Back to the Arts of the West with a dive into the so-called Northern Renaissance. Spoiler alert - it's not. But the recent posts on representation on art and religion let us better understand what was going on. How it relates to late medieval piety in the prelude to the Reformation.

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction to the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and other topics have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check regularly and it will be up there.

Rogier van der Weyden, central panel of The Last Judgment, between 1446 and 1452, oil on panel, Hospices de Beaune

Posting has been sporadic so it’s a good time to get back to the Arts of the West journey. It’s not just an issue of life getting in the way – there is also the need to consider future directions. Lately we’ve become preoccupied with the centrality of representation – broadly defined – in pretty much everything.

And how that allows representation to become the vector for the broad inversion we see today.

It's a long reflection. Here are the links if interested - they're not needed to follow this post.

The problem with something this fundamental is that it can be hard to see. People notice the meaning of words being twisted for nefarious ends. Values inverted and culture hollowed out. Religions violating core precepts and the pretense that opinion means… anything at all, really, in the face of reality. All these and more only scratch the surface of the wholesale collapse of modern society. Together the scope is dizzying, even demoralizing. But the underlying commonality is singular – the misuse of representation to functionally replace the thing the representation was created to represent.

Not the most elegant phrasing, but generalities have to be general.

John Smith, The world turn'd upside down, 1646

This print was a reaction to a parliamentary decision to ban festive Christmas celebrations. Intolerable to the English of the day - almost quaint in light of the degradation and inversions of the modern beast system. The picture captures the sentiment though.

Consider this. Everything we can think, know, communicate, believe is filtered through and expressed representationally. This isn’t insightful – it’s obvious in our early posts on Pierce and signs. What isn’t obvious are the implications. It’s one thing to summarize some esoterica like the Kantian noumenal and conclude that reality qua reality is not directly accessible without some sort of conceptual filter.

It’s another to really consider what it means to have everything mediated somehow.

Even perceptions are mediated by internal neurological processes.

We perceive external reality, but the perceptions themselves are mental images. That is, mediated representations. This is not some bong-fueled dorm room philosophizing that nothing's real man. It's simple acknowledgment that representation is an inherent part of human being-in-the-world. Something we have to work with.

We could distinguish between “natural” representation – sensory activity taking place before we are conscious of what we are seeing, and manmade representational systems like pictures and languages. But there is no way to “prove” that there is no interdependence between them, or to what extent if there is. What matters is that the reality we inhabit - regardless of it’s qualities – is accessed, accommodated, understood, interacted with, etc. through expressions that aren’t the reality itself. That aren't reality qua reality in philosophical… representation.

This means that all our reactions to reality are an endless dialog of representations.

Words, thoughts, symbols, actions in response to words, thoughts, symbols, actions in an endless dance through time. Now consider this. The representation we respond to doesn’t have to be truthful in order for us to respond to it. A false impression triggers the same patterned response as if it were true.

False alarms and their attendant costs are one example. False flags to impel destructive action are another. But any con or scam falls into this pattern - even honest errors.

Because we access reality through representations, representations that are detached from reality generate the same response as when they're truthful.

Theoretically, natural sense impressions correlate to reality through experiential feedback. The color and radiant heat of a red-orange burner indicates not to touch. The sight and sound of falling rain reminds us to grab an umbrella. But even these can deceive in the right circumstances – optical illusions, for instance.

Or a mirage...

We are interested in are the manmade representations. All the languages, semiotics, structures, behaviors, etc. through which we think, feel, and act. In theory, these begin by expressing basic realities then grow in complexity to more abstract topics. In the last few posts, we were looking at the large representational complexes that make up our concepts of art and religion, and how those were historicaly inverted.

The same process is universal. From the last post...

Expand the diagram

1. Representation makes reality qua reality knowable to human minds

2. Representation gets taken for reality - replacing it in human minds

3. Representation inverts reality & reality is treated as if it were the false representation.

The now-disconnected and inverted representation is still presented as standing for the Truth it disconnected from and inverted. In the case of "the Church", Jesus' message becomes whatever the narrative engineers want it to be.

And as long as people react to the now-false representation as if it were true, it might as well be magic. Consider - magic is bending real outcomes through will. A lie that changes real outcomes is doing just that. There isn't the transformation in the underlying reality, but the end result is comparable. In the false alarm example, whether magically creating a fire that triggers an alarm and makes first responders come or pulling a false alarm, the firefighters act the same. At least until the deception is uncovered. In the religion example, magically compelling people to sin and tricking them that sinning is "really Christian" deprives them of their path to salvation either way.

Any lie or scam that makes you respond as you would if reality were different.

From the deceiver's perspective, all that matters is that the truth isn't uncovered until the desired outcome has already occurred.

Politics is based on this - and not one "side" either. SJWs imagining fake utopias or “conservatives” blathering on about impossible “freedom” both impel reactions to reality that are empirically false. And in both cases, proceeding as if they are real has dyscivilizational outcomes. Literally the evisceration of organic community and socialization. The problem is that actual reality is elastic and can tolerate a certain amount of inversion before collapse becomes inevitable. The gradual diminution of social cohesion and quality of life.

It's not like we weren't warned...

Note how retards like to misrepresent this passage on the consequences of idolatry and turning away from righteousness. No, God doesn't "punish the innocent". What it means is that inversion has consequences. Damage that reverberates across generations. How the societal cancers induced by the greed-driven, hedonsitic, self-righteous materialism of the 50's and 60s have only recently become visibly crippling.

Reality didn't change. But the idiot collective collectively pretended it did. Now, where did rational, moral, prosperous, stable society go?

This kind of "magic" is not actually speaking reality into existence. It’s acting as if false representations were reality during the lag time between acceptance of the lies and their fruits. Of course, if anyone can foresee the toxic outcomes, the moral culpability of the self-pleasuring followers is that much greater.

