If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and reflections on reality and knowledge have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check a couple times a day and it will be up there.This is the second part of the Gothic art wrap-up. These art posts have a way of sprawling, so we're going to take up from where the first part ended instead of spending time recapping. Here's the link to Part I for the backstory. It's still crazy long because of all the big pictures, but we got through it. The main subject of this part is the International Gothic, a refined style of art that spread across the noble courts of Europe. But not just the art characteristics - what the International Gothic movement can tell us about the formation of the arts - and by extension the culture - of the West. Art is a visual artifact of the historical past that addresses our relationship with larger realities. So let's see what it shows us.

The Master of Catherine of Cleves, Catherine of Cleves Praying to the Virgin and Child from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, The Netherlands, Utrecht, ca. 1440

Court style and luxury are hallmarks of the International Gothic. The prominent heraldry shows the importance of noble bloodlines. But there is also real tenderness in how Jesus reaches for his mother. And note how Catherine is kneeling in devotion. There is a strong link between the beauty we've been associating with courtly materialism and legitimate faith. That's why the late Middle Ages presents the newborn visual arts at a crossroads.

Part I drew some conclusions about art in general then identified common patterns in English and German Gothic. It capped a series of posts on Gothic art against a backdrop of evolving history with the idea that the art of the West was born at a crossroads. A bit overdramatic - the two paths we identified overlap a great deal. But art was a product of the forming international aristocratic elite class and defined by it's expression of Christian logos through skilled mastery.

Part II will look at two major late medieval tendencies as paths. There are a lot of big pictures here and we tried to find good quality ones. Part of understanding the International Gothic is being able to see core similarity behind difference. This is a valuable skill to practice, because being able to see general impressions connecting individual things is applicable everywhere. So look for what it is that ties these pictures together. Your perspicacity will be the big winner. The two paths -

Geertgen tot Sint Jans, Christ as the Man of Sorrows, around 1486, oil on panel, Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht

The first is is an intense form of religious art that tried to trigger emotional reactions to Jesus' suffering. This is a late and dramatic version of the "Man of Sorrows" type. Note the emotional cues - Jesus's bloodied form, alive but with the crucifixion wounds and surrounded by red-eyed weepers. The Band finds the melodrama off-putting, but the idea is to make you empathize with the suffering and sorrow,

Limbourg brothers, Fall of the Rebel Angels from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry f.64v, 1411-1416, tempera on vellum, Condé Museum

It's easy to see where this will head sideways, but the International Gothic was capable of breathtaking beauty because its wealth served logos.

Two pictures trying to trigger opposite reactions, but doing it the same way. Both appeal to pathos - emotion - through sight.

In our how pictures mean post [click for link], we observed that pictures communicate in the same way that we make sense of the physical world in general. We "read" a picture of a person in the same way as a real one. We also noted that the picture isn't real - it's a made-up image that gives whatever it depicts the convincing air of seeing is believing. When Gothic art is described as getting more emotional, it means that the artists art manipulating their pictures to exaggerate the impression that they make. Whether sadness, horror, or beauty.

But it can seem like two different Middle Ages.

Madonna and Child Tabernacle with scenes from the Life of Christ, late 14th century, ivory, Louvre Museum; Röttgen Pietà, 1300-25, painted wood, Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn

And that's a glimpse into how historiography works. You can't recreate the past, and couldn't cover everything in it if you could. Too much happened too long ago. So historians pick a timeframe or some theme and try and tell that particular story. We wrote some posts on historiography some time ago if anyone is interested. They're easy to spot in the epistemology link up above. For here, what matters is that laying down parameters and building models keeps things manageable, but replaces all the countless details with a narrative. The story that the

This is neither good nor bad - it just is. It's the nature of our finite, subjective being-in-time. We negotiate reality through stories and when it comes to the distant past we have a limited record. The problem is when we lose sight of the limits and start pretending the tidily arranged narratives are the same as direct access - as being there. It's why histories have to be read with a critical eye. What story is being told, and how does it line up with other stories around the same subject? Like late Gothic art.

Naddo Ceccarelli, Christ as the Man of Sorrows, c. 1347, oil on panel, The Princely Collections, Liechtenstein

The Man of Sorrows theme seems to have appeared in Italy before spreading north where it developed into it's most melodramatic form. What's significant is that it isn't a scene from the Gospels, but a combination of different moments in one figure. The idea is to concentrate the main elements of the Passion into a single figure to focus the devotions of the faithful.

In this case the big message is Christ's fully human nature that actually dies a human death, and the suffering he endured on our behalf. He's not an "avatar" - he's both God and man, unique in Creation. The Man of Sorrows uses this humanity to trigger an empathetic bond in us.

It bookends with the infancy of Jesus - another emotion-friendly humanized subject that appears to have grown popular in the Gothic era. Just think how many Madonna and Child paintings have been made since the late Middle Ages. Historical narratives support each other when the historians are honest. Historians of religion have traced a growth in emotion-driven religiosity of many different kinds through the closing medieval centuries. The Gothic period of art - ~1150-1500 - is the closing medieval centuries. The Band has shown that that was when the foundations of the modern concept of "Art" were laid down. It's no surprise to see this new devotional spirit expressed in the new popular visual media.

We would have to consider the possibility that the emotional spirituality wasn't new - it's just that there is now art around that shows it - if we were relying on the art as our only evidence. But the intensification and personalization of late medieval religion is something historians of all kinds have noted for a long time. It looks more like parallel developments to us - the drive to get closer to Jesus and the saints and the popularity of art both reflect the desire to make absent things part of sensory, empirical human experience.

Corpus Christi Procession with a Bishop carrying the monstrance under a canopy, 1400-1410, British Library Harley 7026, f.13r,

There's lots of evidence for the growth of interest in different kinds of emotional spirituality. Like the adoration of the consecrated host - believed to be the Real Presence of Christ - was increasingly venerated from the 12th century.

Michael Ostendorfer, Pilgrimage to the Schöne Madonna in Regensburg, 1520, woodcut, Veste Coburg Collections

The Band looked at pilgrimage as something that got more popular too. With lots of encouragement from the Church. Miracle-working statues became objects of veneration and fueled fears of idolatry. See the people genuflecting not to Jesus but to the statue. The pilgrim banner on the steeple also depicts the statue.

Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ , title page. Antwerp, 1505. Woodcut. Utrecht, Museum Catharijneconvent.

The Imitation of Christ is a Christian devotional book written between 1418–1427 for the Devotio Moderna - a forerunner of Protestantism. The most read book of the Middle Ages after the Bible, this stressed an inner alignment with the example of Jesus. It was a personal approach to religion that took Jesus as a kind of mental image. The same kind of motivated looking that something like the Man of Sorrows was supposed to do.

So two historical stories. The blurring of secular and sacred in the world of the Gothic aristocracy and this very different, intensely sincere emotion-driven religiosity.

These are not mutually exclusive. Many elite were deeply religious. Religious hierarchy did blur with the secular. The same skills and often the same artists worked for both. Just two really different historical narratives overlapping in the same material spaces.

Allegretto Nuzi, Madonna and Child and Man of Sorrows Diptych, 1366, tempera and tooled gold on panel, Museum of Art, Philadelphia

This pair sums up the two impulses and how they overlap perfectly. Call them elite aesthetics and religion for want of better terms. The Madonna is maternal if courtly, while the Man of Sorrows is in a grisly state. But both are applied to empathetic religious response. The joy and beauty of birth and motherhood and the pathos and horror of torture and death. The full range of Jesus' humanity.

The important thing to understand is that elite aesthetics and religion aren't opposites. Not like the fake binaries that poseurs and midwits like to pretend define reality. Consider the Hours of Mary of Burgundy - a late Gothic masterpiece for the last independent ruler of Burgundy. Burgundy was one of the great centers of International court culture and Mary the richest woman in Europe, so this book is a masterpiece of elite aesthetics. But it also uses this to visualize the humanity of Jesus in an emotionally engaging way.

