If you are new to the Band, occult imagery posts are shorter looks at the background and patterns in occult images. For more posts on occult symbolism, click here. For an introduction to the Band and the Dismantling Postmodernism series, click the featured post to the right or check out the archive.

This post is a bit off-beat. Why look at occult aspects in 1960s Marvel Comics? Think about the degraded state of the world around us - most of us have asked at some point how evil gained such a hold so quickly. The first answer is that is has always been there, but has grown more open. But this just raises the question of why it has it become so open, and there is no single answer to that one. One factor has to be the disappearance of any clear moral or religious principles in popular culture - it is demoralized, in the sense that moral standards have been removed. The idea that all our mass culture is purely materialist has become so ingrained that it seems weird to even think about. But the media world that we are bombarded with continuously is morally ungrounded, relativistic, and ruled by will and desire. Given that we have always used stories as exempla - guides for moral behavior - this is not ideal. It is much easier to deny reality in practice when our popular mythology excludes any meaningful notion of a moral foundation. Consider Marvel as an example. Once you see this pattern, you'll notice it everywhere.

Today, when people think Marvel, they tend to think of the movies. Not surprising, since the movies have been enormously successful. But the movies derive from the comic universe that first took form in the 1960 - this is where the moral relativism needed to find a genocidal super-villan empathetic begins. Because at its core, the Marvel Universe is essentially Luciferian, ruled by will and power, and with no grounding in moral or spiritual principles.

Let's look closer. This post will introduce the foundation of an amoral esoteric universe. The next will tackle the appearance of the full-blown occult. But first we have to clarify some terms.

One of the problems encountered when looking into occult themes is defining the terms. The Band uses occult to refer to activities intended to contact or control supernatural forces, especially ones connected with supernatural entities like demons or spirits. Esoteric covers all the "un-scientific" bodies of metaphysical lore, much of which isn't literally occult. They overlap in places - magic is one place, and divination and astrology come really close. It's fuzzy.

The Occult World of Doctor Strange, Marvel Comics Calendar, 1980

Both fall under the Satanic inversion umbrella by putting one's will or desire over the order of reality - logos to use the Biblical Greek word. Becoming one's own god, or doing what thou wilt. And they are insidious, because while they are based in notions of the supernatural, they operate on the in-between spaces of existence - literally above the natural or material reality, but below the level of ultimate reality/God/the first cause.

This means you can claim "atheism" while still doing esoteric, occult-seeming things.

On one hand they claim not to believe in the supernatural. On the other, they describe supernatural activities. Is this occult? Esoteric? The answer is a conditional yes to both, but does it really matter what we call it?

The pattern is one we've seen with automatic writing - rejecting the concept of the "supernatural" but keeping supernatural things by making up words.

In effect, we are talking about super-powers. So what we have are two different concepts of supernatural - of what it means to be "above" nature.

From a philosophical or religious perspective, this means more or less "real" in what philosophers call an ontological sense.

Ultimate reality - God in Christian metaphysics - is the fundamental basis of all that can or can't exist and is at the top of this picture. Empirical knowledge of this is impossible because it is literally beyond the limited purview of our material existence.

Our world is in the front, projected through the higher planes in-between.

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965, MOMA, New York

Higher levels of reality - ontological levels - are more real in the way a thing is more real than a photo. Kosuth captures this idea by contrasting a chair, the picture of the chair, and the definition of "chair". The higher planes are to the chair as the chair is to the picture and definition.

,

There is no way to cross to a higher plane physically. They are literally external to material reality. Their nature and their existence is knowable only through faith. Even miracles align with this because miracles are given, not gained. Divine action is not compelled in the manner of casting a spell.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, circa 1563, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

No matter how far you go, how small you get, or how many dimensions or timelines you conjure, you aren't getting to heaven.

The atheist-occult or official satanic perspective is different. This notion of supernatural refers to things that are immaterial or outside "scientific" validation, but are connected to material reality. The quote up above is a perfect example from this.

John Northern Hilliard, Greater Magic, Kaufman and Company, Washington DC, 1938, 1994

From the blurb: "Considered by most magicians-both professional and amateur as the “bible” of magic."

Magic and telepathy are invisible natural forces, extra dimensions are mathematical abstractions, and alternative timelines assume the same comprehensible physics. You're not at the level of ultimate reality or God, but you're outside the material world, and you can get there from here.