We can frame the arts of the West posts in representational terms. Because the posts slowly trace how a complex set of representations called art – techniques, theories, social placements, users, expectations, symbolism, etc. – came to...

...1. define our basic formula of Logos+Techne - itself a representation, but a truthful one

Adriaen van Ostade, The Painter in his Studio, 1663, oil on wood, 38 × 35.5 cm, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

The artist uses his mastery of refined techniques to visualize truths.

...2. Took the place of L+T - representation-reality inversion

Felicien Myrbach-Rheinfeld, Candidates for Admission to the Paris Salon, late 19th century, pen and brush on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The institution claims the power to decide what art is. There's still techne but doesn't have to be.

...3. Then projected the opposite of L+T – what we call Art!

James R. Huntsberger, 1913 Armory Show, 2014, print

Enter modernism. The institution ditches any pretense of logos or techne. This degrades a once-noble expression of culture into degenerate trash.

The last couple of posts noted the same process in religion. A complex set of representations called Church or Christianity came to

...1. Define our understanding of Christ’s saving message

Figure holding chalice in an Agape Feast, 4th century, Catacomb of Saints Pietro e Marcellino, Rome

The Agape feast preceded the Mass / Eucharist in the early church.

...2. Took the place of Christ’s saving message

Arnolfo di Cambio, Pope Boniface VIII, around 1298, Opera del Duomo Museum, Florence

Medieval popes attempted to build imperial power, living in palaces and nonsensically claiming to deprive Christian salvation over political disputes. Boniface took it to an extreme, claiming absolute authority over everything. The French king dealt with him like any second-rate monarchical wannabe.

...3. Then inverted into the opposite of Christ’s message.

...

...

...

Anyhow.

At which point it became easy to see how this rough process happened in almost every area of human activity.

Consider our subtitle – dismantling Postmodernism. That whole rancid ball of lies is based on the fiction that reality is “discursively constructed”. Remember Prof. X Foucault and the ersatz “philosophy” of pretending representations are the objective reality that they were historically created to represent?

Consider our motto – what can we know and how can we know it? Representations that don’t correspond to anything real allow us to know nothing. The only "knowledge" they offer are the valueless opinions of ontologically inconsequential randos. That is, nothing.

Anyone who claims that meaning is just representation - discourse, or whatever - but expects you to accept it as meaningful is a confessed liar, likely a psychopath, and should be avoided. That’s simple logic. Expecting something to be taken as true when you deny the possibility of true is psychotic. Or evidence of just how stupid “the average person” is. Upon further reflection, embrace the power of and.

Obviously the primordial nature of representation is something we will be returning to. Consider that the Bible presents Logos in Creation as a foundational speech-act. And it’s just as obvious that the ontological hierarchy itself is a complex representation.

A better take on semiotics is needed – one that doesn’t assume fake beast materialist Flatland instead of metaphysical fullness. This isn’t something we can dash off in a post, but needs to be carefully thought through. Otherwise, the how can we know it part of the motto will be stuck in the dark.

Returning to the Arts of the West, a fuller take on representation is clarifying. Works of art – painting and statues – are obviously representations of various things. But “art” itself an idea or set of cultural practices and/or institutions is also a representation. A more complex one - or what we call a representational complex. The medieval art posts noted how our fine or visual arts didn’t really exist as a distinct concept. There were picture makers, but not “artists” as a distinct, privileged form of creator.

The Renaissance posts considered how genius artists and humanistic ideology combined into a new set of definitions and associations. This is not our insight – even the beast narrative recognizes this as the birthplace of a formal concept of art in the West.

The Sistine Chapel with it's paintings by Michelangelo and other masters is a landmark of Renaissance art. Defined values, venerated names, defined progress, and theoretical presumptions are all parts of this new art.

What is our insight is how this overlaps with a humanistic inversion in the Church at the same time. Our occult posts looked closely at satanic inversions like Hermeticism, alchemy, Freemasonry, Prometheanism, and so forth and how these were slipped into institutional Christian thought. Like feces in the holy water. Our most recent occult post considered how the idolatrous fraud impostor “Pope Francis” is still following this inversive pattern.

With this post we are picking up the thread in Northern Europe, where we saw a different artistic tradition forming than the Italian one. We looked at the International Gothic as a form of the beauty of holiness and the rise of aristocratic power jacking religious truth. We also looked at the more visceral and horrifying side of the Gothic as something striving to meet the changing religious demands of the public. Click for link.

Rogier van der Weyden and workshop, The Exhumation of Saint Hubert, late 1430s, oil with egg tempera on oak, National Gallery, London

The saint being translated was the 8th-century Bishop of Maastricht and Liège, who died in 727 and moved in 825. But note the date of the painting and the 15th century costume of the figures. There was no painting like this in the 9th century.

The intense desire to see the uncorrupted body of the saint is a sign of this newer, viscerally personal religious impulse. We think is also drove the development of "Northern Renaissance" art.

The idea that the public were craving an increasingly tangible, physical, sanguinary tie to God meant representational complexes were changing. Both the visual arts like van der Weyden's painting and popular forms of religion. Put this way, the old representational complex of religion – a complex created to connect finite material humanity to the inexpressible qua itself revealed Truth of ultimate reality – was failing. Failing meaning it was not meeting collective spiritual needs. This meant people were reaching for more and more powerful or satisfying representations to assuage their anxieties and fears.

Consider the Besloten hofje - enclosed garden or hortus conclusus. It's a Reformation-era kind of altarpiece consisting of a wooden box packed with figures and devotional objects and organized like a garden. The hortus conclusus was a medieval convention based on the Song of Songs and a metaphor for virginity. Note the fence with closed gate at the bottom to show the private nature.

