than anything.

Since we started with the logos structure and the applicabilities, we can now move into Covenant and Mhoram's arcs to wrap up the themes. That's the best way to go, since it follows the structure of the story. But before we, we need to address the initial summoning, since that's the only time Covenant and Mhoram are together. Not counting Covenant's vision at the end, because Mhoram can't see him.

Michael Errigo, A Doorway to Another Dimension, digital art

The metaphysics behind transition to the Land are not explained. Nor is the relationship of the Land to our world.

Covenant is "between worlds" when talking to the Creator but we aren't given any sense of "place". And when the Creator heals him in our world, there is no visible mechanism - the doctors and instruments just register it as a miracle. The two are linked in important ways - it just isn't clear how.

It has been established that there is a connection between the nature of summons, summoner, and the outcome if the summoning. Covenant and Troy have made this painfully clear. And The Power that Preserves confirms that the connection is linked to death.

He was full of grief over the strange ease with which he had summoned the Unbeliever. Without the Staff of Law, he should not have been able to call Covenant alone; yet he had succeeded. He knew why. Covenant had been so vulnerable to the summons because he was dying.

The Land isn't the afterlife but mortality is related to the crossing. The summons is reversed when the summoner dies - unless the person has died in our world like Troy. It is interesting that his summoner died in his stead. And both Covenant and Troy are brought over by what should be insufficient summonings when near their own deaths. And one assumes that when the Creator offers to let Covenant live out his life in the Land that his body in his world would succumb to its injuries and pass away.

John Martin, The Plains of Heaven, 1851–3, oil on canvas, Tate

If summons are existentially important, it matters that the ones here are different from the rest. Mhoram takes the decision to summon Covenant out of desperation, Covenant declines, and Mhoram accepts, letting him go. Despite his knowledge that the ease of summoning combined with Covenants ghastly appearance means he's near death. This is critically important. Despite a clearer understanding of the peril than anyone,

Mhoram stays in the realm of free choice.

He chooses to call Covenant and when rebuffed, respects that choice too. The situation seems doomed, but his hands stay clean and his motives pure. Now his faith will be put to the test.

Gustave Doré, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1855, engraving

Mhoram grapples with his faith in the face of a inexorable sadistic enemy who even bends the weather to his sick will. Faith - hope - Logos is the only path to victory in a fallen world and we can't do it alone. Mhoram understands that external help is needed and because of this he always stays in his lane. The Elena-Troy path isn't for him.

The path of faith is clear. I must follow it—because it is not despair.”

“You will teach us despair—if you fail.”

“No. Lord Foul teaches despair. It is an easier lesson than courage.”

For his part, Covenant declines the summons to save the life of a child, and after he does, accepts the call. The fact that different time rates mean the summons he accepts isn't Mhoram's. But that isn't the point. The point is that he meets one moral imperative first, then opts freely to return to the Land.

Covenant stays in the realm of free choice.

His hands stay clean and his motives pure. Now we will see if he can find a path to faith.

So, two narratives that touch briefly then run to their cathartic conclusions - two arcs that each illuminate each other.

Edwin Deakin, She Will Come Tomorrow, 1888, oil on canvas, Crocker Art Museum

On his end, Covenant is facing a mortal crisis of his own - just personalized. The end of the Illearth War made the disjunction at the end of Lord Foul's Bane seem trivial. The death of Elena, his complicity, then too-late repentance has left him shattered. He can't believe, he can't deny, and he can't escape.

His world has split into irresolvable paradox and the emotional impact smashes through his gamma walls. The little insect-like, mechanistic, soulless mechanisms are woefully insufficient. This is actually a dangerous time in a spiritual progress - the comforting old lies are stripped away but Logos can't be seen yet.

Consider - he refers to his ineffectual life as the "Law" of Leprosy. And we know that on the personal applicability level, leprosy is the active evil - comparable to Lord Foul externalized in the Land or Satan hidden behind the surface of our world. In a fallen world, active evil optimizes passive evil - it's why we are lost here on our own.

Here or there, law cannot check the sympatico alignment of active and passive evil.

The Staff of Law can't answer Foul and the Illearth Stone in the Land.

The Law of Leprosy can't answer wasting disease and spiritual emptiness in Covenant

The Law of the Old Covenant can't answer Satan and fallen human nature in our world.

Evil, pain, corruption, and death of a fallen world smashes through the rice paper defense of Covenant's detached unbelief, reveals his Law as the joke it is, and speeds him towards despair and empty death.

It's notable that he turns to a revivalist preacher - probably an attempt to take a swipe at Christianity, but it reads way differently in 2021. In the 70s, it was easier to believe that frauds in pulpits organized religion was Christianity. Now that we've seen the corruption, inversion, and open satanic wickedness of putative "churches" the piece reads as an excellent indictment of churchianity. That is the worship of "church" as an entity independent of alignment with Christian scripture. Or tradition.

Mainstream Catholicism and Protestantism have replaced Christianity with a bizarre godless structure based on human whims, rejecting God's stated commandments and beatitudes, and wallowing in self-righteousness and self-indulgence.

The problem isn't "prosperity gospel". It's the whole corrupt structure that turns churches tax haven adjuncts of Mammon and Caesar.

Now set aside the grasping whores in obscene megachurches who profane His name and look at what the real Christ actually said. That is, the guy whose title is the root of the "Christianity" that the whores treat as a brothel.