Master of Mary of Burgundy, Christ Nailed to the Cross, from Hours of Mary of Burgundy, 1470s, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 1857, f.43v

This picture arranges Jesus' martyrdom as a display for the reader to see. The emphasis is on the body on the cross and the grief of his mother. But the view is through a fine late Gothic arch. Note the prayer book and luxe personal effects at the bottom. Mary is invited to rest on the cushion and picture the scene that her book describes.

It's emotion-driven visual religiosity and elite aesthetics in one picture.

So not binaries, stories. Historical narratives that coexist - diverging and overlapping as they will. Two masters that drift apart and come together depending on circumstance, but set up how art will mean for centuries to come.

We'll look at the emotion-driven religiosity first.

The Man of Sorrows was not the only concentrated devotional picture of this sort. The pietà was another type that took separate aspects of the Passion and concentrated them into a single image for maximum impact.

Pietà from the Lower Rhine region of Germany, 1350-1360, walnut, private

Between this and the Röttgen Pietà above it's easy to see the formula. It's like a bookend to the Madonna and Child - sorrow of death after the joy of birth. There's no Bible story where Mary holds the body of Jesus like a baby after the descent from the Cross. Like the Man of Sorrows, it's an artistic invention designed to stimulate emotion.

This means it's more focused on the feeling than accurate historical storytelling. It's more rhetorical than dialectical.

We've already looked at pilgrimage and the growing cult of the saints and relics that drove it. Relics were stored in lavish and expensive reliquaries - special boxes to give the relics a visual impact worthy of their holy status. But head and other body part reliquaries took the visual messaging to a more personal level.

Reliquary Bust of Saint Yrieix, 1220–40, with later grill, made in Limoges, silver and gilded silver with rock crystal, gems, and glass, Louvre Museum

The expensive materials are still there. Only now they form a human head. Picture this gleaming on the altar and you get a visual suggestion of the supernatural presence of a real saint. More personal, more intense, more emotional

The consecrated Host was another site for emotion-driven devotions that we've mentioned. It makes sense that the real presence of Christ on earth would be a focal point for this drive to draw closer to God personally. The Host is like a relic in that it's visually unimpressive despite being metaphysically vital. The reliquary made up for that with the relics - there were other ways to showcase the Host. All the ritual and apparatus around the altar - including the spectacular altarpieces that began to appear in the 13th century and the luxurious monstrances to hold the Hosts.

There are also many Host miracles - where a Host gives some visual confirmation of its miraculous nature. Usually this is a vision of Jesus in the host or blood coming from it.

Above: King Edward the Confessor and Earl Leofric of Mercia see the face of Christ appear in the Eucharist wafer; below The return of a ring given to a beggar who was John the Baptist in disguise, from a 13th century Domesday Book, around 1240, National Archives, London

The upper picture is a good example of a Host miracle. You can see the priest raise the Host - facing the altar like a fellow worshiper - not facing the congregation like a magus - as an image appears in it. The king and earl serve as witnesses to verify the truth of the story.

The art also includes evidence of how these things were used and appreciated. Pictures showing pictures in use. But we have to be wary of the "interpretations" offered up in modern discourse. Hint: it's fake.

Medieval art is filled with pictures and ideas that are odd to modern viewers - even staunch Christians and defenders of the West. This has led to endless papers by pozzed academics pretending that the spritual messaged in these "weird" images can be explained by fake Postmodern theories. We are interested in understanding what the historical images meant. Anachronistic politicized reinterpretations from materialistic relativists far less intellectually capable than we are are beyond worthless. It's embarrassing to think we once viewed them with a measure of respect.

Put another way, nuns mortifying themselves in the image of Christ may be overzealous, but aren't "anorexic". Anexoria was a collective reaction to a demented and dehumanizing fake upper middle class 20th century media culture masquerading as a fake "condition". Note how it's vanished as an issue in contemporary life.

It's absolute horseshit as a historical model. But the book lives on as an irrelevant testimony to the projected ineptitude of a hack who had no place writing history. Smart enough to string words together, play the academic game and impress other coddled midwits. But too dim to grasp the larger ontological and epistemological framework - to even percieve that these are things. Then even bigger retards "build" off it. Empty busyworkers like this are why the Band argues that "higher education" needs to be leveled, rebuild from the ground up, and given over to legitimate cognitive elites.

What interests us is what we can actually see. Not whether we can validate modern lies, but what can be determined about how far more devout, reality-facing, and morally superior people plugged into the vertical ontology. Like Caterina Vigri, a 15th-century nun who illuminated her breviary with concentrated, personal devotional drawings. The Holy Face and the Holy Infant are two more devotional types. She draws them with the energy of a capable amateur whose main purpose was an emotional religious connection more than meeting the current style.

Caterina Vigri, Christ with adoring nun and swaddled infant Christ, 1452, miniatures in her breviary f.149v, 157r, Bologna, Corpus Domini Monastery

This is art as a form of prayer, but what is revealing is what the prayer is of. Intense, focused, visualizations of the emotionally-engaging elements of the life of Jesus. When we mentioned the development of art and emotion-driven religion as parallel events, this is a good example. The desire to see Jesus and the means to physically visualize him together.

The Infancy and the Holy Face are positive emotional cues. But the same patterns hold with the more gory and sorrowful stream as well. Consider this late German prayer book - its illuminations diagram out the whole process.

The Count of Waldburg kneels before the Man of Sorrows from the Waldburg prayer book, WLB Stuttgart, Cod. brev. 12, f.103r.

Is the Man of Sorrows depicted as actually present or something in the Count's imagination? It doesn't matter - visualization is based on there not being much difference between a picture in a book or painting and in the mind's eye.

The Count's medieval clothes and landscape clash with Jesus' Biblical loincloth. Two distinct moments in time - the Gospels and today - come together. Exactly what happens every time a Christian finds Jesus.

Mary Mediates between the Blessing Man of Sorrows from the Waldburg prayer book, WLB Stuttgart, Cod. brev. 12, f.11v.

This one lays it out. The Man of Sorrows is a composite figure that stands for Jesus' sacrifice. Up top, you see the sacrificial figure as a link between the transcendent Trinity behind the rainbow - note the dove of the Holy Spirit - and material reality. Christ as the link between heaven and earth.

Below, the saving power of that sacrifice is represented by the Man of Sorrows. The intercession of the saints is shown with Mary literally between savior and Christian. The bloody sacrifice opens the way for the saints to guide the worshiper to God.

And you can't overstate the importance of the Holy Blood in this religious climate. Jesus' ascension meant he didn't leave the bodily relics that drove the cults of the saints. His blood was an exception and valued immeasurably. Whether the relic is "authentic" isn't the point. It's the redemption-bringing blood of the savior that is.

Relic of the Holy Blood, Preserved in the Basilica of the Holy Blood, Bruges, Belgium

Famous blood relic venerated in Bruges since its arrival in the 12th century.

The image of the Holy Blood shed by the Man of Sorrows washing away the doom of Original Sin was a powerful one. It turns up in sermons and devotional literature as well as in art. Rarely so graphically as in this Gothic illumination.

Vision of St. Bernard with a Nun, from the Rhineland, 1st half of the 14th century, pen and ink on paper, Schnütgen Museum M 340, Cologne

The crucifix is the quintessential devotional image - the suffering, blood, and death of the actual redemptive sacrifice. Here the physical actions represent spiritual attitudes in a very graphic way. The worshipers embrace the crucifix as a sign of devotional commitment while streams of blood cleanse them. Note how it flows into the world at the bottom but leaves them unstained.

This is not a highly "artistic" image - it's amateurish, though clearly medieval in figure type. But it shows us how the elements of this emotion-driven religiosity worked.

