If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right.

The Band on Gab; The Band on Oneway

The last post set out to look at the English Enlightenment before getting sidetracked into the bizzarities of the Stuart Court. This was worthwhile because it began to clarify an alternative history that better reflects what appears to be reality. "Appears" isn't there to equivocate, but to acknowledge that we all look at the past through the darkling glass. Historical narratives are by nature just that - stories - that can only be as truthful as the available evidence. Authors write themselves, so any history is going to be bound up in the concerns of the present. All of this is fine. An empiricist recognizes that perfect understanding is impossible in this world, and tries to build as honest a position as possible while acknowledging their subjective limitations.

Norman Rockwell, Homecoming Marine, 1945, oil on canvas, Private collection

It is the Band's perspective, based on careful observation of recent events, that the fundamental crisis facing the West today can be framed as globalism vs. nationalism, or whether historical nations are free to live their cultures in their nations, or must succumb to the universal dictates of a central authority.

The ingredients of an organic culture - shared frames of reference, symbols, and traditions across generations - are present.

Given that anyone reading these posts knows secular transcendence literally impossible and a terrible idea, resistance to anonymous unaccountable global overseers is objectively a moral imperative.

Nationalism vs. globalism in meme form

What possible claim do malevolent liars and traitorous virtue-signalling idiots have on the rights of free people to associate freely? This isn't a rhetorical question: given the track record of "enlightened" human absolutisms, one has to have some combination of stupidity, arrogance, and outright evil to advocate such an existential horror. The Band generally dislikes labels, but the relatively recent coinage "omni-nationalist" corresponds to the notion that peoples have the right to pursue their own destinies in their own nations. The alternatives are inevitably monstrous.

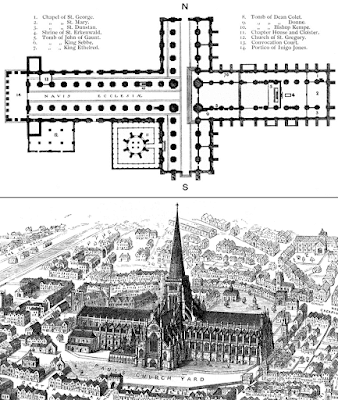

Inigo Jones, The most notable antiquity of Great Britain, vulgarly called Stone-Heng on Salisbury plain London, 1655

In this posthumous publication, Jones constructed a false history of Stonehenge as an ancient Roman temple to the sky god Coelus. The actual facts were replaced with a a fiction that conveniently supported Jones' imposition of Palladian architecture on England.

The point is not to single out Jones, but to illustrate how serving an absolutist ideal subordinates the empirical search for truth to self-serving fantasy. Anyone following "climate science" or the reproducibility crisis is well aware that the pressure to serve the ideological master is alive and well today.

The last post presented history as the subjective representation of a real past, making it a mediator between our limited perspectives and something that happened, but can't be known it itself. We experience of time as a linear movement of sequential events linked by causal relationships, which makes narrative an obvious medium for recounting history. But writing historical narratives is distorting, and lends itself to imaging directions or purposes in history that are not actually present. Let's look more closely.

The poor child just had to wait for Modernism...

Excerpt from Finnigans Wake by Modern genius James Joyce.

Narratives are human creations that are structured around a unified plot. There are Modern exceptions to this, but no one reads them, so we are safe to use this as a working definition.

The presence of a plot imposes a dramatic unity on the narrated events that gives them a significance within the story that they would not necessarily have as part of the background noise of everyday life.

The plot, or thesis, for a historian involves selecting and bracketing historical details to demonstrate a particular causal sequence.

The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand triggering World War I is an example of this. The problem isn't that it is inherently wrong, but incomplete. For every chain of events that is selected, a virtually infinite number is not - in this case, all the factors leading up the the onset of the war. Even the most accurate account is only one small piece of a much larger, interacting multi-dimensional puzzle. But the act of curating the information and writing the historical plot gives the particular narrative a weight that it doesn't really have.

