Finishing the Hudson River School & Truth in Apprehensible Reality theme. Tons of art & lessons for the House of Lies

.

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction to the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and other topics have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check and it will be up there.

William Stanley Haseltine, Iron Bound, Coast Of Maine, 1864, oil on canvas, detail

Time to finish the Hudson River School, beast art narrative [BAN], coalescing House of Lies & truth in Apprehensible semi-series. Series, because one flows into the other - usually because of underestimating how long and cumbersome art posting gets. Semi because we didn't set out to do a multi-parter, so it's less coherent than other linked groups. Part 1 [click for a link] laid out the conceptual stuff, then deep dove into the preeminent late Hudson River School Master - Thomas Moran. This post will pick up there with a selection of artists from the back half of the movement.

William Louis Sonntag Sr. 1822-1900

This largely self-taught artist was a central figure in the Hudson River School and had an extremely successful career. His early work shows the usual captivating detail fading into sublimity. But there's a gauzy, dreamlike quality to his distant light and atmosphere that feels epic. Like a mix of luminism and Romantic landscape.

William Louis Sonntag, Landscape, 1854, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum

Moving into his prime, he harnesses this effect to more evocative and challenging times of day. This is a small painting, sketch-sized at only 8 5/8 x 16 5/8 inches. But the finish and sense of grandeur make it feel much bigger.

Think back on the critical nonsense in the Met catalog about detail and feeling. Real creativity rooted in logis and techne sees possibilities in artistic develpments. Tools to be adapted and used. Demons see limits

William Louis Sonntag Sr., Autumn Morning on the Potomac, 1860s, oil on canvas, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Sonntag settled permanently in New York from 1856. His professional connections included a close friendship with famous black American painter, Robert Scott Duncanson. Duncanson was more Hudson River School adjacent than an active member, but they shared core values. He and Sonntag traveled together on sketching trips. It's not hard to see...

Robert Scott Duncanson, Flat Boat Men, 1865, oil on canvas, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

It's crazy how much talent was floating around. Duncanson would be as forgotten by the narrative as the rest had he not been resurrected by racial scholars. But even there, "African-American pioneer" reduces him to a historical curiosity. His - and his contemporaries' - real presence in the history of American art is left out.

Sonntag's other specialty was Italiante scenes. Like other Hudson River School painters, he traveled extensively to apply his skills to new settings. This one's pretty big at almost 5 ft. across.

William Louis Sonntag Sr., Sunset, Italy, oil on canvas

And since Sonntag gave us an unexpected chance to look at Duncanson, here's one of his Italian travel based paintings. Note that we aren't questioning the importance of his background to his career or vision. That would be retarded. Identity is formative for anybody, especially someone as expressive and perceptually sensitive as an elite artist. The point is that people have many dimensions. And in an organic creative culture, talented visionaries from very different backgrounds can find common cause around commitment to the art. That Duncanson’s commitment overpowered oppositional social forces is a statement about him as an artist.

And an artist from a different background who operates within logos and techne actually does enrich the art with new angles and possibilities. Duncanson was pretty much sublime landscapes. But the larger point stands. The necessity is a reality-facing art culture.

Robert S. Duncanson, A Dream of Italy, before 1872, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museum of Art

And one more undated Sonntag that really gets the haunting quality of his best work.

William Louis Sonntag, Lakeside Landscape, 19th century

Before moving on, Sonntag lets us revisit the artistic creation of reality theme introduced with Moran. Nearer the end of his career, Sonntag turned to a main late Hudson River School subject – the grandeur of Yellowstone. The interesting thing is that according to the link, he never actually visited.

William Louis Sonntag, Sr., Grand Canyon, Yellowstone River, Wyoming, 1886, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museum of Art

There is something dreamlike or fantastical about the feel. Part of that is the alien landscape. Part is how it came about.

Sonntag composed his painting after an 1885 photograph by Frank Jay Haynes (1853-1921), the park’s official photographer. The perspective and view show artistic license.

Frank Jay Haynes, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and Falls, 1885, albumen silver print from glass negative, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Haynes photograph was black and white, and the source suggests the coloration may have come from Moran’s 1871 watercolor sketch...

Sonntag's version is lighter and less saturated in color, as watrcolors tend to be.

Moran’s piece was the basis of a chromolithograph for a book published in 1876. Not sure what Sonntag saw.

Thomas Moran, The Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, 1874 -1875, chromolithograph by Louis Prang, 1875,, published in Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden, The Yellowstone National Park, and the Mountain Regions of Portions of Idaho, Nevada, Colorado and Utah, 1876, The Newberry Library

It’s important to remember that at this time, the American West was still the new frontier. Kennedy notwithstanding. Prior to photographs, most Americans only knew of this through some early paintings and what seemed like explorers’ tall tales. Tbe camera proved huge trees, alien landscapes, geysers etc. were all real. As the last post showed, grand colored paintings framed how these were conceived.

There is a monumentality to the black and whites that isn’t entirely realistic. But “photograph” quickly picked up a truth value that it never lost. The features really had to be in front of the camera. But the lesson for us today remains that even the truth of the camera is shaped by how it’s presented and the cultural assumptions it taps into or reinforces.

Timothy O’Sullivan, Shoshone Falls Idaho, around 1868, albumen print

The bit of cultural history that always gets left out is that art influences photography as well. The whole idea of “framing a shot” is an attempt to select a slice of reality that has aesthetic qualities. And aesthetic assumptions are very art-dependent. Watkins was another iconic early Western photographer. It’s impossible to look at this without thinking of how Bierstadt trained people to visualize Western majesty.

Carleton Watkins, Distant View of the Domes-Yosemite Valley, California, around 1866, albumen print

After looking at a couple of these photos, it’s worth looking back to one of the catalog Gammas. Compare the lunatic assertions with the reality of the visual arts. We can all do it. Consider what that says about the intelligence, moral fiber, and perspicacity of what the beast takes as insightful. Even better, compare it to what Moran, the actual painter at the center of the movement, actually said.