Mechelen, Besloten Hofje with Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, Saint Ursula, and Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1513–24(?), painted wood, silk, paper, bone, wax, wire, and other materials in a wood case, Musea & Erfgoed Mechelen

This one is pretty typical, with the central box filled with items that demand attention. Handmade flowers made of fabric, wire, clay, and other things join relics and medallions surrounding sculpture. The density of the stuff is ironic considering the idea of a gated closed garden. Something this eye-catching hardly screams keep out.

Close-up of the central box and its dense collection of items. Note the craft in the handmade flora. The painted saints are typical of smiling courtly International Gothic figures. They complement the idea of the sacred garden by representing the ideal inhabitants. If you are meditating on the piece, it leads to connections between the saints, the beauty of holiness, and the symbolism of the garden.

Other items connect the Besloten hofje to other signs of this visceral, tangible late medieval piety. The bone relic from the legendary 11,000 virgin martyrs of St. Ursula fits with the intense cult of relics of the era. This adds spiritual "reality" to the purely representational statues and real sanctity to the fictive garden.

The wax medallion of the Resurrection is dated 1513 and adds another devotional link. These were tokens of pilgrimage or similar participatory activity - often directed towards relics like the bone.

Taken together, the Besloten hofje is a great overview of that intense religious devotion in the build-up to the Reformation. The cult of the saints and its relics, pilgrimage, emotionally-engaging statues, in a setting designed to get you looking closely. And slowing down and lingering moves you into a mindset conducive to pious reflection. If devotional art is intended to aid prayer, this is like a demonstration.

Here's another one, just because these things are pretty far out.

Besloten Hofje with Calvary, the Virgin, and John the Baptist; panels of the patrons with St. Peter and St. Cornelius, around 1525, Museum Hof van Busleyden Mechelen

One thing the so-called Northern and Italian Renaissances share is a relatively high level of literacy. The difference is that in the 14th and 15th century, northern Europeans really don't show that early humanistic interest in classical texts. Their bestsellers are more medieval tales – some of which are based on ancient ones – and religious literature. This is a generalization, but a sound one for the purposes of this post. The popular texts complement the emphasis on seeing and feeling that we see in the art.

The Modern Devotion or Devotio Moderna of Geert Groote and Florens Radewijns was a late 14th-century attempt to “reform” Christianity. The idea was to focus on the humanity of Christ in an immediate, rhetorical way. As opposed to the abstract divinity of Scholastic theology – the “old” devotion. Simplified rhetoric rather than complex dialectic.

Excerpt from a Middle Dutch book of hours from Brabant, translated by Geert Groote, 1475, University Library, Ghent

Translating prayer books into the vernacular was part of this broad humanizing appeal. It also foreshadows vernacular Bibles in the Reformation.

The Devotio Moderna stressed meditating intensely on the Passion, Eucharist, Four Last Things (Death, Last Judgment, Heaven, and Hell) and other moving subjects. Not hard to see the similarity with the increasingly vivid and emotional art we're looking at. Thomas à Kempis’s incredible popular and influential The Imitation of Christ - completed in manuscript in1427 and first printed in 1472 - built on this approach. It’s impossible not to see the meditative, imaginative patterning after the human Christ in the art of the day.

Note the wings from our Besloten hofje. The patrons are shown reading prayer books and meditating while protected by Saints James the Greater and Margaret of Antioch. They show the devotional connection between prayer and reading and the visual experience of the artworks.

Patrons and their saints meditating in parallel to art wasn't limited to things like the Besloten hofje. They're ubiquitous in Northern painting of all kinds.

This diptych is a good example. A diptych is a pair of related pictures - like the wings, but with no main central image. The two work like a visual conversation. This lets us see the 15th and 16th century desire to the sacred. On the right Margaret is visualizing the Madonna. So when she looks at her picture she is seeing herself imagining the thing she is praying about. Visions of visions is a vain effort to get closer to the divine.

Anonymous, Diptych with Margaret of Austria Worshipping, 1500-10, oil on panel, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent

Other popular medieval texts like the Pseudo-Bonaventura’s Meditations on the Life of Christ, Ludolphus of Saxony’s Life of Christ, or Jacobus de Voragine’s The Golden Legend – a collection of saint’s lives – also encouraged meditation and inward private devotion. Historians call this “affective piety”. With paintings like the diptych above, we can’t prove the artists were illustrating specific texts.

Other times we can.

Master of Jacques de Besançon, illustration from Ludolf of Saxony's Vita Christi (Life of Christ), 1474, University of Glasgow Library

Ludolf's book encouraged meditating on Jesus' life in an intense visual way. Imagining the events so as to participate virtually. This illumination shows Ludopf in prayer with a text but focusing his imagination on the Crucifixion - as if it were taking place in his actual room. Note the other instruments of the Passion as well.

Also note how his books are present, but closed. They are important, but only as a vehicle. once the mind is directed to the right place - the life and sufferings of Jesus - their work is over and they can be put aside. This picture is a perfect illustration of how this imaginative, visceral devotion worked. And how art could visualize it in turn.

These are just a few examples, but they all point to the same thing. In each case, art and devotional literature reflect the same religious culture. One that kept trying to get closer human contact to holy personages. And this endless, unrequited drive to get closer tells us that the old representations failed and the new ones weren’t getting it done either. Chasing the spiritual dragon until Reformation.

This means the representational complexes of Christianity in the late Middle Ages were failing from two directions. The papacy with dreams of empire and Hermetic blasphemies from the top down. And a more grass-roots spiritual emptiness in the flailing, failing formulas that make up the representational complex. These probably aren't unrelated. Broad-based spiritual crisis and an inversive, un-Christian hierarchy are symbiotic.

Pinturicchio and assistants, Hermes Trismegistus with the Zodiac, 1493, fresco, Room of the Sibyls, Borgia Apartments, Vatican Palace

There is a slim chance this magus isn't Hermes, though that what most sources appear to call him. That it's in the "Room of the Sibyls" in the pope's private apartments is just the cherry-shaped turd atop the blasphemous sundae.

