If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.

Continuing the roots of the West and the long journey to modernism in art. Or what we call Art! as a way of distinguishing the inverted modern version from the actual concept. Long is an understatement. The earlier ones live on in the linked page up above. We'll jump right in.

The last post identified the second major step along this path – art becoming theoretically self-conscious as a sphere of activity in the early Renaissance. Click for a link. The first was the emergence of a cultural activity that we as moderns can recognize as “art” in the late Middle Ages. And this brought up more observations about Renaissance history in turn. What we were encountering was the bigger problem with trying to understand art in a more historically realistic way. The general history that you need for context is messed up in the same ways that the art is. It's brilliant in a dark way - History! legitimates the Art! and the Art! provides evidence for the History!.

That means toggling between the Renaissance - the art and the history - and general observations about the modern academy and history-making. Then Leonardo and some speculation on genius in history.

Part II will look at the art in detail. There's just too much to deal with to do that justice in one post.

Part II will look at the art in detail. There's just too much to deal with to do that justice in one post.

First, the Renaissance is a "period" - period meaning one of the pieces that general timelines are made of. Periods are needed to organize and keep track of broad-scale histories but fail when used to define specifics. Timelines are sequences of periods that tell the broad general history - it's pretty much abstracting a clear narrative thread out of the noise of the historical record. Necessary. But necessarily subjective. Abstracting a narrative thread is another way of saying 'telling a story' and that depends on the storyteller.

The Renaissance that we've been presented with as a period is a spot in the dominant narrative of modern History!. This story is a dim-witted fairy tale based on irresolvable internal contradictions that we’ve been going on about since our early Marxism posts. It's a modern construction and modernity is based on the inverted pretense that the mutually exclusionary coexist. You can’t have teleological progress in history and pure materialism as a state of being. They’re mutually exclusive. But Modernism and Marxism both require them - which is how you know that their claims are hollow lies and their only aim power. They just define the terms differently. Click for an earlier post where we go into this in relation to modern culture. Quick recap.

The Renaissance that we've been presented with as a period is a spot in the dominant narrative of modern History!. This story is a dim-witted fairy tale based on irresolvable internal contradictions that we’ve been going on about since our early Marxism posts. It's a modern construction and modernity is based on the inverted pretense that the mutually exclusionary coexist. You can’t have teleological progress in history and pure materialism as a state of being. They’re mutually exclusive. But Modernism and Marxism both require them - which is how you know that their claims are hollow lies and their only aim power. They just define the terms differently. Click for an earlier post where we go into this in relation to modern culture. Quick recap.

Teleological history proposes that history has an ultimate purpose or goal that it is moving towards.

There is a guiding “force” of some kind governing what seems like random events.

There is a guiding “force” of some kind governing what seems like random events.

In order to guide, the external force has to be greater then the natural events it’s guiding. Literally super-natural

That’s diametrically opposed to materialist Flatland ontologies where creations of life and world are presented as random happenstance.

The assumptions are atheistic.

The assumptions are atheistic.

Rule out the possibility of a guide and randomness is the only alternative.

You either have the random series of events that we see in atheistic materialist thinking or you have guiding, literally super-natural teleologies. Like a condition of progress as a natural state. There’s exactly no other option. You have to pick one.

The material world is murky, but abstracts can be as clear as black and white. Atheist materialism and historical teleology are such things.

And while you’re at it, might as well add in how to make a value judgment mean more than preference in an intellectually coherent materialist ontology.

One of the problems that the Band faces is that the fundamental errors in Modernist and Postmodernist thought are so basic but so ingrained that simply stating them makes us sound insane. One sentence about the mutual exclusivity of teleology and materialism vs. the millions and millions of pages of post-Enlightenment learned cultures. It doesn’t matter that we are objectively correct and the millions of pages objectively wrong.

Idiocy aside, materialist teleology was the coin of the Modern era – the Marxist and Capitalist versions are equally intellectually retarded if different in practical evil. And the part of the Renaissance as the pivot from blind superstition towards… well… incoherent blind faith in impossible things.

It’s why Postmodernism was a crisis. It exposed the bubble of calcified secular transcendent lies without offering anything in its place. Except power.

Hollowness behind the Neoclassical grandeur.

Hollowness behind the Neoclassical grandeur.

Because people want to still cling to the shiny fake Modernist dream, postmodernism was viewed with hostility for the wrong reasons. It should have been a reminder that the glass was darkling and the valley in shadow all along - of course the idea of True knowledge in finite human minds was self-evidently inane. But the narrative-huffers were too far gone into self-idolatry.

Vanity and pride as causes are another thing that seems absurdly simplistic. But what else can account for such a wholesale commitment to such an obvious pack of nonsense?

Vanity and pride as causes are another thing that seems absurdly simplistic. But what else can account for such a wholesale commitment to such an obvious pack of nonsense?

Jan Vermeulen, Vanitas Still Life, 1654, oil on panel, private collection

The vanitas type of painting is a still-life where the objects represent the fleeting and pointless vanity of worldly things. This is a good one, with all kinds of "vanities" discarded around death symbols. The 17th century was when these were really popular, but artists are still painting vanitas themes today.

The name is a reference to Ecclesiastes. Like that book they emphasize the soul over bodily pleasure. Unfortunately, vanity, vanity. all is vanity is a hard sell in Flatland, where love and happiness are measured in stuff. Or prestige. It is a narrow gate.

The vanitas type of painting is a still-life where the objects represent the fleeting and pointless vanity of worldly things. This is a good one, with all kinds of "vanities" discarded around death symbols. The 17th century was when these were really popular, but artists are still painting vanitas themes today.

The name is a reference to Ecclesiastes. Like that book they emphasize the soul over bodily pleasure. Unfortunately, vanity, vanity. all is vanity is a hard sell in Flatland, where love and happiness are measured in stuff. Or prestige. It is a narrow gate.

The vanitas is an unsettling theme - it's supposed to be. The pull of worldly things is so strong that strong measures are called for to break through. And if that was the case with 1600s-level stuff and dancing lights... But if we aren't honest about how powerful vanity - and the related sin of pride - are in distorting our most fundamentally basic world view, we will always be vulnerable to the most simpleminded of deceptions. Like they used to say back in the day, get real.

Art! follows the same fake vanity-driven model of Progress! as modern history in general. The Renaissance is where we see it start – the fall and rebirth model connects human-level improvements in the knowledge base or technical abilities to abstract-level teleologies in historiography. The false equivalence: because we progress in specific goals, progress as a state of Being drives the world along supernatural rails. And it gets even better. Because we have transubstantiated progress out of human affairs to the perfect world of abstraction, we no longer need concern ourselves with the problems that real material progress has to contend with. Like distorting human subjectivities or... gasp... regress.

And like the larger culture, art follows the path of corruption and perversion into postmodern chaos and collapse. The official story takes the gradual degradation of art and it’s replacement with Art! and peddles this abomination as history.

Edouard Manet, At the Cafe, 1878, oil on canvas, Oskar Reinhart Art Collection, Winterthur, Switzerland

Like Manet’s alcoholic degenerates and dead eyed whores. Consider the level of artistic brilliance on display across the West in the 19th century. Look at our collected art posts up above for a small sampler. Now, consider the social and psychological health of someone pushing this instead.

Like Manet’s alcoholic degenerates and dead eyed whores. Consider the level of artistic brilliance on display across the West in the 19th century. Look at our collected art posts up above for a small sampler. Now, consider the social and psychological health of someone pushing this instead.

The official story on Manet - if you've ever wondered about that hack turd. The flat, patchy style is supposed to move away from false "representation" towards a “pure” medium. Remember, Modernism is tied to the unspeakably retarded lie about "autonomy". So by looking more like splashed paint and less like a picture, Manet is Progress!ing. Ditto the ugliness - it's replacing "outdated" notions about art with poorly rendered low-class urban dysfunction. The satanic have always warred on beauty.

