If you are new to the Band, please see this post for an introduction

and overview of the point of this blog

and overview of the point of this blog

A wrap-up of a month of epistemology and historiography and a walk down some unusual paths:

Reviewing the Postmodern landscape we see a recurring pattern of hypocrisy and deception. Discourse is used to state with certainty that there is no certainty in discourse. We are told that fixing discursive meaning is an act of oppression while moral meaning is assigned to discursive categories. They inform us that historical periods are self-serving constructs, then establish self-serving historical periods with Postmodernism conveniently located as the climax. Apparently they love Science! while ignoring objective facts for false narratives. This raises the question as to whether it's fair to call Postmodernism Satanic.

Gustave Doré, Satan Flies to Earth, 1866, engraving from John Milton's Paradise Lost, Book 3, 739-41 "Toward the coast of earth beneath, Down from the ecliptick, sped with hoped success, Throws his steep flight in many an aery wheel."

This is a deceptively tricky question, especially from an empirical perspective like the Band's. The simple answer would be to ask a Christian, but different denominations have different interpretations of what Satan is. What about "Satanists"? Their official "church" denies metaphysical reality altogether and claims he's just a symbol of self-empowerment (the Band is not interested in linking to that lot). They're likely lying, and their website is unhelpful

Historians describe Satan as an evolving concept with roots in antiquity, but their findings are riddled with Postmodern biases and hypocrisies. They seem largely driven by an anti-Christian spirit that seeks to use history to "debunk" articles of Christian faith as "not Biblical", as if their ideological misconception of Christian epistemology was somehow meaningful. An empiricist cannot comment on the truth of faith claims, but can observe how these claims manifest in the real world. They can be evaluated on the basis of the behavioral and civilizational outcomes that they support. Both the theory and practice of Christian interpretation show nothing strange about an evolving expression having theological weight. The contentious history of the Eucharist or Host, the communion wafer consumed in many Christian services is a fine example.

Nicolas Poussin, The Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, 1647, oil on canvas, 117 x 178 cm, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

Poussin captures the origin of the Eucharist in an interpretation of the Last Supper. The connection between the Host and Christ's body is made by Christ's gesture.

Hours of Mary of Burgundy, Bleeding Host of Dijon, ca. 1470s parchment, Vienna, National Library, Ms. 1857, folio 2v

Medieval theologians interpreted the line "Eat of my Flesh" literally, claiming that the Host was mystically transformed into the actual body and blood of Christ. This image represents one of many miraculous Hosts that revealed their nature in a supernatural way. This one was reported to have bled, but the artist interprets the wafer with an image of Christ to show the reality of the presence.

Lucas Cranach the Younger, The Last Supper, 1565, oil on panel, Schlosskirche, Dessau

To the Protestants, the Host was merely a symbolic communion without a metaphysical component. In a rare example of a Protestant alterpiece, we see prominent Reformers in the guise of Apostles signifying this fellowship.

So we have a difference in scriptural interpretation, but neither position questions the core tenets of Christianity; namely the theology of the Incarnation and Redemption.

Interpretation is an integral part of any text-based religion, both to apply the text to unforeseen circumstances and to bridge the gap in time and place between the reader and the source. The Bible is especially transparent in acknowledging that while it is the word of God, the fullness of its truth is beyond limited human minds. This is the point of St. Paul's famous metaphor of seeing through a glass darkly. Given this situation of ultimate reality imperfectly signified, understanding is necessarily marked by disputes, evolutions, and shifts over time. The condition is that they remain consistent with the scriptural source. The historical development of Satan is this sort of process.

Modern scholars go astray when they claim to reject purportedly unproven Christian assumptions for "facts", but replace the existing interpretation with unproven assumptions of their own that conform less closely to empirical reality. Three overlapping areas of academic "reinterpretation" of Christian belief can be identified for the sake of discussion, though these are my categories and are not definitive:

All of these share claims of objectivity, but are riddled with disciplinary blindness, unacknowledged presumptions, and category errors. The seek to subvert textual authority and Christian interpretation to their own methodological or purely solipsistic projections.

Literary criticism refers to a loose grouping of attempts to apply techniques of literary analysis to the Bible. It is true that the authorship of the Bible is a historical jumble, with the Old Testament coalescing over the first millennium BC and New over the first few centuries of the Christian era. Literary criticism comes closest to history when trying to untangle distinct voices from within this web.