Raphael and workshop, detail of the Coronation of Charlemagne, 1514-15, fresco, Vatican Museum

Hedonist and art lover Leo X Medici was pope when Luther posted his 95 Theses - the symbolic kick-off of the Reformation in 1517. Two years earlier, Leo was reliving early medieval power games in a grand fresco of Leo III crowning Charlemagne - a gesture interpreted as showing the pope was a superior authority to the emperor. Leo III is a portrait of Leo X and Charlemagne is Francis I of France.

Apparently the "vicar" of Christ was busy wallowing in material pleasure during the "render unto Caesar" bits.

Woodcut of indulgence selling, title page of On Aplas von Rom kan man wol selig werden (One Can Be Saved Without the Indulgence of Rome), Augsburg, 1521

Indulgence peddling - selling absolution for sins - was one of the more egregious offenses that triggered the reformers. To be fair, indulgences had been connected to acts of piety - cash sale was a later development. And the peddlers often promised things not in the "official" theology. At the same time, "as soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs" was a popular saying.

Leo's plenary indulgence of 1515 - to fund the new St. Peter's project -"covered" almost any sin, including adultery.

Pauquet engraving after P. N. Bergeret, The deathbed of Raphael Sanzio: Pope Leo X scatters flowers on his dead body, 1822, Wellcome Collection, London

Two years after the 95 Theses. Perhaps if Leo had shown the same concern for Christianity that he did his favorite artists and construction projects...

Representational failure from above and below. And since art and religion march together, we can see the consequences in both. Northern European art continues to produce different forms than the contemporary Renaissance Italians. And the Church fragments into the Reformation.

There are problems with “the North” from the Band's overview of the Arts of the West perspective. It’s a much larger and less culturally unified area than Italy. Big kingdoms are forming and the Empire is a constant presence. Then there’s the lead-up to the Reformation (duh) which engulfs much of the region but not all of it. We don't see quite the same kind of religious dissatisfaction in Italy. Spain is involved in reconquering the peninsula until almost 1500. England is a world unto itself. To say nothing of Eastern Europe.

Books and timelines certainly try and define it as a distinctive thing. These are pulled from quick image scans for "Northern Renaissance art" and "Northern Renaissance art book". The prevalence of Van Eyck and van der Weyden in the 15th century and Holbein and Bruegel in the 16th points to a pre and post-Reformation split.

The 15th century version is really geographically and culturally limited. Instead of "Northern" Renaissance, Flemish or Netherlandish makes more sense. Perhaps Burgundian. It's as if a tiny pocket of northern Europe is treated as a proxy for everything north of the Alps.

Could it be... discourse?..

Why yes it is.

Dividing the art of Europe into the Italian and "Northern" Renaissances is more a consequence of beast narrative than historical reality.

What we are really looking at is an outgrowth of the International Gothic that was influential because of the network of noble courts. This centered on the Netherlands - Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, parts northern France ruled by the Valois dukes of Burgundy from 1369-1477. This was a cadet branch of the French royal line that presided over a bizarre but extremely prosperous and artistically influential court. A blend of retardaire faux chivalry in ducal circles and cutting-edge mercantile prosperity in the bustling Netherlandish cities.

Northern Renaissance works better as Burgundian Renaissance. But Burgundy goes poof as the artistic innovations spread to neighboring areas. France and "Germany" or the Empire in particular. Also missing is any notion of cultural "rebirth". That is, Renaissance.

So neither broadly "Northern" - other than in relation to Italy, nor "Renaissance" at all - other than being contemporary to the Italian Renaissance. There are similarities between the Burgundian court and prospering Netherlandish cities and the contemporary city-states of Renaissance Italy. We already mentioned high literacy. Wealth and heavy official support for art and culture account for the innovative arts of both regions.

But there are big differences too. Noble courts all over Europe amused themselves with chivalric LARPing - we've mentioned this in an earlier post. This at a time when warfare had made the old medieval knight obsolete on the battlefield.

Tournament combat from Le pas des armes de Sandricourt, 1493, parchement, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal. MS 3958, f.11v, Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Dukes of Burgundy were especially given to this. It's an odd counterpoint to the modern bustling economies of the Netherlandish cities that they ruled over. The wealth this economic activity generated allowed for the courtly games, but it's still an odd combination of old and new.

The pas des armes or "no weapons" was a 15th-century version of the joust where participants role played - literally LARPed - Arthurian or other medieval scenarios with mock combat. Basically theatrical play-fighting in knightly costumes.

The big high-culture difference between Italy and the Burgundian world is the relationship with classical antiquity. The North was geographically and historically removed from the immediate legacy of Greco-Roman civilization. This meant virtually no visual influences in the art. It is true that ancient authors were well-known through textual sources. The reality is that antique learning was present throughout the Middle Ages - just adapted into contemporary culture. And not with the humanistic obsession with "purity".

The Four Evangelists from the Aachen Gospels, around 820, miniature on parchment, Aachen, Cathedral Treasury Gospels, f.13r

The court of the Frankish king Charlemagne launched the first "revival" of ancient culture. Hence the common name Carolingian Renaissance. The reality is more the emperor's conscious effort to enculturate his Frankish and other Germanic subject along Roman lines.

The Evangelists are self-consciously classicizing in costume and pose. Likewise the landscape and four beasts of the tetramorph - early Christian symbols of the Gospels. The style clearly isn't ancient, but derivative enough to see the connection.

There are different points in the Middle Ages where classical influence bubbles up. The 12th century is another well-known example. But on the whole, these are not the visual norm - it's why there has been a tendency to call these periods "renaissances". But on the whole, that humanist interest in ancient culture on its own terms is not the same kind of factor north of the Alps until into the 16th century.

Consider this illumination from a mid-15th-century manuscript of the Alexander Romance - an Old French romance based on a fictionalized life of Alexander the Great.

