If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction and overview of the point of this blog that needs updating. Occult posts like this one - posts on the history and meaning of occult images - have their own menu page above. All posts are in the archive on the right.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry.

Thomas Cole, Prometheus Bound, 1847, oil on canvas, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In the last occult post, we started looking at the mythic Greek character of Prometheus and his relevance to the occult. What we found was an inverted value system where divine authority was malevolent and the rebel a mistreated hero. Maybe. It was ambiguous.

This consisted of recapping some basic ideas of the occult posts for new readers, then considering his first appearance in the works of the archaic poet Hesiod. Click for the link. If you're curious about what we are doing or where Prometheus came from, that's a good place to get caught up. Because this post will skip the recaps and jump right into Prometheus in the ancient world after Hesiod and see how he evolves before the end of antiquity.

Prometheus Creating Man in the Presence of Athena, fresco from a Roman, 3rd century AD, Museo della Via Ostiense, Rome

Like the weird notion that Prometheus was the creator of humanity and not just a benefactor.

This will be a big step towards his use as an replacement for traditional Western Christian imagery in by de-moralized, self-worshipping Modernists. Even Lucifer doesn't get held up as a creator.

The important thing to remember about Greco-Roman myth is that there was no canonical version of the legends and stories. What little we know about the nuts and bolts of their religion tells us that these were oral traditions - mystery cults passed down through ritual and initiation without standardized holy scriptures. This means we have to deal with big variations in the surviving historical record that scholars of Christianity or other scriptural religions don't have to deal with.

Votive plaque from the Eleusian sanctuary, 4th century BC, painted terracotta, National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The Eleusinian Mysteries connected to the cult of Demeter and Persephone was the most prominent Greek cult - along with the Dionysian ones. The origins and details are unknown but the cult was very ancient and continued into Roman times. The basic premise that the descent and delivery of Persephone from the underworld symbolized devotees' own hopes for the afterlife.

Here, Demeter welcomes the torch-bearing initiates during a nocturnal ritual

Marble statuette of Kybele, 1st–2nd century AD, Roman marble, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

One thing that we do know is that statues were commonly used as devotional objects and stand-ins for the deity. This is a big reason why early Christians were more tolerant of painting and other 2D images than sculpture. The paintings didn't have the same connections with the local history of pagan worship and idolatry.

Kybele was an Anatolian earth mother goddess worshiped in Athens by the fifth century BC and remained popular through pagan antiquity. Without scriptures or other written records it is hard to say much more.

Scripture is no proof against disagreement because passages are open to different interpretations. Catholics and Protestents famously disagree about Christ's charge to Peter or the Petrine succession. That is, whether Jesus singled Peter out from the other apostles to lead his mission after his ascension. It's a complicated debate not worth getting into here, so we'll just look at the most commonly-cited passage in defense of the idea.

Christ Presenting the Keys to Saint Peter, 1315–20, German stained glass, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The presentation of the keys was symbolic of giving authority. The Catholic interpretation is made clear by Peter's papal tiara and pallium that show he is pope.

What differentiates this from the variability of Greek myth is that both sides accept the canonicity of the same passages and the same characters. There aren't alternative "Christian" oral dogmas where Jesus isn't the Son of God, or Peter isn't an apostle. The Bible provides a narrative base - argue over interpretations, but change the stories and what you have is no longer Christianity.

The shifting nature of Greek myth means that the equivalent of changing who Jesus or Peter are happens often. But it's more confusing than that - there is no canonical, word of God-level foundation to change.

Gustave Moreau, Hesiod and the Muse, 1870, oil on canvas, Musée Gustave-Moreau, Paris

Jump forward to ancient Rome, where Greek myths were taken up into Roman religion. The most historically influential Roman source for this stuff was probably Ovid's Metamorphoses - they retell a lot of familiar stories from Hesiod and other Greeks. But Ovid was a commercially-successful professional poet and writer best known for erotic themes. There is no religious authority hanging from him at all. And when he recounts Hesiod's Ages of Man, he simply omits the Heroic Age. It works better from an artistic perspective to name all the ages after metals, but it's blasphemous if there was any concern for religious accuracy.

Jose A. Fadul, Gift of Fire, watercolor, 2008

Long story short, there are many versions of Prometheus and the other myths, with no way to weight them for their contemporary religious significance. Instead, what historians have to deal with are centuries of post-Classical "interpretations" where writers of all kinds picked and chose the versions that best suited their own agendas.

This means that Prometheus had the cultural and historical heft that came with "antiquity" in the post-Classical West, but no fixed, canonical identity like Jesus or Peter. Or the Buddha or Mohammed to Buddhists and Mohammedans. There is no one official source to go to.