"Das Stufenalter der Frau", Chromolithographie, circa 1900, Germanisches Natoinalmuseum HB19534, Nuremberg

This is made worse by the fact that the structure of our own lives inclines us to see history as moving along a fixed track. Humans, like all organisms, are teleological, in that our lifecycles are genetically predetermined, at least in the broad outlines. We are born, grow old, and die in predictable ways.

Our subjective frames of reference mean that we relate to things in terms of our own lifecycle, since it is human nature to contextualize events by their impacts on us. Our personal histories provide a natural narrative sequence as well. We tend to interpret our experiences by their impact on our growth and development, which gives them a unified narrative dimension that they don't actually have. Where history writing went wrong was in transferring the idea of teleologies and causal chains to the the movement of time that history represents. There is nothing wrong epistemologically with accepting metaphysical forces on faith, because this is where such knowledge belongs. The falsehood is in claiming that they are knowable through human reason alone. Like many globalist lies, this one vaporizes with a moment's thought

Earlier posts have looked at the ontological incoherence of presuming a guiding force above the natural - literally the supernatural - from an atheistic or materialistic perspective. We looked at Hegel's spirit of history and Marx' idiocy in particular, but these are merely cases of the myth of Progress that attained metaphysical status during the Enlightenment. But the unfortunate reality is that progress is relational, not an ideal value; it needs a frame of reference. One cannot "progress" without progressing towards something; otherwise it is simply random movement.

We know from personal experience that things progress - technology, individuals, cultures, etc. can all be assess in terms of movement towards a goal or goals. But how do we measure this for something as fragmented and all-encompassing as the passage of time?

Hence the need for teleology. In the premodern West, this was provided by Christian historiography that mapped a universal history from Genesis to Revelation, while providing a framework for the progress of the individual in the world.

See the Enlightenment problem?

History, like the human experience of time that it represents, is narrative by nature, which implies a guiding plot, or teleology. This worked fine from a Christian perspective, since history is divinely teleological, but the legacy of the Enlightenment was to reject the divine. But teleology is by definition above the natural - literally super-natural - and there is no logical or empirical proof for supernatural forces. That's WHY they're supernatural. So this leaves only the weight of the author's persona for authority, and while that is appealing on an ego level, it deprives their work of broader significance.

It is common for people to pluck quotes from famous thinkers and set them on evocative backgrounds, in the vain hope that profundity is transitive. Here are two such memes from the old Spirit of History himself. They both profess a universal sentiment, but contradict each other. Both can't be true. In fact, neither are. So why on earth is anyone flying these as the intellectual banner? Because a somber portrait is included?

The appeal of "rationalism" is the ultimate empowerment of the human, but its so-called champions literally idolize logical and empirical falsehoods in the name of "truth". This Orwellian ontology - "reason" means accepting objective lies as faith - is typical of authoritarian thought because it has no actual grounding in human nature, no empirical truth, to legitimate it. The key was to appeal to vanity. At the root, all the teleological spirits of history, the movements of the people, etc. are just phantasms to make self-interested and ignorant historians' stories real.

|

| Josephine Wall, The Storyteller, 1993, acrylic on Masonite, 20×20 |

Broad histories are made up of chronologically arranged periods that have to be general to accommodate wide spans of time. It would be ridiculous to expect someone writing a history of the West, for example, to be comprehensive.

Thomas Moran, Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower Came, 1859

How do you look back over the endless landscape of the past and pick a destination, let alone decide what details are important? Easy...

You write a story.

There is a basic outline, or plot, that Modern histories almost always follow. The period divisions will differ in number and name, but their arrangement always tells the same story. This graphic takes five large areas that are always present in some form or another and puts them in sequence to clarify this narrative structure.

Stained glass window in Prague Cathedral.

Leonardo, Vitruvian Man detail, circa 1490

John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence, 1817-19, oil on canvas, 3.7 × 5.5 m, U.S. Capitol, Washington, DC

Alexander Graham Bell at the opening of the long-distance line from New York to Chicago, 1892. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

1950's America, the peak of high trust prosperity.

If you've read many big area or world histories, you will have noticed that the specific periods and their ranges can differ, the general pattern is the same.