I place no value upon literal transcripts from nature. My general scope is not realistic; all my tendencies are toward idealization. Of course, all art must come through nature or naturalism, but I believe that a place, as a place, had no value in itself for the artist only so far as it furnishes the material from which to construct a picture.

The Band has been criticized for being meandering or sprawling. This sort of facile misrepresentation is why we spend so much time laying out relevant elements and basic knowledge foundations. De-contextualized lies that pretend to speak for the context are so common in the House of Lies. We’re bombarded by them on historically unprecedented levels. Being clear about what is Materially real, what is logically coherent and truthful, and how they work together keeps us in Apprehensible Reality. Being-in –the-world as we can know it to be.

Charles Wilson Knapp (1823-1900)

Knapp wasn't a leading figure, but successful enough to give a look at the depth of the movement. There's a clear influence from Sonntag and Cropsey, but his mature work is more prosaic.

Charles Wilson Knapp, Mountain River Scene (Autumn of the Hudson), 1870, oil on canvas, private collection

This is more typical of Knapp. There aren’t a ton of high-res images of his stuff and what we’ve seen has a high degree of consistency. With space at a premium, this will do.

Charles Wilson Knapp, View on the Pemigewasset River, New Hampshire, 1873, oil on canvas, Vose Galleries, Boston

A question to keep in mind as we go through this. Artists of this caliber were rank and file. Picture the profiles that would destroy this level of refined skill over lies about the nature of art and subject matter…

William Mason Brown (1828–1898)

This prominent figure in the second generation of the Hudson River School was known for bright sublime landscapes - especially Autumn scenes - and very detailed still-life.

William Mason Brown, Autumn Landscape, oil on canvas, private collection.

A small [14 x 12] undated scene shows his subtle light and love of Autumn colors.

Brown’s still-life painting is sharper - as expected, from a genre based on capturing the appearance of things. But the light is unmistakably his.

William Mason Brown, Raspberries in a Wooded Landscape, between 1865 and 1878, oil on canvas, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

It wasn’t just Autumn scenes – Brown’s landscapes are always boldly lit. He seems to descend more from the Durand wing of the early movement.

William Mason Brown, Summer Landscape, oil on canvas, private collection

A lot of Hudson River painting is in private collections. This is good for photos – auction houses are tremendous photo documenters of art. But it doesn’t come with the in-depth research that big museums can do. It’s why so many lack even a tentative date or history. We'll leave Brown with a stunning dated Autumnal vision...

William Mason Brown, Autumn Landscape, 1861, oil on canvas

Samuel Colman (1832–1920)

This long-lived artist shows a lot of the qualities that gave the Hudson River School its appeal. Sublime nature, harmony of life and natural beauty, stunning times of day and atmospheric conditions, and travel to other beautiful places. The usual problems with dating and history apply.

Samuel Colman, Evening Landscape, 1864, oil on canvas

An example of Coleman’s travel – the Hudson River School goes to Spain. Here he extends sublime monumentality to the great Andalusian palace-fortress complex.

Samuel Colman, The Hill of the Alhambra, Granada, 1865, oil on canvas It's pretty big at 47 1/2 x 72 1/2 in.

His masterpiece came shortly after. At nearly 5 ft. across, it’s a tour de force of light, atmosphere, and harmonious organic life. We pick up on the creeping threat of uncontrolled oligarchic industrialization. But that’s irrelevant to the historic beauty.

Samuel Colman, Storm King on the Hudson, 1866, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum

That shimmer is a bit different from Sonntag – less graduated by distance. The foreground is more substantial, but not quite as meticulously detailed as with some others. Storm King on the Hudson is a high point, but other applications aren’t so bad.

Colman is varied compared to some of the School. Here’s a more prosaic landscape reminiscent of the Spanish one over twenty years earlier. The brightness comes from the watercolor medium. Watery paints don’t block the paper the same way oil paint covers the canvas. That bright white can shine through in a controlled way. Watercolor wasn’t as prestigious as oil, but it was quick, appealing, and something most of these guys were good at.

Samuel Colman, Rocky Landscape, around 1888, pastel, watercolor and ink on paper

One more for variety’s sake. We haven’t seen a lot of marine art – the preferred subjects tended to be inland. Bricher is a notable exception and there are others. This is technically a river scene, but its appearance is consistent with ocean painting. Light, water, and atmosphere.

Samuel Colman, Shipping on the Hudson, oil on canvas

Edmund Darch Lewis (1835-1910)

The presence of Cole and the early Hudson River School is visible in this prolific artist. The link points out Church and Bierstadt as direct influences. We'd throw Cropsey into the mix as well. We’ll expand the selection a little to do some justice to his different subjects. Look closely and it’s easy to see that it’s the same artist, despite the variety.

Autumn colors and the sublime Eastern wilderness are touchstone. Where the movement was born, wherever its maturity took it.

Edmund Darch Lewis, Autumn Afternoon in the Catskills, 1865, oil on canvas

There’s a quick feeling to Lewis, despite the detail in his paintings. It makes his art feel less timeless. Still ideal and not of the present, but primordial and in time.

The sense of loss that comes with Romantic contemplation of past glory is enhanced by the season.

Lewis is channeling Cole’s rugged forms here, but with stagier light. The self-teaching process is visible in the imperfect blending of impressive effects. Auto-didacticism being opposite auto-idolatry.

Edmund Darch Lewis, A Lake in the Clouds, Mt. Mansfield, 1868, oil on canvas

Lewis is worth a look because his development within his intrinsic limits is so clear. This was painted two years later and has similar features to the previous one. But you can see him figuring out how to make the parts fit together better.