Consider the woes from the Sermon on the Plain. While it is true that Jesus' words have deeper meaning than the literal, it is still impossible to reconcile this with the fake churchianity practiced today.

We realize that this doesn't sit well with the mindless, spiritually-dead chuds filing the pews of these inverted temples. Which is fine - salvation remains a choice.

A litmus test? Ask if your "faith leader" pushes interpretations of scripture where allegory or symbolism contradicts the surface meaning. Not adds to, enriches, applies, or clarifies, but claims incompatible or inverted meaning or makes fundamental changes. The answer is is whether you're Christian or churchian. It is up to you, but there are eternal consequences and it's best to decide with the final outcome in mind.

Of course the whole point of churchianity is to falsely claim the spiritual comforts of salvation while ignoring the stated terms and conditions. Opting for a smooth liar whose words bring more material ease than that demanding Jesus who they falsely claim to follow.

Of course Jesus himself spells out the consequences of disobeying his message and choosing a life of material reward and pleasure over the spirit. He then leaves the rest up to you.

Jesus warns us that it's a narrow gate - that our appetites and desire for the easy path make the road to salvation difficult, even with his sacrifice opening the way. Churchian frauds declare their blasphemous nature by assuring the slop-wallowers that everyone's in. That is, directly contradicting the Savior's words. They are a spiritual corruption that plays on our fallen natures to ensure the ultimate destruction of our souls. A globalist politician is infinitely less evil.

As we said, it's a free choice.

To the surprise of no one, the fake priest is unable to do a thing for Covenant - physically or spiritually. Unable to go on and with nothing to live for, Covenant neglects his frail health until he's on death's door. When he makes a stand and performs one selfless act.

Johannes Vermeer, Allegory of the Catholic Faith, 1670–72, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

That he rescues a little girl from a snake seems appropriate. Defeating the serpent is an old Christian symbol for the triumph over evil brought by the Incarnation. The iconography is Catholic here, but the idea of the rock of the church crushing evil isn't hard to adapt to a general Christian context.

The transition from his obsessive self-centeredness at the beginning to total self-sacrifice now is clear progress along his logos journey.

Clear progress, it also shows the dangers. Covenant has realized the inadequacy of his old way but not how to proceed. He doesn't know how to live. Despair isn't "feeling sad", although that can be a big part of it. It's giving up. Covenant's rescue isn't suicidal if he hadn't abandoned himself to pain and grief.

It's a slow suicide, but a suicide all the same. Self-destruction allows disillusionment with a fake reality to blind oneself to their place in Creation. At this point, the Logos journey has failed - he has become open to larger realities, but the result is self-immolation rather than growth into new truth. But by finally looking beyond himself, he has opened a breech in his shell that makes it at least possible for new truth to enter.

It's like a dark night of the soul - existential bleakness. But it's the element of self-sacrifice that breaks the shell and shines a ray of morality into the darkness.

The Land people other than Mhoram criticize the refusal of the summons to save a girl to be immoral - one life against a world. Of course, they have a different perspective on the value of their existence. But from the perspective of the personalized applicability of Covenant's Logos journey, he took responsibility for himself, identified a selfless moral priority, then gave everything he had to do it. In his confrontation with Mhoram he articulates this, speaks truthfully about his plans, takes his own stand, and holds to it despite outside pressure.

We can argue the rightness of his choice. What we can't argue is that he is engaging with reality as a self-driven moral agent and not hiding in a fake bubble like a gamma ant.

We don't want to push the Christ-figure parallel because it doesn't really hold up. Applicability stops us from over-determining it. But Covenant basically sacrifices his own life to save another - we later find out that without the Creator healing him at the end, he would have died. And that's not an outcome he could have planned on. But it is interesting from a logos perspective that he rejects false priests and engages in a sort of saving self-sacrifice before rising again to redeem a world.

It's like there's an applicable pattern...

One selfless act leads to another...

"All right, Mhoram,” he mumbled wanly. “Come and get me. It’s over now.”He did not know whether he had spoken aloud. He could not hear himself. The ground under him had begun to ripple. Waves rolled through the hillside, tossing the small raft of hard soil on which he sat. He clung to it as long as he could, but the earthen seas were too rough. Soon he lost his balance and tumbled backward into the ground as if it were an undug grave.

...and Covenant returns to a Land on the brink.

We've seen how his gamma nature was already disjointed from reality - his leprosy pushes him further from logos. Into something resembling a situational omega. But the savage firehose of emotional reality breaks through and he does the opposite. He chooses charity over self and then service.

Neither are gamma traits. What will he become?

DarthIggy, Kevin's Watch

Covenant's arc picks up on Kevin's Watch outside of Mithil Stonedown - where his story began. He's given the opportunity to revisit the site of his original sin in the Land, to see the consequences, and to make better choices. It's a lot harder this time because of the damage caused by his past crimes and errors.

After his recent exertions, he was too weak for such labor. But he felt cold, upright, and passionate, ballasted by the new granite of his purpose. He went with Lena, Slen, and the Circle of elders to the banks of the river, and there helped treat the injuries of the Stonedownors...

All the while, a deep rage mounted within him, grew up his soul like slow vines reaching toward savagery.

This is another sign of that tremendous structuring. First - the visceral display of the necessity of logos on a personal level. Then, common morality between Covenant and Mhoram is established before deftly splitting their arcs. Now an old circle will close as The Sins of the Father come home to roost. Covenant must face, come to grips with, and resolve his sins, while those harmed by him face similar quandaries.