It is true that general histories have to be oversimplified, but simplicity reveals general structure. If we look at our graphic as a story board and the periods as main plot points, we have the basic narrative outline behind ANY historical account that accepts this period sequence. And what we see is the move from a unified world view, to fragmented competing human authorities, to the establishment of reason, to the material fruits of a rationalistic society.

The Durant's massive project is one of, if not the most extensive summaries of Western history. Unfinished at the time of the authors' deaths, it plotted the familiar progressive journey from religious credulity to Enlightened knowledge.

The opening to Chapter 18 of volume 8 is reproduced and linked here. The pernicious myth that the Enlightenment transformed humanity from Voodoo priests into dispassionate, analytic truth-speakers has to come to an end. Think of the "knowledge" that Enlightenment "reason" has unleashed. The authoritarian falsehoods imposed like a boot on captive peoples. The erasure of cultures and a raging, solipsistic materialism that threatens to consume the world.

Notice how the focus of the values changes, from the divine (Age of Faith), to the intellectual (Age of Reason), to the consumptive, or purely emotional (The Age of Stuff?). This actually inverts the traditional metaphysical hierarchy of value, both Classical and Christian, where the move from body (animal) to mind (rational) and soul (spiritual) represented increasing nobility and refinement. It is literally a transition from the highest principles to the most basic appetites, but the veneer of "progress" makes this seem purely positive. In other words, historians pull the old philosophical bait and switch and combine completely different things into the same category. What begins as a cultural/ philosophical development is somehow reduced to mapping technological development.

The test of any heuristic is whether or not it is predictive.

The Jetsons, a cartoon by Hanna-Barbera that aired from 1962-62.

Stat Trek was produced from 1966-69 by Norway Productions, Desilu Productions, and Paramount Television

According to the modern model of historical progress, life should be becoming increasingly Utopian as the replacement of the divine with techno-centric solipsism bears fruit. The popular mid-twentieth-century image of the future made it seem that way anyhow.

That's "Progress". Let's check reality/

Wait. This doesn't look like progress.

Declining social trust and intelligence, while income disparity widens? Mass immigration of radically incompatible populations. Hollowing out of institutions. The construction of a massive surveillance state. The invention of countless thought crimes in the name of the wildly misnamed "social justice".

Look at the bottom graph. See the 50's? This is where the switch in the nature of progress noted above - from epistemological to purely technological change - comes home to roost. Believing their improving standard of living signified improvements in human nature, they had no idea where their cohesion and social values came from. How could they? They were deceived by their most trusted institutions.

Today "progressives" have redefined progress as the destruction of the Western values that made their coddled lives possible. Their success is visible, appropriately enough, to the left. In reality, they are simply liars, because the empirical facts are starkly clear:

Progress is self-evidently not the driving theme of history

It would be easier to consider history as a set of progressions and regressions, with no material forces other than circumstances determining the outcomes. The technological advances since the Industrial Revolution are remarkable, and we live with more material comfort that most have throughout human history. But it is clear we are devolving in intellectual, social, and spiritual terms. Here's a different sort of progress:

Chauvet Cave painting, circa 35,000 BC, near Vallon-Pont-d'Arc, France

Nannar, (Sumerian), 2nd millennium BC, bronze, 12 cm, Private collection; Hathor (Egyptian), 1549/50-1292 BC, Luxor Museum, Egypt; Zeus (Greek), 1st century AD, marble, Getty Villa, Malibu

Consider the developmental stages of abstract reasoning. The first step beyond pure environmental reaction is to

assign supernatural causes to events. More sophisticated is the ability to conceptualize a fixed pantheon in a unified mythology.

Raphael, The School of Athens (detail), 1509-11, fresco, Vatican Museum

Gustave Doré, The Triumph Of Christianity Over Paganism, 1868, oil on canvas, 299.7 x 200. 6 cm, Private collection

Greek philosophers make the next jump in abstract thinking, conceptualizing reality as a totality beyond the whims of individual deities, and determining what lies within human knowledge. Christian theology advances metaphysics by addressing eschatological questions and solving the problem of beginnings.