The inversion of culture means failure and mediocrity become heroic. Which is how this becomes art...

The inversion of culture means failure and mediocrity become heroic. Which is how this becomes art...

Arshile Gorky, Agua del molinode las flores, (Water of the Flowery Mill), 1944, Guggenheim, Bilbao

It’s “discourse”.

Foucault wasn’t wrong about it being fake and power. Useful liar that he was, there has to be an element of truth. His lie was that the fake was reality and not an illusion taken in place of reality.

In reality, you aren't a helpless victim of discourse unless you empower your own enslavement.

It’s “discourse”.

Foucault wasn’t wrong about it being fake and power. Useful liar that he was, there has to be an element of truth. His lie was that the fake was reality and not an illusion taken in place of reality.

In reality, you aren't a helpless victim of discourse unless you empower your own enslavement.

The Band is tracing how the gap between art and Art! happened so we can restore a truer path for the future. We noted that the 20th century is too close, dark, and riddled with deception for us to find pathways much below the surface. Which is fine, because to no one's surprise, this is when what was art also becomes twisted beyond rational analysis. The difference is that we have to live in the history. The art? Go back, find the thread, and bypass the whole fetid pathless wasteland. It's why we are rethinking the timeline based on the materials we have, but without the distortions that arise from juvenile fairy tales like Progress!.

Bringing us to...

The High Renaissance is usually defined from somewhere between the 1480s and 1500 to around 1520. In reality it was a localized art movement that came to stand for “the Renaissance” period as a whole, which in turn became the moment everything changed. Other than the tidy appeal of 1500 as a round number, there is no pressing reason for this.

As we saw in the graphics in the last few posts, what got compressed into that moment was actually a long time. A century is long – think of the 20th century. And before pointing out that the pace of change is faster now, consider that roughly a century separates the crowning of Constantine from Attila’s sack of Rome.

As we saw in the graphics in the last few posts, what got compressed into that moment was actually a long time. A century is long – think of the 20th century. And before pointing out that the pace of change is faster now, consider that roughly a century separates the crowning of Constantine from Attila’s sack of Rome.

In classical rhetoric it’s synecdoche. One piece of a complex whole – in this case a big historical picture – pulled out and treated as if the whole thing.

Put aside pre-conceived periods and you don't see an obvious reason to identify this as a pivotal moment. What you do see is a series of big technological changes from the later Middle Ages through the Scientific Revolution. Before that was jacked by rationalism. The cumulative weight of these innovations does transform society, but not overnight, or even during a 30 year period of inflection.

Consider the following, when they appeared, and their impact on society and culture.

Consider the following, when they appeared, and their impact on society and culture.

The heavy plough

Oxen pulling a plough from an illuminated bestiary, 2nd quarter of the 13th century, British Library, Royal 12 F XIII f. 37v

A practical inventions that isn't sexy. But a big part of the agricultural revolution that was a needed for the Western technological leap. One site calls the 9th century to the 13th a time of unprecedented productivity growth and "the most significant agricultural expansion since the Neolithic revolution".

Sounds important. Also not Renaissance.

Glasses

A practical inventions that isn't sexy. But a big part of the agricultural revolution that was a needed for the Western technological leap. One site calls the 9th century to the 13th a time of unprecedented productivity growth and "the most significant agricultural expansion since the Neolithic revolution".

Sounds important. Also not Renaissance.

Glasses

Type 1 and Type 3 eyeglasses from Kloster Wienhausen (near Celle), Germany, 13th century

Optics were an area of ancient interest that was developed by medieval Muslims and transmitted into the medieval West. It was here, as with so many things, that the potential was finally realized.

Eyeglasses seem to have been invented in Italy in the second half of the 13th century. The early frames were wood like these ones. Corrective lenses are a pretty major shift. But not Renaissance.

Double-entry bookkeeping

Optics were an area of ancient interest that was developed by medieval Muslims and transmitted into the medieval West. It was here, as with so many things, that the potential was finally realized.

Eyeglasses seem to have been invented in Italy in the second half of the 13th century. The early frames were wood like these ones. Corrective lenses are a pretty major shift. But not Renaissance.

Double-entry bookkeeping

Cocharelli, Averice from a Latin prose treatise on the Seven Vices; bankers in an Italian counting house, circa 1340

The actual invention of the concept has older roots, but recognizable modern accounting began in 13th century Italy. Like the glasses.

Leonardo's friend, the mathematician and polymath Luca Pacioli wrote the first major treatment of accounting in the 15th century. More Renaissance theorizing of already existing things. But the basis of modern finance? Not Renaissance.

Urbanization

The actual invention of the concept has older roots, but recognizable modern accounting began in 13th century Italy. Like the glasses.

Leonardo's friend, the mathematician and polymath Luca Pacioli wrote the first major treatment of accounting in the 15th century. More Renaissance theorizing of already existing things. But the basis of modern finance? Not Renaissance.

Urbanization

Matthew Paris, depiction of London from his Historia Anglorum, Chronica majora, Part III, 1250-1259

Urbanization patterns took off in the 12th-13th centuries, with cities becoming centers of commerce, government, and religion. Click for a link on general prosperity in the late Middle Ages.

Here's an old friend from the medieval posts and what has become a major globalist hub. London and many other cities took form in the medieval times. That is, not the Renaissance.

Urbanization patterns took off in the 12th-13th centuries, with cities becoming centers of commerce, government, and religion. Click for a link on general prosperity in the late Middle Ages.

Here's an old friend from the medieval posts and what has become a major globalist hub. London and many other cities took form in the medieval times. That is, not the Renaissance.

Papermaking

Early South English Legendary, probably late 14th Century, paper, St. John’s College Library, Cambridge

Maybe finance and urbanization are too broad. How about paper? Cheap printing material was critical for the growth of the modern West. Paper had been invented in China in ancient times then passed into the Muslim world. The Moors were making paper in Spain in the 12th century and it spread through Europe from there. Vellum and parchment were finer, but vastly less practical. Click for a link on the early history of paper.

Neither the Chinese origins nor medieval arrival were Renaissance.

Maybe finance and urbanization are too broad. How about paper? Cheap printing material was critical for the growth of the modern West. Paper had been invented in China in ancient times then passed into the Muslim world. The Moors were making paper in Spain in the 12th century and it spread through Europe from there. Vellum and parchment were finer, but vastly less practical. Click for a link on the early history of paper.

Neither the Chinese origins nor medieval arrival were Renaissance.

Oil paint

Jan van Eyck, The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, oil on panel, c. 1435. Louvre, Paris

How about something more artistic? Oil paint is the most versatile and expressive medium and a key to Leonardo's radical achievements. It was invented in the Middle Ages and refined into an essentially modern form in early 15th century Flanders by painters like Van Eyck. You can see the improved luminosity and detail over older medieval media.

It was central to Renaissance art. But still not Renaissance.

How about something more artistic? Oil paint is the most versatile and expressive medium and a key to Leonardo's radical achievements. It was invented in the Middle Ages and refined into an essentially modern form in early 15th century Flanders by painters like Van Eyck. You can see the improved luminosity and detail over older medieval media.

It was central to Renaissance art. But still not Renaissance.

The Telescope

Two of Galileo's first telescopes from the early 17th century, Museo Galileo, Florence

And after the Renaissance. Galileo was an early exploiter of telescopic technology, but the first example was made by a Dutchman a year or two before his versions. By 1611, Kepler had significantly improved the design.

Telescopes are just one example of the optics and instrumentation that have extended our senses. They involved the combined efforts of many minds. But post-Renaissance still isn't Renaissance.