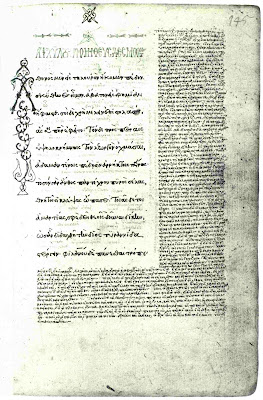

The beginning of Prometheus Bound, first half of the 15th century, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Cod. Phil. gr. 197, fol. 145r.

We see this in Prometheus Bound, the next major Greek treatment of Prometheus. This play was traditionally credited to the great dramatist Aeschylus, although modern scholars doubt the attribution for what seem like sound reasons. The authorship is less important that the text for our purposes, though it should be pointed out that centuries of belief that Aeschylus wrote it definitely raised the historical status of the poem.

Click for a prose translation, and a free verse version.

Aeschylus, Roman copy after a Greek original of the 4th century BC, marble, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Aeschylus (525/524-456/455 BC) was known as the Father of Tragedy and was the main figure in elevating Greek drama to the artistic status it enjoyed since. He was an innovator in writing and staging and an author of tremendous power who was a perennial winner at the big Athenian dramatic festivals. If you're interested in the spare, harsh majesty of Greek tragedy, his Persians and Orestia trilogies are absolute masterpieces.

Having his name on a play approaches Shakespeare as an authorial imprimatur.

Prometheus Bound makes serious change in the nature of the characters from Hesiod. We observed that Hesiod's Zeus was a tyrannical a-hole if we take the stories at face value. But we also noted that if we accept Zeus as a symbol of authority, then Prometheus becomes the gamma a-hole - an arrogant sneak who puts his own desires over the divine order of reality. The latter is actually probably closer to Hesiod's feelings. Prometheus Bound doesn't give us any comparable ambiguity. It is crystal clear in the text that Prometheus is the cruelly abused victim and Zeus the monstrous tyrant.

John Flaxman, The Binding of Prometheus, first published in Richard Porson's 1795 translation of Aeschylus's Prometheus Bound

The play is not up to Aeschylus' standards - if he did write it, he was drunk or failing mentally. Nothing really happens - it opens with the gods of power and strength shackling Prometheus to his rock with a chain forged by Hephaestus, the smith of the gods, and the rest of the story unfolds with him hanging there.

Gustave Doré, Oceanides (Naïads of the Sea), between 1860-1869, oil on canvas, private collection

The whole thing is passing characters talking to him until Zeus hits him with a thunderbolt for refusing to reveal information and he sinks into Tartarus. Like the sea nymphs who serve as the chorus in the play. You can see the eagle in the background.

No Pandora or sacrifice-trick as in the Theogony.

Supposedly the play was part of a lost trilogy - Prometheus Unbound and Prometheus the Fire-Bringer or Prometheus Pyrphoros being the other two so there may be more to this narrative. Many Greek plays were composed in threes to tell a more substantial story than the limits of one performance would permit. Only fragments of the others remain, but the consensus is that they tell of Prometheus' torments, his deliverance by Hercules, and his ultimate reconciliation with Zeus. But these don't survive, and don't have the influence of the first. O

n its own, Prometheus Bound is a literary dud. The only argument for its prominence is the idea of rebellion against divine authority inverted into a noble struggle against tyranny - the sub-mediocre writing can't explain it. So look at the ideas:

Gusten Lindberg, Prometheus brings Fire to Mankind, 1897, marble, Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm

Deceivers liken Prometheus to a Christ-figure because he is a "savior" who suffers for man. This is an asinine misunderstanding of Christian metaphysics. Zeus - in the play and elsewhere - is not a creator. He is a sadistic usurper whose priorities are clinging to power and feeding sadistic appetites. He fits the lying misrepresentation of the Old Testament God as a capricious tyrant sometimes offered by humiliatingly stupid "atheist" window-lickers, but is an inversion of Christian divinity.

If the word "Christ" has any historical or literary meaning, Prometheus literally is not a Christ figure.

The motivation for Prometheus' rebellion in the play is to save humanity from destruction by Zeus. Supposedly he not only gave us fire and taught us all the arts of civilization - writing, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, metallurgy, architecture and agriculture - he somehow thwarted Zeus' plan to wipe us out. This undeveloped claim further strengthens the inversion Christian metapysics - as ultimate reality, God's plan can't be thwarted. The attempt to thwart becomes part of the plan. And God's own redemptive sacrifice in the form of his divine Son is the central part of it. Prometheus may be heroic in this story, but the cosmic turd he opposes is diametrically opposite Christian divinity on every ontological and moral level.

