If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right.

Leon Battista Alberti, title page to De re aedificatoria, Strasbourg: M. Iacobus Cammerlander Moguntinus, 1541

Alberti’s treatise on architecture was written by the eminent humanist around 1450, and as the first work of its kind since antiquity, it is one of the most influential texts in the history of the field. In it, he turns to ancient sources to formulate a theory of design. This is the forerunner of countless such works, each offering an original spin on timeless principles.

Before returning to the roots of architecture, it is necessary to clarify some basic principles. One of the more irritating features of architectural theory is the rather loose usage of critical terminology in what appears to be an effort to make “tradition” say whatever you want. There is a fundamental split between architecture as written theory and as actual practice; even Alberti built his theory of “ancient” architecture from primarily textual rather than visual sources. Let’s put aside appeals to first principles for the moment and take a look at the development of architecture from the perspective of cultural history.

Two of the most common, and loosely defined, terms in architectural theory are form and function. These deceptively simple words mask a host of meetings that theorists will pick and choose from to justify whatever agenda they are pushing. Form refers to the building as a physical object; what it looks like as well as what it is on a more essential level. But this raises complications, because

Modernists tend to think of form as the purified philosophical essence, intrinsically connected to the structure of the building, independent of any ornament, and governed by simple geometries. This is basically Platonic in that it regards surface decoration as mere superficial appearance that distracts the enlightened mind from the intellectual joy of contemplating pure Form. But the reality is that ornamentation has always belonged to the formal aspect of architecture, and that even the most rigorous classicists never imagined doing away with aesthetically pleasing structures.The Modern emphasis of formal simplicity is not a "purification", but a distortion and perversion of something as old as civilization.

Egerton Swartwout, Monument to American soldiers, dedicated 1937, Montsec, France

In the weird, simplified Neoplatonism of the Modernists, architectural “beauty” was supposed to reflect the intellectualized ecstasy of Plotinus, mystical contemplation of pure abstract unity. The reality was a mix of inhuman polyhedral and badly-aging concrete blobs. How did this happen?

The first issue is one that the pompous frauds that litter the art world flee from as if it was aesthetic credibility: Modernists are atrocious philosophers. The basic point of Platonic formal perfection is that it can’t exist in the material world. It can only be experienced intellectually. Historically, the Forms have been represented by simple geometries, like Swartwout's Doric monument above, but these are precisely not the Forms. In classical architecture, as in Neoplatonic thought, simplified forms or geometries are the substructure of human experience, not the sum total of it. Decoration is then tastefully and harmoniously applied to appeal to the viewer and to bridge the gap between human subjectivities and the transcendence of the Forms.

Medieval Square in Rothenburg, Genmany

Rem Koolhaas, Casa da Música, 1999-2005, Porto, Portugal

Architecture that develops organically with a community is human scaled, appealingly decorated, and comfortably functional. The more contemporary alternative?

Not so much.

But Koolhaus has been on magazine covers, and had an awesome name for an architect.

Alvaro Siza Vieira, Escuela de Arquitectura de Oporto, 1987-1994, Porto

Chapel of Santa Catarina, late 18th century, enlarged 1801, tiles by Eduardo Leite, 1929, Porto

Porto is a bit of a contemporary architectural hellscape, partly due to the influence of this fine institution. It also has some fine historical buildings to provide a humane alternative. Notice how contemporary architecture is always evocatively photographed, like a piece of abstract sculpture. That is because it is conceived as such; cool (Kool?) to look at from afar, but an utter failure as the venue for human existence.

Poor Vieira lacks a Kool architectural name, and his building is aging badly. There is a different kind of symbolism in watching expressions of the pure essence of form slowly molder.

So what is the "essence" of a building? The short answer is that there isn't one, objectively speaking. What we have are subjective artistic impressions that sink or swim on the basis of their appeal. When Modernists assert "truth to materials", they are lying, since materials are inanimate and aesthetic decisions by definition arbitrary. Their "vision" advanced because they took control of key nodes in a centralized, institutional "elite" culture and forced their monstrous creations on an unwilling populace. As with any theory-spewing liar, Modernists require obfuscation and confusion - squid ink, so to speak - to hide their intellectual bankruptcy.The best way to eviscerate them is to go back to the real basics of architecture as a mode of human expression and pinpoint where the corruption took hold.

Manuel Aires Mateus, House In Leiria, 2010, Leiria, Portugal

More Kool contemporary sculpture and land art.

In the most basic terms terms, we can think of architectural form and function as the organization and manipulation of masses and spaces. This includes both the physical appearance of the building (structurally and ornamentally) and the materials that it is made of.

The masses apportion the spaces according to the needs, tastes, and means of the occupant.

This point is deceptively simple, but critically important:

Architecture is the organization and

manipulation of masses and spaces...

manipulation of masses and spaces...

...therefore, architecture is by

nature artificial and arbitrary.

nature artificial and arbitrary.

Function

We can also think of function in several ways.

Practical:

What is it to be used for? For example, you need big doors and pits or hoists in a garage.

Structural:

Colosseum, begun circa 70 AD, Rome.

The purpose of different elements in making the building stand. Is a wall load bearing? The arched vaults in the Colosseum give it a distinctive appearance but are also provide its structural integrity.

Symbolic:

Thomas Jefferson, Poplar Forest, beg. 1806, Forest, Virginia

What a building represents. This brings in decoration, which is communicative as well as ornamental. Jefferson's Palladianism - the octagonal shape and classical portico - symbolized reason and Enlightenment in easy to understand terms.

These functions are not always easy to untangle. Consider the Colosseum, with its famous perforated amphitheater form. A modernist would be quick to point out that this appearance reflects the structure of the building as a network of concrete groin vaults, the backbone of monumental Roman architecture. This configuration is also practically functional, providing the easy circulation and good light lines needed in a stadium, while providing the stable support that such a large building requires. So form follows function, but does it?

The Colosseum is slightly elliptical in shape, but there is nothing functional demanding this. It could have been slightly more elongated or a perfect circle; the precise shape is an arbitrary, subjective decision.