The philosophical/religious and occult/esoteric reflect incompatible world views. They do both see "reality" as larger than the material existence we live in, but beyond that they are opposite.

Hildegard of Bingen has a vision, detail from her Liber Scivias, 1142–1151; copy 1927-1933, State Library, Wiesbaden

One accepts the limits of our observation and understanding and uses logic to conclude that there has to be a fundamental substructure to what we see. By nature this can't be known through direct empirical experience, but this absence is what lets us recognize human limitations. Which guides us to accept reality and seek the truth.

In short, the mix of logic, empiricism, and faith reveals logos.

The other rejects reality for desire.

From this perspective, the supernatural is connected to material reality in ways that are comprehensible or accessible. This is a big tent. Speculative physics is essentially the descendant of esoteric numerology when it tries to explain ontology with materially impossible dimensions and conditions. The occult in any form clearly fits. This has serious implications for pop culture.

The most popular genres of speculative escapist fiction - fantasy and science fiction - come from opposite directions, but they both have purchase on the second "occult" form of supernatural.

Jack Kirby, the "Negative Zone", Fantastic Four # 51, p. 18, script by Stan Lee, inked by Joe Sinnott, June 1966

One of the collages Marvel creative force Jack Kirby liked to use for cosmic scenes. The idea was borrowed from the contemporary Pop Art movement, just as Pop artists borrowed imagery from comics. Here, Mr. Fantastic uses supernatural "science" to access another dimension. The science is the idea of an anti-matter analog to our reality. The fiction is that you could build a machine to go there.

Steve Ditko, Strange Tales # 116, p. 23, script by Stan Lee, January, 1964

Thor crosses dimensions with a blend of magic and mythology, the ingredients of fantasy.

But the result of the occult supernatural is the same as supernatural science - not only can you imagine other dimensions in our terms, there are different ways to get there.

Once we see the difference between the philosophical/religious and atheist/occult versions of the supernatural, the patterns become clear. Mainstream escapism, whether "fantasy" or "sci fi" has relentlessly pushed the second with multiverses and magic that are accessible and/or manipulable by us. This literally normalizes - as in makes the norm - a Luciferian world view where humans can wield extraordinary powers, but logically-consistent spiritually is absent and humanity itself an insignificant speck in a terrifying, endless multiverse. What is the basis of morality in this world?

Steve Ditko and Stan Lee, closing panels of Marvel's Amazing Fantasy # 15, August, 1962.

The first appearance of Spider-Man and an early form of his famous line "with great power comes great responsibility".

Responsibility to who?

Peter Parker is upset because his selfishness was indirectly responsible for the loss of his uncle. The idea is that someone has a share of accountability for things they could prevent, but it is just assumed that the distinction between right and wrong is obvious.

Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, panels from Fantastic Four #1, November, 1961, Marvel Comics.

Secular moral purpose is so obvious that early 60s Marvel's flagship presented it as self-evident. Where this goes off the rails is in what is meant by "help mankind".

In 1962, public morality still reflected traditional American Christian values - values from outside the imaginary universe that readers would bring to it. In other words, morality is assumed. But assumed moralities have no foundations and are easily degraded or replaced.

We see this in comics today, where "responsibility" has morphed into serving a globalist monoculture.

You might even call it... the prime directive.

The lesson, as always:

Which brings us to Marvel.

It is easy to forget in the era of the MCU that comics weren't always as fringe as they are now.

Comic book spinner rack in 1956.

When Marvel came into prominence in the 1960s, comics were primarily disposable youth entertainment. Children bought 10 then 12 cent comics from any number of venues - drug and department stores, newsstands, convenience-type stores, etc. - before moving on to other interests.

There were no specialized comic shops, and the older youth/adult reader was largely a creation of Marvel's new approach. Even as the age range of comic readers gradually widened through the 60s, it was still much narrower then today's widely dispursed fan base. This meant that the impact on the consuming demographic was much more concentrated, all else being equal. Today's market is niche, driven by collectors of widely ranging ages. There isn't much turn-over in the audience from year to year. In the early 60's, the readers were clustered in the adolescent and pre-adolescent years. Children had aged out of comics pretty quickly - some publishers just reprinted the same cycle of stories, knowing that the current readers wouldn't know them. There was vastly more penetration into the demographic consciousness.