Prometheus and Io from Prometheus Bound, directed by Terry McCabe, April 27-June 10, 2018, City Lit Theater, Chicago

Events are added to the myth to make Zeus more unambiguously vile. Supposedly Prometheus used his gift of foresight to help the gods defeat his brother Titans, making Zeus a betrayer as well. Imagine a "divine" authority from a Christian persepective that needs an older, weaker being for guidance. Then there is the visit from Io - Zeus' "lover" and torture victim. She was turned into a cow, supposedly to hide her from Zeus' sociopathic sister and wife Hera - they were incestuous as well as sadists - but Hera has her chased endlessly by biting flies. Prometheus foretells that her descendant will free him, as Hercules ultimately does.

Imagine how terrible this performance must have been. The review describes cow-girl's: "erratic yelping, the constant swatting of her long cow tail (held in the hand of the actress), and her spasmodic leaps from center stage to the platform of Prometheus' crag, Io wears down the audience with her unnerving and continuous convulsions." It's more entertaining to imagine how much money you'd have to be given to attend, and how much more to stay to the end.

Hermes and Prometheus from the same gem

Then the closing event - where Prometheus refuses to tell Hermes which of Zeus' rape babies will ultimately overthrow him and is sunk into the earth.

Forget about divine plans and metaphysics - this cosmic joke lacks even the foresight of a carnival seer.

It is surprising when you actually look at Prometheus Bound to realize how irrelevant it is as a metaphor for anything in the West. If there is one thing we know about evil is that it can't create. Hopelessly cut off from the Truth that is the wellspring of Beauty, all it can do is twist, debase, and distort. That is, project it's own perverse nature onto things that actually are real.

The risible notion that this Prometheus is somehow meaningful to the Christian West is exactly this kind of a projection. The pretense that Zeus is anything other than the inverse of rightful divine authority betrays gross ignorance, severe cognitive impairment, or bold-faced lying. Or perhaps all three, since all apply to the way that atheists and other narcissistic lying satanic idiots spew the bile of their internal corruption onto those things that most surpass them.

Plato's Academy, 1st century BC Roman mosaic from Pompeii, Museo Nazionale Archeologico, Naples

It's fake Aeschylus' version more than Hesiod that shaped later conceptions of Prometheus, but there isn't the same richness as Hesiod's more open protagonist. The idea that "divine authority" is a monstrous evil is implicit in the story - it makes no sense without it. This is where the appeal to mono-dimensional satanic modernist idiots comes from. The whole notion that humanity is the master of the universe - that the Band refers to as secular transcendence in regular posts - requires the fiction that natural orders and higher philosophical realities are somehow "oppressive". Read that again, because it is so mindless that the abject vanity and stupidity can slip past on first reading.

And just like that, we are face to face with the satanic inversions of modernism. It is exactly the same relationship as luciferianism - just a little more metaphorical. Rather than using the fake "morning star" as a the icon of ignorant narcissism, you just project the twisted metaphysics of a second-rate play. The literary quality is as irrelevant as the metaphysical legitimacy of Lucifer. What matters is that the auto-idolators have a masturbatory hero to pit against, logic, reality, and metaphysics.

BacchusResurrexit, Prometheus VI: Lucifer

Light Bringer, Fire Bringer - it's like there's a pattern...

Plato manages a more intelligent transition from myth into allegory. It is clear from his dialogues that he had little interest in the traditional gods or mystery cults, but did use them as symbols and metaphors for philosophical things. We can see this thinking in the structure of the cosmos in late antiquity, where the planetary spheres were given names corresponding to the Gods. We still use the Roman versions like Jupiter (Zeus) today.

Dietrich Meyer, Septem Planetae (The Seven Planets), early 17th century engraving, British Museum, London

From the left: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sol, Venus, Mercury, Luna

Today's second ancient source is Plato's Protagoras, a philosophical dialogue rather than a work of literature or a religious source. The account of Prometheus here is much shorter, just a couple of paragraphs. Here's a link - Prometheus appears in sections 320 and 321. This is where we see the idea that he doesn't just help and teach mankind, he is part of the creation of it. The story is that the gods form man and animals - mortal life - from clay and fire and charge Prometheus and his idiot brother Epimetheus with doling out the different attributes that will define each and allow them to survive. But because he is stupid, Epimetheus gives away all the provided attributes before getting to man. Prometheus is compelled to steal additional gifts from the gods lest naked, defenseless man die out.