Sanson of Ailly delivers his message to Nicolas King of Armenia, from Jean (Jehan) Wauquelin's Le Roman d'Alexandre, vol. 1, 1447, BnF Français 9342, f.16v.

No interest in historical accuracy at all. It's a French chivalric tournament. This is what we mean by virtually no visual influences. And it's contemporary with Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden in painting.

The same holds for actual ancient authors and not just medieval fan fiction. Here's an illumination from an anthology of ancient Roman authors compiled by a French writer in the middle of the 15th century. It's described as a history as a history of Rome from the founding to Constantine, abridged from Livy, Lucan, Orosius, Suetonius and others

Caesar crosses the Rubicon from Jean Mansel's La Fleur des histoires, vol. 2, 1454, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, MS 5088, f.192v, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Note the similarity in date and style between these last three illuminations. The same retro-medieval chivalric type of depiction whether a contemporary event, a medieval legend, or an ancient history.

Without the same tie to antiquity, there was no comparable significant early humanism movement either. Certainly nothing like the one sparked by Petrarch. Classical humanism does spread north – the Reformation is essentially a Christian humanism movement. Consider the basis in the original textual sources. It just lacks the overlays of imperial papacy and Hermetic Neoplatonism found in the Italian version. But it comes later, and as the relative lack of Neoplatonism and Hermes suggests, is far less obsessed with ancient Rome and Greece.

The art is therefore not really “Renaissance” in that there is no ideology of “rebirth” involved.

So why Northern "Renaissance"?

It appears that 15th-century Netherlandish art gets that name because it was contemporary with the Italian Renaissance. That's it. When the official modern art narrative was expanded from Italy to the rest of Europe in the 20th century, the name got transferred because of the time period and prestige.

Seriously.

Pioneering historians of art Erwin Panofsky and Max Friedländer simply called it early Netherlandish painting.

Panofsky's influential book of that name introduced the subject to English world in two volumes in 1953. Friedländer's more extensive 14-volume study appeared in German between 1924 and 1937, but was only translated into English between 1967-1976. Neither saw fit to use the term Renaissance.

So why all those Northern Renaissance books?

What seems to have happened is that within beast academic circles, narrative huffers were butt hurt that Italian art was “privileged” over Netherlandish “primitives”. So the word Renaissance was misapplied to counteract this perceived terrible value judgment. In other news, “academics” have always been infantile to the point where deliberate falsehood is preferable to hurt feelings. Still wonder how “higher education” became such a cesspool of beast nonsense and idiot word magic?

There is visible change in the leading artistic circles of the Bergundian domains. It just isn’t steeped in Classical ideology. It's coming from a different place initially.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Altar of Our Lady (Miraflores Altar), around 1440, oil on wood, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

What is does bring is lurid oil color and attention to detail - enhanced realism and emotionalism. Intensified elements we've already seen in the Gothic. There's even some International Gothic luxury. Oil paint debuted in a serious way in the north, and that allowed for bright and subtle color and fine detail.

Close-up of Jesus' appearance to his mother. The vivid colors and bright landscape are typical of 15th-century Flemish oils. Note how Jesus stands in a way to show the wounds - to show that he is risen but also to let people empathize with his suffering and triumph.

Also note the Gothic - not Classical - architectural details in the room and around the perimeter.

Pointing out the emphasis on surface realism in the North as different from Italian idealism is another commonplace. There is truth to it, but it's hard to look at the painting right above without wondering where the hyperrealism is. That's the problem with making up forced binary definitions - non-universal distinctions are presented as universal. Where the "northern realism" does come up is mainly in the work of Van Eyck initially, then in the development of particular genres. Landscape, still-life, and portraits are all non-Italian developments that connect painting to subjects from more prosaic life.

This painting is most often shown as an example of Van Eyck's realism. Two things stand out - other than the idea that Putin is centuries old. The attempt to capture a real likeness "warts and all" as distinct from Classical portrait idealism. And the detailed rendering of real fabric in the red turban.

The caveat is that there is a reason this portrait is often shown - it's the most shockingly realistic of Van Eyck's people. We also see the Italians painting "warts and all" within a half-century. The point still stands - just not as the universal rule internet lists present.

Still-life is another Flemish invention that is built on everyday reality. As a portrait is a careful depiction of a person, a still-life carefully depicts an inanimate object. This painting by Memling - a dominant artist of the post-Van Eyck and van der Weyden generation - is the earliest we've found. It is certainly attentive to realistic detail. But look closely before reading on. Can you spot something less prosaically "real"?

Hans Memling, Flowers in a Jug, around 1485, oil on panel, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

It's the symbolism. According to the museum website, the maiolica jug has Christ’s monogram and the flowers refer to Mary. Lilies refer to her purity, irises to her as Queen of Heaven and mater dolorosa during the Passion, and aquilegias are associated with the Holy Spirit. This ties into the nature symbolism common throughout the Middle Ages, where plants, animals, gems, etc. were credited with abstract meanings.

The maiolica and the Eastern carpet are signs of commercial wealth. This is an intrinsic internal contradiction to the spiritual message that will become more and more significant.

The museum site also notes that how this painting was originally presented is a mystery. Was it the wing of a triptych like some shown above or part of a diptych? The problem is that these multi-part paintings were later broken up for sale to collectors after the culture changes and the art market picked up. It's improbable that it was free standing. Especially considering that there is a portrait painting on the opposite side. Triptych wings and diptychs were painted on both sides so they showed a picture whether opened or closed.