And after the Renaissance. Galileo was an early exploiter of telescopic technology, but the first example was made by a Dutchman a year or two before his versions. By 1611, Kepler had significantly improved the design.

Telescopes are just one example of the optics and instrumentation that have extended our senses. They involved the combined efforts of many minds. But post-Renaissance still isn't Renaissance.

We could continue but the point is clear. Pick the type, scale, or level of big invention and there are no innovations of comparable significance around 1500 in Italy outside of art.

The biggest innovation of all happened a bit earlier - around 1440 - in Gothic Germany. That's Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the movable type printing press. From the perspective of Progress! towards modernity, there's really nothing more significant. It's the capstone to medieval inventiveness and with paper as a material transformed civilization. It's tempting to see the Renaissance as like the 60s - when a huge legacy of prosperity was pissed away on mysticism, feelings, and vanity.

The biggest innovation of all happened a bit earlier - around 1440 - in Gothic Germany. That's Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the movable type printing press. From the perspective of Progress! towards modernity, there's really nothing more significant. It's the capstone to medieval inventiveness and with paper as a material transformed civilization. It's tempting to see the Renaissance as like the 60s - when a huge legacy of prosperity was pissed away on mysticism, feelings, and vanity.

Replica of Gutenberg's invention. The apparatus was based on a wine press with a holder for the movable type. It took some time to prepare, but once the type was set it could replicate text at previously unimagined rates. The dissemination and storage of information were completely changed.

It wasn't Renaissance. In fact, quite the opposite. What we call the Renaissance was an effect of printed material.

We aren't just overstating the 1500 thing. Reniassance is a word with a very specific history. It means cultural improvement through rebirth - of classical culture in particular - and was a concept invented by Italian humanists. What is there about any of these inventions - including Gutenberg's - that has anything to do with ancient culture? They're either new discoveries or non-Western imports that get developed in new directions. And Gutenberg was hardly a humanist. Far from it - he was a huckster looking to recover losses on a speculative venture into pilgrimage memorabilia.

His revolution in information technology was culturally transformative. But it has nothing to do with the humanistic ideas associated with the Renaissance as a movement.

It wasn't Renaissance. In fact, quite the opposite. What we call the Renaissance was an effect of printed material.

We aren't just overstating the 1500 thing. Reniassance is a word with a very specific history. It means cultural improvement through rebirth - of classical culture in particular - and was a concept invented by Italian humanists. What is there about any of these inventions - including Gutenberg's - that has anything to do with ancient culture? They're either new discoveries or non-Western imports that get developed in new directions. And Gutenberg was hardly a humanist. Far from it - he was a huckster looking to recover losses on a speculative venture into pilgrimage memorabilia.

His revolution in information technology was culturally transformative. But it has nothing to do with the humanistic ideas associated with the Renaissance as a movement.

Precuniform tablet, Uruk III era, late 4th millennium BC., Louvre

Printing is an epochal change in image technology – one of a few that radically alters the nature of human life on the civilizational level. The only prior comparables would be the inventions of writing in the early Bronze Age and of language itself - whenever that was.

There are hypotheses that there are older writing systems, but the Sumerian pre-cuniform is the earliest that we can be sure of so far.

Printing is an epochal change in image technology – one of a few that radically alters the nature of human life on the civilizational level. The only prior comparables would be the inventions of writing in the early Bronze Age and of language itself - whenever that was.

There are hypotheses that there are older writing systems, but the Sumerian pre-cuniform is the earliest that we can be sure of so far.

The other examples of infotech transformation on this level are more modern – transmissible audio-video in the 20th century and wherever linked computers are going today.

T.V./video and linked computers...

It’s hard to say where this is going from the middle. The movie/t.v. and video world sort of melded into the internet / v.r. world, and the latter is just getting going.

The speed of technical change has rapidly accelerated – that’s the main reason for the myth of universal Progress!.

It’s hard to say where this is going from the middle. The movie/t.v. and video world sort of melded into the internet / v.r. world, and the latter is just getting going.

The speed of technical change has rapidly accelerated – that’s the main reason for the myth of universal Progress!.

The problem was pretending engineering was metaphysics.

This is the level of information technology that the printing press is on. They obviously aren’t all the same – though they do build on each other. But they are more like each other in terms of their transformation of human life than they’re like anything else. A totally new paradigm that sets the tone until the next major one. Writing or carving documents was the way until printing. Printing was refined until video.

Scanning over the history of the later Middle Ages and Renaissance - it is odd how little attention is given the printing press relative to other phenomena - inventions or general cultural. Less likely something nefarious than the printing paradigm being so universal it’s invisible. They don't fully credit writing for early civilization either.

Johannes Gutenberg’s first printing press, Getty Images

All the big cultural changes of the 16th and 17th centuries – from humanism and Reformation to Counter-reformation and Scientific Revolution – were made possible by this unprecedented access to the printed word. The entire knowledge edifice to build advanced civilization – with all the good and ill that entails.

All the big cultural changes of the 16th and 17th centuries – from humanism and Reformation to Counter-reformation and Scientific Revolution – were made possible by this unprecedented access to the printed word. The entire knowledge edifice to build advanced civilization – with all the good and ill that entails.

If there is one invention that stands out for driving the cultural transformations that started in the later 1400s, it’s the printing press. Interesting that it’s “Renaissance” – the Italian humanist “rebirth” of classical letters and values – that gets used to describe this game-changer. If you think about it, it misrepresents to the point of falsehood. What does “classical antiquity” have to do with printing? Or metal plate engraving? Or oil paint? Or papermaking?

Besides, Gutenberg’s first book was a Bible.

Johann Gutenberg, Biblia Latina (Bible in Latin), Mainz: 1455, Otto Vollbehr Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Notice the conflation – the cultural flux during the period that gets called the Renaissance is driven by printing and other technological innovations. When we looked at the emergence of Renaissance humanism in the 14th century, it was a product of the unique culture of the late medieval Tuscan city-states. But printing made it possible for these ideas to spread widely.

Consider the sequence -

Notice the conflation – the cultural flux during the period that gets called the Renaissance is driven by printing and other technological innovations. When we looked at the emergence of Renaissance humanism in the 14th century, it was a product of the unique culture of the late medieval Tuscan city-states. But printing made it possible for these ideas to spread widely.

Consider the sequence -

1. Printing is a revolution in infotech that spreads chaos across the spectrum of ideas and beliefs.

2. The Italian Humanist idea of antique rebirth that gives the Renaissance its name is part of this chaos.

3. So why take “Renaissance” as the term to refer to the entire sprawling cultural transformation?

It has to do with the construction of the historical Progress! narrative. What makes the connotations of "Renaissance" attractive to it is Dark Age / Rebirth model. The historic reality is that the Renaissance period was Christian - overly occult - but that’s irrelevant. What matters is the idea of human-driven recovery based on human-sourced material.

Michelangelo, The Risen Christ, 1515, marble, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome

This statue is a perfect illustration of Renaissance epistemology. It's an obviously Christian subject - Jesus in perfect risen form and carrying the Passion instruments to meditate on. But look at how he is depicted. Pure white marble nude with an idealized body and classical contrapposto stance.

Michelangelo was a perfectly devout Christian who expressed himself through Classically-inspired sculpture. Progress! ignores the subject matter and the act of faith that went into making something like this and highlights the Greco-Roman aesthetics and nudity. Nudity not in the Classical sense of ideal beauty, but as a prophecy of future degeneracy.

This statue is a perfect illustration of Renaissance epistemology. It's an obviously Christian subject - Jesus in perfect risen form and carrying the Passion instruments to meditate on. But look at how he is depicted. Pure white marble nude with an idealized body and classical contrapposto stance.