From this perspective, our contemporary materialism seems animalistic, while our "higher-order" thought - the nonsensical secular transcendences, fictions about human nature, even absurd designations like "hate" speech - fail to rise above a shamanistic desire to speak raw desire into reality. And modern "spirituality"? The gamut of post-New Age fabulists can't muster a coherent metaphysics and remain stuck between animism (various disjointed occultisms) and polytheism.

Photo from Lauren Greenfield's 'Generation Wealth', chronicling "unprecedented global obsession with wealth and materialism".

Pieter Boel, Large Vanitas, 1663, oil on canvas, 207 x 260 cm, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille

Vanitas paintings warn against becoming attached to worldly status or possessions. They consist of symbols of wealth, power, and/or knowledge in decay or disarray, with symbols of death and the passing of time.

"What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun? One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever" Ecclesiastes 3-4 (KJV).

This type of theme is a momento mori, or a reminder of death.

Stephanie Pui-Mun Law, image from The Art of Shadowscapes Tarot

Josephine Wall, Earth Angel

Wiccans commune with their earth deity

Venus of Willendorf, circa 30,000 BCE, limestone, 11.1 cm, Natural History Museum, Vienna

The various forms of New Age "spirituality" that doesn't cross over into actual occultism suffer from an insurmountable self-perception gap. The inspirational art can be quite lovely. The reality less so.

All joking aside, these alternative spiritualities lack even an internally coherent metaphysics and are best thought of as the cry for help of a people severed from real fulfillment by modernity. In some ways they could be pitied, were their slack narcissism, the need for easy self-affirming answers, not so culturally toxic.

Materialism, tribalism, and self-centeredness don't sound like progress. Where do we find a historical teleology in any of this?

It is obvious that our self-serving narrative of progress, where we currently occupy the endpoint, is untrue, and to continue to pretend otherwise is like proceeding with a math problem when one step is wrong. History is random. Even the most hardcore believer in biological determinism has to admit that the sheer number of human interactions is far too complex a web to possibly predict. In this context, any teleology is by definition SUPERnatural, or literally above nature. To be coherent, or even logically possible, a rationalist has one of three options: offer a logical proof, admit that they are acting on faith, or keep lying.

John Tenniel, An Allegory of the Great Industrial Meeting of all Nations, 1851, oil on canvas, 57 x 107 cm, Private collection.

The 1851 World's Exposition, the first World's Fair, was to be a showcase for British technological achievement. It celebrated progress in science and industry, which can be observed objectively. But in transforming what was essentially a tech boom into the allegorical language of academic fine art, pictures like this give the impression that the progress is a deeper thing, implicit in the people themselves. This message is nationalist, since Britain is central, but the notion that progress in an area is somehow the same as human progress as a species towards some shadowy teleology can be misapplied in any context.

Real Progress

At the same time, it is clear that technology, and collective standards of living increased radically after the Renaissance. Claiming progress in history may be a fallacy, but there are progresses that, if large enough, create the illusion of historical movement. Since rational progress is a historical myth, and Enlightenment rationalism came after systematic empirical thought had become established as the scientific method, it is possible to see how an alternative historical narrative would reframe the notion of progress.

Alexander Leydenfrost, Science on the March, for Popular Mechanics 50, January, 1952

There are progresses that, if large enough, create the illusion of historical movement. Centuries before the Enlightenment, the burst of empirical knowledge known as the Scientific Revolution triggered the continual growth in material wealth that accelerated during the Industrial Revolution and into the Modern era.

By now it should be clear that rationalism and empiricism are epistemological opposites. The problem is that their semantics make them confusing. How many of you wouldn’t have been surprised, at some point in your lives, to find out that Enlightenment rationalism consists of dogmatic adherence to empirical falsehood? The difference between reasoning, or the process of figuring something out logically and Reason as an absolute standard of truth. What exactly is this “reason”? We know it isn’t based on objective facts, and that any form of inherited wisdom went out the window. It fits the profile of an article of faith, but the legitimate place for that sort of knowledge is in domains that are not empirically verifiable. The one thing it does have is the tried and true appeal to vanity, which can motivate humans to profess almost anything.