The Land Covenant returns to is in the final year of Foul's prophecy and ravaged by an unnatural winter. The full consequences of Elena's monstrous sins come into focus - breaking the Law of Death gave Foul additional powers, including indirect control of the Staff of Law itself.

The green moon is the most obvious sign of the corruptibility of Law before the union of passive and immortal active evils in a fallen world.

Revelwood has been burned and Revelstone is besieged by an army comparable to the one in the Illearth War. The rest of the Land faces uncertain exile or extermination by an artificial winter and bands of ravening creatures. Even the healing hurtloam had retreated. The Land is dying.

Covenant lets go and accepts his summons, but doesn't return to Mhoram. He answers a different call - one that gives them independent story arcs and brings Covenant back to the beginning. His summoners make this closing the circle dimension obvious. It's Triock and Saltheart Foamfollower using the High Wood that Mhoram predicted Triock would have need for in The Illearth War.

Several applicabilities come in here.

The Sins of the Father.

We've already seen the wreckage of Elena, Trell and Atairan. The "simple cowherd" Triock never was the one who never stopped loving Lena, raised Elena as best he could, and after the Illearth War studied lore and became a fierce guerilla fighter for the Land. Scarred by bitterness and unable to truly forgive Covenant, he does the right thing through force of character. And though his life of pain ends in violence, he proves sufficient in the end.

Again Triock looked at Covenant’s injuries. “Yes,” he sighed wearily. “Pardon me, Unbeliever. I have spent seven and forty years with people who cannot forget you. Be at rest—we will preserve you from harm as best we may. And we will answer your questions.

Triock is applicable as the bleak struggle of morality without logos in a fallen world. Stoicism would be the closest counterpart. What we know is that the Prince of this World is materially invincible, the world is entropic and everything dies. You can fight it on your own, but the path will be full of suffering and error, and possibly the affront to God's Creation called suicide.

Manuel Domínguez Sánchez, The Death of Seneca, 1871, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado

Consider - playing the 'whose pain is worse game' is sociopathic, but it is fair to say that the total amount of carnage Mhoram has witnessed - including burying his parents after a fiery massacre, locking wills with a raver, and communing directly with Lord Foul in dreams - is at least comparably traumatic to Triock's life. But Mhoram remains kind, humble, forgiving, humane. That's the difference between moral life in a fallen world with or without faith in Logos.

We have the Logos for a reason. Ultimate reality trumps the abstract just as the abstract trumps the material.

We also learn Lena never recovered.

Circle Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A study of the head of an old woman, 18th century, black and red chalk on buff paper, private

Her mind was broken after rape by a god, a parade of magic horses, the god's prodigy child, all of it - she exists in a timeless delusional state where she awaits his return.

“Do you not know me, Thomas Covenant?” she said gently. “I have not changed. They all wish me to change—Triock and Trell my father and the Circle of elders, all wish me to change. But I do not. Do I appear changed?”

“No,” Covenant panted...

She smiled with relief. “I am glad. I have striven to hold true. The Unbeliever deserves no less.”

Her story is just heartbreaking. The poignance when he tells her he will have to leave again. Her anguish at the news of Elena. Her brutal graveless death. And the tragedy of holding true to the end. This really sucks.

With an effort, she opened her eyes. They were clear, as if she were finally free of the confusion which had shaped her life. After a moment, she recognized Covenant, and tried to smile.

“Lena,” he panted. “Lena.”

“I love you,” she replied in a voice wet with blood. “I have not changed.”

“Lena.” He struggled to return her smile, but the attempt convulsed his face as if he were about to shriek.

Her hand reached toward him, touched his forehead as if to smooth away his scowl. “Free the Ranyhyn,” she whispered.The plea took her last strength. She died with blood streaming between her lips.

Sins of the Father indeed.

The applicability to immorality is obvious. It is also worth nothing how Lena's deluded faith made her the only character not consumed with bitterness. But her faith is misguided by confusing the personal - Covenant - with the applicable - the Logos. This stems from the larger confusion of Covenant operating on multiple levels in the Land - the same issue that separation from Mhoram avoids.

Faith alone isn't enough. It has to be faith in the right thing. Epistemologically, faith is just a form of knowledge, and can be as wrong as any other. It's not a magic bullet in itself - that's secular transcendence.

Foamfollower is in a different place. His crisis is not the fault of Covenant, so their relationship is different. He returned home after Lord Foul's Bane but rejected the despair and death of his people and fled rather then fight the giant-raver executioner. Plagued by guilt and anguish, he becomes a wandering fighter against Foul's creatures and eventually falls in with Triock and his group. He also falls in love with killing and is facing an existential crisis of his own.

The applicability of Foamfollower is the danger of becoming what you hate.

When we met him, he was the soul of creativity spirit. The giants in general burst with exuberance and overall virtue. But bathing in the blood of his enemies has left him a fierce killer, but no longer able to laugh. Nor can he seek release in his camora ritual. He's lost his own tie to logos and become as grimly purposeful as Triock.

How does Covenant respond? He is repeatedly rocked with grief, horror, and guilt.

Rapidly he whispered, “Atiaran’s judgment is coming true. The Land is being destroyed, and it’s my fault.

And later...

Covenant stared at it as if it were vituperation. His eyes had a feverish cast, a look of having been blistered from within. No words came to his mind, but he knew what had happened. Rape, treachery, now murder—he had done them all, he had committed every crime.