Bonne of Luxembourg was a daughter of the King of Bohemia and married into the French royal family, making her another of those courtly elites. But her prayer book is another source of fascinating images of emotion-driven religious devotions.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?) and workshop, Crucifixion with Christ displaying his side wound to Bonne of Luxembourg and John, Duke of Normandy, folio 328r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349, The Cloisters Collection, New York

It doesn't get much more direct than a crucifix coming to life and pointing to the side wound. The immediate cause of death and source of gouts of blood and water. The two nobles are shown in intense veneration - the gesture shows them what in particular to venerate.

Bonne's prayer book brings us to one of the more inventive examples of emotion-driven devotional images. That's the visual "shorthand" for the Passion, where disembodied gestures and instruments stand for the sufferings of Jesus. One could move attention from one to the next, taking time to meditate on what it means. That in itself isn't weird, but the disembodied side wound is another matter.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, Miniature of Christ’s Side Wound and Instruments of the Passion, folio 331r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349, The Cloisters Collection

This might be the most striking, for the size, placement and color of the wound. One can imagine the amount of Postmodern nonsense generated around the genital look of it. Especially given a female client. The thing with these nonsense interpretations is that they don't even try and deal with the instances where the owner isn't female. Let's put that aside and consider the wonderful strangeness of a disembodied side wound as an object of veneration.

The side wound and the rest of the instruments make a lot more sense when you understand that religious change in the Gothic period. Art grew alongside a widespread desire - a burning desire - to draw closer to God in a human, emotional, personal way.

Compare this to the stern Byzantine Pantokrators and Romanesque judges of the earlier Middle Ages. Art was more closely tied to the Church then but it did exist, and makes for the easiest way to see the change in religious concept.

The Pantokrator is a fascinating theme. It's very old - the oldest panel painting of Jesus that we have is a Pantokrator type. The word translates to Almighty or All-Powerful literally, but it is sometimes given as Ruler of All. In the Septuagint - the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible - and the New Testament it is sometimes used for God. As a picture, it shows Jesus as the hypostasis of the Son - the divine Logos and Creator. This is Jesus as God - the counterpart to the Infancy and Passion images that show his humanity.

Christ Pantokrator, a 6th-century encaustic icon from Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai, Egypt

This is the oldest surviving panel painting of Jesus and has been in the Mount Sinai monastery since it was painted. It's designed to be seen up close, where the lack of background makes it easy to feel a connection with the figure looking right back at you. This is Jesus as divine presence rather than a man from the historical past.

Christ Pantokrator, before 1170, apse mosaic in the Cathedral of Cefalù, Sicily

The Pantokrator becomes a staple of Byzantine domes where he looms over everything. Like this fantastic Norman Sicilian hybrid of Western Gothic architecture and Byzantine mosaic art.

Christ as Pantokrator, 1090-1100, dome mosaic in the Church of the Dormition, Daphni, Greece

The Son can take on a stern, even harsh manner. Perhaps Western Christianity could have used more Pantokrator and less womanish obsession with the "humanity" of Jesus.

The Byzantines did develop a more emotionally-charged art in the Middle Ages as well - it just didn't overlap with the Pantokrator. This painting is commonly shown as an example of the Byzantine emotionalism that influenced European art to varying degrees. This was especially so in Italy.

Lamentation, 1164, fresco, Saint Pantaleimon, Nerezi, Macedonia

The nervous energy looks closer to the European Romanesque than Gothic, but the emotion comes through pretty clearly. The Gothic takes the emotionalism but not the balancing divine authority of the Pantokrator. Jesus is both man and God - movements that have overemphasized one or the other always spiral into error, convergence, and generally secular transcendence as the followers reimagine the divine in their own image.

Closer to home, the most imposing Romanesque depictions of Jesus is the remote cosmic judge in the tympanum sculptures over the main doors of the big churches. The most famous is on the West portal of St. Lazare at Autun, but there were many others. Click for a link for information on these and Romanesque portals in general.

Giselbertus of Autun, Last Judgment, West Portal of St. Lazare at Autun, c. 1120-35

Probably the most famous of them - a rare case where we know the name of the sculptor. See how you're greeted with a reminder of judgment by a transcendent figure. The goal isn't to reassure the unrighteous or make good vibes - it's a reminder of the magnitude of God and what's at stake for us all.

Here's another from a contemporary Romanesque church. The style style is different with more violent movement, but Jesus is just as sternly judgmental and cosmic. In both of them he's also way bigger then everyone else and surrounded by a mandorla like a divine titan.

Narthex Portal from the Church of Ste. Madeleine, Vézelay, 1120-32

There are more, but these are enough to show the difference and how much of a change this Gothic humanizing represents. Emotion-driven or humanizing are vague terms, but you can see from the examples that this new impulse expresses itself in so many ways that we need to be vague. And compared to the Romanesque examples, all of them - despite their different messages or perspectives - use amplified emotional rhetoric. After that point, they have to be treated differently, but if we're looking for a big shift in religious attitude, this is it. And when we put this next to the religious changes that other historians have note, it all fits.

Now when you see something like this, with its images of suffering among disconnected objects, you know what it means.

Passional of Abbess Kunigunde, parchment, 1312 to 1321. Bohemia, early Luxembourg court workshop Prague, The National Library of the Czech republic

It's a shorthand picture of the Passion, with the stages and instruments of Jesus' death laid out for you to work through. The Holy Face at the top and the disembodied side wound next to the Man of Sorrows on the crucifix.

Or this Man of Sorrows/Passion altarpiece from Italy.

Master of the Strauss Madonna, Man of Sorrows and Saints, 1380-90, S. Romolo a Valiana, Pratovecchio

The gory or disturbing Gothic style was a practical way to fire up emotions pictorially. Because we "read" pictures and statues the same way as visual experiences in the real world, we react emotionally to a suffering figure. We empathize and in doing so, personalize. At which point, emotional connection is established and the picture has achieved it's main purpose. And once in the right mind set, it depicts a story or figure to meditate on.

Crucifix, around 1300, painted wood, Chapelle du Dévôt-Christ, Perpignan Cathedral

That explains figures like this tortured crucifix. The broken body is marked by such an extremity of suffering that it is difficult to look at even now. And that's the point - that difficulty is an emotional revulsion. Meditating on that opens the path to commensurate feelings of pity and gratitude for what he endured.

That's what we mean when we talk about the emotion-driven religious aspect of Gothic art. What it really looks like is an art of extreme empathy, with exaggerated emotional cues. It's human nature that violent or disturbing imagery is hard to ignore and stays with you afterwards - this art uses that to power a religious message. The suffering is in the stories. But that ability to show things that make meaning like the real world gives a visceral punch that words can't match.

William Beasley, Worth 1000 Words, 2011, mixed media

Art can be more rhetorical or dialectical in focus, but the nature of pictures means that even the most logical message with have a large rhetorical component. The emotional Gothic isn't logical messaging.

Suffering may be the most raw stimulus, but beauty also works rhetorically on the emotions to create the right psychic state. This is where the beauty associated with the International Gothic style - what we called elite aesthetics - overlap with the emotion-driven religion despite looking different and describing different domains. Remember - these aren't opposites, they're tendencies. The elite can be religious. In fact, it's religious aristocrats that start bringing elite aesthetic beauty to subjects of emotion-driven religion.

Remember the overlapping of secular and sacred in the world of late Gothic aristocrats?

The Master of Catherine of Cleves, Deathbed and Souls Tormented in Purgatory from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, Netherlands, Utrecht, ca. 1440

Horror and beauty may be opposite on one level, but both make rhetorical appeals to the emotions. This is why we consider them together.

Now for the International Gothic

At this point, we're less concerned with what art is as much as what it is showing us. Religious emotion is one reveal. Another is the birth of an international order.