Edmund Darch Lewis, Mountain Lake with Mill, 1870, oil on canvas

This process continues – same basic ingredients, but more coherent and harmonious. The underlying sublime vision of nature – the logos – is consistent. It’s the material techne that is improving. There’s a reason why paintings are called compositions. Just like written and musical compositions, the overall success is based on how well the parts come together.

Edmund Darch Lewis, River Landscape, 1874, oil on canvas

Mature Lewis is a classic Hudson River School painter. Visually appealing glimpses of an ideal world, but without that otherworldly sublimity of Church or Bierstadt. Not quite as picturesque as Durand, but cut from that cloth.

Edmund Darch Lewis, Scene in the Catskills, 1880, oil on canvas

Great artists seem able to swing for the fences, while the very good are more consciously restrained. This is a beautiful scene. But the foreground isn’t as real or the background as awesomely sublime as the best of the movement. Not a criticism. The reality of organic art being meritocratic.

His range extended to seascapes. Here too, he is competent, but without the transcendent air that makes Bricher so appealing.

Edmund Darch Lewis, Seascape, 1881, oil on canvas,

Like many of his contemporaries, Lewis keeps painting successfully long past the point the BAN says art had to be something else. Breaking critical influence and encouraging people to like what they like is the path to organic culture. Why are gatekeepers even needed? Why can’t affluent people just go to a gallery or auction and bid for the most beautiful things? The answer is insecurity. The House of Lies encourages people to doubt their preferences out of fear of seeming like rubes. But they’re objectively repulsive liars who hate beauty. Even if a guide was necessary – and one really isn’t – why on earth would anyone choose them?

Status vs. posturing.

Edmund Darch Lewis, House by the Waterfall, 1900, oil on canvas, private collection

There’s always that slightly folk artish aspect to Lewis that comes back out more in his old age. It’s pleasant work though – easy to see why he had little trouble finding customers. A healthy culture has a variety of artistic options to cater to real differences in taste.

Edmund Darch Lewis, Cuban Landscape at Sunset, circa 1864, oil on panel

We’ll leave Lewis with another Hudson River School mainstay – travel. This little [12 x 8 in.] sketch captures the brightness of the tropical sun.

Julie Hart Beers Kempson (1835-1913)

This female member of the Hudson River School was also part of the only sibling act in the movement. Her older brothers, James McDougal Hart and William Hart preceded her, and all three showed and sold out of the same 10th Street studio building. It clearly ran in the family – her nieces Letitia Bonnet Hart and Mary Theresa Hart were both successful painters. Her name is sometimes confusing on labels. She established herself while married to her first husband, and could support her family after his untimely death. When she remarried, she took her new husband Kempson’s name legally and socially but changing a well-known name was detrimental to an artist’s career.

Here's a gentle early scene.

Julie Hart Beers, Cows in Landscape, dated 1861, oil on canvas, private collection

We weren’t the first to notice the omission of females in the Met catalog. The link recognizes “the full rehabilitation of the Hudson River School” but “failed to include the work of even a single woman artist … of whom there were many”. Hart Beers was one of the best.

Her bigger mature paintings unfold sweeping, balanced compositions with sharp detail. Here's a good example with one of her tells - less resolution in the sublime depths.

Julie Hart Beers, Hudson River at Croton Point, 1869, oil on canvas, Home on the Hudson

Hart Beers’ omission is all the stranger when we realized she was one of the first women in America to have a successful career as a professional artist. Given the nature of the BAN, we’d think this would be significant. Anyhow, her output was on the varied side – she was resourceful at finding clients.

Julie Hart Beers, Ducks in the Woods, 1875, oil on canvas, private collection

This is a good example. Sharp detail up front, fading into that extra-blurry depth. Hart Beers took extensive sketching trips, even organizing groups as part of her art teaching activities. The death of her first husband seems to have forced her to prioritize career advancement in a way most female painters at the time didn’t. Maintaining her daughters’ standard of living being the real outcome.

Julie Hart Beers, Looking upon the River, 1880, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago

There’s variety in the type. Here the woods open onto a sunny pleasant lake. Hart Beers career explains her name issues. She was very much a high status family woman of her era. But her art career was unusual and lucrative. An artist’s name is their brand is the basis of their market value. You couldn’t cultivate the relationships with collectors and clients then change your name on them and expect to remain successful.

Julie Hart Beers, Quiet Brook, Elizabeth, New Jersey, , oil on canvas, private collection

The misty backgrounds have a plein air feeling. Possibly another reason to leave her out of the catalog. Complicates the narrative.

Hart Beers’ second husband was well off, but appreciated her contributions. They built a studio in his New Jersey home, where she could work and be with her daughters. She used the 10th Street studio for showing and sales because it was ground zero of New York art at the time. Her brothers painted there as well.

This roundel is an unusual Hudson River School format, and shows that hustle for high status work. Villard was a bigtime financier and Northern Pacific Railroad president with an estate overlooking the Hudson. Remember, it's the 1880s and the Gilded Age is heating up.

Round painting needs to be designed differently because the shape influences perception. She subtly lines the hill on the right with the curve and frames a sweeping view into depth.

Julie Hart Beers, The Hudson as seen from Henry Villard's House, Tarrytown, Christmas, 1881, oil on composition board, 12 in.

We found another round painting of hers of the same size from the same year. Lack of BAN interest means we can’t tell if this was also for Villard. It’s easy to imagine them as a set, but we can’t say.

Julie Hart Beers, Woodland Scene, 1881, oil on composition board, 12 inches diameter, Collection of Jack and Mary Ann Hollihan

The style is pretty different. More typical woodland scene cut to a circle.