He helps, selflessly to the limits of his strength, and rescues Lena from certain death. Afterwards, he is honest that he doesn't know what to do, then fully discloses his intentions when they've formed. He's decided to finally fight, and while his motives are off, there is something bracing about the line "I'm going to bring Foul's Creche down around his ears".

The applicability of Covenant here takes us a step further down the logos path from his suicidal opening. His ring healed himself sufficiently to be out of immediate danger and he's found some direction. It's a very common one in people awakening from beast system sleep - acceptance of the reality of evil and and the anger and revulsion that come with it.

As always, making due with pictures we can find - like fantasy art on an on-line D&D campign. Click for source. But it captures the reaction many have when they become aware of the reality of evil for the first time. Real evil, not the maladjustment, moral relativist nonsense peddled by the soul-dead for their own short-term gain.

Covenant can't deny the weight of horrors piled up by Foul. Whether he can use or even really believes in his ring is irrelevant. He's seen all he can take, and he is consumed with hatred. Hatred and the burning desire to crush Foul out of existence.

He very nearly falls into Troy's trap - believing human extremity can match immortal evil.

“I am going to”—Covenant’s shoulders hunched—“exterminate Lord Foul the bloody Despiser. Isn’t that enough for you?”“Oh, it is enough for me,” Foamfollower said with sudden vehemence. “I require nothing more. But it does not suffice for you. What do you believe—what is your faith?”“I don’t know.”Foamfollower looked away again at the weather. His heavy brows hid his eyes, but his smile seemed sad, almost hopeless. “Therefore I am afraid.”Covenant nodded grimly, as if in agreement.Nevertheless, if Lord Foul had appeared before him at that moment, he, Thomas Covenant, Unbeliever and leper, would have tried to tear the Despiser’s heart out with his bare hands.

But the picture misleads. The righteous being attacking the demon here is another immortal while Covenant is a man. More death, tragedy, suffering, madness, and an unexpected forest healing teach him his limits. The new plan is to avoid Foul altogether. If this is a dream, the only way Foul wins is to kill him. Flee into the wider world, Foul never finds him, and his ultimate victory is deferred forever.

This obviously can't work - Foul literally has forever to find the white gold. But look past the plausibility to the intent. Like his final pleas to Elena, there is a willingness to abandon himself to the Land for a greater good.

Johari Smith, Magical Forest Path, 2016, digital art

Short term, he's right. Foul does need the ring. Killing the Land is a pleasant diversion, but it won't get him out of the arch of time. And trying to track Covenant through the uncharted paths of the world beyond is not part of any plan.

Once Covenant leaves the healing shelter of Morinmoss Forest, he is waylaid by a raver and brought to what looks to be a final showdown. Running away isn't an option either.

The showdown with two ravers, Triock, and the Stone-possessed shade of Elena reveals the source of Foul's enhanced power over the world. Two things happen - Triock redeems himself and buys Covenant the opening to regain his ring. And Covenant vaporizes the Staff of Law with such ease that the whole sense of power in the story shifts. The shades are released and Foul's hold on the natural world abruptly ends.

Darrell Sweet, The Power that Preserves cover art

Sweet was a prominent professional fantasy artist who was more competent than inspired. The basic parts of the confrontation are here - a moment before Covenant shreds the Staff.

Earlier posts noted what looks like a topological relationship in The Chronicles that is applicable to the Old and New Testaments of the Bible. Moses foreshadows Christ and Logos replaces and fulfills Law. Berek fashions the Staff of Law and founds the Old Lords -very much an Old Covenant by the time we get to the story. One that fails.

White gold destroys the Staff of Law, ending what had become a corrupt inversion of its original intent. Berek foreshadows Covenant and Logos replaces and fulfills Law.

He is even named Covenant...

Without getting too theological, Covenant's madness, near death experience, consideration of running away, and briefly losing the ring are applicable to a sort of Passion. Not directly - that would bring us into allegory and The Chronicles aren't that. But it isn't hard to see a similar path of psychic and physical anguish leading to rebirth and salvation. He does basically sacrifice his inclinations and arise again with... well... the power that preserves.

Succinct Christian covenant diagram scraped from the internet that captures the failure of the Old and the completely different configuration of the New.

Covenant replaces the Law, is figuratively reborn, and delivers the Land.

It certainly looks like this to Mhoram...

Lord Mhoram - the personal applicability of the necessity of Logos externalised.

Mhoram's arc after the failed summoning is very different. He is trapped in Revelstone and facing the end of all he's worked for. The scenario is dire - the walls can resist the enemy but the people are trapped and increasingly desperate. The fortress site was chosen for a large fertile upland plateau only accessible through Revelstone itself. Enough crop and pastureland to sustain the city indefinitely. But Foul's winter means no new food for the stores. And no way to replace fallen defenders.

The enemy is Satansfist - last of the giant-ravers and commander of an army comparable to the one in The Illearth War. We are told that the first army was only a third of Foul's forces, so even an improbable victory is pyrrhic at best. Not that that is likely - the imbalance is far worse than before and both the Bloodguard and Troy's tactical genius are lost.

In SSH terms, Mhoram is an alpha. A natural leader whose instincts tend to be right and who people are drawn to follow. This sets him up for dispair and ruin in several ways. The big one is Kevin's hopelessness.

That's when the great leader exhausts all their immense gifts for naught and stands helplessly before the final destruction of all they've worked for. Realizing their fundamental inadequacy - perhaps for the first time - when adequacy was most desperately needed.