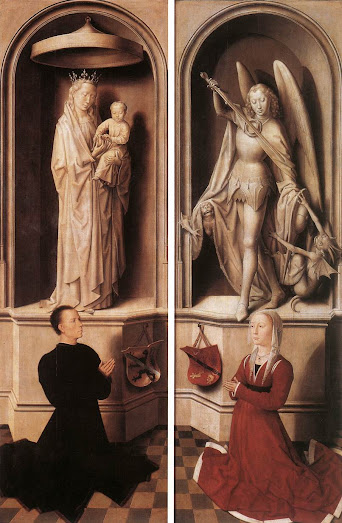

Here's what Memling's Last Judgment from earlier looks like closed. It's very different from the phantasmagoric open Last Judgment with it's colorful angel and vivid afterlives. Keep in mind that the wings were usually closed.

Hans Memling, The Last Judgment Triptych (closed), between 1466 and 1473, oil on wood, National Museum

Some important features...

The patrons or customers are shown in prayer with family symbols. Worldly status matched by piety.

The Madonna and Child and St. Michael are shown as monochrome statues. When the doors are closed, they show how real people in the world know holy figures - through representations of the kind found in churches. Less real than the flesh and blood worshippers.

When the wings are open, the spiritual reality that the statues and devotions represent are "shown". It's obviously all representation, but there are levels that correspond to metaphysical relationships.

Hans Memling, Portrait of a Young Man praying, around 1485, oil on panel, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

This is on the other side of Memling's Flowers in an Jug. Remember - the museum says the original configuration is unknown but it certainly looks like one wing of a triptych or half a diptych. If so, there would be a scene opposite showing what Mr. Supercuts is visualizing. If so, the vase would be shown when the painting is closed. A symbolic real-world thing that points to the sacred mysteries inside. Maybe.

The point isn't an impossible recreation. It's that clear distinctions like real or idealized don't really hold up.

That's worth repeating - clear distinctions like real or idealized don't really hold up in this climate. This is the world of the Devotio Moderna and Besloten hofje. A world there the sacred and secular intermingle and people desperately try and get closer to the former. Which helps us get a handle on a painting like this one by Van Eyck again.

The items on the self and the fabrics that the Madonna sits on are taken as signs of his realism. Likewise the natural mother and child act of nursing. But look how big she is in the crowded space. What kind of room is this? Where are they? Note the symbolic animals on the throne, and how the arched shelves and window balance. It feels real in detail, but very artificial overall.

Jan van Eyck, Lucca Madonna, 1437, oil on panel, Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Does the closed space relate to the idea of the closed garden at all? What do the objects mean? They seem ordinary, but are rendered with great care and prominently placed. How about the oranges on the window ledge?

We don't know the answers and couldn't find an easy explanation online. But it is obvious that "realism" is only part of the story. If anything, the realistic detailing only makes it harder to separate the "real" and the "supernatural".

So instead of realism, realizing may be a better choice of term. At least for the way the spiritual is made tangible and allegory blends with the natural. The same holds for the supernatural sides of the Gothic legacy - whether the beautiful or horrifying.

Take a look at Van Eyck's small but insanely detailed version of the Crucufixion and Last Judgment diptych. Each panel is less than two feet high!

Jan van Eyck, Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych, 1440 –41, oil on canvas, transferred from wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art

It's small, but look at all everything that's in there. Start with the Crucufixion side.

The tormented, suffering body of Christ intended to create empathic connections. Note the scrawny body, anguished face and gushing blood. The thief isn't doing so well either. Quite unlike what you'd expect to see in mid-15th century Italy.

Hard to reconcile with a universal tendency to realism like the portrait in the turban. More vivid than "real".

The hideous mocking figures are another bit of painted rhetoric - things intended to trigger emotional response. Looking at them is supposed to create loathing. For them and for their sinful natures.

This also appears more "Gothic" than "Renaissance" if we go by the standard narrative.

For a contrast, here's the same subject from almost exactly the same time from the top painter in Florence. It's not without emotion - the subject is inherently emotional. Plus it was painted for a Dominican convent where the friars were expected to use it as an aid for their own devotions. But there is a respectful decorum for the body that blunts the raw visceral power of Van Eyck's. Not stylistically classical, but with a classical humanist spirit. Note the overall sence of balance and relative static nature of the figures - even the mourning ones.

The difference is hard to pin down in words, but easier to see. We suspect that this is the obstacle for the narrative attempts to make simple binary distinctions. The answer is to not make simple binary distinctions.

Fra Angelico, Crucifixion with Saints, 1441, fresco, Museum of San Marco, Florence

Back to Van Eyck, the vision of death and the damned in Hell is pure Gothic horror. A visceral fusion of Biblical language contrasting eternal life in Christ to death and medieval visions of hellish torment. It is true that the Bible mentions the everlasting fire on a number of occasions. Matthew 25:41 is a fine example - "Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels".

But over the Middle Ages, terrifying descriptions of Hell as a fiery, demonic place of torment become an increasingly significant part of "Christianity" as representational complex.

The winged, skeletal death figure as the divider between the resurrecting dead on earth and Hell below is a uniquely effective way to show this. The abundant torments of the damned work like any devotional image - repetitive variations of eternal horror to meditate on.

Unfortunately Christ the Judge and the heavenly group appear to have been painted by workshop assistants. The quality is obviously much lower. But the colorful archangel is a phantasmic vision that foreshadows Memling's last Judgment up above.

Where's that superficial "realism"?

Lurid, vivid, but not real like the details around Van Eyck's Lucca Madonna. Or some of his devotional pictures where the idea clearly is to break down that division between human worshippers and spiritual realities.

Jan Van Eyck, The Madonna with Canon Van der Paele, 1436, oil on canvas, Groeningemuseum, Bruges

This is superficial realistic by medieval standards, but we are not to believe these figures are all physically together. It's that the subject of his devotion are close - as if right there.

So to be fair, there is a "realistic" dimension to Netherlandish art relative to Italy. But not the representation of material reality in modern terms as a priority. What it all shares is the desire to make spiritual truths as vivid as the world before our faces. It's sensory impact as a metaphor - a means of "realizing" higher realities that are not directly accessible to our senses.

Put in terms of the ontological hierarchy, it's a way to represent abstract or ultimate reality in materially perceptible ways.

