If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction and overview of the point of this blog. Older posts are in the archive on the right.

What started as an inquiry into the history behind today’s terrible architecture has followed a winding path to something much more fundamental in the last post: the absurd secular transcendence of Enlightenment rationalism.

A key Band associate asked why spend so much time on something as far from the present as the Enlightenment. The answer is because this is the point in history where the nonsensical vanity that finite human minds could attain metaphysical certainty became the foundation of “elite” culture.

OT: Gabriel de Cool is a great name.

OT: Gabriel de Cool is a great name.

It became clear from the images in the last post that French Enlightenment rationalists jettisoned official atheism for self-parodies like the deification of Newton and the Cult of the Supreme Being. Even the most rationalistic of rationalisms couldn’t overcome the organic bonds of community and the natural human yearning for transcendence.

John Wood the Elder, Bath Circus, 1754-68, Bath, England

Colmar Christmas Market, Colmar, Germany

Which is a more appealing community: the Enlightenment arc or the organic square?

Colmar Christmas Market, Colmar, Germany

Which is a more appealing community: the Enlightenment arc or the organic square?

Claude Nicolas Ledoux, House of the Agricultural Guards of Maupertuis, circa 1780

House in the Cottage Farm Historic District, late 19th century, Brookline, Massachusetts

Which makes for a more humane country dwelling?

Isolate the problem: there is an irreconcilable conflict between loosely defined human nature – individual differences, instinct-driven behavior, organic communal rituals, etc. – and the alien abstractions of centralized authoritarianism. An empiricist, or any mentally healthy individual for that matter, might be expected to conclude that it is not in the human interest to attempt to implement authoritarian abstractions. But there are reasons why the Band calls globalists Satanic.

Rationalist political abstractions may not serve the human interest, but they do serve the interests of sociopathic power seekers, since they offer totalitarianism behind a reasonable façade.

Remember Ledoux’ Royal Saltworks, with the indiscriminate masses and the all-seeing master’s house?

This is the same power structure captured in the famous quote from Orwell’s Animal Farm

Not sure how to make it clearer...

Another fictional character was known for an all-seeing central eye.

The Eye of Sauron, still image from the Lord of the Rings

The potential for despotism in the extreme centralization of power is obvious. Isn't it?

It is important not to lose sight of the fact that in objective terms, evil exists, regardless of one’s religious beliefs, and despite rationalist attempts to dismiss it as mere superstition and prejudice. It seems odd that rationalism's modern descendants in the social sciences have gone even further, seeking to do away with personal moral responsibility. When confronted with an uncertain claim, it is helpful to ask who benefits. This is a variation on the old charge to “follow the money” and is a good way to be attentive to motivations. So who benefits from undercutting moral outrage over evil?

Francisco Goya, Witches' Sabbath (The Great He-Goat), 1821-23, oil on canvas, 140.5 x 435.7 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid

It is not the intention of the Band to wade into the metaphysics of "Evil" as a spiritual entity; the answer to that question falls outside of the strictly empirical approach followed here. But empiricists and Christians agree that in this world, conscious material beings are classified on the basis of their actions; what they do, not what they present themselves as being. The latter is virtue signaling, and is pathetic in its moral cowardice, because only the immoral seek to explain away abhorrent actions with appeals to secret intentions.

Jean Bourdichon, St. Matthew the Evangelist, miniature from the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany, 1503-1508, Bibliothèque nationale de France, stitching and restorations by Jebulon

The Band has cited this passage before because it is such a powerful statement of empirical principle. You are known, as far as others can be sure, by the observable products of your actions. From a strictly empirical perspective, we know evil intentions exist, but they are only verifiable in action, in terms of their effect on surrounding people or the community. How else to separate the imaginary from the actual? It would be surprising if globalists, leftists and other collectivist liars didn't want to blur the line between the imaginary and actual. Their entire world view is based on imaginary wish fulfillment, starting with the solipsistic fantasy that their enlightened minds exceed the limits of human understanding.

Nikolai Yezhov (left) with Kliment Voroshilov, Vyacheslav Molotov, and Josef Stalin, pre-1939. The same photo sometime after 1939.

Of course, the useful idiots all tend to think that they'll in the overseer's house rather than jammed into indeterminate living cubes or buried in mass graves, but their opinions cease to matter once control is obtained over the "rational" structures of centralized power.

Yehzov was the head of the NKVD (secret police), principal executor of Stalin's Great Purge, and a loathsome sadist who lived up to his goblin-like appearance. Yet this was not enough to save him from being purged in turn, after which the Party attempted to erase his memory from existence. There is foreshadowing here for aspiring revolutionaries.

Just more leftist traitors agitating against for the destruction of the nation and its laws.The more you look at the history of the left, the more moronic the "conservative" notion of reasoned debate becomes. So moronic that it rises to the level of treachery itself.