Michelangelo was a perfectly devout Christian who expressed himself through Classically-inspired sculpture. Progress! ignores the subject matter and the act of faith that went into making something like this and highlights the Greco-Roman aesthetics and nudity. Nudity not in the Classical sense of ideal beauty, but as a prophecy of future degeneracy.

So cherrypick the introduction of secular subject matter and human authority as step one. Then apply this to Enlightenment-era lies to turn the Renaissance "Dark Age" of lost Classical learning into a primitive and superstitious “Age of Faith”. Same structure, just further along the de-moralization slide.

The whole point of rationalism is to remove Christianity from the fabric of Western society. That is the Progress!. It looks like this.

The whole point of rationalism is to remove Christianity from the fabric of Western society. That is the Progress!. It looks like this.

The Renaissance idea of rebirth after Dark Age was the recovery of classical culture in a Christian framework. But it becomes the first part of a longer progression away from logos into solipsism and auto-idolatry. Christianity for secular materialism.

The Enlightenment takes the next step - keeping the solipsism of the Renaissance humanist “man as the measure” but getting rid of God altogether.

The Enlightenment takes the next step - keeping the solipsism of the Renaissance humanist “man as the measure” but getting rid of God altogether.

Just ignore the math...

The historiography isn't “Renaissance” or “Enlightenment” , but a perverse hybrid where parts of both are folded into a larger satanic whole. Call it Progress! historiography. Increasingly sinking into auto-idolatry and solipsism and away from logos. Now we know secular transcendence is an inversion of reality. What if we invert the direction of their fake morality...

The historiography isn't “Renaissance” or “Enlightenment” , but a perverse hybrid where parts of both are folded into a larger satanic whole. Call it Progress! historiography. Increasingly sinking into auto-idolatry and solipsism and away from logos. Now we know secular transcendence is an inversion of reality. What if we invert the direction of their fake morality...

Here’s how it looks as in relation to logos…

Once you see the trajectory, why "Renaissance" gets easy to answer.

Once you see the trajectory, why "Renaissance" gets easy to answer.

The anti-Christianity is obvious. The period next to the invention of printing is called the Renaissance because of all the consequences and cultural change, that is the one that pedestalized non-Christian authority regarding Truth. Secular transcendence doesn't care if Michelangelo or anyone else was Christian. Hence the cherry-picking. Reviving pagan knowledge became the process that was used to crack Christian metaphysics that enabled the secular transcendence.

Antiquity and atheist modernism become the anti-Christian bookends of a historical fiction in two parts. Ancient Scylla on one side, bottomless modern Charybdis on the other.

Antiquity and atheist modernism become the anti-Christian bookends of a historical fiction in two parts. Ancient Scylla on one side, bottomless modern Charybdis on the other.

It’s easy to grasp how absurd and inverted this is, even if you’re totally new to the study of history. Look around. Does real history appear to move like that?

The point of the the modern history story is not to come up with the best summary of what happened. If that were the case, a more accurate representative synecdoche would have been chosen. Take “Reformation” for example – the word, not the religious movement it came to define. If you used it for the whole period, you could throw the Humanist movement in letters, the Protestant Reformation, the Counter-reformation, the Age of Discovery, the Scientific Revolution, and all the others into one period called reforming and transforming the ancient pillars of Christianity and Classicism.

Titian, Equestrian Portrait of Charles V, 1548, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Among Titian's accomplishments - the formal mounted official portrait. You can also see the luminous finish of the oil paint - in the sky and off the armor.

You could look politically at the rise of nation-states to power, from the Avignon Papacy to the Treaty of Westphalia as a 350-year span. The nations of the West are the third pillar of it. You could call it “The Nationalization” of the other two more ancient pillars. Anything makes more sense then “the rebirth of antiquity”.

Among Titian's accomplishments - the formal mounted official portrait. You can also see the luminous finish of the oil paint - in the sky and off the armor.

You could look politically at the rise of nation-states to power, from the Avignon Papacy to the Treaty of Westphalia as a 350-year span. The nations of the West are the third pillar of it. You could call it “The Nationalization” of the other two more ancient pillars. Anything makes more sense then “the rebirth of antiquity”.

Unless the anti-Christianity is the reason.

It is the path of inversion. The “rebirth” of Hell-bound pagan ignorance and vanity and winding up with a total inversion where Logos – the proper alignment of knowledge and ontology – is superstition. Meaning Progress! isn’t only the metaphysical inverse of Christianity, it’s its diametric enemy by the terms of its very existence. Logos - and by extension the West – is a conceptual Dark Age that only the pen of light of doing what thou wilt with Enlightenment reason can overcome.

Well, reason and stuff...

Now, pause and consider for a moment - think how obviously and self-evidently fake Progress! is on every level. Then ponder the implications for Christianity…

So the “rebirth of antiquity” and Enlightenment secular transcendence are just steps along the same fake teleology that kicks in around 1500. This is a conclusion we’ve reached in much earlier posts, but it was worth reiterating it here. Especially with the direct tie-ins to the art. It’s so retarded it’s irritating, yet somehow pointing it out makes us crazy.

Like a fox...

Like a fox...

So if this High Renaissance isn’t a cultural change, what is it?

The short answer is that it’s an artifact of how history is made. Not historiographic theory, but the actual practice of researching and writing. In this case, the impact of Art History as a discipline on the perception of what happened in the past.

Marco Battaglini, NIHIL DIFFICILE AMANTI PUTO, 21st century, mixed painting

We don’t comment much on the formal field of Art History – it’s incoherent despite being part of the academy since Burckhardt.

Making a place for visually-minded people to tackle the artistic contributions to history and culture seems sensible enough. But like all of the modern “discourses”, it was victimized first by post-Enlightenment secular transcendence then postmodern uselessness. The art is still there though.

Making a place for visually-minded people to tackle the artistic contributions to history and culture seems sensible enough. But like all of the modern “discourses”, it was victimized first by post-Enlightenment secular transcendence then postmodern uselessness. The art is still there though.

Parts of Art History are useful. The Band does owe a debt to those generations of art historians for the pictures and information that we use. It’s the big picture stuff that is toxic - like what art means in society and all the Modernism rubbish that legitimates the garbage cluttering up today’s museums.

Now for the how history is made part. Timelines need big signature moments to symbolize changes or represent the main characteristics of a period. More synecdoche – Harper’s Ferry, Kitty Hawk, Woodstock.

Now for the how history is made part. Timelines need big signature moments to symbolize changes or represent the main characteristics of a period. More synecdoche – Harper’s Ferry, Kitty Hawk, Woodstock.

The use of synecdoche in periods and timelines is perfectly natural. But it also assigns those things that are chosen special significance based on their importance to the narrative.

In some cases, this importance is self-evident – like Gutenberg’s press. Sometimes it's media glamour.

The signature markers of the “High Renaissance” of around 1500 - the big signature timeline synecdoches - are works of art.

Think about it - we've gone through the big discoveries. When is the Renaissance in literature? Dante and Petrarch were active in the 13th and 14th centuries and Shakespeare around 1600. Who in between is comparable?

“Oh, but the English Renaissance is later…”

In some cases, this importance is self-evident – like Gutenberg’s press. Sometimes it's media glamour.

The signature markers of the “High Renaissance” of around 1500 - the big signature timeline synecdoches - are works of art.

Think about it - we've gone through the big discoveries. When is the Renaissance in literature? Dante and Petrarch were active in the 13th and 14th centuries and Shakespeare around 1600. Who in between is comparable?

“Oh, but the English Renaissance is later…”

John Gilbert, The Plays of William Shakespeare, 1849, oil on canvas, New York

Shakespeare - the Michelangelo of the English Renaissnace lived from 1564 to 1616. That is, not citrca 1500.