Wait. That means...

Form reflects function, but is not determined by it.

In other words, Modernist dogma reflects an enormous error in logic that is easily recognized empirically.

It is also an uncomfortable fact, an "inconvenient truth", if you will, that the Romans decorated the outsides of their buildings in ways that did not purely reflect structure. Each story of the Colosseum features one of the Greek orders: the Doric on the lowest level, the Ionic in the middle, and the Corinthian at the top. Greek architecture began as a structural system that evolved into a theory of ornament before being picked up by the Romans. But the Romans developed a much more technically advanced system of building that used concrete and fairly sophisticated vaulting to produce unprecedented buildings like the Colosseum. There is no need for load-bearing columns; their application here is purely ornamental.

The Colosseum was a very influential building, so we can contrast the difference between structural form and ornamental form by looking at later responses to it.

Giovanni Guerrini, Ernesto Bruno La Padula and Mario Romano, Square Colosseum (Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana), 1937, Rome

The Square Colosseum was classical in concept to the point of being anachronistic, so that it’s arcades are actually load-bearing stone vaults. This is a different material than the concrete Colosseum, but the structural logic of the form is the same.

Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai, 1446-1451, Florence, Italy

Alberti’s palace is vaulted in places, but overall is a planar arrangement of load-bearing walls and timber roof beams. Here, the arched windows and flattened orders recall the articulation of the Colosseum, but in a purely superficial way. In both cases, the reference to ancient Rome is symbolic, but in the Square Colosseum, it is also structural.

If we consider these from the viewer`s perspective, both buildings clearly serve their historicizing purposes. Alberti was a Renaissance humanist and wanted to base his designs on important ancient prototypes. Guerrini and company were attempting to realize Mussolini’s vision of reborn Roman glory. Why does it matter if the appearance reflects the structure?

It matters because the spinners of architectural theory require the fiction of an intellectual foundation to justify their deranged ramblings. Without illusory first principles to distinguish their art from mere vernacular, or "popular" building, all they have to offer are designs suited to a child's building blocks. But by imparting a magical determining power on form, these crude masses become expressions of an imaginary spirit or essence that somehow inheres in material shapes. Of course, no where in the purple prose of Modernist manifestos does a metaphysical justification or argument for appear. It is stated and taken on faith, and so belongs to that mind-numbingly stupid fallacy of secular transcendence, in which self-claimed materialists presume supernatural properties in physical objects.

How is the notion that there are magic essences in building materials exert control over the artist's creative process a positive step in human intellectual development? There are practices based on beliefs like this, but they aren't generally associated with philosophical or theological refinement.

Let's set aside the lies and ignorance and consider how architecture actually developed, in order to identify how something as fundamental as building things became so corrupted by narrow baseless theorizing.

Back to the Beginning

The history of architecture is the history of civilization. Early hunter gatherers constructed different kinds of shelters but with the invention of agriculture and the establishment of permanent settlements, more sophisticated buildings could develop. Prehistoric architecture was purpose driven, meeting needs for shelter and security, and dividing personal space into practical zones.

Çatalhöyük in modern Turkey was established around 9500 years ago and was continually inhabited for the better part of two millennia. It consisted of a network of dwellings with entrances and usable space on the roofs.

As civilization grew more complex, so too do the demands placed on the built environment. Stylistic consistencies develop over time around available materials and cultural tastes. History begins with the invention of writing, and the earliest known written language appeared in ancient Sumer, in Mesopotamia, around 5500 years ago. The Sumerians come by their "cradle of civilization" tagline honestly; they also are the first known to have used the sailboat, the wheel, and large-scale irrigation, while inventing the first recognizable cities in modern terms.

Sumerian Uruk is generally considered the first legitimate city, and is seen here in an artist’s recreation. Notice the specialized urban planning, with a wall, working port, organized roadways, and residential, commercial, administrative, and religious buildings. But the organization of space also functions on a deeper level, to express and normalize the values and of the civilization. This includes a symbolic dimension.

Notice how there is a central precinct separated from the rest of Uruk by a canal and a wall. This was the area reserved for the ruling elites of the city and access was strictly controlled. The most striking element is the ziggurat, a man-made mountain that towered over the cityscape and provided an elevated platform for the central temple of the city. This brought the temple closest to the heavens (practical) while creating a dominating, exclusionary zone in the middle of the city that physically demonstrated the importance of the priestly class. Priests ruled in ancient Sumer, and their status is normalized by becoming a physical fact of life for the residents. The rest of the central zone was occupied by palace complexes.

White Temple and Ziggurat, circa 3500-3000 BC, Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq).

As seen today, and in a recreation from an on-line video. In terms of form, the first thing we notice is it’s size, then its exclusively. The thing about architecture and urban planning is that they provide the context within which our personal and social identities are formed. We accept our “local” style as a baseline subconsciously, and internalize the hierarchies and distinctions baked into the physical realities of our daily lives. Of course the priests rule - they’re closest to the gods. They get to go up there!

We've gone back to the roots of architecture in search of the primal command to eliminate ornament or seek ontological certainty at the brickyard. And the Sumerians did use brick - the abundant, local, sun-baked mud brick, with scarcer wood timbers reserved for posts and rafters. Mud bricks weren't kiln-fired, and could be produced quickly and cheaply in standard sizes. They also lent themselves to heavy looking rectilinear forms that were effective at maintaining a cool interior in the blazing summer heat. The much newer adobe architecture of the American Southwest uses similar materials for similar purposes.

Tomb of Shulgi, circa 2000 BC

Corbel vaulting is a technique that brings rows of bricks or stones closer together until they eventually meet. The weight pressing down on the vault causes the two sides to lean together, locking the arrangement in place with tremendous stability.

E-dub-lal-mah, late 21st century BC, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), Iraq

The true arch appears at the same time, and represents a refinement on corbel vaulting. The pieces of an arch are cut as if they were segments of a ring, with each piece longer on the back curve than the front. When assembled across an opening, each brick is prevented from falling by the one next to it, with the result being a very strong structure.