Carstian Luyckx, Allegory of Charles I of England and Henrietta of France in a Vanitas Still Life, 1670s, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museum of Art

Another vanitas. Here, the cultural aspirations of the Stuart king and queen are joined by a skull, a recently extinguished candle, and soap bubbles, which symbolized the fleeting fragility of beauty. Vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

Let's consider the Scientific Revolution in broad terms, since it is the name historians give the events leading to the Modern faith in human "reason". Since there is way more here than can be summarized in a post, we will just focus on how rationalism somehow hijacked the epistemological validity of empiricism in the name of "science". What we will see is the familiar bait and switch, as the systematic testing of hypotheses magically becomes an authoritarian belief system based on an objectively false ideology.

Scenographia systematis Copernicani, in Andreas Cellarius' Harmonia macrocosmica seu atlas universalis et novus, totius universi creati cosmographiam generalem, et novam exhibens, Amsterdam: G. Valk und P. Schenk, 1708.

The publication of Copernicus' heliocentric model of the cosmos (the sun in the center, rather than the earth) in 1543 is seen as a groundbreaking transformation in thought.

Symbolically, moving humanity from the focal point of the cosmos broke the comforting metaphysical unity of Neoplatonists and Scholastics alike. The entirety of the microcosm/macrocosm theories of Virtuvian harmonies was based on man being the measure, or humanity at the center. In theory, this clears the way for empirical science by clearing away inherited myths and starting the process of building knowledge through observation and logic.

Historian Thomas Kuhn has referred to Copernicus' impact as a revolution in its own right, since it triggered a widespread change in epistemology. This is consistent with Kuhn's more famous work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, where he constructs a large historiographic framework around epistemological paradigm shifts. It is limited in detail, as all broad histories of this nature are, but his model is very intelligent and well worth your time if this sort of thing interests you. The problem is that the empirical approach embodied by Copernicus is not what science became, and thinking of Copernicus as the revolutionary who changed everything obscures the continuing transformations and corruptions of science that were unfolding within this new paradigm.

The burst of empirical discoveries in the seventeenth century certainly deserves the title of revolution. In field after field, methodical observation led to new verifiable knowledge that could be build on by followers.

Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel: Johannes Oporinus, 1543; 'Studio of Titian', title page and drawings to hand-colored dedication copy presented by Vesalius to Emperor Charles V

Andrea Vesalius' Fabrica came out in the same year as Copernicus' work and had a comparable impact on the understanding of anatomy. By performing disections and carefully recording his results, Vesalius provided a more accurate account of the human body, including the identification of the heart as the source of blood circulation. His magnificent text was illustrated by the workshop of Titian, the dominant painter in Renaissance Venice and one of the most significant painters of all time. The pictures are a treasure in themselves, combining art and science in an original way.

The title page was black and white, but special copies, like this one for the emperor, could be colored. The Band chose this one because it is more legible for the reader. See how Vesalius depicts himself in the midst of a dissection. The skeleton pointing behind him provides the same moral as a vanitas image - momento mori, or remember death - but the authority for his information is based on empirical observation. The reality was that Vesalius held many erroneous presuppositions, but what is important is the principle that reliable knowledge can be obtained "scientifically".

William Harvey, De motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus, anatomica exercitatio, Frankfurt: Sumptibus Guilielmi Fitzeri, 1628

Because Vesalius based his work on observation, other could build on it. Harvey figured out the mechanism of blood circulation in this book. The one picture indicates his authority: an experiment he set up to prove his hypothesis.

The Scientific Revolution took place all over Europe, since it had its origins in the intellectual upheaval of the Renaissance. This may sound odd, given the emphasis on ancient authority in humanist thought, but it makes more sense when we think of it as a progression.

A. Hirschvogel, Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim [Paracelsus], 1538, etching, reproduction, 1927, Wellcome Collection, London

Steven van Calcar, Portrait of Andreas Vesalius, circa. 1535-45, Hermitage, St. Petersburg

Attributed to Daniël Mijtens, Portrait of William Harvey, circa 1627, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery

This is progress - steadily increasing knowledge through observation, reason, and logic. The endpoint can not only be reached, it can be verified when it is. The inherited belief about circulation was gradually broken down and replaced with an empirical model that objectively accounts for the movement of the blood in the body. Obviously medical knowledge continues to grow, but if it is sound, it is based on the same messy process of empirical progress.