We looked at the rise of the aristocracy and court culture in earlier posts [click for the main one]. This is where we find a precursor to today's conflict between national cultures and satanic globalism. The easiest way to put it is that the nobility form a separate culture from the nations they rule over. A culture with more in common with foreign courts than local people. The International Gothic is the courtly version of the Gothic style so it is much more consistent than the different national Gothics we saw in the last few posts. Here are some of the main court centers where this art grew up.

Note the size of Poland and the swath of land under rule of the Teutonic Knights. Christendom used to be Christian.

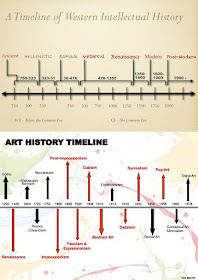

The International Gothic creates problems for historical analysis because it doesn't fit with the official timelines. Timelines have to eliminate all kinds of details and complications for simplicity and clarity, but these details have more to them than the usual stuff dropped from a summary.

First is the nonsensical Progress! distinction between "Middle Ages" and "Renaissance" as moving from an age of faith to and age of humanism and eventually to an age of satanic materialism. The late Gothic courts complicate that transition - bringing secular glory and materialism together with religious devotion and spiritual beauty. It's a combination of the mature Gothic and changing Europe that is contemporary with and more consistent with the Perpendicular and Flamboyant in architecture.

This is an opportunity to think about how "periods" are created. We've seen how different areas are different - any period has to smooth over regional variations. The problem is when the historians making the compromises aren't trying to come up with the summary that best fits the known facts but are using it to impose an agenda on the facts. Like old friend Progress!.

The art one is the worst. The beast system expects us to believe in a concept of "art history" where the Gothic, Constructivism and Dadaism are all equivalent. If by now you can't see how inherently fake and dyscivic this is. There's no progress in that dissolution.

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the medieval court culture of the European aristocracy had reached a mature form. One that the general improvements in prosperity and technology made very wealthy. Remember - aristocrats are a parasite class. What nominal leadership or inspiration they provide doesn't justify their cost. The richer the host, the more it can afford to give the parasite. And the foundation of aristocratic power and wealth was land ownership - as agricultural technology improved, the land became more productive and increased population made it more valuable. The result - a court culture of considerable comfort and luxury. Especially compared to the earlier Middle Ages. Click for a post on the late medieval court culture and nonsense chivalry.

Noble privilige was rigorously maintained by limiting marriage in most cases to other blue bloods. A simple numbers game meant high nobility had to marry foreign peers. Family ties and diplomacy were the prime ways that an internationalist aristocratic culture developed "over" the national ones. These aren't today's satanic globalists. Medieval nobles acted in the name of the lands they ruled and had no interest in one world evil. We're just looking at a culture pattern - a divergence of globalist court and national culture that is a precondition for the slow evolution of modern elite globalism.

Jean Colombe. Superlion from the Hours of Louis de Laval, around 1480, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Ms. Lat. 920, f.29v

The explosive growth of art in the late Middle Ages means that we can see this courtly internationalism with our own eyes. The development of heraldry was a way of classifying and keeping track of aristocratic blood lines. Louis de Laval's lineage is shown here is the form of a mythic beast. Note the Gothic castle in the background. Click for a link to piece on this book.

The term International Gothic refers specifically to art - the consistent appearance in different places is what the international court culture looks like.

This is art at a crossroads. The elites were Christian and their elite art included Christian themes. So their art had the beauty and logos that makes International Gothic images still popular today. But it was also did so in the service of elites who ultimately inverted Christendom. It's easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man to enter heaven as the Bible says. It's not money qua money that is inherently evil - it's the lust that it engenders and the resources to feed appetites that it gives that make evil come easy.

The Band's working definition of art is techne and episteme - technical skill and logos. Click for the summary post. Technical skill has no moral alignment but logos is moral alignment. It's the moral reasoning that extends through the Son to Truth.

Here's the post where we introduce these terms and the post where we find the perfect overlap with the ontological hierarchy.

Art is hard to define because it's ontologically composite - a visualization of invisible truths in material form. When technical skill bends away from logos and truth, beauty is replaced with allure - sensory appeal. Cotton candy. Allure as an end in itself is like money. Appealing appetitively but a materialist snare in the end.

Bringing us to the topic of pictorial rhetoric. Art is inherently rhetorical because it includes unconscious reactions to things that aren't real. But there are degrees of dialectical content as well. Art that conveys truthful messages for the right reasons is conveying logos to the intellect, while empty sensory pleasure sends pathos to the emotions. It's ambivalent and can easily be jacked for nefarious ends.

The International Gothic is when these possibilities become visible, but are still undecided. That's why part I of this post called it a crossroads. Art was coming into existence in a serious way - it didn't have institutes or expansive structures. The path was not fixed. Does the refined beauty morph into materialist self-indulgence or does it continue to shine logos into the world?

Tom McGrath, The Curse of Mindset, 2011, digital art

We know the answer, but it is important to see why. If we want to restore beauty to the culture of the future.

The Italian Gothic post left off with Sienese painter Simone Martini and the papal court of Avignon. This was where he passed his elegant version of Duccio's art to the Gothic masters from the northern European centers.

Simone Martini, Angel of The Annunciation, 1333, tempera on wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Simone Martini, Virgin of The Annunciation, 1333, tempera on wood, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

It didn't take long for this to spread around the courts of Europe. Manuscripts remain popular, but Italian-style panel painting also takes off. Including big public altarpieces and smaller devotional pictures for personal use. The rest of this post will look at the main courts and the late Gothic art that came out of them. This will give a nice overview of the style and set up an alternative counterpoint to the Renaissance than we see in the official timelines. The International Gothic is often called "Northern Renaissance Art" because it appears when the Italian Renaissance is supposedly midwifing the birth of secular transcendence. Let's see what it really is.

We're going to see some magnificent work. Be attentive to the overall similarities - especially the presence of aristocratic courtly values. If you can spot these, you've got the International Gothic.

Burgundy was one of the great late Gothic courts. Under the Valois Dukes, it was prosperous, culturally advanced, and a hotbed of art. The capital in Dijon was where the ludicrous late medieval "chivalry" was closest to an official ethos, but Flanders - along with central Italy - was one of Europe's most innovative art centers.

The map shows the feudal aristocratic nature of Burgundy - a patchwork of tiny states from Savoy to Holland. The Valois dukes were related to the French royal family - it's easy to see how art and culture jumped around so easily when you look at this.

Jean Malouel (c. 1365-1416) was an early International panel painter and court artist for Burgundian Dukes Philip the Bold and John the Fearless. It's an example of the closeness of these courts that Malouel is Netherlandish but sometimes called French. The great thing about Malouel is that he paints subjects that belong to the emotion-driven religion class in an courtly late Gothic style.

Attributed to Jean Malouel, Large Round Pietà, between 1380-1404, tempera and gold on oak panel, Louvre Museum

Like a pietà-Trinity hybrid with the connection between mother and son and the side wound as central focal points.

Jesus is dead, but not battered and disfigured like earlier pietàs. There's an odd attractiveness to his unblemished form, and even the blood creates a striking contrast against his white skin. Aestheticized horror is one of the stranger aspects of late Gothic art. It looks to us like it's trying to combine the emotion-inducing suffering and the beauty of the religious truth it represents.

His last work - an altarpiece for the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis that we saw in earlier posts - nails the combination. It was unfinished when he died, but a painter named Henri Bellechose finished it in a similar style. Once again Crucifix and Trinity team up to show the metaphysical connection between the suffering humanity of the sacrifice and the glory of God. This one includes scenes from the martyrdom of St. Denis in the 3rd century. Yet somehow he happens to be wearing the lilies of France.

Henri Bellechose and Jean Malouel, Saint Denis Altarpiece, 1416, tempera, gold and panel on canvas, Louvre Museum

Aristocratic piety, secular honors, and moving deaths. Art at the crossroads.