The relationship between the form and materials of Sumerian architecture lets us take a closer look at the Modernist dogma of truth to materials. Sumerian and Babylonian vaulting were likely driven by the limits of their mud brick molding process, but there is nothing “essential” that dictates bricks have this precise form. Clay was also widely used for sculpture in the Bronze Age and after; how is such a violation of the inherent properties even thinkable?

Mud bricks from Tepe Sialk ziggurat, circa 3000-2900 BC, Kashan, Iran

Goddess suckling an Infant, Old Babylonian, circa 1900-1750 BC, 11 cm, private collection

Which reflects the true nature of clay? To pose the question reveals the absurdity.

All snark aside, the notion that the shape of an I-beam represents an ontological guidepost is truly moronic. Construction materials are driven by industrial production economies that have nothing to do with material "truth" beyond what is needed for manufacture. It is no secret that the enthusiasm for generic International Style towers is that a steel cage with standard windows is cheap to put up and maximized the space of the lot. Modernists love to wax on about the mechanical logic of the Industrial Age, but what does outsourcing artistic creativity to process engineering say about the value of the "creator"? Who wants to waste money on a design "expert" who can't think his way past foundry economics? Cue spiritualized mumblings...

Louis Kahn, Salk Institute for Biological Sciences, 1957-65, La Jolla, CA

“A great building must begin with the immeasurable, must go through measurable means when it is being designed, and in the end must be unmeasured.” – Louis Kahn

"You say to a brick, 'What do you want, brick?' And brick says to you, 'I like an arch.' And you say to brick, 'Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.' And then you say: 'What do you think of that, brick?' Brick says: 'I like an arch.'" – Louis Kahn

Kahn being immeasurable. I guess the lintel won the debate. But in all seriousness, consider the amount of self-deception that must go into venerating this lunatic. No wonder Modernists were so rabid in their ideology. The truth would be too painful to contemplate.

The first quote is included on an architecture school worksheet, but has no real connection to the exercises that follow. The only reason is to foster the impression of Kahn as some sort of guru who speaks self-evident wisdom.

Although it is easy to spoof, there is a serious problem here for Modernists. Consider this set of offerings from a steel company. How could an architect possibly decide which represents the “true nature of steel”, and, barring that revelation, how can they determine the shape of their design?

Back to the Beginning II: Egypt

Historical civilization developed in Egypt shortly after Mesopotamia, but the Egyptians built their most import structures in stone. The pyramid is the most famous feature of ancient Egyptian culture, and resembles a ziggurat as an artificial mountain. But the pyramids served as royal tombs, because the Egyptian pharaohs had managed to promote the belief that they were gods, or more accurately, became gods after death.

Giza Pyramids Complex, begun circa 2560 BC, near Cairo, Egypt

The size and distinct shape marks these ancient buildings as royal tombs.

But is there something inherent in a mound of rammed earth covered in a stone or brick shell? The first Egyptian pyramid was a step pyramid, the famous ones at Giza are prisms, and the ziggurat was a complex form with many sides. Let’s look ahead in time and further afield.

Left to right from top

Step Pyramid of Djoser, circa 27th century BC, Saqqara necropolis, near Memphis, Egypt

Great Ziggurat of Ur, 21st century BC, near Nasiriyah, Iraq

Temple I, Tikal, circa 732 AD, Guatemala

Pyramid of the Sun, circa 200 AD, Teotihuacan

Great Stupa of Sanchi, begun 3rd century BC, Madhya Pradesh, India

The pyramids of Teotihuacan are much flatter in proportion, while the Mayan version was much steeper and stepped. These served the same purpose as ziggurats of raising a temple. Ancient Buddhist stupas were semi-circular to represent the eternal cyclical nature of the cosmos. Apparently there is nothing inherent in earth that dictates what a structure must look like.

When you consider the effort needed to quarry and dress a granite block with bronze tools and stone files, we see how architecture reflects the priorities of a civilization, because anything built in stone must have been very important. Not surprisingly, the grandest Egyptian buildings after the pyramids are temples, huge stone homes for the gods on earth.

Luxor temple complex, begun late 14th century BC

Egyptian stone architecture was a post and lintel system, meaning that it it’s structure was based on horizontal elements or lintels resting on top of vertical supports or posts. Stone can bear tremendous weight but it is heavy and brittle, so the lintels must be thick and the the posts massive and closely spaced. This gives Egyptian architecture the characteristic sense of mass that so impressed the early Modernists.

That's not a typo. Le Corbusier claimed kinship with ruined monuments of the ancient world, including the Luxor temples.

Excerpts of genius (here is the rest in pdf form). Notice how there is no grounds for the proclamations, just the fantasy that weird declarations could have objective value.

Imagine you were a client. How you feel about hiring Le Corbusier after reading the pages reproduced above will reveal much about your cultural belonging and emotional health.

Though in some ways, we were fortunate to have the Corb. Otherwise, how would we know which of these is "not very beautiful"?

Even worse, we might confuse mere second-order geometries...

...with the true sublime power of holiness

We are all familiar with "The Emperor's New Clothes" and the desire not to appear ill-informed, but when we look at the absurd gulf between the claims of a Modernists like Le Corbusier or Kahn and their shills, we realize that there has to be more to this then the madness of crowds. We have mentioned institutions like Gropius' Bauhaus in past posts, but there is more to it than this as well.

Look at Le Corbusier's convent; the ugly post industrial footprint, the disconnect from the figures to the left, and the violation of what was a scenic landscape. The anti-human violence of this structure becomes much more explicable when we realize that Modernism was an overt globalist tool to undermine regional and cultural individuality. The UNESCO puff piece on "The Architectural Work of Le Corbusier, an Outstanding Contribution to the Modern Movement" makes it very clear that "these masterpieces of creative genius also attest to the internationalization of architectural practice across the planet."