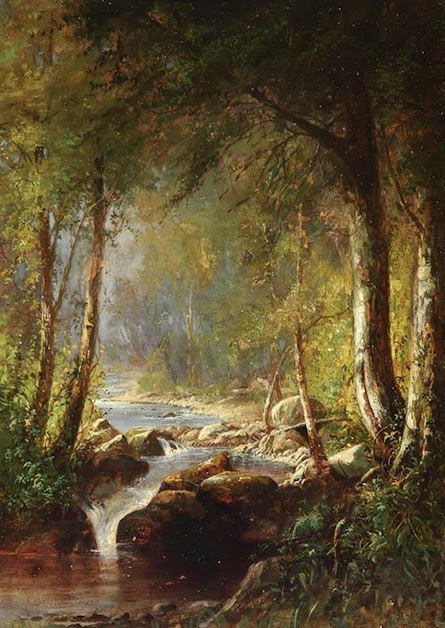

Like many of her contemporaries in the movement, she remains active long past the BAN terminus. It’s irritatingly hard to find good reproductions of her work. Here’s a late woodland stream painted in her 70s. It’s still there.

Julie Hart Beers, Birches by a Woodland Stream, 1908. oil on board, Davis Museum at Wellesley College

There’s a gentle quality to her work that’s pleasant to look at. We don’t care to speculate on gendered attitudes, but will point out that she adds another dimension to the Hudson River School range. Remember that when the BAN Gammas are whining about lacking variety and feeling.

The relationship between the Hudson River and Dusseldorf Schools came up in earlier posts, so it’s interesting to compare Hart Beers to a successful female painter from that movement – the Finnish Fanny Churberg.

Fanny Churberg, Forest Creek, 1877, oil on canvas, Helsinki Art Museum

We have no idea if they ever met. We don’t believe Hart Beers studied in Europe. The similar approaches to the subject are interesting though. More exposure of the false provincials-Eurotrash BAN dichotomy.

We came across this item while digging into Hart Beers’ past – we aren’t joking when we say there’s very little depth on her out there. It’s a word-image hybrid, but with a subject the beast disfavors. The link misidentifies the text - it’s Psalm 23, not the Lord’s Prayer - because of course it does. Christianity amplifies the Hart Beers oblivion effect exponentially.

Julie Hart Beers, Cows in a River Valley, signed lower left, scattered losses, split in panel.

We aren’t sure what to make of it. The battered condition indicates household use over time – probably a wall hanging that that got passed down. The format resembles the old votive tradition – where a picture and some words were made for a church or home in thanks for a prayer being granted. The ones we’ve seen tend to describe the specific event being given thanks for.

Votive painting, 1801, Church of Mariä Himmelfahrt, Berg, Upper Bavaria, Germany

Example of a votive painting in a German Catholic pilgrimage church. In this one, thanks are given for deliverance from a sticky situation with some soldiers without injuries.

Similar layout isn’t proof of anything though. Word and picture pairs are hardly uncommon. It may just be something like a modern serenity prayer cross-stitch or other inspirational ornament. Whatever it is it’s unusual enough to us to deserve mention. And yet another that the Husdon River School vision of the sublimity of nature and organic life was profoundly Christian. BAN Gammas notwithstanding.

Before leaving Hart Beers, we should mention her sibling relationships. All three Harts painted independently and had their unique styles. All three have common Hudson River School qualities as well. Julie has some of James McDougal’s signature tranquility, but with more of a dramatic streak. William is more dramatic than either of his siblings, but he and Julie are probably closest of the three. This is the sort of Romantic sublime that's uniquely William.

William Hart, Sunset on Grand Manan Island, New Brunswick, oil on canvas, private collection

And a comparison showing how close they could be.

William Hart, A Fall Day, 1872, oil on canvas; Julie Hart Beers, Autumn Landscape with River, oil on canvas, private collections

The two paintings are almost identical size - 9 1/2 x 16 1/2 and 11 x 17 inches respectively. William was the most vivid colorist of the family. Otherwise, the common vision is easy to see.

William Stanley Haseltine (1835-1900)

This big name in the later Hudson River School spent much of his time in Europe. What happens is that you realize that "European" in the BAN has nothing to do with the continent or its art. It’s the strawman [cosmopolitan-rube] false binary that is a necessary condition for the narrative’s existence. European simply means a box of inverted theoretical claims from one particular context. Where you paint is irrelevant. The bigger lesson is that beast nonsense is easier to unravel when you know that words mean in beast dialect.

Haseltine was in the Tenth Street Studio Building by 1859. He had become friends with Bierstadt and Whittredge in Europe, making it a logical move. Here's an early work - pre Hudson River School, around age 20.

William Stanley Haseltine, Landscape, around 1855, oil on canvas

He's raw, but the basic vision and balance are there. His development over the next decade as he realizes his potential is impressive. This painting shows the same rough patchy paint, but with sharper detail in the tree and a clear focus to anchor the whole thing. It's small, just 16 x 18 in.

William Stanley Haseltine, A Rest in the Shade, Lenox, Massachusetts, 1860, oil on canvas, private collection

Haseltine comes into maturity with some really accomplished work. His seascapes have some of Bricher's timeless solemnity, but with Bierstadt's brighter energizing colors. This one is really attractive.

Like most of his peers, Haseltine was an accomplished watercolorist. He tended to use them more for small sketch-type works than big finished ones the way William Trost Richards did. The Victorian English really elevated watercolor to a refined art form. It started earlier with Turner, but carried into the 20th century. It’s not surprising Americans would follow. And not just modest paintings like this. Their best will match the best anywhere.

Even a simple work shows impressive techne. Watercolor has a totally flat surface – unlike oil, where surface texture can create different effects. Haseltine gets the roughness of the bark while melting the foliage into the atmosphere.

Watercolor has fluid qualities – it’s in the name. some painters – like Haseltine – bring some of that quality to their oils. He relocated to Europe in 1866 and spent the rest of his life based in Rome. He was active and successful, traveling and painting European landscapes with his sublime style. Here’s a Capri seascape with some similarities to the Nahunt one. That fluid, watery handling of his color is a sign of his maturation.