Harold Bloom used close stylistic analysis to try and separate the work of the of one author of exceptional originality that he called the "Yahwist" from the rest of the Old Testament. His rationale was mapped out in his earlier Anxiety of Influence, where he defined literature as a chain of influence and creative conflict over time. Bloom is an insightful reader, but his vision is purely literary and unfolds within the conceptual silo of a 20th century English department. He is not wrong so much as limited, and here he attempts to account for the extraordinary power of the Bible by clearing a space at the table for its strongest voice.

The Jesus Seminar was a multi-decade effort to parse the Bible to get at the "historical" Jesus. It resembles the methods of the Renaissance humanists who recreated proof texts of classical authors by comparing later redactions. The approach is epistemologically suspect for obvious reasons, and seems primarily focused on providing ammunition to reimagine Christ as a New Agey sage than signifier of transcendence.

Ranking Bible authors misses the painstaking process of assembling the unified text in late antiquity, while treating the Gospels as redactions of a lost ur-text misunderstands the point of the Bible as an imperfect signifier of ultimate reality. By imposing unexamined truth claims over the finished text, the critic literally elevates themselves to God's place.

Pompeo Batoni, The Ecstasy of St. Catherine of Siena, 1743, oil on canvas, Museo di Villa Guinigi, Lucca

St. Catherine of Siena, one of the great mystics and theologians of the Western Tradition can be reimagined as a teenager with an eating disorder. Of course, this recasts Christian devotion as mental illness. Curiously, there is little interest in a similar project focused on the Buddha or Mohammed.

If identifying individual voices is one literary critical error, overemphasizing the fragmented nature of Bible authorship is another. The absence of definitive writers lends itself to the application of Foucault's "author function" and its descendants, turning the test into a mere projection of an episteme. This theoretical historiography moves us into the other categories.

Social science approaches view the Bible as a set of cultural motifs and expressions rather than exclusively literary influences, but given the overlap between these domains, the two closely relate. The myriad tiresome attempts, from Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung to Jordan Peterson, to "explain" scriptural passages as universal archetypes belong here. Numerous ancient figures have been offered up as the "source" for Jesus, presumably as a way to discredit Christianity by "exposing" its central mystery as nothing more than a historical distortion of myth. The fact that all the prototypes were all conceived in completely different terms metaphysically is only relevant if you understand Christian metaphysics.

Osiris, c. 1280 BC, Tomb of Sennedjem , Luxor, Egypt

Mithras Petra Genetrix (born from the rock), 180-192, marble, Epigraphical Museum, Baths of Diocletian, Rome

Dionysios, c. 440-430 BC, Attic Red Figure Kylix, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge

The Egyptian Osiris and Greek Dionysios were both resurrected gods. Mithras was a Persian sun god popular in ancient Rome with especially dishonest arguments linking him to Christ.

Notice how flawed these archetypes are. None capture the central Christian mystery of collective redemption through God's own sacrifice, nor position themselves as the ontological fulcrum between objective and ultimate reality. If these archetypes reveal anything, it is the uniqueness of Christ and Christian metaphysics in general. The underlying error is in treating the notion of "collective unconscious" as objective reality that accounts for the human desire for transcendence. From an empirical scientific perspective, these ideas are gobbledygook. Collective unconscious doesn't exist in a verifiable way, and is best thought of as a limited metaphor for common traits, much like Freud's unconscious. Misusing a post-facto abstract figuration as an "explanation" of the phenomenon that the abstraction is based on is a common Postmodern trick and is literally tautological. It's also idolatrous.

Esteban March, The Golden Calf, mid-17th century, oil on canvas, 90 x 114 cm, Fundación Banco Santander

Peddlers of false archetypes offer images of their own projection as meaningful truth on nothing but faith in their own perspicacity, but hide this snake oil behind a figleaf of cultural wisdom. In professing to answer a need for transcendence, they create a false god in their own image. This painting contrasts the worship of a human creation with the revelation of real transcendence in the background.

So, as was the case with literary approaches, we have the critic usurping explanatory power - God's creative energy - from the Bible for their own aggrandizement. Coincidence?

Historical approaches bring us back to the question of origins by attempting to untangle the complex history around the development of the Bible and early Church. It is open to literary and social science "insights" but works to ground and analyse the evolution of Christianity within the larger historical context. This seems fine on the surface - empirical historiography is an endless refining of our understanding of the past - but there's a consistent perspective in these studies that reveals another agenda.