Politically, there is no unusually significant developments. The important changes had already happened. The formation of the European nations was underway. The innovative city-state republics like Florence and Siena that birthed the Renaissance were unique medieval socio-political inventions. Marsilius of Padua theorized a popular basis for governmental legitimacy in his Defensor Pacis of 1324. Cola di Rienzo’s populist Roman uprising was also early 14th century.

Shakespeare - the Michelangelo of the English Renaissnace lived from 1564 to 1616. That is, not citrca 1500.

Politically, there is no unusually significant developments. The important changes had already happened. The formation of the European nations was underway. The innovative city-state republics like Florence and Siena that birthed the Renaissance were unique medieval socio-political inventions. Marsilius of Padua theorized a popular basis for governmental legitimacy in his Defensor Pacis of 1324. Cola di Rienzo’s populist Roman uprising was also early 14th century.

The big exception in political thought would be Machiavelli (1469-1527). But one bright light doesn't make a movement, and he doesn't have the immediate impact to represent a synedoche signature moment at this time.

Philosophically, the Renaissance is a desert. The big names circa 1500 were Hermetic nonsense-spinners like Pico della Mirandola and his mentor Marsilio Ficino - the second is well known to us from our occult posts. Second-rate frauds who are only remembered because they were the “philosophy” at the time of the Renaissance – that is, when the signature art landmarks were made.

Corpus Hermeticum, first Latin edition, by Marsilio Ficino, 1471, Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam

We've seen enough of Ficino. Just a reminder that he was active at this time, and in his old age overlaps with Michelangelo in the Medici court.

We've seen enough of Ficino. Just a reminder that he was active at this time, and in his old age overlaps with Michelangelo in the Medici court.

If we want to be really technical, the big changes at the time were in humanism as well as art. Rome was asserting itself as the center of a new form of Christian humanism as well as fine art and architecture. But the Renaissance form of humanism didn’t go anywhere before being chased out of polite society and metastasizing into new kinds of inversion. Our Hermeticism posts are a good indication of how that looks. Click for part 1, part 2, part 3. The second one is the main Renaissance one.

So that leaves the art.

It should be noted that Renaissance art is a huge business today.

So that leaves the art.

It should be noted that Renaissance art is a huge business today.

Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi, around1500, oil on panel, private collection

The most expensive painting ever sold, this pulled $450.3 US in 201 - that's over $470 million today. Originally intended as the centerpiece of a Saudi museum, the precise whereabouts of the picture and the future plan are uncertain.

The weird surface is the result of bungled cleaning. Historical methods removed paint off the surface leaving a faded effect. That mattered less than this being an original Leonardo - one of fewer than 20. It's haunting and evocative qualities were things Leonardo seemed able to create from his imagination.

The most expensive painting ever sold, this pulled $450.3 US in 201 - that's over $470 million today. Originally intended as the centerpiece of a Saudi museum, the precise whereabouts of the picture and the future plan are uncertain.

The weird surface is the result of bungled cleaning. Historical methods removed paint off the surface leaving a faded effect. That mattered less than this being an original Leonardo - one of fewer than 20. It's haunting and evocative qualities were things Leonardo seemed able to create from his imagination.

We’ve already seen the beginnings of a theoretical self-consciousness in the 15th century – the High Renaissance blows this open into new perspectives that set the course for the future.

It looks like the idea of the High Renaissance as a historical period is the result of thousands of pages of Art History piling up around these famous landmarks. The history, philosophy, politics, etc. at the time when the Mona Lisa and the Sistine Chapel were made.

It looks like the idea of the High Renaissance as a historical period is the result of thousands of pages of Art History piling up around these famous landmarks. The history, philosophy, politics, etc. at the time when the Mona Lisa and the Sistine Chapel were made.

Art historians' interest in the big landmarks of art create masses of studies and scholarship around them. Bits of context like magnetic filings attracted around the art work lodestones, creating the impression of a distinct and important period. Although the only thing making the filings significant is their coexistence with the art works.

The roots of the Renaissance as a historical construct and Art History as a discipline are entwined – both emerging from the academic world of Burckardt and his peers. Art was integral to the definition and construction of the Renaissance as an intellectual structure from the jump. This is why we pay so much attention to historiography as well as what happened.

The real past is always beyond us. We have accounts and artifacts of different kinds that let us reconstruct what was going on. But reconstruction isn't the original, and history is narrative. Understanding how and why that narrative was put together the way it was partly counters the distortion effect. How Marxist historian might do something useful - like uncover some documents or date an event - before spiraling into self-fluffing lies

When secular transcendent globalists turned the Renaissance into a model of fake progress, they were adopting signature art markers and whatever contextual non-entities happened to coexist. Mediocre Roman churchmen that wouldn’t have been remembered enough to be soon forgotten in the Holy Roman Empire were immortalized through art historical research.

Canonical works like this one however are among the most famous and recognizable images in the world. They have attracted attention first from around Italy, then Europe, and now the world. Of course researchers and scholars are going to be curious about the world where they came from. And it's not just that they're super attractive. As we've just explained, they're the only attractors really worth noting if you were going to to posit a distinct, High Renaissance bubble world.

They're the central pillars, the period falls into place around them.

They're the central pillars, the period falls into place around them.

Not that there's anything wrong with this... if we're constructing an art history. The High Renaissance is one of the most creative artistic movements anywhere ever. And it is nice to be able to look up where these came from and what they mean. The problem is when we take artistic landmarks as the tentpoles to posit an imaginary historical moment when everything changed. Because rejecting logos for secular transcendence. Everything did change, but neither right then nor for the better. The conclusion?

Which is ok. We're tracing the arts of the West anyhow.

When we say start with the art, we don't mean the theory. It's true that we've described the Renaissance as the stage in the development of Art! when it first becomes theoretically self-conscious. But we also explained in the last post that the written theory like Vasari comes later. After the new direction in art has been charted. Because the theory of the High Renaissance is developed by the artists themselves. The written commentary is a reaction to theoretical moves that were already made in the paintings and sculptures. This even applies to the presence of more philosophical concepts in the artworks. It's a big reason why it is hard to interpret these guys - they were writing formulas, not following them. Take the Neoplatonic strains in Michelangelo - it's a common topic in discussions of his art.

To get the High Renaissance, we have to start with the art

Which is ok. We're tracing the arts of the West anyhow.

When we say start with the art, we don't mean the theory. It's true that we've described the Renaissance as the stage in the development of Art! when it first becomes theoretically self-conscious. But we also explained in the last post that the written theory like Vasari comes later. After the new direction in art has been charted. Because the theory of the High Renaissance is developed by the artists themselves. The written commentary is a reaction to theoretical moves that were already made in the paintings and sculptures. This even applies to the presence of more philosophical concepts in the artworks. It's a big reason why it is hard to interpret these guys - they were writing formulas, not following them. Take the Neoplatonic strains in Michelangelo - it's a common topic in discussions of his art.

Michelangelo, Bearded Slave and Atlas Slave, 1530-1534, marble, Accademia, Florence

Two of the unfinished prisoners or slaves for the tomb of Pope Julius II. Even the names are made up after the fact - it's not clear what these were supposed to be. The similar-looking nudes on the Sistine Chapel are not symbolically clear. Click for the link to the Accademia museum in Florence where these are kept.

These get interpreted as perfect form struggling to free itself from brute matter. Not hard to see why.

Two of the unfinished prisoners or slaves for the tomb of Pope Julius II. Even the names are made up after the fact - it's not clear what these were supposed to be. The similar-looking nudes on the Sistine Chapel are not symbolically clear. Click for the link to the Accademia museum in Florence where these are kept.

These get interpreted as perfect form struggling to free itself from brute matter. Not hard to see why.