William Stanley Haseltine, Natural Arch at Capri, 1871, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington

His Italian scenes are lovely. This undated one is reminiscent of Bierstadt’s quieter scenes, but with the unique trees of the Italian countryside.

William Stanley Haseltine, Veduta del monte di Portofino, oil on canvas, private collection

There’s a more dramatic side to Haseltine as well. This sunset is as intensely colored as anything by Church with a peaceful air of contentment. He’s one of the most aesthetically appealing of the group.

William Stanley Haseltine, Sunset Glow, Roman Campagna, around 1875, oil on canvas

Here are a pair of paintings from the same vantage point that shows how different effects could be achieved in the studio. The first is pure early Romanticism – almost like Friedrich. The island seems to radiate a sublime luminescence.

William Stanley Haseltine, The Sea from Capri, 1875, oil on canvas, High Museum of Art, Atlanta

And here’s the exact same viewpoint in a more realistic – if still ideal – style. Clearer than Sonntag. The drawings and sketches gave them viewpoints, perspectives, and light relations. From there, there’s no constraint on the finish but the artist’s imagination.

William Stanley Haseltine, Sunrise at Capri, undated, oil on canvas, National Academy of Design

There’s a picturesque quality to Haseltine that can be hauntingly beautiful. If you look at the mountains, you can still see that rugged Hudson River School look.

William Stanley Haseltine, Lago Maggiore, oil on canvas, private collection

It’s not always gentle beauty, although there’s always a aestheticism to him that’s really appealing. This late work is as dramatically lit as anything by William Hart or Bierstadt. Veiled sun is a great Romantic trick to have high intensity light without the overpowering bright spot. This lets the artist explore more subtle variants in the lighting and color.

Like this…

William Stanley Haseltine, Coast of Sori, 1893, oil on canvas, private collection

Haseltine was productive until the end of his life. His approach was the same as his colleagues in America, just moved to Europe. Travel around, find attractive scenes, and bring out the sublimity. This colors in this one are almost like Shishkin’s more fantastical scenes.

William Stanley Haseltine, Mill Dam in Traunstein, 1894, watercolor and gouache on blue wove paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Of course, there's no one exactly like Shishkin...

Ivan Shishkin, Autumn Forest, 1876, Museum of Fine Arts I. And Mashkov, Volgograd

But Haseltine is a unique talent in his own right, though. His European base, aesthetic touch, and bright fluid colors form another distinct voice in the Hudson River School. An underrated one too – most of them are, but Haseltine seems especially appealing to be so forgotten.

George Herbert McCord (1848-1909)

George Herbert McCord is described as a central figure in the second generation of Hudson River School painters in a gallery bio. It's interesting comparing commercial galleries to After House of Lies pillars. People who aren’t plugged into the unaccountable currents of beast “funding” can’t afford to push narrative too hard. There aren’t that many actual collectors – people rich enough to afford art collecting but aren’t beast-huffing – and competition for them is fierce. This is an actual [boiler room/used car lot-style, full commission, sing for your supper, coffee’s for closers] sales environment behind the most gentile facades. Different emotional content but similar form to the way an undertaker is a picture of solemn compassion and dignity while constantly upselling ridiculously overpriced services. The whole game rests on making people feel the prestige value is worth it.

Not that we’re saying the organic art market is ridiculously overpriced. Art is extremely high culture and the biggest names have always commanded huge sums for their work. It’s much less slimy that the standard mortician schtick. It really is a prestige cultural space where many of the highest status types frequent. It’s also insanely competitive.

McCord isn’t so well-known today. It’s a pity because he’s a very expressive painter with a flair for dramatic light. All the Hudson River School painters did stuff with light, but he’s more likely to swing for the Romantic fences than average.

Apparently, he didn’t receive the BAN DM that after Cole, Christian thematics vanish from the movement.

Commercial galleries serve collectors, but also try to expand their tastes. Get them to buy more. Part of it is showing paintings in the most attractive way. Showing elaborate historic frames - expensive objects themselves - is one way.

The opposite kind of advisor than a Gamma beast critic trying to read history out of art. They never tear down the value of a name they can sell. Quite the opposite – everyone is historically significant, currently underrated, about to be rediscovered, etc. What Judge Judy calls puffery. They can’t go too far because of the nature of the clientele. But you do get a factually accurate positive bio that probably lines up with why they were popular in their time.

Close-ups are another way to show artists in their best light. McCord is a good dramatic light painter, so the same site adds a close-up showing his touch. This way the actual quality of the overall shot can be assessed before deciding to continue.

It’s great for us because we can see him build his effect with graduated layers of clear colors.

McCord was part of the visualizing the unfolding West process like many others. In 1910 he took part in a publicity train trip put on by the Santa Fe Railroad and the American Lithographic Company. According to the link, this included leading the artist to the canyon blindfolded to maximize astonishment, then have them paint in studios built along the rim. These were then exhibited around the country to drum up business for the sponsors – a railway and an art printer-publisher. He also took a publicity trip to paint scenes along the Erie Canal and worked on commission from Andrew Carnegie. We couldn’t find these scenes, but the history is an interesting tie between artistic vision and corporate interest.

Does this impact the pristine appearance of much Hudson River School art? There’s got to be a ton of social, economic, art, and political history all tied together in there. Something a serious academy would look into instead of bleating about smudges. McCord’s paintings of attractive churches with sublime settings and organic community could be used as another example of the understood tie between natural and supernatural sublimity. There’s not even any inadvertent secular transcendence here. The representations are ontologically coherent.

George Herbert McCord, Sunset Over a Town, 1872, oil on canvas, 9 by 13 ⅛ in.