Some quotes on the "merits". The text is remarkable for repeating the same empty statements without elaboration or defense. The only "value" seems to be the destruction of regional expression with abstract, meaningless,obscenities.

Of course, the "fundamental issues" are largely creeping globalist assault on human individuality, and UNESCO corruption is up to the usual standards of the UN. The destruction of human character and individuality is just business as usual.

Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, Wallace Harrison, and others, United Nations Secretariat Building, 1947-1952, New York

Note the design team.

So Le Corbusier cites masterpieces of ancient architecture as a justification for the destruction of all the organic offshoots and variations of these ancestors. A parallel should be coming into focus between this, and the various other "blank slate" thought crimes Modern utopianism. Marxists, Modernists, Futurists, Postmodernists, etc. all begin with the destruction of the past. Read the UNESCO screed and ask how this is fundamentally different from a New Soviet Man or forcing artificial, superficial, monocultural "diversity" onto unwilling communities?

Whether Le Corbusier was a willing tool or a useful idiot is less significant that fact that he is intellectually incoherent and a historical imbecile in a crowd of sycophants.The entire basis of his "plastic architecture" is objectively, incontrovertibly, factually dead wrong. There is no historical evidence, written or material, that even hints that the ancient Egyptians had a concept equivalent to the Modernist notion of "pure" forms. Their temples were purpose driven, meaning they were keyed to the religious and rhetorical expectations of visitors, and shaped according to cultural preferences rather than hallucinated whispers from the stones. A huge temple like the complex at Luxor grew over centuries, but the basic idea was the same as a Gothic cathedral: to create an awe inspiring visual experience that gives the impression of entering sacred space. It's the forms performing this function that are culturally specific.

Temple of Horus at Edfu, 237-57 BC, Edfu, Egypt; Model of the Horus temple of Edfu; Kestner Museum, Hannover, photo by Einsamer Schütze

Temple of Horus at Edfu, 237-57 BC, Edfu, Egypt; Model of the Horus temple of Edfu; Kestner Museum, Hannover, photo by Einsamer Schütze

The ancient Egyptians were polytheists (they worshipped multiple gods) and believed that with certain rituals, the spirit of a deity could be persuaded to enter a holy image called a cult statue. While there, it was especially receptive to prayers and offerings. Cult statues were extremely sacred, having actually housed a divine essence, and temples were conceived as a venue for this coming together of heaven and earth. This temple is new by Egyptian standards, but follows the centuries-old plan faithfully and is well preserved.

As the model shows, the temple was a sequential path from the outside world to the inner sanctuary, where the cult statue was housed. Notice the abundance of decoration.

In practical terms, the temple creates a progressive detachment from the world and provides an appropriately grand house for a god. But the appearance is an expression of a culturally-specific aesthetic, or visual language.

As the model shows, the temple was a sequential path from the outside world to the inner sanctuary, where the cult statue was housed. Notice the abundance of decoration.

In practical terms, the temple creates a progressive detachment from the world and provides an appropriately grand house for a god. But the appearance is an expression of a culturally-specific aesthetic, or visual language.

The ancient Buddhist stupa was also built to house sacred objects (relics of the Buddha), and to create an environment to help worshipers meditatively detach from the world. Functionally (spiritualized experience of a sacred item) and materially (stone post and lintel and rammed earth architecture) they are identical, but they look totally different.

The reason for this is what Modernist appeals to history invariably conceal: human meaning is a critical component to any healthy built environment. These monuments served completely different cultural and religious contexts, and while both valued simple masses, their chioces were driven by symbolic purposes, rather than sociopathy and animism. For ancient Buddhists, the circle was the basic representation of the endless cycle nature of existence, as communicated by the iconography of the dharmic wheel. Praying and meditating while processing around the stupa was thought to be conducive to the state of detachment central to Buddhist theology. The Egyptians used massive post and lintel stonework to overwhelm and impress with the magnificence of the deity. It is still imposing today, so it must have stunned people unaccustomed to such imposing structures.

But assessing historical accuracy gets even worse for Modernists. The “primal” forms of Egyptian temples were lavishly decorated with paintings, sculptures, and inscriptions that communicated very specific messages.

Computer reconstruction of the Luxor Temple. By analyzing pigment traces on the sand-scoured stone, modern researchers can accurately recreate ancient color schemes.

Reconstruction of the Great Hypostyle Hall, Karnak, circa 1290-1224 BC

Form and decoration are equally important to the mystical ambiance of the hypostyle hall, as are the expectations of the visitor, who must understand the meaning of the symbols and the experience that they convey. Organically evolved architecture is based on identities, and requires cultural awareness to feel its resonances. This is likely why globalists hate it so much.

It gets worse still. Even the structural elements also took on functionally unnecessary decoration. Note how the columns are divided into shaft and sculpted capital. The Egyptian column design was inspired by plant forms, the papyrus being the most recognizable. It is often assumed that the idea for this came from the use of wooden posts, but whatever the inspiration, it does not serve a practical purpose.

Karl Richard Lepsius, Egyptian capitals from the temple at Philae, from an expedition from 1842-1845 up the Nile into what now southern Sudan.

This drawing by a nineteenth-century archaeologist shows both the variety of plant-inspired designs, and the range of colors that could be used on them. Both the sculpted shape and painted design are completely arbitrary cultural preferences.

The entrance to an Egyptian temple was marked by a large structure called a pylon, which always had the same basic shape for reasons not determined by the materials. The nature of stone block construction imposes limits on the design, but the specific shape is an arbitrary symbolic choice that provided a billboard for more painting and sculpture.

Here is the ceremonial approach to the Temple of Amun at Luxor leading to the pylon entrance. The obelisk and row of sphinxes tie the temple to the surrounding landscape for rhetorical effect. A closer look shows some of the sculpture still exists.

The bottom image is the pylon from the temple at Edfu that we looked at earlier. It is in better shape, being almost 1000 years newer, but the consistent shape and use of decoration remains. Continual use within a national culture is how architectural forms and symbols become meaningful.