And all else wasn't equal. Some sales figures from an interesting website that discusses early Marvel in an thoughtful way. His contention that the Fantastic Four was the "Great American Novel" is an entertaining read.

Marvel started reporting sales data in 1966, and the numbers confirm that the company's top performers were The Amazing Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, and The Mighty Thor, with the former two selling north of a third of a million units per month. This to a far narrower audience in a less populous country than today. Comics were collected and shared among groups of friends, extending their reach. In terms of exposure across a largely adolescent demographic, comics were a completely different animal than today.

And some sales data from a recent month for comparison. Keep in mind these are estimates based on units shipped to comic shops. It doesn't account for the long discount boxes of unsold copies.

We have the Avengers, buoyed by the movies as the top performer with almost a quarter of 1969 Spider-Man. Spidey himself lands about 80 percent of that with a special edition, while his flagship - the only one of the above three present - is a shadow of its former self.

There is no comparison between the significance of comic books on the youth zeitgeist between now and then. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is a better comparison, but it's way broader in appeal and massively promoted in every possible channel. Comics were a kid thing - disposable trash to grown-ups, but a parallel universe - a contemporary mythology - for young readers.

Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, lower panels from page 2 of Journey into Mystery # 112, January, 1965, Marvel Comics.

Thor tells some young fans about his fight with the Hulk. This is a window into an fantastical world designed to appeal to a youthful imagination.

This is what established the Marvel brand deeply enough in collective unconscious to enable the launch of the movie version of their universe. The 60s foundation, expanded over the next couple of decades, is the foundation of the MCU - an entertainment juggernaut that brought the Marvel mythology into the cultural mainstream. Young people who would have read a comic in the 60s helped put an Avengers movie over two billion dollars in the 10s, only now its isn't just adolescents any more. It's worth looking at Marvel because they've been writing our mythology for a while.

The question is: what sort of world did their youthful mythology create?

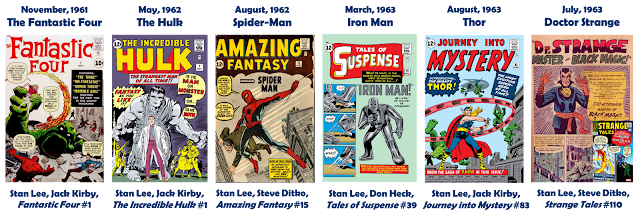

The basic history of the "Marvel Age" is well known. Beginning with the Fantastic Four in 1961, Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and other creators unleashed a string of titles that redefined the superhero genre. It was an impressive run:

The concept was built around heroes with human personalities set in the same world as ours. The world outside your window, so to speak. But this was misleading, and not just for the fake super powers. It was early 1960's America, and religion was nowhere to be seen - spiritual lives of any kind, for that matter.

When it comes to Marvel metaphysics, the cornerstones were laid in two of Marvel's early flagships - Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four and Thor - and another early hit - Steve Ditko and Lee's Dr. Strange. These took a while to get going. The early origin stories were threadbare things - a quick summary story to establish the powers so the adventures can get started. The simple coolness of superheroes was enough to enthrall the young early 60's audience. But one of Lee's marketing successes - and Lee was an excellent huckster among other things - was targeting university aged and older readers. Older readers needed more internal coherence, and the steadily expanding shared universe that Marvel gave them is the direct ancestor of the MCU today.

Steve Ditko, cover to Amazing Spider-Man #1, March, 1963, scripted by Stan Lee, Marvel Comics

Amazing Fantasy # 15 was the final issue of the title, but response to Spider-Man was such that Marvel gave him his own title within a year. Second appearance and we already have a cross-over with the FF, who by now were established as a major hit.

One of the things that made Marvel appealing was the idea of a shared universe. Characters could cross over and villains could face different heroes. This is still popular - consider the success of the Avengers movies. Over time, this built up an impossible continuity, but during the 60s, this world was just being laid out, And the form it took was essentially the Luciferian vision promoted in all the pop sci-fi and fantasy of that era.