The “corporate” pillar of the House of Lies is a significant problem. The structure is inherently dishonest – representing [buy our crap] with anything other than a direct statement. “Marketing” is intrinsically inverted from productive communication – misdirection and subliminal influence where only one party is informed of the real conversation. Even if the product is good. And like any form of rhetoric, it is easily harnessed to false claims. It’s staggering to contemplate the amount of environmental degradation done in the name of raw avarice. We aren’t retarded – resources are needed for stable society. But prudent stewardship takes care of that. We me the real destructive stuff – the false binary where Mordor-tier centralized atavism = protecting livelihoods while cash flows to unaccountable globalist entities – is nation-tier parasitism.

This one is more picturesque, but the alignment between moral society, beauty, and Creation is even clearer.

George Herbert McCord, Sunday Morning, Riverdale Church, 1877, oil on canvas, private collection

It’s the quiet assertion of basic social realities that is so comforting in an era of destabilization.

He’s capable of the shimmering, luministic style we saw in Gifford, Sonntag, Colman, Knapp, and others. Contrast this placid scene with Cole’s earliest work and the history of settlement gets clearer. That part of the country is still beautiful today. But it must have been something to see when unspoiled…

George Herbert McCord, Watching the Regatta Near Newburgh, New York, oil on board, private collection

Those rich colors are effective in the hands of many Hudson River School painters. The vivid hues and contrasts are what made autumn subjects so appealing.

And it carries over into evening scenes. The reality is that you don’t have to paint en plein air to explore atmospheric effects. The point of outdoor study is to record plein air information so it can be accurately represented in finished works. Why ideologically limit creative time for no real reason at all?

McCord wasn’t limited to deep meditative scenes – he had a more dramatic side as well. One late coastal scene is sufficient to show this.

We’d like to end with a look at the later part of the main two Hudson River School painter’s careers. Church and Bierstadt featured prominently in an earlier post, so there’s no need for introduction. It’s a common BAN tactic to only show a selective sample of an artist’s work, then pretend it’s essentially their sole contribution. These posts have done the opposite.

Frederic Edwin Church

Church enjoyed wealth and public prestige his entire life, BAN fakery notwithstanding. He had a beautiful home and studio in Olana, NY, where he lived with his wife as if in one of his paintings. The skycam at the link is great.He designed the villa for sweeping views of the Hudson River Valley, and the Catskills and Taconic mountains. It's worth a look.

Sometimes people ask how well historic artists did. It really varies depending on success in their lifetime. Van Gogh is a cruel case where he was commercially unsuccessful in life and in now one of the most popular, highest grossing artists in the world. Great for the heirs, but...

As for Church's success in his lifetime, he lived here.

The architecture is a mix of eclectic inspirations that Church encountered on his various travels. There's a Middle Eastern flavor - the name is Persian. The one consistency are the views. The whole site was planned for the commanding vistas that the Hudson River School was famous for.

There’s lots of variety in the features, but note the predominance of lookouts, balconies and porches.

What's consistent is the emphasis on Hudson River School views.

The interior is as lovely as you'd expect from the outside.

Church was on the far end of the success curve, but he wasn’t the only one out there. An organic society that prioritizes beauty has no qualms richly rewarding those capable of delivering it. The inverse of taking the ticket – reaping rewards for manifest logos.

We expect the Churches’ travelling artist pals preferred staying with them than having them to their places…

He painted there as well.

Frederic Edwin Church, Winter Twilight from Olana, about 1871-2, oil on paper; Clouds over Olana, 1872, oil on paper, Olana State Historic Site, Hudson, New York

Information about light and atmosphere in these small sketches could be adapted to bigger works.

And a more finished one – a rare winter scene from Church.

Frederic Edwin Church, View from Olana in the Snow, 1870–75, oil and masonite on board, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine.

An later example of that Autumn theme shows Church's unique light.

Consider all the paintings we’ve seen. It has to be concluded that the Hudson River School was one of the movements that was really good with light. But none of them had a light quite like Church’s. There’s the luminist glare that we see in Gifford, Kensett, Sonntag, and others. The colors of Brown or Bierstadt. The intensity of Lewis or William Hart. And something we can’t quite find the words for. It’s unifying, like a real part of the picture. His gradients are so – not “real” as in realistic – palpable. The light makes his idealistic world feel real. Transfiguring. He’s a legitimately one of the all time greats.

Frederic Edwin Church, Autumn, 1875, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

In his later phase, Church does become more stylistically consistent. There is an element of figuring out a formula that works after years of fiddling in the studio. There’s also the reality that people paid top dollar for these and expected certain things. Olana didn’t come from irritating clients.

We didn’t look much at Church’s travel paintings. These examples show that consistent bright central light. But closer look shows each had slightly different properties. Some of this would be based on his observations of the different conditions. And some is a master light painter experimenting with his art. The first is partially veiled light by cloudy mists. Diffuse orange and indirect yellow in the sky and a bright spot on the ground.

Frederic Edwin Church, Vale of St Thomas, Jamaica, 1867. oil on canvas, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Much like Claude – an earlier master of light – Church favors morning and evening, when the sun’s low. He’s stylistically different and not looking for the same effects. Claude used it to tug the heartstrings over a lost golden age, Church contrasted the bright orb and low light for sublime effect.

Frederic Edwin Church, Tropical Scenery, 1873, oil on canvas, Brooklyn Museum

In this Syrian scene, the blazing evening light has a ruddy desert tinge. The haunting loss of Claude’s ancient sunsets is replaced with solar power. Where the remains of antiquity and natural formations alike witness its glory.

Frederic Edwin Church, Syria by the Sea, 1873, oil on canvas, Detroit Institute of Arts

And speaking of the Middle East, we’ll leave Church with a few different travel paintings. Critics tell us light experimentation is proto-avant-garde when it’s Impressionist and repetitive with Church. See why we have such disdain for these puppeteering frauds? One advantage to hierarchical thinking being reflexive is realizing when the structure is deficient, infinite yeahbuts are irrelevant.