Without Thomas Covenant—! Mhoram could not complete the thought… This, he told himself, was what Kevin Landwaster must have felt when Lord Foul overwhelmed Kurash Plenethor, making all responses short of Desecration futile. He did not know how the pain of it could be endured.

Mhoram's answer is his faith. At no point does he claim ultimate responsibility for the survival of the Land. It's clear through the trilogy that he believes the final salvation of the Land rests in Covenant's hands. And Covenant is the direct instrument of the Creator - with as close to God's power as the world can contain. The challenge for him isn't if he can save the Land. It's if Covenant will.

William Blake, Job Rebuked by His Friends, from the Book of Job, pen and black ink, gray wash, and watercolor, over graphite, 1805

The question is one every Christian has to resolve

Is my faith misgiven?

Then there are the problems of leadership. The people lack Mhoram's faith, insight, virtue, and strength of character. If he is facing the strain, how are they doing? As an alpha, he takes their hopes onto himself, but he can't promise victory. That's Troy's fall.

“Ah, my Lord. Then why do you delay? Why do you fear?”

“Because I am mortal, weak. The way is only clear—not sure. In my time, I have been a seer and oracle. Now I—I desire a sign. I require to see.”

But faith in him also has to be misguided. He is a man. It's the same error of mistaking the materially exceptional for the absolute. Mhoram repeatedly pulls rabbits out of hats, to the point where people who know him see him as something of a miracle worker. He isn't - he's just extraordinarily blessed with positive qualities and unshakable properly-guided faith. So there are no guarantees he keeps winning. And if he goes down, the hopes of all those weaker souls go down with him.

He needs to learn how to trust those less capable and get the most out of them. It's a problem for any gifted individual in a leadership role. It's easier and gives better results to do things yourself. Trying to push forward and drag the reticent at the same time can feel like fighting on two fronts.

And sometimes you get it wrong - Mhoram hoped gentleness could make room for Trell to heal.

But when he does make a mistake he recovers quickly and learns. And his mistakes are morally well-intended - over-estimating others rather than himself. In the case of Trell, we are privy to Mhoram's inner monologue. It was a reasoned decision, based on sound ethics, that went wrong in the Valley of Shadow. Very different from doing what he wilt and expecting reality to bend.

The fact that Revelstone resists as long and effectively as it does is testimony to Mhoram's alpha leadership. But this positions him over the Kevin trap as he is increasingly aware of the inevitability of their destruction no matter what he does.

There's a scene where Mhoram journeys to the upland lake Glimmermere alone and bathes in the frozen air. There, he finds the brutally simple solution to their immediate problem...

He had to do something which was obviously impossible. He had to slay samadhi Satansfist.

Then he does.

Put aside everything we've seen of the absurd power levels of the giant ravers, the vastness of the army, the support of Foul's vast might... it is the only logical resolution to the current crisis. But given all that, only an alpha would come up with that as the action plan. What makes him a hero is that he pulls it off.

Contrast his thought processes to Elena or Troy.

Donaldson doesn't have the same grasp of alpha subtleties as he does gamma, but his verisimilitude gets some big ones right.

Mhoram is wracked with questions, doubts, second and third guesses while planning, and unsure of the final direction. But once he's figured out a course of action, he acts with laser focus and without hesitation. In other words he is cautious and analytical when that is needed and single-minded and determined likewise.

There are no grand proclamations of intent, promises of victory, or shouldering of impossible collective burdens. He accepts the inescapable logic of the situation - either Satansfist dies or Revelstone falls. But his decision binds only himself. If he fails, Revelstone falls, but Revelstone is falling anyhow. There is no additional cost - only possible upside.

“This choice is mine. I will ride against Satansfist alone if I must. But this act must be made.”

As impossible as it seems, there is a logic here. The logic of the brave over the tendency to gravitate towards momentary safety regardless of cost. Attacking injects a mote of uncertainty into what is otherwise necessary defeat. Only a little, but that's infinitely better than no chance at all. And Mhoram is an absolute master of capitalizing on one tiny opening and parlaying it into impossible outcomes. The logic - to save Revelstone, Satansfist has to die. Mhoram is the only one who could even conceive of doing it, so he has to be the one to go. And given his personality, what tiny odds he has are maximized if he can throw some chaos into the field. If there is a way to win, that's when his particular talents will best be able to find it.

The logic is crystaline. The courage is the question. That and actually spinning the tiny bit of chaos into...

Just read the chapter. "Lord Mhoram's Victory".

Discover a way!

Mhoram's shouted command to Troy in The Illearth Waris nothing he fails to uphold himself to. Trapped in Revelstone, the fate of the Land is assured. But set things in some unexpected motion?

If there is a way, this is when he will discover it.

Mhoram's strength and humility come from the same place - his unshakable faith. We've seen his belief in the benevolence of the Creator and certainty that the fate of the Land is in Covenant's hands. When Covenant does return to the Land, his newly activated moral compass is stinging from having rejected Mhoram. His attempt to have word sent to Revelstone fails, but it turns out Mhoram knew anyhow.

The cross told him.

The table was intact. In its center, the gem of the krill blazed with a pure white fire, as radiant as hope.

Mhoram heard someone say, “Ur-Lord Covenant has returned to the Land.” But he could no longer tell what was happening around him. His tears seemed to blind all his senses.