The Dukes of Burgundy used art to give their court status and luxury to match any in Europe. The Dijon Altarpiece - aka the Champmol Altarpiece - captures this in several ways. It's also a chance to look at a common northern European form - the triptych altarpiece. These were like boxes with painted hinged doors and another image inside. When closed, the painting on the doors is visible, but they were opened to reveal the image within. Whether open or closed depended on the context. Here it is closed - look at the gossamer Gothic interiors where the elegant characters interact. Here's a piece by an art historian,

Melchior Broederlam, exterior panels for the Crucifixion Altarpiece for the Chartreuse de Champmol (Dijon Altarpiece), 1398, tempera on wood, Musée des Beaux Arts, Dijon

The Dijon altarpiece was commissioned by Philip the Bold for the Chartreuse de Champmol - what was supposed to be the duke's answer to the royal abbey/necropolis of Saint-Denis in France. The subject matter focuses on a familiar Gothic subject - the emotionally stimulating humanity of Christ - but does so with courtly richness.

The courtly richness really kicks in when you open it though.

Jacques de Baerze, interior of the Crucifixion Altarpiece for the Chartreuse de Champmol (Dijon Altarpiece), 1393-99, gilded and painted wood, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon

The inside is splendid. Carved and gilded scenes of the passion and figures of saints within the most spectacular Flamboyant Gothic setting. Emotional subjects and courtly status in one incredible package.

Here's a closer look. The detail is remarkable.

The Limbourg brothers - Herman, Paul, and Johan (active from around 1385 – 1416) - were probably the greatest of the Medieval miniaturists. They were from the Netherlands, so were Burgundian citizens, but they plied their International Gothic art in France as well. Their most famous work - the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry - was painted for a French nobleman.

Limbourg brothers, January, from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1412 and 1416 or around 1440, illumination on vellum, Condé Museum Ms. 65, f.9v.

The Duke of Berry and his court. The best-known part of the Très Riches Heures are the labors of the months or calendar pages. Each corresponds to a month of the year and follows a formula. A large miniature of the activity traditionally associated with that month and the relevant zodiac sign above. The Labors of the Months was a standard medieval theme, but the Limbourgs turn them into full-blown paintings.

The Duke starts the book and the year with his New Year's generosity. This symbolic labor shows the generosity and responsibility that makes him a good ruler. Whether this was true is unclear, though his duchy was prosperous. Note the luxurious feel of the court as well as the "knightly" tournament in the background. It's a prayer book, but this is aristocratic nonsense world.

The Band has used pictures from this incredible manuscript before - like January up above, it's full of glimpses into 15th-century life. But looking at closely reveals just how much of a masterpiece it is. Instead of looking at a couple of different Limbourg pictures, we are going to take a little space and showcase this special volume. There isn't a better example we've come across of that International Gothic splendor. This manuscript as much as anything defines the period style. Here is a complete set of scans of the whole thing. Below are the 12 calendar pages. They're filled with exquisite scenes and remember - blue is the most expensive of colors by far.

The overall gist is consistent - aristocratic luxury and a fertile orderly countryside in elegant International Gothic style. The differences are in the activity and the anecdotal details that gives each its charm. Here are two more - one showing an aristocratic betrothal and the other harvest time - in scenic countryside with fairytale castles. What comes through is the socially integrated vision - you can see boaters in the background of the aristocrats and a noblewoman heading into the castle behind the harvesters.

Remember - this was painted for the duke. The Limbourgs didn't poll the peasantry to determine their real feelings. But the idea that the duke would promote such a localized social vision shows the difference between this culture and satanic globalism. Parallel cultures around noble status had clearly formed, but the elite still viewed the nation as an asset not an enemy. There's still logos - hence the beauty.

Limbourg brothers, April, from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1412 and 1416 or around 1440, illumination on vellum, Condé Museum Ms. 65, f.4v.

Limbourg brothers or Barthélemy d'Eyck, September, from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1412 and 1416 or around 1440, illumination on vellum, Condé Museum Ms. 65, f.9v.

Shades of aristocratic parasitism are also visible when you look bast the surface impression of harmony. The harvesters don't seem impovrished but they are working, and anyone who's done it knows farm work is tiring. The woman on the lower left in the gothic curving pose is taking a break. But for the aristocrats, the land is more like a park. A pleasant setting for social activity or an estate home, but there'll be no labor. The closest they'd get would be hunting or some other sporting activity - physical effort, but for enjoyment not need. And yes, there were the occasional aristocrats that worked their land or built things themselves, but they're outliers and did so by choice, not necessity.

The calendar pages are only a portion of the art treasures in this book.

Limbourg brothers, The Nativity from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1411 and 1416, tempera on vellum, Condé Museum Ms. 65, f.44v

There are Biblical scenes from both Testaments, including this Nativity with the annunciation to the shepherds in the background. The setting is humble but the Mary and Joseph appear courtly and God the Father presides over it all like the ultimate king.

Emotion-driven Gothic subjects include pathos and suffering, and the Très Riches Heures include them with the same courtly flair. This page isn't by the Limbourgs - all three of them and the Duke of Berry died in 1416. Historians aren't sure of what, but the assumption is some sort of plague. The manuscript wasn't completely finished, and other artists added to it over the following decades. Jean Colombe was the last of these - his Man of Sorrows is an example of a more painful subject and Colombe's version of late International Gothic.

Jean Colombe, The Man of Sorrows from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1485 and 1486, tempera on vellum, Condé Museum Ms.65, f.75r

Colombe shows the impact of the Renaissance in his deep and atmospheric landscape setting and classical nude figures at the bottom. He also frames his scenes with Gothic architecture while the Limbourgs preferred a simpler set-up.

The Man of Sorrows is a familiar figure though.

There are author pages for the Evangelists and some of the Old Testament prophets. These combine dramatic figures, symbolic settings, and courtly elegance.

Limbourg brothers, St. John on Patmos, from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1411 and 1416, tempera on vellum, Condé Museum Ms.65, f.17

The perspective of the saints converging on God is not optically "accurate" but is an eye-catcher. Angels transmit the message to John while his symbol the eagle attends.

There are afterlife panels, like this powerful scene of Hell. The Limbourgs capture an important aspect of the infernal state - Satan torments the damned, but he also is in eternal torment.

Limbourg brothers, Hell from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1411 and 1416, tempera on vellum, Condé Museum Ms.65, f.108r

Satan is the prototype gamma - the secret king that deludes himself into believing his wishes and desires supersede reality. They don't, leading to spiraling lies and toxicity, to self and others. Better to rule in Hell than serve in Heaven could be a gamma motto, but all the bold lies can't change Hell from a place of well hellish torment.

Rejection of reality leads to agony that drives doubling down on the rejection leads to more agony that drives doubling down... The only way out of this ontological spiral into non-existence is living in truth.

One last look at the Anatomical Man - an International Gothic image of the idea of the microcosm - that man is a miniature version of the cosmos. A nude figure in something close to a classical contrapposto stands in the middle of a mandorla marked by the zodiac. Together, these represent man and the cosmos. Note how the zodiac signs superimpose on different parts of the body. This represents the connection between the two.

Limbourg brothers, Anatomical Man, from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, between 1411 and 1416, tempera on vellum, Condé Museum

The arms of the Duke of Berry are in the top corners. Note the lilies of France on his arms as well - he was brother to the French king and had the right to that heraldry. Latin inscriptions describing the properties of each zodiac sign according to the four complexions (hot, cold, wet or dry), the four temperaments (choleric, melancholic, sanguine and phlegmatic), the four cardinal points and gender. This is a good example of the medieval tendency to systematize and symbolize almost everything.

We could go on - it's such a great book. But this post is getting long and we don't wan't to have to break off a part three. But it's probably the best look at the International Gothic in one place that you'll find - peruse the link to the scans if you'd like to explore further.

Burgundian sculpture was also quite advanced. In an earlier post, we saw the tombs of the dukes, including the work of Court sculptor Claus Sluter. Too bad there isn't more time - Sluter's work has a real physical and psychic weight that draws comparisons to the painting of Giotto in Italy a century earlier.