The reality is that "evil" is only manifest in its impact on others. It isn’t vandalism to spray paint your own wall or theft to take your own phone. But this is exactly what leftists seek to remove from the equation. In terms of social harm, what does it matter if was a real demon or a neural quirk caused you to act on dark impulses? Is the suffering of victims mitigated because the perpetrator has been labeled by the medical-industrial complex? Does perhaps being more sympathetic matter one whit to the importance of protecting a community and maintaining levels of order and cohesion conducive to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? An argument can be made for housing the criminally insane in a different sort of facility, but regardless of the particulars, societies where legal and defensive structures that prioritize the care of the wrongdoer are not sustainable other than in totalitarian conditions.

Robert Hooke, Bethlem Hospital, opened 1676, Moorfields, England, anon. oil painting on canvas, 41 x 56.5 cm, Wellcome Library, London, no. 44669i

The West has long known that the mentally ill are threats to society and themselves. Bedlam was not the answer, but neither is pretending it is a form of diversity.

Social "scientists" guesstimate 3 percent of men and 1 percent of women have some form of anti-social personality disorder, so lets use these numbers despite them likely having little bearing in truth, and assume a population average of ~ 2%. Of course, the social sciences are a bit of a liar's club, so the reality is probably wildly different, but even half that number adds up when you think of the number of people you encounter in a given day, especially if you are a city dweller.

As an aside, since the social sciences are committed to dyscivics and ideology, they are neither "social" nor "scientific". A new meta-label is needed for this collection of voodoo and projected wish fulfillment - would guesstinomics work?

CHEKA agents with the body of a torture victim, 1920

Dithering over whether these people are "evil" obscures the fact that their actions certainly are, in terms of impact on their environments. It is a red herring. What is significant is that there is easily enough of them to occupy the nodes of power in a totalitarian regime.

A handful of deviants in an organic community is easily identified and dealt with. Centralized structures become force multipliers for sociopaths, making the absolute centrality of Enlightenment reason a path to absolute tyranny.

Why spend so much time looking at architectural fantasies from the Enlightenment? This is where the globalist ideas were given broad credence, and even after the collapse of the Revolution into a charnel house, the preposterous fantasies floated down the timestream on clouds of human vanity. We can be purely rational. The Revolution was a perversion of true reason, not the logical consequence of attempting to implement something literally impossible as the basis of social organization. And so began the parade of sleazy, self-serving defenses of the indefensible like "real" Marxism.

What sort of person has the most to gain from pushing an acceptance of evil?

By their fruits

you will know

them, indeed.

Lenin and Bolsheviks actually claimed the Jacobins of the French Revolution as forerunners, and they certainly perfected the totalitarian savagery and filthy deceptions of the former. But it was the Enlightenment rationalists pioneered thar globalist method of lubricating the friction between human nature and sociopathic political abstractions with blood.

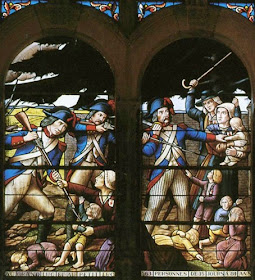

Massacre des Lucs-sur-Boulogne, 1902, stained glass window, Chapelle du Petit Luc, Lucs-sur-Boulogne, France

The Infernal Columns and their scorched earth policy against Royalist rebels in the Vendee prefigured other collectivist attempts to erase a culture. Women and children were especially targeted since they represented future generations.

Leftist academics have fallen back on typical deceptions to explain away what is an inevitable result of centralized absolutism by quibbling over the precise definition of "genocide". What could be the incentive for that?

Lies and reality, collectivist style.

How can you expect anyone advocating leftist positions to be honest, when this is the endpoint they argue for?

Think on that again. The left openly calls for positions that have ALWAYS ended in mass slaughter. Still think it's just a political opinion?

There was a better alternative.

Before moving on, it is important to clear up some terminology. In an earlier post, the Band took up the problem with broad historical periods or categories (click here to read; the discussion of periods begins around the midpoint). "The Enlightenment" is nothing more than a generalization made up by historians, based on certain commonalities in the intellectual culture of the day. It neither existed as an entity, nor was the cause of any event, and its immediate impact on everyday people was much less significant than its importance in cultural history. It wasn't Voltaire gadding about the Paris salons that harvested the lives of the Vendee directly. We are using Enlightenment as a term for a certain kind of idealistic rationalism as well as its logical downstream consequences, since totalitarianism or collapse are the inevitable endpoints of its false precepts.

François Gérard, Emperor Napoleon I, oil on canvas, 230 x 149 cm, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

Napoleon put an end to the chaos after the Revolution, then installed himself as Emperor before conquering most of Europe. His imperialism is a logical consequence of the egalitarian mythology - the integrity of nations is irrelevant - and totalitarianism that were the legacies of the Enlightenment.

Not surprisingly, leftists prefer to represent him as a reaction to the "ideals" of Enlightenment rationalism rather than its endpoint.

Of course, architectural theorists deftly pivot again, with a Neoclassicism now suggestive of Imperial Rome:

Jean Chalgrin, Arc de Triomphe, designed 1806, Paris

The way Neoclassical theory bounced from king, to republic, to empire is a clear demonstration of the lack of any actual substance.