Following the light of the gem, he reached out his hand and clasped the krill’s haft. In its intense heat, he felt the truth of what he had heard. The Unbeliever had returned.

With his new might, he gripped the krill and pulled it easily from the stone. Its edges were so sharp that when he held the knife in his hand he could see their keenness. His power protected him from the heat.

He turned to his companions with a smile that felt like a ray of sunshine on his face.

“Summon Lord Trevor,” he said gladly. “I have—a knowledge of power that I wish to share with you.”

Actually the krill - another one-syllable word starting with a hard c. An ancient eldrich cruciform dagger that lights up when the white gold is in the Land. So pardon us. When the krill radiates a pure white light, Mhoram knows Covenant has returned.

The test of his faith comes when Covenant falls into the hands of the raver and the shade of Elena takes the ring. The green light in the krill is like a death knell. But even then Mhoram refuses to despair and remains within himself. Certain that Satansfist has to be killed, he leads a desperate attack, is cut off from his forces, and puts up the absolute fight of a life filled with them. His final answer to despair?

Bring it with everything he's got.

As he grasped the utterness of his plight, he turned inward, retreated into himself as if he were fleeing. There he looked the end of all his hopes and all his Landservice in the face, and found that its scarred, terrible visage no longer appalled him. He was a fighter, a man born to fight for the Land. As long as something for which he could fight remained, he was impervious to terror. And something did remain; while he lived, at least one flame of love for the Land still burned. He could fight for that.

Turns out his everything is quite a bit.

During his reflections, Mhoram realized that the same Oath of Peace that protects them from Kevin's despair is what keeps them from the Old Lord's power and lore. That the zenith comes with the nadir - That flight risks crashing. That the risk of Desecration is intrinsic to the power.

Willem Vrelant, Adam and Eve Eating the Forbidden Fruit, early 1460s, tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, Ms. Ludwig IX 8 (83.ML.104), fol. 137, Getty Museum

Applicability - There are no shortcut certainties - no handy failsafe laws - to replace moral reasoning in a fallen world.

Knowledge of good and evil comes with personal responsibility for outcomes. And each individual has to face the same tests. This was the part the serpent left out.

In effect, the Oath of Peace is applicable to mouse utopia-type attempts at building a material paradise in a fallen world through human means. The compulsive rush from fake system to fake system to escape personal responsibility for outcomes is like a mental illness. Variations of "if some of us fluff this piece of paper while pretending everyone is, bad things can never befall us".

But consider what the Fall brought - knowledge of good and evil. Immorality is baked into our epistemological formation. The Incarnation didn't reboot the world to prelapsarian laws of nature. It gave us the capacity to make moral judgements in full knowledge of good and evil. It didn't absolve responsibility, it gave us the choice to be responsible.

There is no systemic escape from personal moral

accountability in a Fallen world

Mhoram's realization allows him to access power that had been lost since the fall of Kevin. An that opens the possibility for another Ritual of Desecration of Kevin's magnitude. That becomes his moral responsibility. But it also levels him up into what is essentially an Old Lord. And an Old Lord with Mhoram's will turns out to be a buzz saw.

Cut off and facing waves of Foul's creatures, we see first hand why Mhoram is so capable. He never stops coming. He's always moving, always probing, and constantly on the attack. A small mobile target spewing enormous amounts of power keeps his enemies from surrounding him and bringing him down for good.

He was only one man against several hundred of the black, roynish creatures. But he had unlocked the secret of High Lord Kevin’s Lore; he had learned the link between power and passion; he was mightier than he had ever been before. Using all the force his staff could bear, he shattered the formation like a battering ram, broke and scattered ur-viles like rubble. With Drinny pounding, kicking, slashing under him, he held his staff in both hands, whirled it about him, sent vivid blasts blaring like the blue fury of the cloud-damned heavens, shouting in a rapture of rage like an earthquake. And the ur-viles staggered as if the sky had fallen on them, collapsed as if the ground had bucked under their feet. He fired his way through them like a titan, and did not stop until he had reached the bottom of a low hollow in the hills.

But before any of the eldritch knives could bite his flesh, he mustered an eruption of force which blasted the ur-viles away. Instantly he was on his feet again, wielding his staff, crushing every creature that came near him—searching fervidly for his mount.

Remember why he's out here. Satansfist has to be killed, and the only chance - no matter how remote - was to go on the offensive and insert chaos into an otherwise certain thing. He was unable to engage on the openig sortie and winds up cut off. But he never gives up. He never stops moving and disrupting - continuing to create the chaos where an improbable chance might appear.

His problem becomes practical. His staff was made by the New Lords with their limits and can't handle the amount of raw power he's forcing through it. It's worth the extended quote.

Now the only thing which limited his might was his staff itself. That wood had been shaped by people who had not understood Kevin’s Lore; it was not formed to bear the force he now sent blazing through it. But he had no margin for caution. He made the staff surpass itself, sent it bucking and crackling with power to rage against his assailants. His flame grew incandescent, furnace-hot; in brilliance and coruscation it sliced through his foes like a scythe of sun-fire.In moments, their sheer numbers filled all his horizons, blocked everything but their dark assault out of his awareness. He saw nothing else, felt nothing but huge waves of misshapen fiends that sought to deluge him, knew nothing but their ravening lust for blood and his blue, fiery passion. Though they threw themselves at him in scores and hundreds, he met them, cut them down, blasted them back. Wading through their corpses as if they were the very sea of death, he fought them with fury in his veins, indomitability in his bones, extravagant triumph in his eyes.Through the savage clash of combat, he heard a high, strange cry of victory, but he hardly knew that he had made it himself.