The ontological hierarchy is the Band's representation of the relative natures and interactions between levels of reality. It was worked out over a number of posts and represents the what we can know and how we can know it. Onto-epistemological hierarchy is more accurate, but too awkward and obnoxious in an academic jargon-sounding way to be effective.

It's a rough outline, but invaluable for avoiding the endemic category errors in knowledge claims that have plagued a lot of "thought" and led directly to modern and postmodern inversion.

The states beyond empirical discernment can't be empirically discerned. The Netherlandish painters are putting them in forms that can, with maximum rhetorical impact.

And it better accounts for Van Eyck's younger contemporary van der Weyden - the other big name usually connected to the "Northern Renaissance". We've seen enough of his paintings to note that Van Eyck's surface realism doesn't apply in the same way. But we do get the lurid color and intense emotion that make religious subjects seem immediate.

This painting is a really good example of bringing the material and spiritual together and making you confront it. Remember that late medieval drive to get closer to the representational complex that made up contemporary Christianity. Here the Seven Sacraments - themselves a medieval representation - are depicted inside a Gothic church surrounding a Crucifixion scene.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Seven Sacraments, 1440-1445, oil on panel, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Now, consider the actual history of the seven sacraments.

Sacrament simply means mystery - at least according to Oxford Languages. Before the 12th century, Christian writers identified various numbers of rituals under this name [click for a link]. It was Peter Lombard - a prominent 12th-century theologian who appears to have been the first to definitively declare seven in number.

The Catholic attitude towards dogma is often misrepresented - it's more accurate to say dogmatizing something formalizes existing ritual practice - tradition - instead of willing it into existence. This doesn't change the fundamentally representational nature of the action, but does recognize tradition as the source when claiming abstract reality inheres in material things. Obviously an article of faith, but not as arbitrary or incoherent as opponents often claim. We aren't sure how the early Christian concept of sacred mysteries codifies into seven sacraments, nor do we care enough to search deeply. The 13th-century Fourth Lateran Council formalized Transubstantiation - immensely important for late medieval piety. The 16th-century Council of Trent provides a clear confirmation of the official seven sacraments.

Back to Rogier...

Here's the Eucharist - positioned as the central sacrament of the seven and placed next to the Crucifix - the body of Christ - that it becomes. Note the elaborate sculpted altarpiece behind the priest. The figure of the baby Jesus makes another direct connection between the corpus and the host.

The premise that the Eucharist manifested Christ's actual body and blood made it a theophany - and the most visible sacrament in late medieval devotion. Consider - if the driving force was getting closer to the sacred, a transubstantiated host would be the best option. The late Middle Ages are full of Corpus Christi processions, stories of bleeding hosts and other miracles, host venerations, more and more compelling tabernacles to hold it, etc.

It's easy to see Rogier's altarpiece - sort of a meta-altarpiece given the Eucharist at the altar within it - as strengthening the connection between the ritual and the believers. Consider that the formal notion of seven distinct sacraments was relatively recent. And that people were already fixating on them as ways to bring the sacred into their lives in a more immediate way. Then there's the interior - exactly the sort of church setting that would be familiar to 15th century Netherlandish Christians in the most urbanized part of medieval Europe. Together you have the imaginative devotional presence of the Crucifixion, the ritual presence of the sacraments, and the interior presence of everyday churchgoing, filled with people in 15th-century clothing. The abstract-spiritual and material realities combined in a way that's accessible to the senses.

How is this kind of painting any different from the visceral desire to get closer to the sacred in prayer and other expressions of piety? From devotional activity built on touching, seeing, visiting, and visualizing?

It isn't.

The blend of visceral rhetoric and and religious allegory in the 15th century can be hard to tell apart. That's the point. It's depicting a unified world view where the sacred and material are one. If we want a brief contrast with Renaissance Italy, that works better than "realism" defined as proto-modern materialism. So long as we limit it to the Netherlandish holdings of Burgundy at first. So spiritual realism vs. humanistic classicism as a rough starting distinction. Well, that and the weird ugly figures.

Much like Renaissance Florence, Netherlandish art innovations spread to neighboring places. Bright colorful detail, intense personality religiosity, and weird ugly figures.

Simon Marmion, The Lamentation of Christ, around 1467, oil on panel, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Like this French painter who actually worked for the Dukes of Burgundy among other patrons. Note how Jesus' body is positioned in a way that is totally unrealistic as a physical event, but perfectly displayed for the viewer to meditate and reflect on.

He's not as polished as the Flemish painters like Rogier, Van Eyck, or Memling, but working in exactly the same idiom.

Konrad Witz, Annunciation, 1437-40, Germanisches National Museum, Nuremberg

Or an ugly German take on the Annunciation in a contemporary interior, likewise without the polish. The idea being to make a Biblical event identifiable to 15th-century people.

The clothes look like they could have been painted by Rogier's less talented brother.

When we do see signs of Italian Renaissance influenced classical features they're oddly grafted on to a Flemish substructure. It's a mercifully short-lived phase, but easy to see in comparison to the paintings we've been looking at. Jan Gossaert stands out for this, but there were others. The gravitational pull of the High Renaissance was undeniable, especially as classical humanism spread north in other areas of culture.

Jan Gossaert, Adam and Eve, around 1507-1508, oil on panel, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

Note Gossaert's interest in classical nudity. Eve is more attractive than the usual ugly Netherlandish women and in the pose of a classical Venus. Ripped Bob Ross Adam is a muscular contrapposto figure of the kind we haven't seen here. Hardly something you'd swap a Raphael for and lacking even the mystic appeal of Van Eyck, but a good demonstration of change.