The lesson:

So what's the alternative?

The association of the term Enlightenment with eighteenth-century French rationalism complicates its application to England, where cultural and historical circumstances were different. Here, the roots of globalism took different forms: the elites' disdain for their own culture and the slow transition from nation to empire. If we combine the aristocratic internationalism and imperialism of the English "Enlightenment" with the mechanistic totalitarianism of the French, the possibility of today's global elite come into view.

The different perspectives fit the very different historical developments of the two nations.

The French monarchy emerged in the territory around Paris and gradually assumed control of the surrounding feudal states.

Compare the royal domain in these two maps, one from the eleventh century and one from the fifteenth. The power of the nobility was only fully brought to heel by Louis XIV in the seventeenth century.

The result is that in the most general terms, the pre- modern history of France is one of gradual, creeping centralization of authority. From the destruction of the Templars and Avignon Papacy, to ultimate success in the Hundred Years War, to the absorption of Burgundy, to the suppression of the Huguenots, the major moves all strengthen royal power. At the same time, there is a concentrated effort to create the illusion of an almost timeless French identity.

Royal tombs at St. Denis, Paris.

The royal abbey at St. Denis included a necropolis for the kings of France. This included new tombs for ancient "French" kings, creating the impression of an impressive monarchical genealogy.

Typical of the dyscivic atavism of "radicals", the monuments suffered heavy damage and the remains were profaned during the Revolution. Skillfully restored, they make an impressive group even today.

Jean Fouquet, Coronation of Pepin the Short in 754; Coronation of Charles VI in 1380, 1455-60, from Grandes Chroniques de France, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris MS. fr. 6465, f.76r; f. 457v.

The fleur-de-lys was projected back into the past starting in the thirteenth century. Notice how the kings are almost identical, despite Pepin being a Frank. This creates the illusion of a national culture that is much older than it was.

In broad terms, England's formation was the opposite.

These maps shows the provincial divisions of Roman England, and the main linguistic groups after Roman withdrawal: Gaelic (green), Brythonic (red) and Pictish

Note how these distinctions still align with the main divisions of the British Isles.

Brythonic England did coalesce into several petty kingdoms, but the sort of coalescence seen in early medieval France was impossible, given waves of newcomers. There are some lessons here for aspiring globalists.

The Anglo-Saxon tribes came first, beginning in Late Antiquity. These maps give a rough sense of the political divisions in England in 450, 525, and 600. The green patches represent the Saxons, Angles, and Jutes. Notice how quickly they go from small settlements to dominating the country.

The Anglo-Saxons formed their own shifting kingdoms, but faced further invasions, first from the Danish Vikings, then the Normans - Norse invaders who had settled Northern France.

The first two maps depict the Anglo-Saxon and Celtic kingdoms at the beginning and end of the ninth century. The Danelaw was the territory ruled by the Danish king. The map on the right shows the progress of the Norman conquest, beginning in 1066.

Certain things were needed for a nation to coalesce from this turbulent history. The first is time. After the Norman Conquest , England did not face another major threat for centuries. A degree of compatibility is also needed: Celts, Anglo-Saxons, and Normans all settled in the north and became Christian, although regional distinctions never truly disappeared. But just as importantly, England gradually developed structures that allowed its disparate population to develop organic national and regional cultures over the centuries.The English language was one of these, fusing French and Germanic roots into a powerful and unique tool of expression.

Prologue to the Knight's Tale, Ellesmere Chaucer, Huntington Library EL 26 C 9, f.10r., San Marino, CA

Chaucer's Canterbury Tales was an important early work in Middle English, the initial fusion of Anglo-Saxon Old English and Norman French. Begun in 1387, it is a collection of stories told by a group of pilgrims travelling to Canterbury Cathedral. The language took time to stabilize, with Shakespeare marking the beginning of Modern English around 1600.

Both the common language and common religious observances helped build a sense of national identity. This doesn't bode well for melting pot advocates.

The notion of the Rights of Englishmen was a key check on absolutism by enshrining certain personal liberties as inviolate and placing restrictions on monarchical power. The earliest of these would be the Magna Carta, which first appeared in 1215 and limited royal authority over church and nobility. Over time, additional limits were added, essentially developing the first concept of "human rights" without overthrowing the system or imposing an authoritarian central control. In fact, the Rights of Englishmen are the inverse of centralization, being rooted in the principle of freedom from tyranny.

Magna Carta (British Library Cotton MS Augustus II.106

While the Magna Carta has been somewhat mythologized over the centuries, it is a historically monumental political development. Independent nobility accommodate the development of organic regional cultures in a feudal system.

Note, however, the nationalistic nature of this formation. There is no claim to universality in something belonging specifically to "Englishmen." Even the Scots were only included after the Act of Union, though they were of little protection against the barbarous Enclosure Act. Although Imperial Great Britain was a different animal by then.

The Rights of Englishmen were protected by the Common Law, a legal system based on logic and the weight of precedent rather than a fixed law code or constitution.