When he finally laces it across Satansfist's head with enough force to send the giant flying, the staff explodes. Stunned, and with no implement to channel his power, Mhoram is about to be struck down by the wounded giant-raver when...

Ron DiCianni, detail from the Resurrection, 2008-2010, oil on canvas, Museum of Biblical Art, Dallas

The white gold disintegrates the Staff of Law, the New Covenant emphatically replaces the Old, even the dead are redeemed, and the cross krill blazes back to life.

But now Mhoram felt the fire which burned against his flesh under his robe. In a rush of exaltation, he understood it, grasped its meaning intuitively. As the Stone reached its height over his head, he tore open his robe and grasped Loric’s krill.

Its gem blazed like a hot white brazier in his hands. It was charged to overflowing with echoes of wild magic; he could feel its keenness as he gripped its hilt.

It was a weapon strong enough to bear any might.

His faith affirmed and rewarded, Mhoram pits his full strength against the giant-raver and his Stone in a horrible stalemate. But he has discovered a way. His injection of chaos was sufficient to get him into a toe-to-toe fight with Satansfist - hardly a dream date, but remember the revelation at Glimmermere. If he was to kill the giant-raver without extravagant promises to the group, he had to arrange for this confrontation. Now he just has to win.

And faith in Logos is a power with which all things are possible.

Even killing a demonic juggernaut with a blazing hallowed cross.

Savage power steamed and pulsed like the beating of a heart of ice—a heart laboring convulsively, pounding and quivering to carry itself through a crisis. Mhoram felt the beats crash against the back of his spine. They kept Satansfist alive while they strove to quench the power which drove the krill.

But Mhoram endured the pain, did not let go; he leaned his weight on the blazing blade, ground it deeper and still deeper toward the essential cords of samadhi’s life. Slowly his flesh seemed to disappear, fade as if he were being translated by passion into a being of pure force, of unfettered spirit and indomitable will. The Stone hammered at his back like a mounting cataclysm, and Satansfist’s chest heaved against his hands in great, ragged, bloody gasps.

Then the cords were cut.

Pounding beyond the limits of control, the Illearth Stone exploded, annihilated itself with an eruption that hurled Mhoram and Satansfist tumbling inextricably together from the knoll. The blast shook the ground, tore a hole in the silence over the battle. One slow instant of stunned amazement gripped the air, then vanished in the dismayed shrieks of the Despiser’s army.

Foul's massive feral army eventually does what you would expect when the overwhelming magic force that held it together is suddenly lifted. There's no need to describe that many savage bestial creatures with no food, no where to go, no leadership, and no compulsion. Suffice it to say the siege takes care of itself, though the clean-up will take some time.

That Mhoram survives drives home the applicability of the essential nature of faith and Logos in this fallen world.

Mhoram’s robe draped his bloodied and begrimed form in tatters; it had been shredded by the explosion. His hands as they gripped the krill were burned so badly that only black rags of flesh still clung to his bones. From head to foot, his body had the look of pain and brokenness. But he was still alive, still breathing faintly, fragilely.

We did say he brought it with everything. Applicability - he held true to his faith, never gave up, never stopped stiving to turn an impossible situation, and had his faith affirmed in the most rewarding possible way.

After the defeat of the Ravers and Elena, Covenant and Foamfollower resolve to go to Foul's Creche. Bannor goes his own way - leaving us to contemplate another instance of the danger that comes from mistaking the excellent for the truly eternal.

The Bloodguard are another memorable creation - tireless, sleepless, undying bare-hand fighters that defend the Lords. Until their Vow of pure service is twisted and corrupted by the Illearth Stone. We'd like to have given them more atention but the posts can only cover so much.

Wan Young Yun, Figure

A last reminder of the difference between the temporal and material and the truly immortal. The patent absurdity of secular transcendence is a major theme here.

No.” Bannor denied the charge flatly. “What help I can, I will give. But Ridjeck Thome, Corruption’s seat—there I will not go. The deepest wish of the Bloodguard was to fight the Despiser in his home, pure service against Corruption. This desire misled. I have put aside such things.

Bannor cocked a white eyebrow at the question, as if it came close to the truth. “I am not shamed,” he said distinctly. “But I am saddened that so many centuries were required to teach us the limits of our worth. We went too far, in pride and folly. Mortal men should not give up wives and sleep and death for any service—lest the face of failure become too abhorrent to be endured.”

A series of adventures follow that we don't need to retrace. The main value is to provide an opportunity for Covenant and Foamfollower to build their relationship through a series of excellent conversations. Covenant figures out the answers to his dilemma. Meanwhile, Foamfollower is lost in his own way, having given himself over to bloodlust as a tonic for his pain. But like any drug, the fix is temporary, and the cost is his soul. Remember creativity is applicable to externalized Logos - Covenant abandoning his writing was a huge sign of his fall into darkness. Foamfollower has also lost his gifts of storytelling and mirth.

An interpretation of Foul's promontory lair that we mentioned at the start of this post. The perfect emerald halls are in the interior - the outside is not so nice.

Crossing the river of lava brings Foamfollower to his own apotheosis and purification. He will play an important role in the destruction of Foul by recovering his laughter. Logos.