Prometheus teaching man how to use fire, Liebig card, from a series on the legend of Prometheus, published in late 19th or early 20th century, chromolithograph

He comes back with the mechanical arts and practical wisdom of Hephaestus and Athena with fire as a necessary element to make them work. These are the "means of life" that we saw in Hesiod in the last post. Only where Hesiod made it a vague allusion, Plato established Prometheus as an archetypal metaphor for human craft and ingenuity.

Noël Coypel, Jupiter in his Chariot between Justice and Piety, 1671, oil on canvas, Palace of Versailles

Notice how different Zeus is as a character from Prometheus Bound. This is exactly the lack of canonical consistency that this post started with.

Plato introduces a different take on the gods. For him, they tend to be allegories or symbols rather than literal superhuman beings to be feared or appeased. Zeus as a more benign divine ruler fits this function, making him an archetype of higher wisdom, just as Prometheus stands for technical knowledge. By thinking of them as allegories rather than real characters, they become familiar analogies for more abstract philosophical concepts.

In this case, we have a hierarchy of gifts:

Caspar David Friedrich, An Owl on a Bare Tree, by 1834, oil on canvas, private collection

Bottom tier:

Physis, or the natural gifts possessed by the animals. In the allegory, they are doled out by Epimetheus. This represents traits that are inborn and not worked for. They may sharpen with practice or experience, but aren't learned.

Heinrich Fuger, Prometheus Bringing Fire To Mankind, 1817, oil on canvas

Middle tier:

Technê, or human creative power, linked to gods through Prometheus. Regular Band posts on the development of the arts of the West have looked into techne as a model of skilled artisanal production.

These are made possible by human intellect, but require teaching and effort. The potential may be there, but there is nothing inherent in them. This is human mastery of the physical world through technology.

René-Antoine Houasse, detail of Minerva and the Triumph of Jupiter, 1706, oil on canvas, Château de Versailles,

Top tier:

Ethos or morality. Plato would have called the arts of civilization something like politikê technê, but what is described in the Protagoras is ethical orientation. It is the "highest" since it comes right from Zeus, but consider what exactly is transmitted. Hermes brings ‘shame and a sense of right’ - that is, the bases of moral living in society.

This connects us to abstract reality - Logos - that is beyond material reality and gives meaning to technê and purpose to human existence. As the metaphor shows us, Logos is a divine gift that exceeds technical know-how.

Plato's version gives us Prometheus as a symbol of our intellectual nature within a more orderly concept of the universe than the chaotic cosmic tyranny of Prometheus Bound. The structure is a hierarchy of values, where human technical ability is recognized as an achievement but still below a higher - in this case ethical - level. There are problems with Plato - he was dishonest and made logically impossible claims about human perfectibility that if followed through would be responsible for monstrous evil - but he did recognize that were subject to a natural order. This Prometheus is less conducive to an occult interpretation since he doesn't really fit with the Luciferian "rebel" against divine evil that we saw in the pseudo-Aeschylus.

But you can start to see the ingredients that would make him the poster boy for modernist auto-idolatry. Consider what happens if self-aggrandizing idiots collectively reject Logos:

Collection of the Museum Strom und Leben, Recklinghausen ‘Prometheus, the bringer of fire!’ (Prometheus, der Feuerbringer), advertisement for a lightbulb with tungsten wire, c. 1910–14

The whole fake Modernist notion of Progress! is based on the inane premise of infinite improvement within a finite system. That our intrinsically material and limited intellects can overcome all constraints and becomes masters of reality. The absurdity of this is obvious every time one of us dies, but the appeal to human vanity and self-importance is too compelling.

Prometheus becomes a symbol of this false belief. In a Modernist sense, that Progress! allows man to replace ultimate reality or God. But this is what Modernism - and Prometheus as a hero - needs you to accept. The lesson, as always, is think before believing the self-stroking blathering of deceivers, no matter how appealing the blather.

Unlike Modernists, Plato could at least think in more than one dimension. He recognized the singular nature of human technê, but also its limitations in a philosophical sense. It's just souped-up materialism, which is why it comes from Prometheus - a lesser being and not "the gods". For this to reach higher, more is needed - something divine or in Plato's case, the metaphysical equivalent of the Forms. Which is why Zeus isn't a cartoon villain like in Prometheus Bound, but a metaphor for this higher reality that gives life meaning.

Plato was pre-Christian, but there is a structural compatibility in his metaphor with Western Christian thought. To make it modern, the divine has to be hand-waved away, and material Progress! or techne proclaimed the be-all and end-all of reality.

Seriously.