It is impossible to separate “essential” form from ornament in an Egyptian temple, because some of the structural elements either also have a decorative function or are designed specifically to support decoration. There is a reason why Modernists fixated on a notion of architectural history that looked more like a blurry photo of a ruin than any real approach to building. Le Corbusier likened massive ancient ruins to the hulking forms of grain elevators and industrial buildings as “proof” of the elemental connection between the venerable origins of architecture and the efficacy-driven designs of a modern industrial economy. Were he honest about what these buildings actually looked like, his entire dishonest claim of primacy vanishes in a puff of brimstone. Architecture has been used to communicate, control, and beautify since humanity first figured out how build a wall.

Iconography and style emerge organically from the interaction of cultural attitudes and available materials. They become meaningful associatively, through repetition and familiarity, sometimes outliving the culture that created them. Consider the afterlife of the pyramid as a funerary signifier.

Nubian Pyramids, begun circa 300 BC, Meroë, Sudan

Pyramid of Cestius, circa 18-12 BC, Rome

Both the Nubian and Roman people built pyramid tombs later in antiquity that were directly influenced by their contact with pharonic Egypt. Both were pitched at a steeper angle, but preserved the basic shape. The Nubian pyramids, which have been partially restored, are also interesting for their adoption of the pylon, on a much smaller scale, as a tomb entrance. When symbolic forms cross cultures, they are often used in new or unorthodox ways, since their deeper cultural resonances are lost.

The symbol survived into the modern age.

Canova, Tomb of Duchess Maria Christina of Saxony-Teschen, 1798-1805, Augustinian Church, Vienna

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Rapa Pyramid, completed 1811, Rapa, Poland

Richard E. Schmidt, Schoenhofen Mausoleum, 1893, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago

Sahlberg Mausoleum, 1902, Santa Barbara Cemetery, Santa Barbara, CA

Nick Cage’s Pyramid Tomb, 2010, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans

The Sahlberg Mausoleum is more conventional in its proportions, as is actor Nick Cage's revival of the motif for his New Orleans tomb.

In Postmodern hands, this sort of historical reference was cut off from its organically developed meaning and transformed into an empty spectacle. Remember, Postmodern architecture historicizes, in that it challenges Modernist dogma with arbitrary historical quotations divorced from their actual meaning or usage. At this point it is worthwhile to recall Benjamin (there are few times that this phrase will be heard around Band HQ) and his notion of history as a mass of disconnected allegories or ruins. Modernists like Le Corbusier need a ruined past to pretend their fetish for lumps and polyhedra have some sort of primal resonance. Postmodernists see the past as visual "discourse", a pile of aesthetic or conceptual ruins, without meaning beyond being vaguely historical, to be used according to the architect's imagination. Preferably in ways that are "daring", "bold", "dangerous", and/or "provacative", but not always.

Veldon Simpson, Luxor Hotel, 1992-93, Las Vegas

To look at the Luxor is to remember that Postmodern architectural theory was born in Vegas. It is a kitschy, superficial version of "splendor" that is more reminiscent of Stargate than pharonic Egypt. There is something spectacular about the sheer garishness, but it is pure postmodern "spectacle" or "simulacrum" than anything meaningful.

I. M. Pei, Louvre Pyramid, completed, 1989, Paris

Then there is Postmodernism as a globalist weapon. This alien, impersonal form invades one of the great historical centers of the Western tradition - the Louvre was the seat of the French Monarchy before becoming the world's preeminent art museum - while crowds of contemporary culture victims seal clap at the "cool".

Pei was a Harvard trained International School Modernist before mutating into a bit of a Postmodernist. The pyramid has a Modern appreciation for abstract geometric purity and a Postmodern allusion to history. The violation of the aesthetic integrity of the palace makes it a forerunner of Deconstructivism.

What does it say about the health of the "arts community" when a man who was not of the West, and who's education in the West consisted of the anti-Western propaganda of Modernism, is hired to deface one of the most significant collective architectural achievements in history? This is the globalist vision preached by UNESCO and other mouthpieces for the cabal.

Jack Kirby, cover for Fantastic Four vol. 1, 84, March, 1969, Marvel Comics

The photo of Pei tellingly uses a composition traditionally associated with looming menace.

John Byrne, cover for Fantastic Four, vol. 1, 247, Oct., 1982

This cover makes the looming Modernist threat more explicit.

It is possible to speak of ancient architectural “theory” but it is different from the way the term is used today. There was obviously a technical expertise needed for cutting and fitting stones, and there are aesthetic and functional consistencies (the decorated pylon at the entrance, the sequence of impressive spaces) that indicate a systematic approach to design. Because we have a solid understanding of Egyptian religious practices and social structures, we can connect buildings with the specific beliefs and ideologies that they were built to express. But this is based on an inductive process of building an interpretation out of the historical record rather than actual Egyptian texts on design.

Consistent columns in the Courtyard of Amenhotep III at Luxor.

There is some systematization in their designs - all the columns in a given area will be the same, but there is considerable variety between sites, or between different types of column at the same site. It is accurate to say that they had a systematic approach to building, but not a strictly theoretical one.

The Dawn of Theory: The Greeks:

This changes with the Greeks, who applied the same systematic thinking to building that they did to so many other fields. Ancient Greek culture is unique in the antique world for having appeared in what historically looks like an act of self-creation after the violent destruction of the earlier Mycenaean Greek civilization during the Bronze Age collapse. Historians have referred to the roughly three centuries after the destruction of Mycenae as the Greek Dark Ages, since there are no significant textual records and scant material evidence of civilization on the Greek peninsula. Then, suddenly, the poetry of Homer appears in an entirely new language, with the power and artistry that still ranks it among the greatest artistic achievements ever. During those dark centuries, the Greeks had devised a flexible new language based on the Phoenician alphabet that let them build an unprecedented intellectual culture predicated on finding order in a world of chaos. This reached an apotheosis in the philosophical schools of late classical Athens, where Aristotle theorized a cosmic order based on logical classification and causality, while the Neoplatonists conceptualized order on this world as a material expression of an ultimate metaphysical unity.