His extensive travel and commercial success would be symbiotic – the travel was an endless source of subjects for customers, and the success funded the travel. These posts show travelling was pretty normal for Hudson River School painters – BAN blather about “cosmopolitanism” notwithstanding. But Church was an extreme for the places he’d go. The first hangs today at Olana.

Frederic Edwin Church, El Khasne Petra, 1874, oil on canvas, Olana State Historic Site

Interesting painting of the stone city of Petra. The narrow pass entry is one of the world’s most striking approaches. He painted it quite faithfully - no sublime light effects needed here..

Piñataing the BAN is so ridiculously easy when looking at paintings that it has to be intermittent. Otherwise it will become repetitive. The critics team-wrote a fiction piece, pretended it applied to real artists, and the House of Lies [Art] wing followed. That’s it. The blunt simplicity makes it more horrifying, but it is simple. And the ubiquity of the fakery means it fails in the same simple ways every time. Periodic reminders are useful and amusing, but only periodically.

His work is so beautiful. Looking back over his career shows tactics and solutions he could return to when needed. Here’s an ideal view of Constantinople, framed like an Adirondack boat scene but opening into sublime cityscape.

Note how everyone is relaxed from the painter's viewpoint. When your government isn't associated with fomenting war and instability, being there doesn't bother people.

Frederic Edwin Church, Al Ayn (The Fountain), 1882, oil on canvas, Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

And finally, a late return to Arctic subjects - the fruits of the sort of trip only the wealthy could do - especially in relative safety.

Frederic Edwin Church, The Iceberg, 1891, oil on canvas, Carnegie Museum of Art

A fitting farewell, but we can’t see off Church without Bierstadt.

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902)

Church’s great contemporary also stayed active through the later phases of the movement. There’s a mix of classic Hudson River scenes and Western grandeur. [Art] had no place for him anymore – luckily beauty and Creation are independent of the mewling of liars.

This sunset study foreshadows Moran. Checking the date, direct influence is likely.

Albert Bierstadt, Salem, Massachusetts, 1861, oil on panel

Here’s a nice take on a familiar theme. Bierstadt’s delicate sunset paintings are much less known that his Western grandeur. Different kind of natural sublimity that shows his underrated range. Not the absence of any of this from the BAN.

Albert Bierstadt, Autumn on the Lake, 1860s-70, oil on board

It’s not just sunsets, although they are a unique source of beautiful light and color. That delicate handling works any time of day. We’d look into the BAN to see what the experts say, but…

Albert Bierstadt, View on the Hudson, 1870, oil on board

Jumping into the 1880s, the sunset subtlety is still there, but now the majesty of the Western experience has been assimilated. Mature Bierstadt, carrying the natural sublime to the edge of fantasy. He's an underrated nocturne painter, along with his other skills.

Albert Bierstadt, Lake in Moonlight, circa 1882, oil on board

Niagara Falls is another Hudson River School landmark. This version leaves the background indeterminate and focuses on the double rainbow. God’s covenant shining forth from the beauty of his Creation. Consider the difference between a culture that sees it’s environment as a valuable part of a fulfilling life and the House of Lies.

Albert Bierstadt, Home of the Rainbow, Horseshoe Falls, Niagara

We can’t leave Bierstadt without a look at that Western grandeur. His travels took him to the West Coast as well as Yosemite. Accumulated study sketches make it difficult to tell how scenes were composed. Here are two famous mountains, painted about a quarter century apart.

The sunset light is suitably evocative. And the native canoe shows how early this is in the history of the American West.

Albert Bierstadt, Mount Hood, Oregon, oil on canvas, 35 x 60 in., circa 1860s

He handles the mountain in a similar way in the later picture, but the goal of the painting is different. It’s actually a more traditional Hudson River School sweep from detailed foreground to sublime distance. All painters have personal styles. But there’s variance within that they can use to get the emotional effects they want.

Albert Bierstadt, Mount Rainier, 1890, oil on canvas, 54 × 83 inches

We’ll finish with some later examples of his most famous mode – fantastical mountain visions. One of Bierstadt’s signature traits using bright clear light on vivid color to create fresh air clarity. Here it is again.

Albert Bierstadt, Mountain Landscape, oil on paper laid down on canvas, private collection

Here he is combining that visionary quality and his autumnal painting in a small painting [14.5 × 20 in.] on the West Coast. If at this point there’s any credibility left in the BAN, we give up.

Albert Bierstadt, Mount Baker, Washington, 1891, oil on canvas

He continues painting right to the end of his life. Bierstadt remained commercially successful despite BAN capering because people like being blown away by awesome art. It’s reflected in his sales record. The really outrageous prices need BAN boosting. The huge launderyish sums come from House of Lies players and need official House of Lies direction. Then there are old masters like Leonardo and Rembrandt who have been esteemed for so long that almost everything is locked down in museums. A big Bierstadt now routinely pulls seven figures. This reflects organic appeal in the collector market. There are still Hudson River paintings turning up for thousands, but not the big names. And we doubt those bargains will last.

Sign off with the majestic mountain style applied to Romantic Europe.

Albert Bierstadt, The Morteratsch Glacier Upper Engadine Valley Pontresina, 1895, oil on canvas, The Brooklyn Museum

That will have to be it for now – the post has sprawled enough to get unwieldy. We’ll do a follow-up with the late Hudson River School adjacent and real influence, but it will be a bit. These posts are hugely time-consuming – the reading, researching, formatting, and linking takes hours that have to be prioritized. Speculative posts take time too, but they’re different. Thinking things through can be done passively in other contexts. Making thought diagrams with simple 2D tools helps us firm up our understanding. It’s fun work in the way checking labels and blasting through old specialty books isn’t.