This book is a fine example of the way these approaches overlap that relates to the topic of this post. It traces the history of Satan to prove the thesis that the Christian concept of the Devil is based on tradition that has "displaced scripture" and "disguised itself as scripture." He declares that Satan's character deteriorated over time "simplly as the natural result of unfavorable media attention", but has the temerity to declare his conclusions important to all "people of the Book" who believe the Bible to be the "inspired word of God."

What this Distinguished Emeritus Professor of English is doing is typical of historical approaches to the Bible. He declares on his own authority, that his siloed ignorance of Christian epistemology takes precedence over the Christian tradition of interpretation and exegesis made necessary by the nature of the darkling glass. The way that he cherry picks other sources from ancient Near Eastern texts to "corroborate" his misreading is also typical. Ironically, another pattern of Satanic usurpation of authority.

The hypocracy and unacknowledged bias in historians' efforts to set the Christian record straight becomes obvious when you realize that the historical origins of other religions do not receive the same treatment. Let's consider some examples:

Hinduism

The roots of this religion are ancient and shrouded in historical fog. Sources date back to the Vedic period (second millennium BC) and likely originate in the earlier Indo-Aryan migration era. But the classical Hinduism that evolved over centuries is quite different from the ancient Vedic religion.

Lord Rudra, fifth to seventh centuries, Elephanta Caves, Mumbai Harbor, India

Shiva Nataraja (Lord of Dance) from Tamil Nadu, India, circa 950-1000, Chola Dynasty, copper alloy, 76.2 × 57.1 × 17.7 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Rudra was an ancient Vedic deity with singular and multiple identities who became conflated with aspects of Shiva in ways that are not historically clear as Hinduism evolved. Curiously, historians don't feel obligated to "demonstrate" the inauthenticity of modern Hindu beliefs

.

Buddhism and Jainism

These contemplative religions appeared around the same time (5th century BC) and with spiritual leaders so similar, they seem almost the same in representations. Both the Buddha and Mahavira promoted the belief that the world was a cyclical illusion, and the goal of the soul was to escape to transcendence through enlightenment.

Buddha Seated on a Lion Throne, 600-730, Cave 2, Ellora, India

Mahavira, early ninth century, Cave 32, Ellora, India

There are distinguishing differences between these two, but the overall similarity reflects the common conception of the two enlightened sages. Strangely, historians don't question the historical existence of the two, argue they were the same guy, accuse one of stealing from the other, or claim they were archetypes of Pythagoras or Osiris.

Judaism

The origins of Judaism are also historically complex. The Torah was authored over the first millennium BC, and as the core of the Old Testament, is the aspect most familiar to Christians. This religion was overhauled between the second and fifth centuries AD, with the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds, or collections of traditions and rabbinical wisdom. This is obviously a very different authority than the prophets.

Marc Chagall, Moses Receives the Tablets of Law, 1966, oil on canvas, 237 x 233 cm, Musée Marc Chagall, Nice

J. Scheich, Talmud Study, circa 1900, oil on canvas, 58 x 79 cm, Private collection

Visual interpretations of authority. Chagall captures the contrast between the transcendent source of the Law and the human experiences of the waiting crowd or prayerful rabbi. Note how Chagall uses color to distinguish the earthly Moses from the golden divine light.

The human aspect of Talmudic authority is evident in contrast. The adoption of later, extra-Biblical, "cultural" interpretation is no different from Christian practice, yet there are strangely few (meaning no) historians claiming listening to a rabbi in synagogue rather than watching a priest sacrifice in a temple as an opportunity to lecture modern Jews on the authenticity of their faith. Religions are social organizations. They evolve.

So it is exclusively targeted at Christians

Must just be a coincidence. Nothing to see here. Move along.

One common historical "method" is to treat the Bible as a collection of poorly assembled historical documents to be clarified and corroborated by other ancient sources. At this point, it comes closes to projects like the Jesus Seminar, which were classified as literary for the sake of convenience (Postmodernists are not especially insightful in noticing that categories are always a compromise). Manuscript finds like the Nag Hammadi trove and the Dead Sea Scrolls take center stage for their alternative perspectives on the historicity of the Bible.

Nag Hammadi codices in 1945

The history of the early Church is fascinating and the theology took time to develop. But seeking to "explain" the Bible by evoking sources that were not included during the process of sorting out the finished version fundamentally misses the point of scripture as an expression of Christian dogma.