Rembrandt, Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer, 1653, oil on canvas, 143.5 x 136.5 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Greek culture was an act of willing order from the real chaos of the Bronze Age collapse. Here, Rembrandt captures the bond between the founder of this culture and its greatest mind, a bond that can only exist through bonds of nation or family.

This combination of logical empiricism and a desire to harmonize with higher principles is apparent in the evolution of Classical Greek art. Just like they did with their alphabet, the newly forming Greek culture took inspiration for their sculpture from an older neighbor. Archaic Greek statues were inspired by Egyptian models, but in the Classical period, sculptors achieved balanced works that were both more realistic and idealistic than anything seen before. This was accomplished by establishing a theoretical basis for human proportions and demeanor.

Statue of Seti I, Dyn. 19, New Kingdom, Ramesside period

Marble statue of a kouros (youth), circa 590–580 BC, marble, 194.6 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The kouros was a standard form of Archaic Greek sculpture derived from ancient Egypt. Notice the similarities in the frontal posture with fists clenched and sense of forward movement. The kouros is nude, however, foreshadowing the Green interest in the human body.

Doryphoros, 1st century BC-1st century AD Roman marble copy of Greek bronze original by Polykleitos from circa 440 BC, marble, 200 cm, Naples National Archaeological Museum

Egyptian sculpture remained remarkably consistent overt almost three thousand years, while Greek sculpture develops into into the Classical mix of realism and idealism seen in the Canon of Polykleitos. The serene seriousness of the expression and flawless, ageless physique provide the ideal, while the anatomical understanding and easy relaxed posture seem real.

The pose is a Greek invention called contrapposto (it's pronounced like it looks in English), and brings opposites into balance within a single figure. One leg is straight and weight bearing, while the other is relaxed and possibly stepping. The movement carries through the entire figure, with the tilt of the hips and shoulders reflecting the footwork in an musculoskeletally correct way. This not only makes the figure more lifelike by providing a sense of incipient movement, it increases dramatic tension by creating opposition then bringing it into harmony. Note how one side is open and the other closed, yet the figure seems balanced.

There is a similar pattern of development in Greek architecture from Egyptian roots to a theoretical system that is both idealized and humanized.

Temple of Hera, circa 550 BC, Paestum

Paestum was a Greek colony in the south of Italy with some remarkably well-preserved temples. This Archaic Greek example is an early example, and is still somwhat transitional in form. We can see the structural similarity to the older colonnade from Luxor, with the same massive stone post and lintel system supported by carved columns topped with capitals.

Greek religion also followed the Egyptian model of polytheism and cult statues in temple sanctuaries, but they conceived them in a different way. Classical temples were accessible only to priests and were designed to appear as perfect objects from the outside. And perfection to the ancient Greeks meant harmony and order.

Order was provided, appropriately enough, by the Orders, a standardized system of architecture built from the Egyptian stone post and lintel system. Three orders developed over time - the Doric, the Ionic, and the Corinthian - each with their prescribed features and ideal proportions.

There is nothing functional about these specific classifications; they are purely systematized decoration. In this way they acknowledged the human need for visually engaging buildings while also imposing a higher theoretical structure. In other words, a balance of realism (the human need for engaging architecture) and idealism in design.

Temple of Concordia, circa 430 BC, Agrigento, Sicily

The standard Greek temple was rectangular, with a few circular plans appearing later, with an elevated colonnade surrounding a closed sanctuary and topped by a sculpted entablature and pedimented roof. The order determined the appearance of the capital, the decoration of the entablature, and the proportions of the column.

The Doric was the first of the three orders to appear and was used throughout the Classical period. It is recognizable by its plain, circular capitals, thick, heavy looking columns and a pattern of alternating triglyphs and metopes running around the entablature.

The Ionic appeared at the beginning of late antiquity and featured thinner columns with a distinctive voluted capital with egg and dart moulding and a continuous sculpted frieze on the entablature. The Corinthian emerged in the fourth century and further refined the Ionic with even slenderer proportions and an ornate capital with stylized acanthus leaves. This order was not that common in Ancient Greek architecture, but was beloved by the Romans and later classical revivalists.

Temple of Athena Nike, circa 420 BC, Athens

Temple of the Olympian Zeus, circa 520 BC - 132 AD, Olympia, Greece. Corinthian colonnade started 174 BC

The orders are a unique historical development, and their consistent application indicates a theoretical basis to Greek architecture of a sort not found elsewhere. It is funny when we think of the arrogance of Modernists (and Postmodernists) in the arts, to realize that they were unable to approach the balance between idealized form and appealing decoration that the Greeks solved over 2000 years earlier. But there was more to Greek theory than just the orders, as the Parthenon, the centerpiece of Classical Athens and perhaps the most influential building of all time, reveals.

Parthenon, 447-432 BC, Athens

This temple was dedicated to the goddess Athena, the patron and namesake of the city of Athens. Though badly damaged, the distinct capitals, triglyphs, metopes clearly indicate the Doric order.

The ancient Athenians went to great lengths to achieve ordered perfection in their principle temple. Greek temples were generally built to simple harmonious proportions, but this one is particularly refined. There are subtle corrections throughout that compensate for optical distortions in our perception, such as the illusion of a slight curve in long straight lines, that make the building seem impossibly geometrically perfect.

Optical Corrections in Architecture, Parthenon, from Sir Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture, 20th ed. Architectural Press, 1996, p. 95.

This old diagram shows the adjustments to the Parthenon in an exaggerated way, to make them noticeable. In real life, they are too subtle to detect.

What is notable about these adjustments is that they distort the real geometric precision of the form to create an illusion of precision to our imperfect eyes. Even if we set aside the use of superficial decoration, the handling of form is enough to tell us that the Greeks took account of subjective experience in their most prestigious architecture and subordinated absolute theoretical purity to it. Intellectually, the Greeks were much more refined than the Modernists, and understood that “perfection” can only exist in this world in material representation, which makes it subject to the limitations and inclinations of human subjectivity. Modernists believe stones and I-beams talk.