Claus Sluter, Well of Moses, 1395 -1403, Centre Hospitalier La Chartreuse, Dijon, France

Sluter's most famous work - a well with Prophets supporting a lost Crucifixion scene above. Just as the Old Testament supports the new. Infogalactic describes Sluter's style as "combining the elegance of International Gothic with a northern realism, but with a monumental quality unusual in either".

Here are King David and the Prophet Jeremiah with he color coming through and their scrolls are more visible. They're like manuscript figures come to life, but with a massive gravitas that the elegant International Gothic usually skips.

Like Giotto, Sluter is a bit of an outlier for his time and has most of his impact later.

Our historical skim is limited to historically important developments, so there's one last Burgundian International Gothic thing to consider. This is the beginning of a wholesale artistic transformation that historians call the Northern Renaissance - another chapter in the art of the West. As a concept the Northern Renaissance is historiographically shaky. At a glance, it seems like historians projecting the idea of the Italian Renaissance onto artistic changes in the Netherlands. Dutch painters used oil paint to create a new kind of panel painting in the early 1400s that relates to the International Gothic but with more emphasis on realism.

The artist most associated with this is the Flemish painter Jan van Eyck (circa 1390 –1441) and his family workshop. And since Flanders was under Burgundian rule, these painters worked for court clients. But what makes this different from court art is that panel painting in the Flemish cities was driven by the new merchant class. A hint of the financialized world to come.

Hubert van Eyck and Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece, 1432, oil on wood, Saint Bavo Cathedral

To the Band's eyes, there really was something new going on with the Dutch artists. The paintings are Gothic in theme and overall style, but the realism is eye-opening when you've gotten used to Gothic art. Like this hybrid God the Father-God the Son with a papal tiara. This regal figure and the queenly Mary show the International Gothic roots of this new style. And the lower panels show much more developed landscape skill than the preceding generation, like say the Limbourgs.

The drivers have little to do with the ideology of Renaissance humanism beyond attention to the appearance of the visible world. The subject matter and purpose are very much rooted in a medieval emotion-driven religiosity. Note Mary's prayer book - she's a devout queen.

The historiographic problem with the Northern Renaissance - it assumes a consistency with Italian Renaissance ideal that "the North" - Italy either, for that matter - really had. The Band's high-altitude perspective has made us aware of some fundamental problems with the "discourse" that those trapped in it seem unable to see. The Renaissance as it appears in art surveys seems a poor fit with historical and metaphysical realities. This means the art posts will continue to be long like this one as we try and map out what really happened and what it means for the cultural heritage of the West.

It appears that reconnecting with our culture will require identifying what that culture actually is.

Workshop of Jan van Eyck, Requiem Mass, funeral in a church, from the Très Belles Heures de Notre Dame de Jean de Berry, between 1420 and 1430, illumination on parchment, Turin, Museo civico d'arte antica, Turin-Milan missal, f.11

Van Eyck's shop applying advanced realism to another of the Duke of Berry's lavish book collection. The Très Riches Heures may be the most accomplished, but that's not throwing shade on the other 9s and 10s in his collection like this one.

The realism is in the perspective of the space. An angled interior is pretty advanced drafting for the 1420s. Earlier Gothic posts noted that handling of space is something historians look at a sign of growing Gothic realism. This is that at its International Gothic maturity.

This page isn't the most impressive in the Très Belles Heures de Notre Dame, but it shows the link between courtly book painting and the new panel pictures. Which is International Gothic and which is "Northern Renaissance"? The answer is both or neither - these are just categories that sink or swim with how well they map onto reality.

The difference is context. The manuscript appears in the court environment associated with the Gothic. This painting was probably the wing of an altarpiece like the Ghent Altarpiece up above.

Large beautiful queenly Madonna in an incredibly realistic church interior. She's realistic too but too big for the setting, meaning she's probably a spiritual vision. Here's a link on Van Eyck and the symbolism and function of this magic realism for emotion-driven religious devotion. Visualize the holy beauty of Mary and Jesus in your real church.

But don't miss the huge historical pivot

The aristocratic image of Holiness that grew up in court circles is transferred to an altarpiece for the wider public.

Aristocrats represented Madonna as a queen - that is, in their own terms. When that vision was projected onto the people, they get a Madonna in someone else's terms. No wonder church and crown get conflated in the public imagination.

And we get to see it.

Put the Madonna in the Church next to the Très Belles Heures and the architecture is nearly the same. The connection between the International Gothic and the Northern Renaissance associated with Van Eyck is visible

Historiography is so much more important than it gets credit for because it sets how history will be told. There are earlier posts that explore the similarities between history and storytelling - historiography determines what kind of story gets told. Get this wrong and even the best facts don't really matter. If you think of Van Eyck as a revolutionary realist who moves the material human world to the center of his paintings, the magical parts of his realism are odd. But when you realize that the idea of "revolutionary art" is an anachronism and that the Gothic had been moving to greater realism for centuries it's less mysterious.

This art takes tendencies that were present in the Gothic - realism, visualization, emotion-driven devotion - and develops them in a particular direction. Eventually the realism will become the point and the other Gothic tendencies go by the wayside. But that's a story for another post. For now, take a good look at this painting. Note the realism and try and describe what's happening.

Jan van Eyck, Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele, Saint George and Saint Donatian, completed 1436, oil on oak panel, 141 x 176.5 cm (including frame). Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Everyone seems so real, but the Canon and the saints clearly belong to different orders of beings. The real tell is that van der Paele doesn't look at anyone. We're getting a highly realistic image of his religious imagination. Or state of mind at least. It isn't clear if he's picturing this or if they symbolize

Van Eyck's detail extends to the shadows and distortions of the Canon's glasses!

Here's a long piece discussing optical symbolism in Van Eyck and the importance of the glasses in this painting. It's typical of the spray of references that hovers over these sorts of paintings. Understandable given how vivid and obviously full of symbolism that they appear to be. It can be a bit of a slog, but it also helps think though some of the cultural references and associations.

It's the interplay of realism, symbolism, devotion, and metaphysics that's so hard for modern minds to wrap around. The idea that material realism could function associativity as a sign for higher Logos is hardly a puzzler for an ontologically awake Christian. The confusion comes from the historiography - the fake beast system concept of Art! needs this realism to be a step away from the medieval world view. The beginning of the road to realism that would eventually be replaced by modernism. But these distinctions don't exist for Van Eyck. Spiritually, he is a Gothic painter and a master in combining logos and techne. He's an artist of the West.

Just look at this illumination from a later Burgundian prayer book - this one from the last of the Valois Dynasty. Here, the Duchess is simultaneously shown reading her prayer book and venerating a Madonna inside a church that resembles Van Eyck's from before.

Master of the Hours of Mary of Burgundy, The Book of Hours of Maria of Burgundy, between 1467 and 1480, illumination on parchment, Austrian National Library Codex Vindobonensis 1857

This makes clear what the Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele implies - the art is visualizing the same spiritual truths that the viewer is supposed to. The realistic appeal of the International Gothic serves the emotion-driven piety by bringing the imagination to colorful life.

That will do for Burgundy. The tour now makes a quick stop in France, where ties ties to the Burgundians and the influence of nearby Flanders made the courts hotbeds of International Gothic art. Not just the king, but others like the Duke of Berry in his ducal court in Bourges.

We see a similar relationship between courtly manuscripts and the newer panel paintings. Jacquemart de Hesdin (1355-1414) was an an early French painter in the International Gothic Style and was in the Duke's service from 1384 until 1414.

Jacquemart de Hesdin, Penitent David from the Grandes Heures de Jean de Berry, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica Latin 919 f.45

Another of the Duke of Berry's fine manuscripts. Click for a scan of the whole thing.