Empirical Architecture?

The empirical bent of the English can be seen in the architecture of Christopher Wren. In fact, thinking about him through this frame of empiricism vs. rationalism that we are trying fleshes out the standard account of his style. Wren was a mathematician and astronomer before taking up architecture during his evolution into something of a polymath, and taught himself architecture by examining what was going on in the recognized cultural centers of Europe. Designing a grand cathedral for a newly restored king, this meant Paris and Rome, or Michelangelo via Louis' French Baroque.

John Closterman, Portrait of Christopher Wren, circa 1690, oil on canvas, 143.3 x 121.4 cm, Royal Society, London

A brilliant thinker, Wren epitomized the scientific culture of late seventeenth-century England. His academic appointment was as an astronomer, but he made contributions in mathematics, optics, mechanics, microscopy, surveying, and meteorology, among other areas.

A founding member of the Royal Society, Wren gave the lecture at its first meeting in 1660, and serving as its president from 1680–82. Architecture was merely an extension of his interest in math, physics, and engineering.

Christopher Wren, St. Paul's Cathedral, 1669-75, London

Wren's masterpiece fits generally with the style of the Baroque, but it doesn't have any one particular model. Not having apprenticed as a builder or architect, he combined and improved on different influences to create something traditionally meaningful but new.

The usual comparison is with Michelangelo's dome of St. Peter's. Both are massive ribbed domes ringed by columns. But the similarity is more general than specific. Wrens colonnade is a more strictly classical ring, while Michelangelo paired his columns and projected them at the entablature to create a more energetic effect.

Wren's dome is also taller in proportion...

This solved the problem of the visibility of the dome behind the facade. Michelangelo's dome was designed without plans for a long nave extending from the crossing, so when Maderno added one, it cut the sightline to the dome. Wren planned a long nave from the start and made the dome taller to compensate.

Wren stretched the dome without increasing the lateral thrust by designing two different domes - a round one to be seen from the inside, and a stronger conical one to raise the lantern the extra height. A lighter wooden frame to support the round outer roof.

Notice how the ring of windows open below the inner dome, while the conical vault carries the weight of the lantern directly to the walls of the drum.

Better vaulting meant that the building needed much less massive walls to support the weight of the structure. Compare the plans of St. Peter's (above) and St. Paul's. Solid black areas represent walls and other masses; the dotted lines are vaults and openings. Notice how much less area is taken up by walls and supports on Wren's plan. Even his dome rests on relatively slender piers, and the domical vaults of the nave are also better at managing weight.

Old St Paul's Cathedral in London, W.H. Prior, Typographic Etching Co., Pub. c.1875)

The unusual layout of Wren's building, with the choir and nave nearly the same length, followed that of Old St. Paul's, which had burned in the Great Fire of 1666. This way all of the earlier holy ground was covered again by the new structure. Compare this to Michelangelo's rebuilding of St. Peter's, where his central plan did not encompass the original.

This points to the difference between theoretical approach to architecture and an empirical one. Michelangelo insisted on an abstract geometric ideal that was ill-suited to the actual project. Wren devised his solution by examining the initial conditions, then devising a a plan that best fit.

Palladio, Villa Cornaro, 1552, Piombino Dese, near Venice

The two-story portico on the facade was of Palladian origin, but was also popular in the French Baroque. Here we see Hardouin-Mansard's variation for the Church of the Invalides of roughly the same time as Wren's. The decision to pair the columns seems to be Wren's own.

The case of St. Paul's visualizes the difference between empirical and rationalistic approaches to architecture. Wren considers the project needs - a replacement cathedral under a Restoration monarch - then combines the appropriate symbolic and stylistic elements in a form that is meaningful and locally specific at once. He then uses his mathematical skills to improve on his predecessors, creating a building that celebrates English ingenuity as well. Technical progress with a clear aesthetic message. Michelangelo on the other hand insisted on the circle and square geometry that expressed humanistic ideals, but were poorly suited to client needs. The decision to add a nave wasn't just symbolic. Without one, where would the congregation sit?