Recreation of the color scheme of the Parthenon.

And there was abundant superficial ornament. Greek temples were painted and decorated with sculptures on the pediments, friezes, and elsewhere.

Top: reconstruction of the pediment sculpture depicting the contest between Athena and Posidon to be the patron of the city.

Bottom: detail of remaining carvings on the Parthenon frieze; original metopes in the British Museum. These reflect themes of the struggle between chaos and order at the heart of the Classical Greek world view.

Coloured detail of painted Ionic, from Kunsthistorische Bilderbogen, Verlag E. A. Seemann, Leipzig, 1883.

The effect of the paint is very different from our perception of ancient ruins, or the historical fictions of Modernist liars like Le Corbuiser.

What we see in Greek architecture is the same coming together of human experience and ideal order that we saw in sculpture. Of course, we are looking back at an alien culture over a vast gulf of time, which makes it hard to assess how common this theoretical attitude was historically, especially since we are largely dependent on Roman sources for our knowledge of this material. The Romans enthusiastically embraced Greek culture, but the later Hellenistic version rather than the Classical era. How theoretically determined was Greek architecture?

Napoleon Vier, types of Greek temple plans.

Despite the consistencies in overall form and use of the orders, there is considerable variation in the size and layout of these buildings. The classical system of architecture is scaleable because it is based on proportional relations. One can add colonnade length by adding width in the appropriate measure without theoretical limit.

Overall, then, we have a theoretical system based on harmonious proportions and the application of the orders that was flexible enough to operate on different scales and contained room for decorative elements specific to the building. It combined structural and ornamental components to accommodate the underlying principle of metaphysical unity in human terms. The historical record shows us that the rigidity of classical architecture is a later invention, and that the reality was more varied.

Cycling back to the Colosseum, we see evidence of both the Roman love and transformation of the Greek system.

Now we can identify the orders applied to the three stories of the arcade: the Tuscan (a simplified Roman version of the Doric) at the bottom, the Ionic in the middle, and the Corinthian at the top. But the orders developed as a structural part of a post and lintel system, while the Colosseum is a vaulted concrete building, meaning that their purpose here is purely ornamental application. This is apparent in how they are used, rising according to their relative elegance in a pattern intended to create visual interest. Yet it is a violation of Classical Greek principles to mix the orders capriciously in this way.

Temple of Bel, Palmyra,, founded 32 AD, Syria

In late antiquity, Classical architecture becomes a traditional aesthetic mode that gains weight from its historical connotations but loses its theoretical rigor and blends with other national styles. In this way, the architecture of late antiquity resembles the Beaux-Arts and Postmodern eras in the free use of motifs from the past.

Form and Function in the Middle Ages

The architecture that develops in Europe during the middle ages has important connections to late antiquity, but is transformed by broad historical factors into something completely different.

Reconstruction of longhouse Fyrkat, Himmerland, Denmark

Recreation of a Viking Longhouse

The Germanic tribes that overran the Western Empire had been ethnically and culturally disconnected from the peoples of the ancient Mediterranean, and had no monumental architectural traditions of their own. “Barbarian” buildings were of wooden construction, with high-pitched thatched or shingled roofs and small windows to manage the harsh climate. The later architecture of the Vikings is close enough to this to highlight the differences from the Classical tradition.

The ancient world was fundamentally transformed by the ascension of tribal, monotheistic cultures from what had been the periphery. Christianized Gothic tribes settled Europe and Western Mediterranean, while in the East, beginning in the seventh century, Arab Muslims swept away the Persian and most of the Byzantine Empires before spreading across North Africa, through Spain and into France. Ultimately they were stopped and pushed back across the Pyrénées by Charles Martell and the Franks, a Germanic people that never moved south into the ancient Mediterranean world. With the Ostrogoths and Visigoths essentially eliminated through Byzantine and Muslim wars, the dominant power in Europe had the least familiarity with Greco-Roman culture. Further north, in England and Scandinavia, the settlers were even more detached. Therefore, when the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne made a conscious to create a worthy imperial architecture, he was inspired by the buildings of Rome and Constantinople, but filtered through an outsider’s perspective.

Gatehouse of Lorsch Abbey, circa 800, Lorsch, Germany

Not much survives of Carolingian architecture, but this monastery gatehouse captures the blend of Classical inspiration and Germanic style. The triple arched entrance and application of the Ionic and Corinthian orders on the facade indicates an attempt to build along Roman lines. But the proportions are off, which the designer was not formally trained in ancient architectural theory, and the rest of the building is Germanic. Note the peaked roof, small windows, and unclassical geometric and strapwork patterns.

The lower image nicely contrasts the Corinthian capital Roman arch with the Germanic patterned decoration.

Gatehouse of Lorsch Abbey, circa 800, Lorsch, Germany

Not much survives of Carolingian architecture, but this monastery gatehouse captures the blend of Classical inspiration and Germanic style. The triple arched entrance and application of the Ionic and Corinthian orders on the facade indicates an attempt to build along Roman lines. But the proportions are off, which the designer was not formally trained in ancient architectural theory, and the rest of the building is Germanic. Note the peaked roof, small windows, and unclassical geometric and strapwork patterns.

The lower image nicely contrasts the Corinthian capital Roman arch with the Germanic patterned decoration.

When generalizing historical developments over a long time frame, it is necessary to identity and isolate sequences of innovation, or historical narratives. This is an abstract discursive structure that gets between us and reality, but it is a necessary accommodation to the scope of the material. It isn’t meaningless, as an intellectually limited binary thinking Postmodernist might think, but it is a simplification.Carolingian architecture, with its loose attitude to classical forms represents a point of departure, while the “narrative” is how structural innovation drove architectural aesthetics further from antiquity over time. Medieval builders initially copied the basic Early Christian basilica in their church plans before developing a completely new system of stone vaulting.