Michelangelo, Young Slave and Awakening Slave, 1530-1534, marble, Accademia, Florence

The terms slave and prisoner reflect the Neoplatonic interpretation be describing the subjects as trapped and struggling. There was no evidence that this was their intended role on in the tomb project. They were never finished and the Julius tomb was completed in a vastly reduced form, so there's no way to know.

The terms slave and prisoner reflect the Neoplatonic interpretation be describing the subjects as trapped and struggling. There was no evidence that this was their intended role on in the tomb project. They were never finished and the Julius tomb was completed in a vastly reduced form, so there's no way to know.

It's easy to see the metaphorical struggle of the higher state of intellect or spirit to free itself from base material constraints. But there was no Neoplatonic school of art. And Michelangelo shows certain Neoplatonic leanings but was neither a humanist nor a Neoplatonist. Any presence of this in his art would have come from his exposure to humanist learning in the Medici household that and the general presence of the ideas in the air at the time. It's later historians who look at Michelangelo, study the contemporary philosophy, and conclude that he was channeling the ideas visually. But no one writes about it until afterwards. It's speculative - we can't really know what ideas an artist was influenced by if he doesn't tell us - and distorts our larger timelines.

There is also the issue of his working method. The Accademia link cites Vasari:

‘[…] It is as if one were taking a figure, made of wax or other solid material, a figure which one would then put stretched out in a bowl of water, water which is naturally flat and smooth at the surface, after which one would gradually lift the figure to the surface, so that first the most protruding parts would emerge, while the underlying parts, i.e. the lowest parts, would remain hidden, until the figure came to light in its entirety in this way.’

An informative travel blog with excellent pictures relates the quote to Michelangelo's St Matthew - another unfinished marble statue and block.

Michelangelo, St. Matthew, left unfinished in 1506, Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence

We reproduced the picture here because it is such a great illustration of Michelangelo's technique. It like he's draining water to show a submerged figure. Except it's marble. Are Neoplatonic interpretations able to coexist with working method? We don't see why not - as long as claims to know what Michelangelo was thinking are avoided. And that they are kept as part of the cultural background noise and not put forth as the main theme. You could just as easily put together an Aristotelian metaphor about the union of form and matter in things.

We reproduced the picture here because it is such a great illustration of Michelangelo's technique. It like he's draining water to show a submerged figure. Except it's marble. Are Neoplatonic interpretations able to coexist with working method? We don't see why not - as long as claims to know what Michelangelo was thinking are avoided. And that they are kept as part of the cultural background noise and not put forth as the main theme. You could just as easily put together an Aristotelian metaphor about the union of form and matter in things.

Since the High Renaissance is defined by works of art, and since the works of art are singularly influential, and since we're tracing the art of the West, the question is, what is it that these artists were doing? What was their relationship to the larger culture? Their impact on art – both Art! and in reality?

Titian, Assumption of the Virgin or Frari Assumption, 1515–1518, oil on canvas, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari

How High Renaissance artists brought beauty into the world, drew man closer to God, and honored the Creator by creating in His image.

Like Titian's coming out party. This huge painting blazes with light and energy, with a fantastic foreshortened God the Father above.

We’ll see how it goes.

There isn’t going to be a recap of Renaissance art. There’s too much material, and we’re looking for broad patterns. Since it was a handful of cutting edge geniuses that were driving the innovations, lets spend the rest of the post looking at the first one. We’ve spent a lot of time on the general reflections, and it takes time to do these guys anything like justice. So we’ll start with Leonardo.

Leonardo

The first thing that we noticed is that Leonardo da Vinci is more important in these historical processes then we thought. Both what happened and how the period was conceived in modern history. Start with a marker: if the Renaissance is a localized art movement extrapolated to total cultural transformation, then Leonardo is the archetype and instigator.

Leonardo

The first thing that we noticed is that Leonardo da Vinci is more important in these historical processes then we thought. Both what happened and how the period was conceived in modern history. Start with a marker: if the Renaissance is a localized art movement extrapolated to total cultural transformation, then Leonardo is the archetype and instigator.

The history radiates out from him like ripples on a pond.

The problem with trying to draw some more specific conclusion about him is that he’s beyond us. We can’t get a complete handle on him. Intellectually so we’re left with partial impressions and a footprint on the historical record. Not full understanding, but not nothing.

Leonardo’s defining characteristic is his vast intelligence. We could have said his manual dexterity, but that’s less rare than his mind. He appears to be the smartest artist that we know of, and the outstanding intellect in the Western tradition between Aquinas and Newton. Some have called him the most inventive person of all time.The footprint is an impressive one. There's a reason he's described as polymath...

Leonardo’s defining characteristic is his vast intelligence. We could have said his manual dexterity, but that’s less rare than his mind. He appears to be the smartest artist that we know of, and the outstanding intellect in the Western tradition between Aquinas and Newton. Some have called him the most inventive person of all time.The footprint is an impressive one. There's a reason he's described as polymath...

This is interesting company, because like them, the Band had come to consider Leonardo an “epochal mind”. This isn’t a new Band term that we're going to keep using – it’s way too subjective, ill-defined, and blurry for that. Even the name is terrible. It’s just an idea we’ve started entertaining about the role of the extremity of genius in shaping history - at the time and as constructed by later historians. It isn’t a “theory of history” as much an historical phenomenon. Master theories of history have proved as useless as the one-trick ponies thinkers shilling them. It’s a factor that influences the course of events.

The premise – some extreme cognitive outliers become so transforming, so influential, so… paradigmatic that they shape the mentality of the era that follows and its treatment in later history. They are so instrumental in creating history that they stand for it.

The premise – some extreme cognitive outliers become so transforming, so influential, so… paradigmatic that they shape the mentality of the era that follows and its treatment in later history. They are so instrumental in creating history that they stand for it.

Claude-Aimé Chenavard, reliefs by Antonin Moine, Vase of the Renaissance, 1832, Porcelaine de Sèvres, Louvre

This line of thinking is coming from reflecting on Renaissance artists and their influence on the art of the West. How they became practical models to learn from and imitate and more general archetypes of art at the same time. Processes and aura from artistic genius and its impact.

This line of thinking is coming from reflecting on Renaissance artists and their influence on the art of the West. How they became practical models to learn from and imitate and more general archetypes of art at the same time. Processes and aura from artistic genius and its impact.

Like how artists copied and learned from Leonardo’s art and his persona became generally symbolic of “artist”. This fantastic vase shows it.

The Mona Lisa was painted in Florence, but Leonardo brought it to France, where he kept tinkering with it and where he and the king spend a lot of time together. So It’s misleading but not necessarily false.

The important thing is the two aspects of Leonardo – model artist and technical model for artists. Now remove the artistic. You get processes and aura from a figure connected to the creation of a mentality who exemplifies its processes and methods and embodies its identity and essence.

The problems with the epochal mind idea are already obvious. How do you measure impact or mentality? What’s the criteria? Who makes the cut and how can we be sure? Then there’s the whole problem of modernity – with all the wizardry, lies, and deceptions of the centralized narrative engineering that comes with globalism.

By any normal empiricism, Tesla would have been an epochal mind for the 20th century. The problem is that we find the 20th century to be too opaque. Too much deception an monstrousness and too recent to sift it out. There's a reason why we stick to mass culture - things we can see - when writing about historical things past the nineteen-teens.

But it is still worth considering. If for no other reason than to find a way to get at figures whose intellects make them impossible to grasp directly. Those IQs 6-7 or more standard deviations above the mean coupled with commensurate accomplishment. Like Leonardo. Rub him up against his historical peers and see what shakes out.