We do have to consider the issue of authorship. Most comic fans agree that Kirby was shafted by Marvel while Lee was the ultimate company man. But Kirby also seems to have been the primary creative force on his titles due to a process called the Marvel method. This had the artist storyboard a short plot description, then the writer filled in the words. Lee's plotting on Kirby's titles - the FF and Thor - was minimal. To be fair, Lee's dialog is underrated. He had a cornball style that could be cringeworthy, but gave his characters clear voices and memorable if flat personalities. The cheesy exclamations and catch phrases like "it's clobberin' tme" or "flame on" are awesome to the unself-conscious child. But Kirby transformed the simple origins into far-out journeys through time and space.Click for a good look at the history.

Jack Kirby, cover to Fantastic Four #60, March, 1967, Marvel Comics

The Fantastic Four started with a simple but original premise - the heroes have personal connections before gaining powers. Reed and Sue are a couple, Johnny is Sue's younger brother, and Ben is Reed's best friend and like a brother to the other two. This introduced simple family dynamics into the stories and made the characters more relatable. Spider-Man perfected the ordinary guy hero, but the FF were the test run.

Kirby's style was bold and dynamic - not exactly realistic, but ideal for superheroic action.

Jack Kirby, cover to Fantastic Four Annual #6, November, 1968, Marvel Comic

Kirby transformed the "scientist and his girlfriend with his friend and her brother" into a wild, fantasy-science string of adventures through time, space, and other dimensions.

But there is no spirituality of any sort. Whether moving faster than light, shrinking to sub-atomic size, or crossing into the "Negative Zone" like in this annual, the other worlds are all reachable from ours. They are not higher planes in the religious or philosophical sense.

Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott, Fantastic Four #60, p. 16 March, 1967, Marvel Comics

The values were generically "heroic" in a mid-20th century implied American Christian sense. Here we see the Thing battling against an essentially unbeatable enemy with typical persistence. He was somewhat tragically trapped in a monstrous form, and unlike today's "heroes" was defined by courage and determination. But as mentioned above, this morality is not grounded in any higher metaphysical principles. It is a pure triumph of will over cosmic forces.

Stirring if we assume or project American Christian values, but essentially Luciferian in structure.

One of the ways that self-centered satanic globalism undermined society was to mock traditional Christian values as staid or uncool. A plot where the Thing battles back against a cosmic powered Dr. Doom because of the purity of his heart or nobility of purpose would have been disqualified as cheesy. So what makes him virtuous is best described as the triumph of his will. But pure will is not a virtue in itself. What is he fighting for?

A generic notion of "freedom". Dr. Doom is looking to establish totalitarian rule over the planet. The FF oppose him as defenders of the idealized freedom propaganda that the American political and economic elites doubled down on during the Cold War - this is 1967. But we know that this rhetoric doesn't fit the reality of Deep States, centralized media, and globalist finance. The best case is that they are fighting in self-defense - Doom attacked with massive force and they repelled him. But in any case, the motivation is material. It is of this world.

Defending country or self is justifiable, but it is relative.

From the atheist-occult perspective, there are no higher realities in the philosophical-religious sense. Everything is based in our claims about our material existence. There can be no grounding of principles in moral absolutes because there are no absolutes to ground them. Freedom itself is the principle - it is a necessary condition to do what thou wilt - and the triumph of the will is what makes it possible.

Or, as Stan and Jack put it:

Jack Kirby, panel from Fantastic Four #50, inked by Joe Sinnott, scripted by Stan Lee, May 1966, Marvel Comics

Power places you above morality in the Marvel Universe. Galactus is a "higher" being, though he exists materially in our world, and cannot be judged because he's strong.

If the phrasing seems familiar, it's close to the title of Nietzsche's famous Beyond Good and Evil. The message is similar as well - in Nietzsche's syphilitic ravings, good and evil are based on a Christian "herd" or slave mentality. The true moral distinction ought to be between good and bad, since this is based on the value to the self in realizing the will to power. This is the same system of amoral Luciferian solipsism preached by lunatic charlatan and globalist shill Jordan Peterson.

From the philosophical-religious view, moral principles supersede unchecked individual desire. Freedom isn't the end in itself, but what you do with the freedom.

The comic blurs things by making Doom evil in a traditional moral sense as well, so that fighting him is also virtuous. But this is implied American Christian morality. It relies on a collective sense of moral principles to imply notions of good and evil in what is literally a power struggle. Implied notions lack staying power. Without an anchor, power struggles can be framed to reflect whatever set of values the creators want.