Earliest known pictures of the English courts at Westminster Hall. Clockwise from top left: Common Pleas, King’s Bench, Exchequer, Chancery, circa 1460, Inner Temple Library, London

There is a flexibility built into the English legal approach, but it is predicated on shared values and homogeneous, high-trust local communities. Much of the Common Law depends on an understanding of unwritten cultural expectations and assumptions that took a long time to evolve, and are neither intuitive nor transferable to large non-English populations. The uniqueness of this is stark in comparison with the absolutist ideologies of monarchical or Enlightenment France.

Staying general, we can contrast the English notion of "rights" as the result of an inductive process, meaning developing organically from the bottom up, with the French idea of central control. Not surprisingly, the philosophical bent of the English Enlightenment is likewise different, tending towards practical, empirical ideals rather than absolutist rationalism.

So how is this expressed in the built environment?

Nonsuch Palace, detail from an early 17th century anonymous Flemish painting, oil on canvas, 151.8 x 302.5 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The greatest of Henry VIII's many constructions was built in the 1530's and pulled down in 1682. We can see from this picture that there is no sign of the Classicism that was well established in Italy. Instead, it combines medieval English traditions. Henry's daughter Elizabeth was a literary patron more than a builder, and was content to use her father's structures.

It was actually the growing strength of the monarchy that created the counter-pressure leading to the dismal fate of the Rights of Englishmen today. On the one hand, a popular Renaissance figure like Elizabeth I gave the country a common rallying point, but strong central power was contrary to the spirit of local, organic culture. This became starkly clear with the crowning of James I in 1603, when the king of a frequently hostile foreign neighbor was named king of England by bloodline.

Court society developed into a parallel culture to the ones they ruled over, one that was pan-European, rather than national in focus. That isn't to say that the king of France wasn't French, but that by the late Middle Ages, there is a marked consistency in court culture. The notion of noble birth created an unbridgable social chasm between aristocrats and commoners, while intermarriage bound the courts together more tightly, to the point that the king of Scotland could become king of England by ancestry.

Limbourg brothers, June and September from Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry f.6v., 1412-16; 1485-86, vellum, 22.5 x 13.6 cm, Condé Museum

A masterpiece of the Gothic court of the King of France's brother. Note the clear distinction between the laborers and the noble houses and the similarity between the courtly fantasy homes and Henry's Nonsuch.

The European courts were a proto-globalist structure, a disconnected and denationalized elite ruling people they view as almost a different species.This is critically important. The courts had much more in common culturally with each other than with their subjects, and strategic intermarriage gave them a cosmopolitan focus. They could leverage nationalism for their ends, but ultimately never could be OF the nation.The term "blue blood" originated as a reference to racial and familial purity in Muslim-occupied Spain, but evolved into a metaphor for the pallor that only could be attained by a life of complete luxury.

Edmund Leighton, To Arms! Sweet bridal hymn, that issuing through the porch is rudely challenged with the cry 'to arms', 1888, oil on canvas, 152.4 x: 105.4 cm, Private collection

Nobles presented themselves as bound by honor and duty...

William Hogarth, The Tavern Scene from A Rake's Progress, 1732-35, oil on canvas, 62.5 x 75 cm, Sir John Soane's Museum

... the reality, then as now, was considerably less charming

Hogarth's satirical series shows the fall of a young man who aspires to aristocratic debauchery before going broke and ending up insane.

James had the sense to rule with a modicum of prudence, but his son Charles was purely a creature of the insular world of the court, which he refashioned into a fantasy world of art, folklore, and watered-down Neoplatonism. Charles was more aesthete than intellectual, and his cultural projects were not a philosophically coherent program as much as a collection of personal whims that reflect positively on royal power.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I in Robes of State, 1636, oil on canvas, 248.0 x 153.6 cm, Queen's Ballroom, Windsor Castle

In some ways Charles resembles a better-read Justin Trudeau, the idiot scion of a former ruler who "leads" by symbolic gestures that indicate a general distaste for his national culture. In both cases, the unifying desire is to increase central control. For Justin, this is a weird blend of anti-Western collectivism, LGBT-envy, and Islamophilia, while for Charles, it was a blend of humanistic art collecting, romanticized chivalry, and an infatuation with the absolutist Catholic courts of Europe.

There isn't time to delve deeply into Charles' aesthetic "governance" but a few highlights will suffice to give some sense of the strange world of the Stuart court. He chafed against the traditional political restrictions on the English monarchy, desiring to take his place next to the absolutist Catholic monarchs of France and Spain. The problem is that he lacked leadership ability, and his ham-fisted ways to maneuver around Parliament combined with his favorable position towards Catholicism and its culture to trigger the Civil War. What is notable is how the desire to increase royal power moved in lockstep with the alien internationalist culture of the European courts.