S. Maria Maggiore, beg. 435, Rome

St. Michael's of Hildesheim, conscrated 1022, Hildesheim, Germany

Pisa Cathedral, 1063-1092

If we look at a proto-Romanesque church like St. Michael’s of Hildesheim, or an early Romanesque one like the Pisa Cathedral, we see the same rectangular spatial configuration with a flat timber roof and columned nave that we find in an early Christian basilica like S. Maria Maggiore.

Basilica of Saint-Sernin, circa 1080-1120, Toulouse, France

The mature Romanesque introduced stone barrel vaulting, then groin vaulting to naves, resulting in fire resistant buildings that were more unified aesthetically by vertical elements that rise up the nave walls then carry into the roof vaults.

Cathedral Of Our Lady of Amiens, 1220- circa 1270, Amiens, France

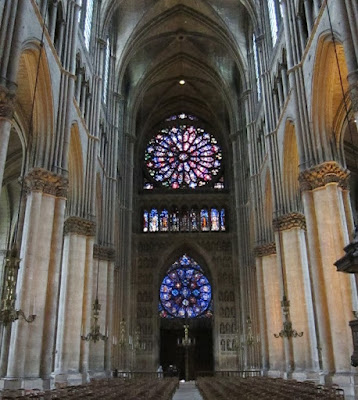

Gothic architecture was driven by efforts to maximize the amount of light coming into the interiors for practical and symbolic reasons. There are three technical innovations, all of which contributed to aesthetic developments as well. The use of rib vaults replaced the heavy Romanesque roofs with a much lighter structural web of load bearing arches, requiring less massive walls and buttressing to support. Replacing round Roman arches with pointed ones increased their strength, allowing a further reduction of mass. Finally, the invention of flying buttresses moved the supports fro the vaults away from the walls. This structural system is similar conceptually to the steel framing of a modern building, with the result that the walls between the supporting members are not load bearing and can be filled with glass.

The arched rib vaults can be seen here channeling the downward pressure of the roof onto the sturdy vertical supporting piers. Everything in between is free to for an opening or window. This was done entirely in masonry; the vaults were not reinforced with metal.

The flying buttress was the greatest innovation of the medieval mason and the key to the Gothic structural system. In channeling forces laterally as well as downward, vaults and arches face tremendous outward pressure, especially at the base. Flying buttresses surrounded the outside of these catherdrals and provide counter-pressure at the points where the vaults are pushing outward most strongly. This creates an equilibrium that balances the thrust of the roof and keeps the whole thing standing.

The old top photo shows them clearly, touching the exterior walls just below the roofline. The bottom is just a closer look in color.

The south transept of Amiens Cathedral shows how the Gothic vaulting system made the huge rose windows possible. Flying buttress push in, rib vaults push out, and the tension opens the entire wall up for a radiant vision.

With the Gothic there is an alignment of structure (buttressed pointed vaults), aesthetics (pointed stained glass windows and ribs), and function (a soaring evocation of the splendor of heaven). But it is still ornamental. In fact, the aesthetic appeal of the stained glass windows, and their ability to simulate the jeweled light of paradise, drove the development of the vaulting needed to make them possible.

Which brings us to one of the greatest rooms in the Western tradition, or anywhere else.

Pierre de Montreuil, Sainte-Chapelle, 1238-1248, Paris.

The Sainte-Chapelle was built by the French King Louis IX to house his collection of holy relics. On a sunny day, the experience is like being inside a gem, but less bright conditions also have their charm. Part of the appeal is the changing light.

The glass is everywhere. Look up!

The line from an early Christian basilica to a Gothic cathedral is a gradual process of organic, historical evolution into something completely different from its origins. There are principles in Gothic architecture; the vaulted structure, modular medieval building techniques, and theological implications of height and light were consistent across Europe, making it an international style. At the same time, it wasn’t theoretical in the sense that the same rule and proportions was ideally repeated for purely intellectualized reasons. Gothic cathedrals are all different, and are best thought of as individualized problem solving within a set of technical and stylistic parameters. There is no canonical model or models or critical authority to turn to for renewal. Rather it is an architecture that responded to the changing needs and desires of its community in a flexible and visually engaging system. Of course Le Corbusier found them unattractive for their lack of simple geometric form. Like a grain elevator. Or piece of broken column.

A Gothic cathedral was organic in another, more important sense, because it expressed the identity, unity, and faith of the community it supported. The appearance of the cathedrals reflected a growth in prosperity and urbanism in the later Middle Ages and the shift of scholarly and artistic leadership from the relatively isolated monasteries to the growing towns and cities. Local communities didn't just provide the labor force for their cathedrals, they supported them financially, and had their contributions memorialized for posterity.

St. Nicholas Window, circa 1210, Chartres Cathedral,

Chartres has the greatest collection of Medieval stained glass anywhere. Funds for windows were provided by local donors, who were represented in a panel. In the lower panel of the St. Nicolas Window, we see the merchants of dry goods, spices and medicinal drugs.

Bakers, farriers, and masons' guilds. Scenes like this are very valuable source of information on Medieval life for historians. The middle picture shows the use of a wooden frame when shoeing a horse.

The Gothic cathedral was a near-perfect synthesis of technique, aesthetics, and society in a package at once breathtaking and broadly accessible. The windows are visually spectacular, which makes them great for a blog post, but the interiors and exteriors were also covered in sculptures expressing everything from complicated typological relationships to humorous scenes of everyday life. It was this unity of culture and architecture that inspired the Romantics to medieval revivalism as a reaction to the early predations of Modernism.

Mike Campeau, Adobe recreation of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Cathedral Towering over a Town, circa 1830, destroyed, 1931

This is a fascinating project that used 162 Adobe Stock photos and over 180 hours of Photoshop to recreate a lost painting by an important German Neoclassicist turned Gothic Revivalist. What is important is how Schinkel captured the organic unity between the cathedral and its community.

Cola di Caprarola, Santa Maria della Consolazione, becun 1508, Todi, Italy