Barma and Postnik Yakovlev, St. Basil's Cathedral, begun 1555, Moscow

A Postmodernist would "call into question" or "problematize" the notion of "progress," since these sad, vain creatures confuse the blatherings of their sad, vain predecessors with reality. Progress is relationally defined; there is no such thing and universal material progress to deconstruct. St. Paul's represents technical progress in making huge, masonry domed buildings lighter and airier. Others may define progress differently, which is why we have cultures.

Wren didn't need anyone to tell him that there was no ideal house of worship, no place where human theories of geometry can impel God's grace. If a church is "holy ground", it is sanctified by the accumulation of Christian faith that happens within its walls, not by the plans of a clever architect.

England was filled with churches in different shapes and sizes. There are similarities arising from local tastes and customs, but no external set of theoretical rules. This is architecture from the bottom up - "empirical" architecture, where cultural forms develop organically and express a message that is intimately bound up with its community. There is a freedom here from the vile peddlers of fake transcendence and their bare animus towards community and tradition.

Towers and Steeples built by Wren from Charles Knight, Old England: A Pictorial Museum, London: James Sangster and Co., 1845

Wren was tasked with designing fifty-one churches after the Fire of London, twenty-three of which remain. His steeples are where his creativity is most obvious - a series of unique, attractive and completely original monuments with classical and medieval elements. His goal was pleasing variety, not rule-based vanity.

So how is it that Wren and his creative Baroque was the toast of London around 1690, but just a few decades later, Palladian theory is becoming the law of the land?

Colen Campbell, Houghton Hall, 1722-35, Norfolk, England

Campbell was the first significant Palladian revivalist. The corner domes on this estate were added later - the original design was as simple and austere as anything designed by the Venetian master.

Architecture is the physical expression of a society. Not just the high-end architecture sponsored by big clients or found in history books, but the ways people organize their communities and living spaces. It's not completely random, since we inherit cultural forms and there is a momentum to crowds that drives trends. But it is not completely fixed either, or at least it shouldn't be in an healthy society. So when we see a fairly quick change from an open, experimental attitude to a strict, theory-bound Palladian classicism at the highest levels, it is an indication that something is happening in the larger society.

Newton is a sort of nexus for English empiricism and Enlightenment rationalism because his Principia accounted for the observable problems with earlier cosmological theories while seeming to rise to the level of absolute law. We remember that Newton himself was deeply religious, but his spiritual and scientific, for want of better terms, were kept separate. His reasoning appeared so sound and self-contained that atheists could hold it up as "proof" that the human mind can reach universal truth.

Jean-Leon Huens, Sir Isaac Newton, gouache on paper on board, 16.5 x 24.1 cm, Private

The irony is that Newton would have hated the idea of being turned into this sort of absolute authority. Despite the scope of his theorizing, he was rigorously experimental like Wren, Hooke, and his other Royal Society friends.

In the twentieth century, quantum theory would reveal the limits of Newtonian physics, causing self-important theorists to theorize self-importantly about loss of certainty in the (Post)Modern age. It was commonly assumed among many of the "science minded" Postmodernists that "relativity" meant everything was relative, and therefore reality was subjective. This isn't a joke.

Early in his career, Derrida drew a parallel between relativity and his own deconstructive philosophy. Note the signature move of turning simple statements into tortuous mazes of asides, ellipses, and digressions.

The hair as well.

Deconstruction sold itself as the end of the "Western metaphysical tradition" - the radical inversion of all master narratives and the very concept of truth, and the liberating end to the false certainties of the Enlightenment. They were actually right on one thing: There never was "certainty." It was all an illusion. The rationalist universe was just the projected wish fulfillment of vain little men. It's so-called deconstruction was just more of the same.

One of the pleasures of the Band is being able to move across periods and subjects, because sometimes new possibilities jump out. Let's indulge one of these, and see if it looks useful. The premise: early modern philosophy of the Enlightenment is an important forerunner to Postmodern theory because it establishes the fiction that there is a special discursive space where clever people ascertain transcendent truth. We will think very generally at this point.

Apparently it has become problematic that universities prefer hiring the intellectually rigorous philosophers. Gender may be involved. The graphic is from 2013, but it is doubtful that continental philosophy has become more plausible since.