Aristotle is our prototype. A genius of scope impossible to sum up and a subsequent impact of comparable magnitude. In domain after domain Aristotle mapped paths of future understanding. No point getting into specifics – the whole is too overwhelming for any attempt at concise granularity. And the big picture is as impossibly broad as it is creative. Causality in ontology, literary criticism, formal logic, political theory, empiricism, rhetoric… even the big domains are too many and varied to sum up.

Stick to general observations and compensate for our limits with historical hindsight. What’s going on here?

Aristotle’s corpus is also a synthesis of ancient knowledge from the Ionian Enlightenment to Plato with whatever occultisms trickled in from Egypt and the Middle East, plus all the cultural achievements of Classical Greece. From this comprehensive starting material, he churns out insight and conclusion after insight and conclusion that set new directions for future thought.

Aristotle’s corpus is also a synthesis of ancient knowledge from the Ionian Enlightenment to Plato with whatever occultisms trickled in from Egypt and the Middle East, plus all the cultural achievements of Classical Greece. From this comprehensive starting material, he churns out insight and conclusion after insight and conclusion that set new directions for future thought.

Synthesis, creative churn, new explosion.

Looks a bit like the “oscillating universe”. Cool analogy. Still needs a creator.

Consider Aquinas. The closest thing to a logic-based approach to universal understanding since Aristotle, if lacking the huge empirical / natural philosophy component of his forerunner. The important thing is that within the parameters of his mentality, Thomas was also trying to synthesize and unify knowledge across the ontological spectrum.

For the bibliophiles, here’s the million and a half or so words of the Summa Theologica – his masterpiece – in a modern leather binding and a 1688 edition. Click for a hyperlinked translation of the whole thing.

The

magnitude of his effort seems unreal, and then you consider he was

working mainly from memory in an era without printed books or computers.

He took Aristotle-derived logic tools, encyclopedic vision, and

sci-fi-level memory feats to unify Aristotelian thought, centuries of

Arab commentary, and Christian revelation into a grand unified theory of

everything.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas, 1471, tempera on panel, Louvre, Paris

Thomas between Aristotle and Plato and above the great Arabic scholar Averroes, who he refuted.

Thomas between Aristotle and Plato and above the great Arabic scholar Averroes, who he refuted.

One column cites an Aquinas scholar on the Summa: “its structure attempts to express the structure of reality as a whole,” then follows up with the question: “What kind of mind tries to do that?” Our answer is an epochal one.

Aquinas’ failure to reason his way to the incarnation is strong confirmation of our ontological hierarchy, where the nature of ultimate reality is outside the reach of observation or logic. It doesn’t escape our notice that this is the same conclusion reached by Aristotle. Ultimate reality is logically necessary but is beyond characterization qua itself. Thomas identified faith as the epistemological mode needed to access that lofty space, and the Band has yet to see an argument to the contrary. A lot of post-Enlightenment lying and hand-waving, but no argument.

As an epochal mind, Thomas also represents herculean synthesis of the current state of knowledge, creative manipulation of this material, and the defining roadmap for the following era. His methods and breadth personify late medieval intellectual culture.

Note how in their own terms these figures perceive that ontology is hierarchically stratified, that different epistemological tools are needed, but that it’s also all connected through causal necessity. They are less systematic than the Band but they are also vastly more intelligent than we are. What for us requires the artificial structure of a schematic is likely intuitive natural existence for them. It’s obvious to them in ways that are not accessible to the rest of us.

Il-Grande-Iulio, Dante's Cosmology

The conception of the universe that we see in Dante is Thomistic. Patterns associated with him were dominant until the rise of Renaissance humanism. This - and his subsequent association with this period of intellectual history - makes him epochal.

Now let's jump over Leonardo to Newton – the paradigm of the Scientific Revolution and a genius so epochal that he personified both Enlightenment rationalism and the empirical Scientific Method.

The conception of the universe that we see in Dante is Thomistic. Patterns associated with him were dominant until the rise of Renaissance humanism. This - and his subsequent association with this period of intellectual history - makes him epochal.

Now let's jump over Leonardo to Newton – the paradigm of the Scientific Revolution and a genius so epochal that he personified both Enlightenment rationalism and the empirical Scientific Method.

Jean-Leon Huens-National Geographic Stock image

With Aristotle, a claimant of the title smartest man who ever lived.

At that level, it’s a pick ‘em.

The fading dream that we could quantify our way to ontology is a consequence of his unearthly ability to describe material reality mathematically. All the ill-placed certainty and absurd secular transcendence connected to the Modern cult of Science!-worship is part of the legacy. Newton made math a veil that these frauds could use to pretend they were meaningfully different from conventional shamans.

Math is refined symbolic logic, so it has an internal truth-value that belongs to the abstract level of ontology rather than the material. It’s more perfectly true than empirical observation in terms of reproducibility, precision, and certainty. But math is a system of operations derived from quantified descriptions. Like simplified classical geometry it can point towards the absolute, but can’t access it’s essential nature. That’s the leap of faith, remember?

With Aristotle, a claimant of the title smartest man who ever lived.

At that level, it’s a pick ‘em.

The fading dream that we could quantify our way to ontology is a consequence of his unearthly ability to describe material reality mathematically. All the ill-placed certainty and absurd secular transcendence connected to the Modern cult of Science!-worship is part of the legacy. Newton made math a veil that these frauds could use to pretend they were meaningfully different from conventional shamans.

Math is refined symbolic logic, so it has an internal truth-value that belongs to the abstract level of ontology rather than the material. It’s more perfectly true than empirical observation in terms of reproducibility, precision, and certainty. But math is a system of operations derived from quantified descriptions. Like simplified classical geometry it can point towards the absolute, but can’t access it’s essential nature. That’s the leap of faith, remember?

Newton's sketch of the structure of the Philosopher's Stone - the alchemist's Holy Grail - and a graphic version from an alchemical site.

If you take the entirety of Newton's vision, you can see he was trying to quantify his way across the gulf. His obsession with Biblical numerology is uncomfortable for secular transcendentalists - but who cares. He was trying to connect man and the world to God through the logical operations of his vast intellect. And his numeric logic fell just as short as St. Thomas’ written form before him.

If you take the entirety of Newton's vision, you can see he was trying to quantify his way across the gulf. His obsession with Biblical numerology is uncomfortable for secular transcendentalists - but who cares. He was trying to connect man and the world to God through the logical operations of his vast intellect. And his numeric logic fell just as short as St. Thomas’ written form before him.

But in failing that impossible quest, he describing material logos – the divine logic behind the entropic, blurry appearance of the fallen world – so effectively that he set the course of history.

Here's where narratives warp history. Newton the magus is a different conception of him than the apple-on-the-head physicist. The latter is the secular transcendent fake Flatland version - Newton as secular materialist - and it appeals to today's hollow and demoralized populace. It also presents a false impression of him based on what we actually already know. But Newton the magus sells him short too. He's that epochal. He wrote considerably more on theology than science. Together, it looks like a massive attempt to convey the full graduated ontological unity of reality that was ultimately beyond even him. If you want to traffic in reality and accept Newton as an intellectual authority, then that means the whole Newton. Click for an interesting look at Newton’s esoteric fundamentalist Christianity and occult interests.

Here's where narratives warp history. Newton the magus is a different conception of him than the apple-on-the-head physicist. The latter is the secular transcendent fake Flatland version - Newton as secular materialist - and it appeals to today's hollow and demoralized populace. It also presents a false impression of him based on what we actually already know. But Newton the magus sells him short too. He's that epochal. He wrote considerably more on theology than science. Together, it looks like a massive attempt to convey the full graduated ontological unity of reality that was ultimately beyond even him. If you want to traffic in reality and accept Newton as an intellectual authority, then that means the whole Newton. Click for an interesting look at Newton’s esoteric fundamentalist Christianity and occult interests.