Without an anchor, even a seeming cut and dry fight like the Thing's is open to relativistic questions like 'would Doom be wrong if in taking over country X he saved millions of lives that would be lost?' This is the spiral we are on today - where "ethics" are politicized and any action can be defended or condemned with the right relative case.

Thor began as an attempt to create a "Superman" type without seeming derivative - the simple origin tells of a lame doctor who finds a magic stick that turns him into a version of the Norse thunder god Thor. "Version" because Lee's version bore no resemblance to the source material other than the name and idea of a "thunder god".

Jack Kirby, cover to Journey into Mystery #85, October, 1962, Marvel Comics

There was nothing Viking about Thor beyond the name. His heroic motivations are basically the same as the Thing's - an implied Christian American morality without a hint of its spiritual foundation. Only he was given a nobler demeanor - sort of an Errol Flynn movie notion of chivalrous honor.

In his third appearance, Thor's nemesis was introduced. Loki also took his name and concept from Norse myth, but is a completely new creation.

Jack Kirby, cover to Thor, #151, April, 1968, Marvel Comics

Journey into Mystery was retitled The Mighty Thor with #126.

The series took off when Kirby realized Thor didn't really fit an earthly setting and took him off-world. The evolution in the character, and in Kirby's style, is obvious in the cover comparison. Thor's design has the force and vigor appropriate to a cosmic powerhouse and the poses scream action, although the design would be impossible to imagine in live action.

Jack Kirby, Thor #159, p. 3, inked by Vince Colletta, scripted by Stan Lee, December, 1968, Marvel Comics

Kirby's Asgard transformed the home of the Norse gods in mythology into a gleaming fantasy city in far-out dimension. Don't forget that psychedelia was in the air, and Kirby was taken with counterculture imagery.

The "gods" turn out to be a race of extradimensional superhumans rather than spiritual beings in the philosophical-religious sense of the word. Asgard is no different from the Fantastic Four's Negative Zone ontologically. They are both outside material reality - supernatural - but accessible to it.

.

Jack Kirby, cover to Fantastic Four #73, April, 1968, Marvel Comics

They could even fight! That's the marketing beauty of new popular characters in a shared universe.

But it means that they all live in the same universe!

Then we have the foray into the actual occult with Steve Ditko and Stan Lee's Dr. Strange, a hero with magic as a power. This title was not as popular as the other two, but was important in fleshing out Marvel metaphysics. Like Thor and the FF, Dr. Strange was introduced with a brief, pulpy origin that was developed into a fantastical imaginary world.

Steve Ditko, Strange Tales #116, p. 22, scripted by Stan Lee, January, 1964, Marvel Comics

From the beginning, Strange was crossing dimensional borders by magic and encountering various arcane creatures like Nightmare, lord of the Dream Dimension. Nightmare was a recurring enemy.

Steve Ditko, cover to Strange Tales #146, July, 1966, Marvel Comics

Eventually he meets Eternity, the personification of space, and the first of Marvel's abstract embodiments of cosmic "principles". Now we have crossed into a form of pantheism - the idea that the universe is alive and sentient.

We've already noted the shared universe. The supernatural science of the Fantastic Four, the mythical fantasy of Thor and the magic of Dr. Strange all coexist. The explanation is that their other dimensions are metaphysically more or less the same - just interchangeable ways of crossing over. Whatever you call it, it's all horizontal - none of these dimensions are "higher" in a spiritual or metaphysical sense.

Jack Kirby, cover to Strange Tales #123, August, 1964

They can even fight!

Over the course of the 60s, Marvel unspooled a fantastic universe with new form of bold clean comic storytelling that still resonates today. But metaphysically, it was a universe without any kind of moral compass beyond vague civic nationalism. Certainly there is no presence of a spiritual concept of virtue. On the contrary, the most powerful creature Kirby introduced during his run is Beyond Good and Evil. The supernatural is accessible, humans access enormous, even cosmic, powers, universal forces are sentient, morality is contemporary soft leftism, and anything spiritually higher is conspicuously absent.

A truth-seeker might ask, what sort of society has this as an unofficial mythology?

Click for part 2

Click for part 3

No comments:

Post a Comment