Heavyset, almost like Sluter, with a strong royal flavor. Luxurious color and a spatially coherent landscape scene. Note the shield with the lilies of France in the corners. The idea is to connect the Biblical kingship to the French royal family - that the duke belonged to.

France doesn't have a painter as innovative or with as strong a personality as Van Eyck, but Flemish influence hits panel painting there as well. Here's a splendid piece that combines luxurious courtly International Gothic and the enhanced realism of the new art. This further complicates the idea of Renaissance since it really doesn't fit the Italian or Northern versions. Classical symmetry, Flemish realism, and International Gothic luxury. Just look at the textures...

Enguerrand de Quarton, The Coronation of the Virgin, 1454, oil on canvas, Pierre de Luxembourg Museum

This is a hard painting to classify. Its very realistic in detail and finish, but the content is like a theological diagram and the arrangement is visionary. Technically, the fullness of the color and detail was made possible by oil paint - probably the biggest contribution of the Van Eyck "revolution". Oil can do light effects, color gradients, and fine detail better than the temperas, inks, and fresco that dominated medieval art until now. If panel painting was going to move to the center of the art world, it needed a medium that could outshine all the others with what it could do. Oil paint was that medium.

Jean Fouquet (1420-81) was a painter and manuscript illuminator in the French court between the International Gothic and whatever that Northern Renaissance was. His Melun Diptych brings together the things we've considered in this post and captures the weirdness of late medieval art. Diptychs are a pair of matched paintings. The two are separate, but are designed together to relate in some way. This one was painted for King Charles VII's treasurer Étienne Chevalier - a wealthy and powerful figure in the court.

Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych: Étienne Chevalier presented by St. Stephen, 1452-1455, Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts

See how the features we've identified work together

✅ Oil painting with realism and rich texture. The face doesn't make Chevalier look ideal or heroic - it's an honest portrait.

✅ Luxurious court finery and setting - the marble paneling shows the new Renaissance taste for Classical style, but it's still high cost.

✅ Tangible, emotion-driven religious visualization. Like Van Eyck's subjects, Chevalier is accompanied by a shockingly real saint holding one of the rocks that martyred him.

International Gothic luxury, Van Eyck-style realism, and late medieval piety. See the crossroads?

Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych: Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels, 1452-1455, Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts

The other half - a Madonna and Child and presumably the subject of Chevalier's devotion - has to be near the top of the list of weird wonders of medieval art. The de Quarton Coronation of the Virgin is the closest the Band has seen to the intense colors. The rubbery children and pneumatic Madonna seem unique.

The Madonna lactans or nursing Madonna was common in late medieval art. Ties in to the whole human aspect of Jesus - what's more essentially human than a nursing baby? This is different. Mary is believed to be a portrait of royal mistress Agnès Sorel. Her hairstyle and crown show the court style of "the most beautiful woman in the world".

See the way the elite aesthetics and intrigues of the court and the green checkmark features come together? There's no way to separate them. Or even allocate percentage importance. When we say art lets us share experiences with the past, this is what we mean. We get a slice of all the complexity and contradictions of the late medieval court. We call it a crossroads, but we doubt they saw it that way at the time. Crossroads implies clearly defined choices, and this is a lot less clear cut.

What is Chevalier devoted to?

The German International Gothic will be familiar to us now. Master Bertram is an innovator of the style - as in his impressive Grabow Altarpiece. This is almost like a picture Bible with a string of scenes from Genesis

Master Bertram, Grabow Altarpiece, 1379 and 1383, tempera on wood, Kunsthalle Hamburg

The late German Gothic has a flexible attitude towards media, combining painting and sculpture in composite altarpieces. The modern concept of art is based on keeping media separate, so these can be hard to categorize.

Master Bertram, Landkirchener Retabel, around 1380. painting and gilding on oak, Gottorp Castle, Schleswig, Germany

The bottom right panel of the central part shows a descent from the cross or entombment with the features of a pieta.

Gold and blue colors and courtly manner with one of the heart-wrenching scenes of emotion-driven piety.

The late German Gothic also blurs the line between elite aesthetics of beauty and the horror side of emotion-driven piety more than other regions. Aestheticizing, even eroticizing suffering is more complex emotional manipulation than one or the other. What does a modern viewer make of Master Francke?

Master Francke, Man of Sorrows, tempera on panel, circa 1430, Kunsthalle Hamburg

The suffering is clear, but there is a unsettling aestheticism here. The pristine white skin, lurid reds of blood and shroud, and the Gothic angels bring incongruous beauty. A satanic Fraudian (sic) would blather on about eros, thanatos, and other myths that they don't understand very well.

The reality has more to do with the metaphysical Beauty in Jesus' sacrifice

This doesn't mean that the Germans didn't favor more conventional International Gothic beauty - this Madonna by Stefan Lochner is cut from the same cloth as all the other heavenly queens that we've seen

.Stefan Lochner, Madonna of the Rose Bower, 1448, color on wood, Wallraf–Richartz Museum

The delicacy and graceful manner, expensive blue and gold coloring, royal crown and courtly swept back hairstyle, here in a lovely garden. It's a German version on that International Gothic luxuriant beauty.

German woodcarving also develops into an elaborate late Gothic form but this unique and not part of a pan-European movement. And why is that?

Because it isn't courtly. The hypothesis is that the International Gothic shows us a forerunner of globalism because it reveals a parallel internationalist culture outside the organic natural ones. The sign is the consistency between courts regardless where they are. German limewood carving was not an international court phenomenon. It was a local development that expressed logos in a local way. The logos is universal - following the analogy, the art shows familiar themes and stylistics. But the medium is material-level circumstantial.

Tilman Riemenschneider, Marienaltar (Altar of the Virgin Mary), 1505-1508, limewood, Herrgottskirche, Creglingen

Reimenschnider is probably the best of the German limewood carvers of the late Gothic. Some call him "Renaissance" for similar reasons to Van Eyck only Reimenschnider is later still - this is from the era of the Sistine Chapel and Mona Lisa. But a closer look shows how different this art is from the classicism and humanism of the High Renaissance.

What they are are masterpieces. The intricacy of the carving matches any Flamboyant Gothic stonework or International Gothic illumination.

The woodcarving is astounnding in techne. It's refined Gothic skill on par with any of the wonders we've looked at. Riemenschneider uses minimal paint - many of the limewood artists painted their carvings - like Master Bertram's Landkirchener. Limiting the coloring to stains and varnishes lets the carver's skill shine through.

The top of the Marienaltar is a marvel of detail. Some of the most intricate late Gothic decorative sculpture anywhere. Figures occupy a wonderland of spirals, vines, pinnacles, and other Gothic architectural features. Note the flat ogee arches - a late Rayonnant feature.

Riemenschneider doesn't paint his carvings but he does conceive of them like painted altarpieces. The Marienaltar is a polyptych - it's a "box" with wing doors that open up to show the main scene. Here, the main scene is carved as if free-standing and the doors decorated with relief sculptures.

The inside of the right door includes a Nativity scene with an intricate bit of vine work to connect the scene to the rest of the altar.

A Marian altar is a sign of the late medieval cult of the Virgin - part of the emotion-driven religious environment of the era. Mary's motherhood is one of those subjects that puts the humanity of Jesus front and center. But the style is graceful late Gothic beauty.

The main part of the altar shows the Assumption of the Virgin - a popular subject that shows Mary ascending from her tomb as the Apostles look on. The scenes from her life in the doors are in relief but this miracle is full-figure.

Back to the historiography. Why would there be pressure to classify this as some sort of Renaissance? The reason may be hard to believe for those still under the illusion that academic history is dedicated to the pursuit of pure knowledge. It isn't. It's not the material facts in this case - but the interpretation. When historians started to seriously consider the visual arts in the 19th century, they followed what was more or less Renaissance historiography. That is, the idea that the arts of classical antiquity were supreme, the Middle Ages were dark - crappy and culturally backward, and the Renaissance restored civilization. The way this myth echoes was a major reason for the amount of time the Band has spent on Gothic art and architecture. Because the Dark Ages-Renaissance model is a false picture.