Simon Pass, engraved frontispiece to The Workes of the Most High and Mightie Prince, James, 1st ed., London: Robert Barker and John Bill, 1616

The ideological rift with Charles and England began with his father, King James VI of Scotland, who was next in line when Elizabeth died without issue, and was crowned James I of England in 1603. Unlike his son, James was literary minded and the author portrait to his collected works emphasized his insignia of royal power. The Scottish parliamentary tradition was much weaker, and James chafed under the restrictions on his English powers. He governed competently enough that tensions didn't escalate dangerously, but Charles was steeped in the same alien authoritarian perspective, and lacking his father's acumen, allowed the the situation to worsen until war broke out.

Charles' character was shaped by certain members of his father's court. George Villiers, first Duke of Buckingham, was a James' handsome royal favorite and likely lover and a tremendous art patron who effected a dashing knightly image. Charles' constant circumvention of Parliament's attempts to limit his Lord Admiral and foreign minister's disastrous policies and personal extravagance helped inflame the conflict.

Peter Paul Rubens, Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Buckingham, 1625, oil on panel, 46.6 x 51.7 cm, Kimbell Art Museum, Dallas

In this draft for a grand portrait, Rubens, the favorite artist of Charles and his circle, captures Buckingham's grandiose persona. The portrait was never finished, since the corrupt and incompetent Buckingham was assassinated by disgruntled army officers in 1628.

Daniël Mijtens, Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel and Surrey, oil on canvas, 207 x 127 cm, National Portrait Gallery, London

Arundel (1586-1646) came from a noble Catholic family that had fallen from favor during Elizabeth's reign, but were restored by James. The Earl himself formally converted to his ancestral religion after leaving England for good in 1642. In this portrait, he is showing his extensive collection of antique sculpture, which is set in a classical hall. Arundel's embrace of the humanistic art theory and aesthetics was irresistible to Charles and Buckingham.

Charles' embrace of alien cultural values and acceptance of a hostile religion drove a wedge between him and Parliament.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I and his wife Henrietta Maria with their eldest children: Charles, Prince of Wales (Charles II) next to his father and Mary, the Princess Royal, in the arms of her mother, 1633, oil on canvas, 303.8 x 256.5 cm, Royal Collection

Marrying Henrietta Maria (1609-69), a French princess, and setting up a private Catholic court for her didn't help matters. The queen was widely disliked for her blatant Catholicism and her profligate spending.

Charles set out to build one of Europe's great art collections, competing against the King of Spain above all. Elite collecting was a sign of taste as well as wealth, and was based in an aristocratic offshoot of the humanist art theory of the Renaissance. Classical sculpture and Renaissance painting were most prized, but contemporary artists developed dramatic courtly styles based on Italianate models to meet this demand. No one was more successful at this than Rubens, a painter and surprisingly skilled diplomat whose career brought him multiple titles, enormous wealth, and the friendship of kings.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Apotheosis of James I, 1632-34, oil on canvas on wood support, 975 x 625, Main Banqueting Hall, Banqueting House

Charles had Rubens paint this tribute to James in an ornate Venetian-style ceiling as a tribute to his dynastic aspirations. The irony is that he was executed outside the same Banqueting House.

Charles could never convince Rubens to move to England, but he got an solid consolation prize when Anthony van Dyck, Ruben's greatest pupil and equal in technical ability, if not inventiveness, agreed to become his court painter. One of history's great portraitists, van Dyck gave Charles an artist that could hold his own with Philip IV of Spain's Diego Velazquez, or the popes' Gianlorenzo Bernini, while giving the Stuart court a romantic, dreamy, luxurious appearance.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I with M. de St-Antoine, 1633, oil on canvas, 370 x 270 cm, Royal Collection

Charles LARPing as a knight with his French riding master. Even his equestrian style was un-English.

Anthony van Dyck, The Five Eldest Children of Charles I (Princess Mary, of William and Mary fame, is on the left), 1637, oil on canvas, 163.2 x 198.8 cm, Royal Collection

Anthony van Dyck, Lucy, Countess of Carlisle, 1637, oil on canvas, Private collection

His fluid style gave the court a rich, luxurious look that was very popular. The settings are Italianate rather than English, reflecting the internationalist aristocratic taste.

Anthony van Dyck, study for The Five Eldest Children of Charles I, 1637, oil on canvas

The realism.

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Inigo Jones, before 1641, oil on canvas, 64.1 x 53.3 cm, National Portrait Gallery

Anthony van Dyck, Sir Kenelm Digby, circa 1640, oil on canvas, 117.2 x 91.7 cm, National Portrait Gallery

Anthony van Dyck, Self-portrait with a Sunflower, after 1633, oil on canvas, 58.4 x 73 cm, Private collection

Key figures in court culture: architect Jones, philosopher and historian Digby, and van Dyck himself.

It was into this context that Inigo Jones (1573-1652) introduced Palladian architecture and a form of participatory drama called the masque, with costumes, stage machines, and mythological symbolism derived from Italian models. The most ambitious of Jones' plans for Charles was a huge Palladian palace to replace Whitehall and rival the Escorial, the massive palace/church/school/library complex built by Philip II of Spain. Charles lacked the financial resources of the Spanish monarchy, which meant the palace was unlikely even before the Civil War buried the dream for good, but it speaks of an aspiration to continental models of authoritarian architecture. Jones' Banqueting House is all that survives.