It should be noted that the long hungry trek through the wasteland is kept to a minimum. This is an unfortunate trope in fantasy books - we blame the journey through Mordor for this bit of tedium. Here, it is not too lengthy and serves as an extended platform for the conversations that lead Covenant and Foamfollower to the necessity of Logos. And any "oh Sams" are notably absent.

The fight between Covenant and Foul lives up to the billing. In a nice bit of closure, Covenant - who still can't call up the power of the ring on his own - is able to get close enough to trigger it with the Illearth Stone by seeming weak and beaten. Foul's one worry from the start of the trilogy - the one reason he didn't just take the ring - was that he feared Covenant was playing possum to lure him into a one-on-one fight. The one scenario he can't game to his favor.

Which is exactly what Covenant does.

In the apocalyptic clash that follows we learn how powerful immortal evil in a fallen world really is. The energies wielded by Foul and the Stone far exceed anything we've seen to this point. You realize in an instant how hopeless material beings are before him.

Even Mhoram couldn't find a way here.

Then we learn how powerful the Logos is.

Again Lord Foul struck. Power that fried the air between them sprang at Covenant, strove to interrupt the white, windless gale of the ring. Their conflict coruscated through the thronehall like a mad gibberish of lightning, green and white blasting, battering, devouring each other like all the storms of the world gone insane...The savagery of the Stone made a holocaust around him, tore every last flicker of warmth from the air, shot great lurid icicles of hatred at him. But he did not falter. The wild magic was passionate and unfathomable, as high as Time and as deep as Earth—raw power limited only by the limits of his will. And his will was growing, raising its head, blossoming on the rich sap of rage. Moment by moment, he was becoming equal to the Despiser’s attack...Soon he was able to move. He forged away from the wall, waded like a strong man through the tempest toward his enemy. White and green blasts scalded the atmosphere; detonations of savage lightning shattered against each other. Lord Foul’s fiery cold and Covenant’s gale tore at each other’s throats, rent each other, renewed themselves and tore again. In the virulence of the battle, Covenant thought that Ridjeck Thome would surely come crashing down. But the Creche stood; the thronehall stood. Only Covenant and Lord Foul shook in the thunderous silence of the power storm.

We weren't exaggerating when we said they throw down at the end. As Covenant grows more comfortable with his own energies, he can escalate past Foul's ability to match. He pounds him away from the stone, pins him, and slowly strips off his enchanted shell, revealing the godlike form beneath.

By faint degrees, he became material, drifted from corporeal absence to presence. Perfectly molded limbs, as pure as alabaster, grew slowly visible—an old, grand, leonine head, magisterially crowned and bearded with flowing white hair—an enrobed, dignified trunk, broad and solid with strength. Only his eyes showed no change, no stern, impressive surge of incarnation; they lashed constantly at Covenant like fangs wet with venom.

When he was fully present, Lord Foul folded his arms on his chest and said harshly, “Now you do in truth see me, groveler.” His tone gave no hint of fear or surrender. “Do you yet believe that you are my master? Fool! I grew beyond your petty wisdom or belief long before your world’s babyhood. I tell you plainly, groveler—Despite such as mine is the only true fruit of experience and insight.

What's interesting is that he doesn't try a deathblow. He realizes Foul can't be killed that way, any more that the Incarnation undid the Fall. Instead he, a purified Foamfollower, and the redeemed dead Lords laugh Foul into oblivion. It sounds anticlimactic, but it really isn't. The answer was raw power and virtue in equal measure.

Of course there is a little more raw power to take care of the Stone. In terms of applicability, think of the Logos taking a little of the edge off the fallen world, even if it can't be fully restored.

At once, ocean crashed into the gap from the east, and lava poured into it from the west. Their impact obscured in steam and fiery sibilation the seething caldron of Ridjeck Thome’s collapse, the sky-shaking fury of sea and stone and fire-obscured everything except the power which blazed from the core of the destruction.

It was green-white—savage, wild—mounting hugely toward its apocalypse.

But the white dominated and prevailed.

The conclusion clears up a few questions. We finally meet the Creator, whose explanation indicates Mhoram's metaphysics were basically correct. And who offers a reward in gratitude to Covenant for delivering his creation. It's interesting that Covenant declines the cure of his leprosy in his world or a life of ease in a Foul-less Land. He simply opts for a reset - miraculous healing of the snake venom, infections, malnutrition, and the things killing him directly.

In terms of applicability, there is no magic restoration to Eden. Foul/Satan is subdued but not gone - that will require the New Covenant to be upheld. The world still is a pit of snares that takes constant vigilance and moral reasoning. But he has logos now, which is what we really need. The capacity to make moral judgements in full knowledge of good and evil. It didn't absolve responsibility, it gave us the choice to be responsible.

There is no systemic escape from personal moral

accountability in a Fallen world

We've mentioned a few times that the sequels were unwritten. That's because the endings here so perfectly close the Logos journey that continuing the story replaces applicability with the typical godless paganistic shit that never coheres because it's like the photocopy of the photocopy of a lie.

Consider how the arcs wrap at the end of The Power that Preserves.

Alexandre Calame, Der Vierwaldstättersee (Symphony in Blue), 1855, oil on canvas, private

The Creator appears and gives Covenant - and us - a final look at Mhoram and the survivors of Revelstone as spring pushes Foul's winter aside. He leaves knowing his friend made it too.

Mhoram reveals he knew Covenant's story from the echoes of the battle with Foul in the krill. He then throws the krill into Glimmermere and vows to find a new, less dangerous path to service. This can go two ways.