Coëtivy Master (Henri de Vulcop?), Philosophy Presenting the Seven Liberal Arts to Boethius, circa 1460-70, Consolation of Philosophy, Ms. 42, leaf 2v, Getty

Philosophy, or the love of knowledge, presided over the Liberal Arts in the Middle Ages as the highest of human "sciences".

Coëtivy Master, (Henri de Vulcop?), Philosophy Instructing Boethius on the Role of God, 1460 - 1470, tempera on parchment, 7 × 17 cm, Consolation of Philosophy, Ms. 42, leaf 3, Getty

It was sometimes known as the "handmaiden of theology", and as the highest level of human understanding, aligned with God's creation.

Raphael, Plato and Aristotle, from The School of Athens, 1509-11, Vatican Museum

Notice the gestures of these two. Plato points upward and holds his Timaeus, a work that deals with metaphysical topics. Aristotle reaches outward and down, representing his mastery of earthly knowledge, and carries his Ethics. Premodern philosophy dealt with the entirety of human knowledge, not one small corner of the Arts Faculty building.

Giovanni di Paolo, The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise, 1445, tempera and gold on wood, 46.4 x 52.1 cm, Met

Christianity resolved metaphysical questions, but was complimented by philosophy. Here we see divine creation, the cosmology of the philosophers, and the Edenic roots of Christian ethics in one single picture.

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632, oil on canvas, 216.5 × 169.5 cm, Mauritshuis, The Hague

Jean Huber, Philosopher's dinner, 1772, Voltaire Foundation, Oxford University

Prior to the Scientific Revolution, what we would call "science" was a subset of philosophy called "natural philosophy". Once empirical science became the primary tool for gathering knowledge, philosophy developed into an isolated discourse endlessly masticating unverifiable thought experiments.

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Nicolaus Copernicus for monument in Warsaw, circa 1825, Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen

So to generalize - remember that we are painting in broad strokes - the Scientific Revolution splits inductive empirical (scientific) facts from rationalistic, theoretical (philosophical) principles. The division was never this sharp, but it should be clear that the experimentalists of the early Royal Society were completely different epistemologically than the Utopians of the Enlightenment.

The idea that academic Postmodernism was a consequence, rather than a failure, of philosophy is not one that the Band has worked through, and we will not make more of it right now. But we can see that it does apply specifically to the transformation of English Empiricism into something more in line with the fake transcendence of Enlightenment rationalism. More specifically, John Locke and the mystical transubstantiation of empiricism into... Empiricism.

Richard Westmacott, John Locke, circa 1808, marble, University College London

Adding an -ism turns empiricism from a method to an absolute principal on no empirical grounds whatsoever. Abandoning charity for the sake of brevity, Locke essentially declared that because we can figure things out, all thoughts must be entirely due to sensory inputs. He was arguing against the notion of innate, or a priori, ideas, but lacked the knowledge of genetics to properly frame the issue. The problem isn't that he championed sensory knowledge or was limited by his time, it's his absolutism. Because he was so influential, and his account oversimplified to the point of error, his intellectual failings have been tremendously destructive.

The refusal to admit innate impulses overvalued "education" and legitimated so much dehumanizing "socialization". Locke gets bonus points for the idea of the blank slate, the pernicious falsehood that has undermined the West with ideas like "melting pots" where aliens with IQs two standard deviations below the national average can be imagined into "citizens".

The intellectual vanity of the Enlightenment is evident in the decision to clothe the seventeenth-century Locke in Roman robes.

This is the key inflection point, where the empiricism of the Scientific Method is recast as another type of secular transcendence: human improvement through reason. It is the philosophical equivalent of John Tenniel's painting mentioned above, where industrial progress somehow becomes teleological. It is not a coincidence that Locke got a lot of uptake among French thinkers like Rousseau and Voltaire. And the timing was perfect; the Scientific Revolution uncorked almost two centuries of British wealth and power, which allowed the Enlightenment rationalists to claim credit.

Progress... it's fantastic, until it isn't.

Henry Hoare II, Stourhead House Gardens, 1741-80

No comments:

Post a Comment