Probably Bernard van Orly, formerly attributed to Jan Gossaert, The Virgin of Louvain, around 1520, oil on panel, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Another sign is the replacement of Gothic architectural settings with fantastical classicism. The mediocre composition of this painting does a good job of showing the contrived, imported nature of the new aesthetic within an established stylistic idiom. Note the realistic detail of the flowers at the front and the symbolic animals - as much a sign of the Netherlandish tradition as the poor grasp of Classical form and proportion.

When the Reformation hits, the cultural landscape changes radically. Luther’s theses spawn a rapid proliferation of sects that transform European religious practice before the continent plunges into a century of war and strife. As with any huge historic shift, the causes are multiple and interrelated. The obvious corruption and inversion of the Church that we've considered earlier in this post and in the previous few was an important immediate one.

Interpretation of Bramante's 1510s plan for new St. Peter's basilica

Indulgence-peddling was particularly egregious. Especially given the purposes for intensification – building a massive Babel-like temple the new St. Peter’s in Renaissance style atop the ruins of Constantine’s basilica.

As megalomaniacal as Julius was, the argument could be made that his rabid materialism was a misguided attempt to glorify the Church. His successor – and Luther’s counterpart – the aforementioned Medici Leo X could make no such claim. He was pure court hedonist and son of the famous Lorenzo the Magnificent – the same aristocrat who drove Ficino to translate Hermes in our occult posts. In fact, the young Leo was educated by Lorenzo’s court humanists, including Ficino and others. Probably arch-synchronist Pico della Mirandola and Agnolo Poliziano.

Leo ran the Vatican like a princely court. While Julius was personally parsimonious, Leo was profligate. Given to feasting, courtly hunts and games, and art collecting among other pursuits. When Luther took his ill-fated pilgrimage to Rome, it was the Rome of Leo that he saw. This was the climax of materialism and corruption that triggered his decision that the papacy was irredeemable.

It’s not a far-out decision. A late medieval history of imperial aspirations, self-idolatry, schism, then renewed megalomaniacal materialism sum up the preceding couple of centuries. Even a cursory reading of scripture indicates the inversive and often outright evil nature of this representational complex. But identifying a problem and determining the correct solutions are not the same thing.

Plastering the Sistine Chapel with naked men because "classical" probably didn't help.

Other factors are more subtle. The same schism we just mentioned was driven by monarchical politics. In particular the machinations of the King of France. It’s no coincidence that the papacy relocated to Avignon, and that the Avignon popes refused to cede power once Rome was restored. Treating the papacy as a political football was a direct consequence of the developments covered in our earlier render unto Caesar posts.

Blurring the lines between Church and monarchy was a dagger blow to spiritual authority.

Unknown artist, after Holbein, The Family of Henry VIII, around 1543-1547, Hampton Court Palace

This becomes apparent in a Reformation context when blasphemous obscenity Henry VIII declared himself a spiritual authority.

Here's a familiar pose, only instead of a gentle Madonna on the luxurious carpet, it's an obese serial murderer.

Then there is that larger social direction. That unrequited desire for an ever-more personal Christianity that was a subtext of this post.

And what’s the personal but solipsism?

On the one hand, it is easy to see how the late medieval system could lead to spiritual insecurity. Luther’s simple method of justification by faith cut through the complex web of ritual and priestly corruption with a reassuring message of salvation. One built on Jesus’ own words in scripture and not towers of spurious medieval addenda. While bypassing the increasingly intense drive for visceral devotion that clearly wasn't meeting the public's spiritual longing.

Arm Reliquary, around 1230 from the Meuse Valley, South Netherlands, silver, gilded silver, niello, and gems; wood core, Metropolitan Museum of Art

A reliquary was a case for the display of relics - this one has windows to see the saint's bones. The blessing gesture allowed the priest to hold it up as if the actual saint was blessing the adoring crowd. It's designed to blur the divide between material and spiritual, representational and real - like an even more visceral version of a Netherlandish painting.

A lot of pilgrimage was idolatrous. Many relics were fake, as Chaucer noted. Snake oil was abundant. In terms of sociological history, the Reformation is a logical outcome of the Modern Devotion and other forms of personal, affective piety.

This is where representation comes in - not just art, but Christianity itself as a representational complex.

Consider Luther’s famous “priesthood of all believers” and the idea of sola scriptura. The idea is to put the Bible into Christian hands and allow them to apply what is there directly to their lives. Sounds good. Then where does the authority of self-idolators like Calvin - let alone Henry VIII - to blend and usurp God's and Caesar's come from? The Bible tells us that we judge by the fruits. While the Reformation deserves credit for spreading the Gospel, it also became a vector for self-declared spiritual authorities to claim absolute power.

Where does the authority come from? The self-idolatrous "authorities" claim it for themselves.

In this "Reformation" altarpiece, leading reformers usurp the roles of the Apostles at the Last Supper. That is, precisely what they weren't.

And when the “leaders” directly contradict sola scriptura, should there be a shock when the flock does as well?

What was positioned as a return to founding values gradually morphed into a license to do as thou wilt. So long as you have a "church". This isn't interpretation - a cursory glance at the leading Protestant denominations today is enough to indicate that it's what happened. Of course there are exceptions. There always are. But that gate is narrow. And the core problem - apart from the fallen nature of man and the world - has proven consistent with Christianity of any denomination. Onto-epistemological category error.

Either the Bible is accepted on faith as divinely inspired, or it isn’t.

If it isn’t, what authority does it have?

If it is, on what grounds does one claim the right to pick and choose which parts to follow and which to disregard?

It's not complicated. It's just not a ticket to worldly power. The next Arts of the West post will look at the aftermath of Reformation – and Renaissance – in the later 16th century.

Until then, here's another look at that visceral spirituality designed to connect directly and emotionally. The direct face-to-face appeal is especially powerful. It didn't get the job done, but is an important chapter in the Arts of the West.

Unknown, Christ Carrying the Cross and The Crucifixion, 1494, oil on panel, Atlanta, The High Museum of Art

No comments:

Post a Comment