For one thing, it misses the beginnings of a techne-episteme based Western art that we've just watched unfold. And the model assumed Renaissance preeminence, so medieval studies spent much of their formative years justifying itself in Renaissance terms. Showing that the Italian Renaissance wasn't so special. The problem is that it accepted the historiographic terms.

So you get general renaissances, Carolingian renaissances, Byzantine renaissances, 12th century renaissances, and countless others.

The irony is that while medievalists were racing to prove their own renaissance bona fides, the renaissance is a largely bogus construct.

The concept of Renaissance that "brights" cling to is a fiction of 15th century humanists and 19th century romantics. This is triggering to NPCs and bugmen. The nature of modern education means accepting textbook learning from narrative engineers. How many people who think they're culturally invested in the notion of the Renaissance have ever read a Renaissance book? If you don't know the literature, whose hill are you really dying on? And if it didn't happen, why care?

It's not a question of whether there were classical revivals before 15th century Italy. It's that the classical supremacy-Dark Age-Renaissance model of history is abject garbage. Secular transcendent inversion spun by liars to separate humanity from it's divine birthright. That's not to say the Renaissance isn't historically real. There is an identifiable set of ripples on the Italian timeline that corresponds to a Renaissance period. It just isn't what they told you it was.

Andrea Mantegna, The court of Mantua, finished 1474, fresco, Palazzo Ducale, Mantua.

But they did get fancy pants.

Michael Baxandall, The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, Yale University Press, 1982

So when we see Riemenschneider and his contemporaries on the cover of a book like this, it's ok to wonder what this Gothic vision has to do with the Renaissance worlds of Michelangelo, Leonardo, and the Florentine humanists. Because the answer is very little.

It does however give that academic Renaissance rub to fields that were otherwise dismissed as backwards or medieval.

Look at the close-up of the Marienaltar and think of the last few Gothic posts. There's nothing to be gained by pretending that this expresses the secular transcendence of Renaissance humanism. It doesn't. It's the late flowering of medieval German art and devotion before vain materialism began pulling our eyes away from God.

Before leaving Germany and the limewood carvers, here's one example of a contemporary of Riemenschneider who did paint his sculpture. Veit Stoss was also successful and rated near the top of his craft. Here's his version of a Marian theme - an Annunciation - to show the difference the paint makes. This is Gothic beauty moved outside the court setting and applied to the desire for a more emotionally connected religious devotion.

Veit Stoss, The Annunciation, 1517-1518, painted limewood, Lorenzkirche, Nuremberg, Germany

An International Gothic apparition hanging in the stained glass light of a church. This is courtly beauty applied to the rhetoric of emotion-driven worship. It's effective.

It's also another way for the secular and sacred to blur in the eyes of onlookers.

Lingering in central Europe brings us to Bohemia - Prague was another court hub of the International Gothic. It wasn't a large kingdom, but the Holy Roman Empire made it a major cultural center. This took off in 1348, when Charles IV founded the University of Prague and drew artists and craftsmen from around Europe. This plugged the city right into this new style.

The "Beautiful Madonna" is another popular type that's common in Eastern Europe. These figures apply International Gothic beauty and aristocratic finery to statues of Mary and Jesus. This is a good example, with it's queenly robes and crown.

Master of Beautiful Madonnas, Madonna and Child (Beautiful Madonna), circa 1390, polychromy on gaize, National Museum in Warsaw

Greater realism from the earlier Middle Ages, but greater elegance and beauty as well. It's similar in painting, where the Master of the Trebon Altarpiece gives us a familiar panel painting treatment of the Madonna and Child.

Master of the Trebon Altarpiece, Madonna of Roudnice, after 1380, canvas on limewood, National Gallery in Prague

Compare the faces, expressions, and attire of this and the Beautiful Madonna up above. Here the addition of the bright blue adds cost and luxury. How different is this from Stefan Lochnar?

Picking up speed as we near the end of the tour, and our last stop - Italy. In the last art post, we saw how Italy was very different from rest of Europe and had a distinct art and culture. But we also saw how Italian artists were part of the creation of the International Gothic - Simone Martini may have been the most important single influence. Italian art continues to be distinct but there is an International Gothic phase there too. In between the early innovators like Giotto and the actual Renaissance.

Lorenzo Monaco, Annunciation Triptych, 1410-1415, tempera on panel, Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence

Three pieces of a altarpiece with the warm colors and fluid curves of the International Gothic. Mary's blue robe connects back to the history of that expensive color and the gold gilding gives it a luxurious look.

Gentile da Fabriano is another International Gothic Italian painter. This painting is a masterpiece of decorative elegance. The delicate pattern work actually seems to flatten the picture out. These paintings were products of the rich Italian courts and not feudal aristocrats. But the style was associated with the high class of it's court origins and appealed to the banking, military, and Church elites of Italy.

Gentile da Fabriano, The Coronation of the Virgin, about 1420, tempera and gold leaf on panel, Getty Center, Los Angeles

The robes are really something. Including the angels.

This was a long post so we'll stop here. This should be enough to give a picture of the International Gothic and end the Art at the Crossroads post. We've spent a lot of time on the Gothic, but it's been worthwhile - it's given the Band a sense of clarity for the next little while. What we see is something different from the Progress! timeline - not just art but cultural history in general. And that there real pivot wasn't the Renaissance but what's called the late Middle Ages.

This is where we find the emergence of separate national and aristocratic international cultures, urbanization - another new culture - and international finance. These new cultures - urban and international - are the seeds of the satanic gray goo globalism that we face today. And this is when art becomes a thing - so we can see a culture teetering on the edge between Logos and materialism. Although fallen humanity toppled the wrong way, it shows us that it is possible to harness luxury through techne to episteme. It also means that art always carries the potential to go sideways. Consideration for a world to come.

|

| Hannah Greer, Heaven or Hell, 2012. |

We'll leave off with the ultimate contrast of the Gothic horror and beauty that we started this post with. Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece is late - 1512 is the year Michelangelo finished the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome. It's a huge multi-part altarpiece that intended for a hospital and not an aristocratic chapel, so emotion-driven piety is it's main goal. And it does so with all the rhetorical approaches we've seen - just at an extreme pitch.

Mathias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, 1512, oil on panel, original sculpture by Nikolaus Haguenauer, 1505, Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France

Great picture of the whole thing. It's been disassembled for display so all three stages can be seen. The original core of the altarpiece was one of those carved wooden scenes by Nikolaus Haguenauer - you can see it furthest back. Grünewald added painted covers with highly rhetorical scenes from the life of Jesus.

This is the original sculpted altar with painted, gilded, regal saints. Anthony, the patron saint is in the center. The intricate carving at the top resembles Riemenschneider. Grünewald painted the wings with scenes from the life of St. Anthony.

The front section is a grisly Crucifixion scene - one of the most wrenching in history. The saints on the wings - Anthony and Sebastian - are connected to healing.

The horror of the Crucifixion is balanced by the International Gothic beauty and glory of the Incarnation and Resurrection. The extremes back to back.

Take a closer look: the horror and anguish of the Crucifixion. The body is impossibly wracked and ravaged in an image of unimaginable suffering. The Marys howl in anguish, while a stern John indicates the price God paid to redeem a fallen world.

And against the horror, the beauty...

International Gothic settings, beautiful colors, graceful angels, and maternal warmth. Birth and death. Joy and pain. The humanity of God as something we can relate to in our human terms.

But Grünewald didn't stop there. The danger in focusing too hard on the humanity of the Son is to miss the divinity. The beginning of life is always miraculous, but angels sing and light pours in from heaven because this birth is God. Death comes to all of us and is often painful or tragic, but this death redeems because it is God who experiences it. Only divinity can meet the price - otherwise we'd hace self-redeemed long ago.