Inigo Jones, plan for the Palace of Whitehall, 1638, from William Kent's The designs of Inigo Jones..., London: Benjamin White, 1770.

Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juan de Herrera, El Escorial, 1563-84, near Madrid

Pedro and Luis Machuca, Palace of Charles V, 1527-68, Grenada

Kent was a close associate of the Earl of Burlington, and a key figure in the revival of English Palladianism. For a digital of the edition, click here. For the original 1727 edition, click here.

Inigo Jones, Banqueting House at Whitehall, 1619-22, London

The Banqueting House was the one piece of the palace that was built, and it was the symbolic center of Charles' fantasy world. It is a pure application of Palladian ideals, both in its style and in the perfect double cube geometry of its proportions.

There is a reason that this was the site of his execution. Symbols have power.

The simple classical interior contrasts with Ruben's grand ceiling.

It was here that Jones staged his masques, a kind of costumed symbolic drama that became popular in the European courts in the late sixteenth century. The English masque began in the Elizabethan period, but reached its peak under James with Ben Jonson writing the scripts and Jones designing the sets. After Charles came to power, Jones took over, enhancing the visual experience over the text.

Design for the climax of Coelum Britannicum, 1634

Costume design for a Star from Oberon the Faery Prince, 1610

Costume study for the role of Chloris played by Queen Henrietta Maria, for Chloridia, Ben Jonson's last masque, in 1631

Stuart's masques tended to follow a pattern, where troubled times are restored to harmony by the virtue of the royal couple. This is the humanist Golden Age seasoned with the Elizabethan use of the the myth of Astrea, and converted to royal propaganda. Only the masques were private.

It is unclear whether Charles believed in the Neoplatonic occultist interpretation of architectural geometry, though some in his court did. What is clear is that while he retreated into his imaginary world, England was sinking into chaos.

Gerrit van Honthorst, Apollo and Diana, 1628, oil on canvas, 357.0 x 640.0 cm, Queen's Staircase, Hampton Court Palace

This painting captures the spirit of the masque, with Buckingham and his wife Catherine Manners before Charles and Henrietta Maria dressed as the gods of the sun and moon. The harmony brought by these light bringers is reinforced by the figures of chaos being driven into the darkness below them.

The religious dimension of the Civil War was also exacerbated by Charles' centralizing impulse. England had been split between Catholics and Protestants since Henry VIII declared the Church of England independent of the pope, but the Protestants were themselves divided between high church Anglicans and largely Calvinist Puritans. Elizabeth and James ruled with an informal common law type compromise, and didn't apply too heavy a hand to religious matters. Charles changed this by appointing William Laud Archbishop of Canterbury, who imposed an almost Catholic vision of hierarchy and aesthetics on the English church. This was intolerable to the Puritans, who saw the emphasis on art and beauty as decadent, and Laud's enforced uniformity as persecution.

Two takes on Laud: in the court style of van Dyck, and in a satirical polemic:

After Anthony van Dyck, William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, oil on canvas, 123.2 x 94 cm, National Portrait Gallery

Cartoon showing the devil offering Laud a cardinal's hat from a Puritan publication called A Prophecie of the Life, Reigne, and Death of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1644

This cartoon suggests that there was a more sinister cast to Stuart spirituality as well, at least in the eyes of its English critics. Laud is shown as a demonic being himself, but he is distinguished from the devil that represents the evil forces he serves. Instead he appears with antlers, like the ancient Celtic type of primordial pagan Horned God, a common figure in black magic rituals. This can be read as a harshly critical reference to Laud's interest in the esoteric, occult symbolism of Charles' court culture.

The Occult and the International Elite

English occultism, like English empiricism, emerged from the new optimism in human learning unleashed by the Renaissance. The beloved ancient texts of the humanists were filled with esoteric and occult ideas that bubbled up from late antiquity and fueled the syncretism of Renaissance thought. Hermetic and Neoplatonic ideas mixed with Kabbalistic numerology and the supposed sayings of ancient sages like Zoroaster and Orpheus. The Band mentioned Marsilio Ficino in an earlier post as someone who tried to synthesize some of this knowledge with Christianity, but there were others, like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Paracelsus who appear to have seen Christianity as just one source of ancient knowledge. The same impulse that drove Francis Bacon’s scientific method was also behind the search knowledge of esoterica.

English occultism, like English empiricism, emerged from the new optimism in human learning unleashed by the Renaissance. The beloved ancient texts of the humanists were filled with esoteric and occult ideas that bubbled up from late antiquity and fueled the syncretism of Renaissance thought. Hermetic and Neoplatonic ideas mixed with Kabbalistic numerology and the supposed sayings of ancient sages like Zoroaster and Orpheus. The Band mentioned Marsilio Ficino in an earlier post as someone who tried to synthesize some of this knowledge with Christianity, but there were others, like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Paracelsus who appear to have seen Christianity as just one source of ancient knowledge. The same impulse that drove Francis Bacon’s scientific method was also behind the search knowledge of esoterica.