The length is necessary to really give a feeling for what the Hudson River School was like. The foundational inversion of art is the pretense that Abstract rules apply to Material creativity. Not logos as a guiding principle to manifest in infinite facets. Rules telling artists what and how they have to paint. The reality is opposite. Artists create out of a mix of cultural ingredients and personal genius. It’s why their work is accessible to people, but wondrously original and always changing. Patterns – styles, schools, movements, etc. – emerge in hindsight. Real expertise comes from breadth of knowledge. The more are you’re aware of, the more patterns you can see. The BAN uses selective presentation and narrative overwriting to cast movements and cultures in the roles it needs them to play. Knowing what was going on is the cure.

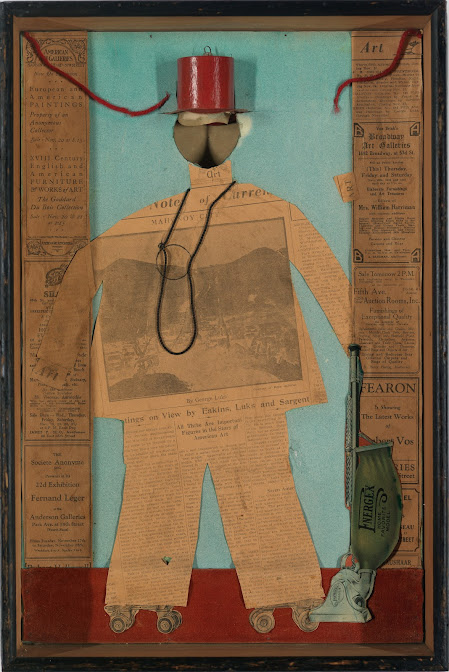

Alexander Z. Kruse, Self-Portrait of an Art Critic, 1936, oil and tempera on canvas, The Wolfsonian–Florida International University, Miami Beach

There’s no need for a summary torpedoing of the catalog narrative. We’ve reiterated the big faceplants throughout, and it’s easy to go back over the lowlights in part 1 if you want a laugh. The larger point is a real practical look at how narrative engineering works over time. The first component is the initial replacement of what really happened with a top-down inversive narrative. Comparing the critics’ “Hudson River School” to the actual art makes the process as obvious as any current House of Lies joint. That alone makes it worth a look. But the second part puts it over.

The catalog frames their selective history with the current role in the BAN. Its claim to “rehabilitate” the Hudson River School seems to be widely accepted – consistent with the Met’s status as world’s leading research museum. From the credentialist side of the House of Lies, it’s that authority that lets it read the banished back into Art!. But it comes back as a chapter in the Progress! to Art! – just one historically interesting enough to consider. It’s also part pressure valve and part unintended consequence of the incoherence of the beast system.

Contradictions

The schizoid thing about institutions like the Met is that they’re also committed to their missions. Not to the point of challenging the House of Lies, but within its terms. It’s why these internal contradictions pop up. Museum professionals come through a ferociously competitive process with tons of applicants, few spots, and huge amounts of private money flying around. Rigorous research and preservation of their collections is a huge part of advancement at the highest levels – even with all the inversion. Professionalism and conditioning often trumps ideology in limited circumstances. Curatorial, research, and technical staff will work through everything in the collection to build internal resources and find exhibit ideas. Boosting value – even of something disdained – boosts credential prestige. And that’s the air these people breathe.

They also take outreach seriously. Narrative promotion, but also perceived leadership in making high culture available to the masses. The Met’s free resources are kind of unreal. Over 400,000 high-res pictures of art in the collection with full identifying information and whatever notes are available. Hundreds of essays, timelines, full downloadable catalogs, technical reports – with no sign-ups or paywalls. The museum’s huge endowments come from Gilded Age philanthropists with charges to serve the public. Whether that was sincere or reputation washing is irrelevant. The money came with the stipulations and the Met has taken that task seriously. We’re immensely grateful for that and all the other institutions that make this stuff available. For all the problems with the collapsing beast system, we’ve never had more access to culture and history.

From the link - As part of The Met's mission to reach the broadest possible audience, Watson Library is making as many of these publications available for free online as possible through our Digital Collections. To date, all known publications from 1869 to 1993 to which The Met owns the full copyright (over 2,300) are currently online, and titles are continually being added.

Watson Library also works closely with the museum's Digital and Editorial departments to share content for this collection and MetPublications, which, in addition to providing PDFs of nearly 600 major publications from 1964 to the present, also provides online preview access to in-print and shared copyright publications.

Institutions like the Met put a lot of effort into understanding and adapting new technologies for outreach. But as more better quality images are in circulation, it gets harder to present the old BAN as a just so story. Educational bloat also means increasing numbers of sincere students and academics looking for projects. They also get sucked in by unexpected beauty. Like the effect of hearing modernists’ sneering dismissal of academic art then seeing academic art. This just means the BAN adapts and treats the former speedbumps as “historical interests”. The result is the weird experience where visiting a museum feels like two totally different things. Historical and cultural art that makes sense and bizarre modern nonsense, all presented as if somehow the same. Although it does make visiting huge institutions more efficient when you can strike off half the building.

Anyhow, that’s the pattern. Think about it through form-content. The form is nonsense. Ignore the framing narratives and the House of Lies evaporates from everyday life. But the content is a massive, growing universe of art and culture. Take that for yourself. See what’s really there. And cast the beast critics, Gammas, and other soulless creatures of the narrative into the outer darkness where they belong.

Arthur Dove, The Critic, 1925, paper, newspaper, fabric, cord, broken glass, watercolor and graphite pencil on board, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

,%201870,%20oil%20on%20canvas,%20private%20collection.jpg)

,%20A%20Rest%20in%20the%20Shade,%20Lenox,%20Massachusetts,%201860,%20oil%20on%20canvas,%2016%20x%2018%20in.jpg)

,%20Veduta%20del%20monte%20di%20Portofino.jpg)