Elaine Pagels is a Christian apostate and darling of academic Bible historians with enough globalist acolades to make a tinpot dictator blush, including Rockefeller, Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundation Fellowships and a National Humanities Medal from Obama's White House. I'll just leave the following quote from Britannica here: "[while] Pagels’s interpretations were sharply criticized by traditionalists, who felt her claims were not supported by the texts and who objected to her feminist interpretation of scripture, they were well received by laypeople who were disaffected with mainstream Christianity." In short, she made her reputation by studying the textual history of the early Christian period, and mastered the art of muddying the waters around the canonical Bible and contemporary writings excluded from it.

Pagels' Gnostic Gospels largely reintroduced Gnosticism to serious study in the West. It also initiated a deliberately deceptive process of referring to these heretical texts as "gospels".

While it is true that gospel simply meant good news, there's a reason why that word is used rather than testimonial or some other synonym.

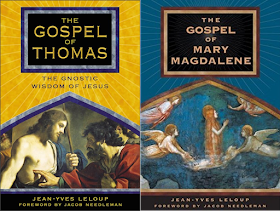

Works like The Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Mary Magdalene are titled to suggest comparable significance to Biblical books. This is dishonest; the Bible was edited to reflect the closest consensus Christian interpretation possible of ultimate reality. These were't. Excluded writings have nothing to say about Christian epistemology because, in those terms, they are by definition not Gospels. What could be the value in attributing heresy to Jesus?

The Gospel of Judas actually manages to invert Christian morality. Our friend even turns up to provide commentary on the foundational importance of this text to Christianity.

This paper by Pagels shows her method of reducing the Bible to a narrow historical literalism that it doesn't claim, then using that as a standard to criticize Christians for failing to live up to their own holy book. She is Postmodern in her sloppy reasoning, hermeneutic ignorance, and faith in false assumptions; for example, the endemic canard in Postmodern historiography that Christian European identity was formed in negative opposition to immoral stereotypes rather than as an expression of shared values or culture. The subtitle of one of Pagel's gems: The Origin of Satan: How Christians Demonized Jews, Pagans, and Heretics, pretty much sums it up.

Ecclessia and Synagoga from Strasbourg Cathedral, circa 1230, Musée de l'Oeuvre Notre-Dame, Strasbourg

These allegorical pairings were not uncommon in the Middle Ages, and contrasted the enlightened vision of Christianity with the blind adherence to the old Law in Judaism. The similarity and differences between the figures signify the common origins and the Gospels' superseding of the Old Testament.

Works like this help us understand historical ideas, but they are exactly the sort of image that Postmodern "historians" will cherry-pick as evidence of the negative process of Christian identity formation. It is odd that no other group identities are subjected to the same scrutiny.

Several lies compound in this notion of negative identity. Poststructuralist linguistics and deconstruction contribute the idea that meaning (understood as an operation in a language system) expresses only difference and has no positive significance. Lacanian psychology "proves" that our personal identities are also formed oppositionally, first in our self-awareness of our seperation from the world (the Mirror Stage) and then socially, in the gazes of others. Foucauldian morality lurks in the shadows, with history a branch of discourse, discourse serving power, and power being oppression. Together, they cast they cast the Christian European nations as ciphers that exist only in opposition to a false discursive image of those they oppress. Sound familiar?

Since historical identity is merely a marker of false difference, what the historian must do is identify the stereotyping, or, in preferred Postmodern parlance, the "othering", against which it creates itself. The notion of the Other is a magic talisman throughout Postmodern thought. It is used to shrilly dismiss any empirical difference as oppressive stereotyping.

More othering. Note the "Special Thematic Strand" at the bottom. "Interdisciplinary" also makes an appearance. I can't make this up.

Replacing Christian metaphysics with empirical lies is not a forward move. And this false concept of negative identity is a lie. All identifiers are relational. All definitions imply difference. This does not prevent them from connoting through analogy AS WELL. The inability of practitioners of deconstructive "logic" to understand the meaning of "both at once" resembles a learning disability. Overall, a pattern emerges where ignorance and hypocrisy support an illegitimate authority that is then used for propaganda and grievance slinging. They want to keep significance of the Bible as holy scripture to Christians, but override Christian tradition in interpreting that text. There is a deep misunderstanding of Christian epistemology combined with an unfounded faith in their own blinkered and leftist-converged methodologies. The problem is that you have to be capable of holding two thoughts at once:

The Bible is literally true as God's word

The Bible is a dark glass, and the truth is unclear without Christ

Revisiting our epistemology diagram from an earlier post, we are reminded of some basic facts. Ultimate reality lies beyond the scope of empirical knowledge and claims about it, whether admittedly or not, are faith claims.