An Ape as an Allegory of Art, title page of Robert Fludd's De naturae simia seu technica macrocosmi historia, Johannis Theodori de Bry, 1624

Fludd was a leading figure in seventeenth-century esoterica. This image depicts the connections between things that make occult knowledge and power possible. The ape in the circle is an old metaphor for artistic expression as the imitator, or "ape" of nature. The circle represents types of representation: geometry, mathematics, astrology, optics, art, architecture, and music, all of which were believed to share mathematical foundations. The idea is to understand this deeper foundation behind surface appearance, and math has an internal truth value that is attractive.

It is noteworthy that this power-seeker - and occultism is nothing more the naked pursuit of power – pressed an imperialist policy as a royal advisor, and may have coined the term “British Empire”.

Bacon knew the older Dee, though the extent of the latter’s influence is uncertain. He had Neoplatonic leanings but did not promote specifically Rosicrucian ideas although James I, who had written a book on demonology, was less favorably disposed to the occult than Elizabeth. But major figures in Charles’ circle, including the queen, Laud, Van Dyck, Jones, poets Ben Jonson and John Donne, and philosopher Kenelm Digby, were given to esoteric thought to some degree, and court culture, especially the masque, was filled with hermetic and alchemical imagery.

Excursus

The idea of an alternative history brings us back around to historiography again (if you are interested in this topic, click here, here, and here for three connected posts on historiography). The easiest way to keep these terms straight is this: if history is the story of what happened, historiography is how that story is told. But on either level, we are talking about a story, meaning a structured narrative put together by someone.

A conventional story represents a series of connected events unfolding in time, which corresponds to our perception of time as a continual forward progression. The difference is that the story is a human creation where events gain significance by their position in the authorial structure.

The human experience of time is also sequential, but the specific occurrences are random. Tropes like Chekov's gun are meaningful because they are singled out in a narrative construct; in real life, we continually encounter things that never impact us in any way. At the same time, we have known since Aristotle that causality exists, and events that do not affect us personality have consequences.

Temporality, or the nature of time, was a major trend in twentieth-century thought, both quantitatively and qualitatively, in physics and philosophy respectively. To oversimplify, the overarching conclusion is that time is experienced subjectively, either as the temporal nature of the gerund in "Being" or in relation to movement and location in physics.

Jumping concepts: if history is a structured temporal sequence of causally-linked events, and temporality is a subjective experience, then history is a structured, subjective projection. And if we organize our subjective, temporal experience through narrative, then this projection, this representation of the passing of time necessarily takes the form of a story.

As the subjective representation of temporality, history must take narrative form.

Philippe de Champaigne, Saint Augustine, circa 1645 to 1650, oil on canvas, 78.7 x 62.2 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Looking back, we can see an early discussion of the personal nature of time in the work of St. Augustine, who presented past, present, and future as three separate moving states in his Confessions. This may not seem particularly profound to modern readers on the surface, but tracing ideas is a valuable way to uncover the presuppositions and connotations in their formation. This is important because Postmodernists frequently use established concepts in dishonest ways in order to give their lies the illusion of credibility. By understanding why the concept was credible in the first place makes it easy to identify where the deception is occurring.

Augustine's ontology - his concept of ultimate reality - is Christian, which means his notion of history is eschatological, or tied up with God's larger plan. Time is meaningful from this perspective, because it unfolds a divine narrative. Human experience may seem random, but that is because human perception is so limited. And each individual can have a meaningful personal history despite the apparent chaos around them by following the path to salvation. Your story unfolds within God's story, which provides the purposefulness, or narrative plot, to the passage of time. This becomes... 'problematic' from a materialist perspective. Something to puzzle:

A Postmodernist might argue that there is no "history", only subjective narratives, one as good as the other. But we know Postmodernists to be hopelessly limited by binary thinking even when they aren't trying to lie, and seemingly incapable of conceptualizing shades of gray. To a realist, the limitations of human communication are self-evident, and historical narrative simply an imperfect way of representing events that are of significance to us. So we are back into the realm of subjectivity.

Tanni Koens, Is Ego Just An Empty Shell, uploaded November 24th, 2010.

So many historians incoherently seek the ur-plot, the definitive story of some event, while denying the providential framework needed to give purpose to history. There is no devinitive story; just one chain of an endless web of butterfly effects singled out by a historian. The narrative form lurches along, but the soul that gave it meaning is gone.

In this way it resembles the Postmodern, secular West, which seems to think it can enjoy the fruits of a Christian society without Christianity.

Thomas Couture, The Romans of the Decadence, 1847, oil on canvas, 472 x 772 cm, Musée d'Orsay

So narrative authority is reduced to nothing more than the author, which means that history, on at least one level, is just another attempt by humans to impose their desired meaning on the world. But this is too simplistic on its own. "History" is also a discourse, with a self-defining community, institutional gatekeepers, and historiographic expectations. Historians are constrained in ways that fiction writers are not; not because they tell true stories, but because they follow a discursive framework that determines what is acceptable. In this case, it is not sufficient just to remove divine teleology; a new idol was needed to provide narrative direction and meaning.