Michael Rysbrack and William Kent, Newton's monument, 1730, Westminster Abbey

Newton's tomb was designed by another old friend - architect William Kent with sculpture by Flemish artist Rysbrac who worked in England. The sarcophagus relief depicts his work with math and optics and as Master of the Mint. The books next to him are Divinity, Chronology, Opticks and the Principia.Above him a pyramid symbol of eternity points to a celestial globe and Urania, muse of Astronomy.

The decorative arch was added in 1834 and actually makes the whole thing less of a blasphemous deification of a human and more like the shape of Newton's real thought.

Newton's tomb was designed by another old friend - architect William Kent with sculpture by Flemish artist Rysbrac who worked in England. The sarcophagus relief depicts his work with math and optics and as Master of the Mint. The books next to him are Divinity, Chronology, Opticks and the Principia.Above him a pyramid symbol of eternity points to a celestial globe and Urania, muse of Astronomy.

The decorative arch was added in 1834 and actually makes the whole thing less of a blasphemous deification of a human and more like the shape of Newton's real thought.

The most incredible thing about Newton is that the scientific mind he is known for was only one facet of his intellectual scope. Consider our Hermeticism occult posts. Remember the jumble of different ideas swirling around - alchemy, theology, Biblical and other numerology, natural magic, quantitative science, sacred geometry and how they flowed together? Add economics, numismatics, and whatever else and you have Newton’s base.

Take the observation that this level of genius intuitively grasps the multidimensional nature of ontological-epistemology that comparative half-wits like the Band need to puzzle over and carefully chart. Newton is using his unearthly intelligence to marshal his entire intellectual tradition, generate new insights, and create new eras.

Take the observation that this level of genius intuitively grasps the multidimensional nature of ontological-epistemology that comparative half-wits like the Band need to puzzle over and carefully chart. Newton is using his unearthly intelligence to marshal his entire intellectual tradition, generate new insights, and create new eras.

There's a pattern, isn't there. We don't have to be able to fully understand them to see their traces.

All perceive a different ontological levels expressing a more profound unity beyond them. All fail to make encyclopedic synthesis and logic reveal the nature of this unity. Aristotle leaves it blank. St. Thomas and Newton were Christians, so their failure confirms the necessity of faith as the epistemology of ultimate reality. Which is nice.

As epochal minds, they keep reorienting logically towards higher unities with insights that define their ages. One epoch gives way to the next, but there's a gap between Thomistic and Newtonian realities. When you look beyond base materialism to the vertical fulleness of ontology, you see that Leonardo is the missing link.

As epochal minds, they keep reorienting logically towards higher unities with insights that define their ages. One epoch gives way to the next, but there's a gap between Thomistic and Newtonian realities. When you look beyond base materialism to the vertical fulleness of ontology, you see that Leonardo is the missing link.

The problem with Leonardo is that he’s the secretive one. He is famous – an international household name – but most can’t really tell you why. Some weird machines we’re told couldn’t really work, unusual drawings, the Mona Lisa…

Most of his insights were private and so fell outside the historical mainstream. He didn’t belong to any school of thought or movement and had no fixed methodology beyond observing, thinking, and describing.

Most of his insights were private and so fell outside the historical mainstream. He didn’t belong to any school of thought or movement and had no fixed methodology beyond observing, thinking, and describing.

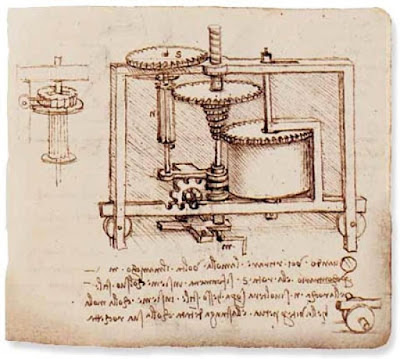

Studies of Toothed Gears and Hygrometer

Because he worked individually many of Leonardo's inventions were curiosities that he dodn't share. Like inventing the exploded drawing to show how something works in a single image.

Drawing was how Leonardo explored the world. Makes sense he'd refine its abilities to communicate.

His engineering ideas didn’t feed into the borning Scientific Revolution. Although they should have. Like conceptualizing the basic principles of a variable speed transmission. In the 1400s.

Because he worked individually many of Leonardo's inventions were curiosities that he dodn't share. Like inventing the exploded drawing to show how something works in a single image.

Drawing was how Leonardo explored the world. Makes sense he'd refine its abilities to communicate.

His engineering ideas didn’t feed into the borning Scientific Revolution. Although they should have. Like conceptualizing the basic principles of a variable speed transmission. In the 1400s.

Leonardo would record his observations and inventions in his sprawling notebooks with meticulous drawings. This meant that people didn't know about them and the ideas were never developed.

His anatomical studies were just as out of time. Dissection had been common in the Middle Ages, but Leonardo's systematic approach, meticulous skill, and comparison with living people gave his drawings unprecedented accuracy.

Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the shoulder and arm and the bones of the foot, 1510-1511

This is is good look at his anatomy. Consider that he was producing these drawings with no reliable studies to follow and with no modern equipment. Had it been publicized, this work would have greatly advanced the understanding of the body.

This is is good look at his anatomy. Consider that he was producing these drawings with no reliable studies to follow and with no modern equipment. Had it been publicized, this work would have greatly advanced the understanding of the body.

Leonardo's interest in the natural world went way way beyond the human body in every possible direction. We can't sum it up, but here are some selections to give a sense of the breadth and the use of drawing to understand.

Leonardo on nature:

Leonardo on nature:

From common patterns in water movements and bnotanicals, to animals of all kinds, to perhaps the first pure landscape in Italy.

As an engineer, Leonardo was constantly devising new things - some worked, most were just concepts, but the variety is staggering. Here are tow opposites - ideas for a rapid-fire crossbow and Archimedes Screws and Water Wheels for power generation.

As an engineer, Leonardo was constantly devising new things - some worked, most were just concepts, but the variety is staggering. Here are tow opposites - ideas for a rapid-fire crossbow and Archimedes Screws and Water Wheels for power generation.

Because he saw everything as connected, Leonardo's thoughts in one area reflected onto all the others. The study of nature improved his art. But he also treated art as a topic in itself - his treatise on painting anticipated the major art issues of the next couple of centuries, but was never never published or widely circulated.

Leonardo Da Vinci, Head of Leda, around 1504-1506, pen and ink over black chalk, Royal Collection

Leonardo was typical of Florentine artists for his use of preparatory drawings for planning pictures. This was probably for a unpainted mythological scene of Leda and the Swan. Animal rape seems to have always been popular among the elites. Technically, note how effectively Leonardo's mastery of drawing crosses over into more artistic subjects.

It is all connected. The flow of the hair follows the same natural patterns that Leonardo saw in wind and water.

Leonardo was typical of Florentine artists for his use of preparatory drawings for planning pictures. This was probably for a unpainted mythological scene of Leda and the Swan. Animal rape seems to have always been popular among the elites. Technically, note how effectively Leonardo's mastery of drawing crosses over into more artistic subjects.

It is all connected. The flow of the hair follows the same natural patterns that Leonardo saw in wind and water.

As an artist he was unproductive - painting painfully few works with many of those unfinished. But he managed to create three of the most famous images of all time – the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, and the Vitruvian Man.

His art career began with an apprenticeship to Andrea del Verrocchio – the preeminent sculptor in Florence and one of the main art workshops of the later 15th century. There are numerous accounts of Leonardo's absurd gifts – his singing voice, beautiful looks, freakish strength, and persuasive rhetoric. Yet he was in no hurry to leave, and stayed on longer than lead apprentices in a prestige shop would normally have.

Verrocchio, Equestrian Statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, 1480–1488, Venice