The last of our ancient sources is Apollodorus or Pseudo-Apollodorus - the name connected to a Greek work from late antiquity called The Library or Bibliotheca. This work was traditionally credited to Apollodorus of Alexandria, a Greek writer and scholar active in the 2nd century BC, but now believed to be a later compendium from the 2nd century AD.

Apollodori bibliotheca (Apollodorus of Athens, Bibliotheca), mid-16th century, illumination on paper, British Museum, Harley MS 5732, f.1r, London

There isn't much to the former, but the latter is huge. This compendium is probably the single most significant source for the post-Classical Greek myth in the West. Although it is much later than the other authors we've considered, it had the biggest influence in the centuries between the end of antiquity and our understanding of Classics today, with its modern philological and historical analytic tools.

The Creation of Man by Prometheus, 1st century AD, Roman Relief, Louvre.

This is where we see Prometheus become the creator of man - not just someone endowing them, but actually molding them from earth and water. This will become a huge part of his symbolic identity in the post-Classical world.

The fire in the fennel stock from Hesiod is mixed in - but this time as as a means if enhancing his own creation. This is a huge change from the earlier sources we've looked at, and it isn't clear where it came from. The Library is a compilation of accounts, but it doesn't have modern footnotes or sourcing to clarify. We don't even know who wrote it. All we can say is that at some point before the end of the ancient world, Prometheus became a creator. And the huge influence of the Library guaranteed that this would be passed down as one of his main attributes.

Christian Griepenkerl, Prometheus and Hercules, 1878, oil on canvas, Augusteum, Oldenburg, Germany

The punishment and delivery by Hercules follow without much elaboration. The great hero kills the eagle and uses his limitless strength to shatter Hephaestus' chains. Were there any logic in Modernism, Hercules makes a better Christ-figure, since he softens divine judgment and ends the eternal punishment.

Curiously, the Library links Prometheus to the Greek version of the Flood and restoration of humanity by making him the father of Deucalion, the man who with his wife Pyrrha survives the deluge. According to this version, it is Prometheus who warns his son to construct and provision the boat that allows them to survive. This is another change from the older sources that we can't determine the origin. And another place modernist deceivers can invert Christian imagery with "classical metaphors".

Deucalion and Pyrrha Casting Stones, unattributed relief from the Parc del Laberint d'Horta, around 1871, Barcelona, Spain.

This relief shows Deucalion and Pyrrha throwing the stones that miraculously transform into humans and repopulate the world after the flood.

Apollodorus brings us to the end of the ancient Greek Prometheus. Not a comprehensive survey by any means, but add Hesiod from the last post and we've covered the most influential Greek sources. And what we see is a pack of incoherent nonsense - contradictory treatments of the gods and the universe, and a shifting figure given more and more responsibility for mankind. There is no way to resolve these accounts. But that's the appeal. Lying secular materialists' beliefs are equally incoherent. If they cared about historical or intellectual consistency, they wouldn't be lying secular materialists.

Golden Bough, Eyelids of Prometheus, fire dancing performance, 2012

Greek Prometheus doesn't add up to anything rational, but is the perfect figure for the inversion and self-fluffing magical thinking behind de-moralized modernity and the occult. At least fire dancing or fire twirling requires some actual skill and committnemt to craft, putting it ahead of most Modern art.

The fact that he doesn't add up to anything rational may actually be why he is perfect. The occult is based on the denial of empirical, rational, and ontological reality for childish dreams of mastery. It's a commitment to things that are logically impossible because they feel good in the moment, and requires a willingness to switch myths as older lies collapse. To buy in you have to live in a perpetual present, learning nothing from the past but committing to an observably false faith in human perfectibility. In other words, you have to simulate a head injury victim or an actual retard and practice being stupid through repetition, but it can feel good in the moment.

Prometheus Fashioning the First Human, 2nd century BC, carved semi-precious gem, The British Museum, London

What better hero for this infantile do what thou wilt approach to life than an incoherent figment that keeps changing to project whatever magical thought is posing as "knowledge" at the moment?

Who can outwit divinity for no apparent reason and while suffering, comes out on top? Likewise without reason. Who not only "saves" man from the divine order of creation, but actually comes to replace it, because some one said so.

Prometheus Creating Man in the Presence of Athena, painted in 1802 by Jean-Simon Berthélemy, painted again by Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse in 1826, Louvre Museum

The first glimmerings of modern inversion appeared in the Renaissance, when self-idolators arbitrarily declared antiquity culturally superior despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, because secret kings. What matters is that it was successful, and Prometheus rides into the modern West with the full the weight of "humanist" legitimacy.

But that's the self-serving delusion for next time.

Piero di Cosimo, The Myth of Prometheus, 1515, oil on panel, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

No comments:

Post a Comment