Disney's Carousel of Progress

If history is to be meaningful as a narrative, it requires some sort of meta-framework, or larger structure to direct the plot. For Augustine it was God, while for moderns, it was:

Progress

Progress was a great concept, because it had that illusory Hegelian transcendence AND glorified human cleverness. It inverts the Renaissance cult of the ancients by making the present day the best and allowing "thought leaders" to dismiss the accumulated wisdom of our ancestors as "backwards". The cult of progress meant the Enlightenment was a priori good because it moved away from cultural and religious traditions and towards the top-down theoretical fakery that passes for erudite conversation in Postmodern circles. But this is a man-made narrative without a transcendent pole star.

Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996, acrylic, oil, polyester resin, paper collage, glitter, map pins and elephant dung on canvas, 253.4 × 182.2 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

It is true that progress has applied to technology, which follows developmental chains by nature. But as we survey the dyscivic contemporary landscape and contemplate declining IQs, it is hard to see the appeal of cultural "progress" beyond vanity.

Ofili's bloated figure is festooned in elephant dung and pornographic cutouts for various reasons that don't detract from the primary goal of insulting Christianity. Of course the cuckservatives play their part and cluck disapprovingly about imagined future consequences.

So edgy...

The excursus ends with a question: if the

notion of progress in human nature

is a myth, why cling to it?

Alt-History

If narratives are necessary for humans to make sense of historical events, but the idea of materialist metaphysical progress a pernicious fantasy, what about a story that better hews to reality? Consider the disconnect between the elites in Charles' court, and the complicated set of traditions that comprised the English people at the time. He was a champion of a foreign culture who was friendly to a hostile religion and pursued an alien policy of royal absolutism. Add the air of occultism and masked revels and the outbreak of Civil War looks a bit different than the usual historical narrative of religious zealotry.

Robert Walker, Oliver Cromwell, circa 1649, oil on canvas, 125.7 x 101.6 cm, National Portrait Gallery

Not to say that Cromwell was a "good guy", since he quickly assumed dictatorial power, but just that it is not hard to see how cultural optics around the Stuart court could enrage the populace, if we take a different perspective.

The Restoration in 1660 brought Charles' son Charles II home from France and onto the throne, but there would be no revival of the fantastical culture of his Father's court.

John Michael Wright, Charles II of England in Coronation Robes, circa 1661-62, 281.9 cm x 239.2 cm, Royal Collection, Hampton Court Palace

Charles II had been raised by his mother in exile in the French court, and did not share his father's love for art collecting or esoterica. Although his Catholic sympathies (he converted to Catholicism on his deathbed) created some issues, the "Merrie Monarch" was immensely popular with the English people

Jan Griffier I, The Great Fire of London, 1666, oil on canvas, 103.1 x 165 cm, Museum of London

The catastrophic fire of 1666 made architecture a sudden concern for Charles, and brought Christopher Wren into the limelight. Wren's St. Paul's was only the most spectacular of the many churches he designed in for the rebuilding.

John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor, Blenheim Palace, 1705-22, Oxfordshire, England

Wren's prominence and Charles' French background are indicators of a brief English interest in a more continental "Baroque" form of Classical architecture.

Blenheim, the ancestral home of the Churchills, has the curving facade, dramatic shadows, and forcefully projecting forms that we see in the tamer examples of the Italian Baroque. As you approach the main entrance, note how the French-style porch seems to push out towards you. This sort of interactive grandiosity is very different from the simple geometric harmony of Jones' Palladianism.

From this angle, we get another glimpse of what an alternative history might look like. Architectural historians trace the move from Palladian Classicism to a more Baroque classicism as a shift within the larger flow of the stylistic timeline. This is factually true, but is is descriptive, and offers little insight into the structural significance of such a change. Through the lens of the nationalist/ globalist framework, we notice that both styles were completely foreign to English traditions and accompanied a king who embraced an alien, pan-national culture.

Architecture IS your formative environment. The symbolism is habituated on the deepest level possible, given your psychological make up. The largest, grandest structures don't just express social authority in instantly recognizable terms, they give that authority a concrete form. The word façade meant face or front; official architecture tells you what authority looks like. To reiterate the lesson for Postmodernism:

Stuarts redux didn't last, and in 1688, Charles' brother James was overthrown by William of Orange, who was married to his daughter, Mary of England in the Glorious Revolution.

A Perspective of Westminster abby from the High Altar to the West end Shewing the manner of His Majesties Crowning, in Francis Sandford, The history of the coronation of ... James II ... and of his royal consort Queen Mary: solemnized in the Collegiate church of St. Peter in the city of Westminster... London, T. Newcomb, 1687

With the coronation of the staunchly Protestant William, the religious confusion that had hung over the monarchy for over a century vanished with the continental Baroque.

Which brings us back to empiricism and the architecture of the English Enlightenment. The eighteenth-century brought about burst of English achievement and "progress", but planted more seeds for our Postmodern cultural wasteland.

No comments:

Post a Comment