In Christian terms, God is ultimate reality and humans are flawed and finite. Where do they meet?

The hermeneutic problem, or the need for interpretation is present from the outset, and it won't be resolved with a breezy quotation from Babylonian myth or the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Christian has to know God and can't "know" God, meaning some sort of accommodation essential. The notion of a history professor fixing "original" Christian meanings was always ridiculous.

The Limits of Empirical Knowledge

The Fall is an aspect of Christian ontology that is different from the various utopianisms that have plagued humanity because it holds up from a strictly empirical perspective as an accurate representation of human nature. It is easiest to explain through the parallel visualizations of pictures,and philosophical analogies from the previous post.

Johann Wenzel Peter, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, between 1800 and 1829, oil on canvas, 336 × 247 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana

Victor Pillement and Joseph Théodore Richomme, Adam and Eve standing on each side of the tree, after Raphael; lettered state, 1814, etching and engraving, 54.2 x 41.1 cm, British Museum, London

The fundamental error of the Fall is to place human authority and judgement over God's. It is solipsistic, in that it makes the self the arbiter of reality, and idolatrous in that it places that self in God's place. Philosophically, we can express God as ultimate reality or being (the fundamental essence of everything), which means that in empirical terms, the Fall is a failure to live in accordance with reality as it is knowable to us, or the objective truth. The consequence of this is overvaluing our limited perspective and believing ourselves to be the natural masters of ourselves or reality. All the horrors that have arisen from all the utopian fantasies throughout history originate in the arrogant fallacy that human reason can reach absolute truth.

John Faed, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, ca. 1880, oil on canvas, Cleveland Museum of Art

After the Fall, humanity is cut off from timeless truth by our fallen natures, and now see through the glass darkly. This condition is not the same as Postmodernism because it does not reject the existence of the transcendent, only the ability to see it clearly.

Hence the hermeneutic problem and the need for interpretation. The issue becomes one of authority. Which interpretation is the correct one?

If we recall what Aquinas said in the last post, he was describing something we've all experienced: one word or phrase connoting a meaning other than its literal one. Note the use of the word "type". This references typology, a form of Bible interpretation that seeks these analogies betweenTestaments.

Christian typology begins during the assembly of the two Testaments, as a means of tying them together theologically. By this method, events in the Old are interpreted at prefigurations or "types" of things that take place in the New. Numeric concordances are common - forty days and nights of rain in the Flood or forty years wandering in exile prefigure Jesus' forty hours in Gethsemane - but they can be thematic as well. The sacrifice Isaac foreshadows that of Christ, right down to the replacement sheep referencing the Lamb of God.

Sarcophagus of Jonah (detail), c. 300, marble, Vatican Museums

Jonah was a common type for Christ, with his three days in the belly of the whale before returning to the world prefiguring Jesus' three days in the tomb before rising. The sculptor includes Christ raising Lazarus in the upper left so the message of resurrection is clear.

Given the age of this sarcophagus, it is obvious that this isn't new thinking.

This evolved into the four-fold system of allegory of the High Middle Ages introduced in graphical form in the previous post and condensed here. The three levels of meaning after the literal combine to create a universal framework for practical application.

The typological level addresses the problem of the complicated origins of the Bible by tying the Testaments together into a coherent whole. The tropological guides the application of Biblical passages to individual life circumstances, while the anagogical allows for speculation on matters beyond objective experience.

This is a flexible basis for a value system, but it is not without constraints. The interpretations aren't unrestricted or random but associative connotations of other things, or metaphor and not metonymy, in rhetorical terms. Allegorical meanings cannot contradict what is contained in the literal meaning of a passage; they can only enrich it. One need not follow Aquinas' terminology exactly to see the need to adapt to shifting times and apply Christian ethics to things not mentioned in the Bible.

Life of Antichrist: Conversion of Jews; Antichrist send his Preachers all over the World; Disciples preach to the King of Egypt, the King of Libya, the Jews and the Queen of the Amazons, c. 1420, from WMS 49. Apocalypsis S. Johannis, Wellcome Library, London

Hermeneutics is just a technical word for the process of interpretation that the imperfect nature of Biblical signification requires by its own declaration. How does one avoid conmen and charlatans? Through wisdom and tradition.

Though arriving near the end of days, the Antichrist and his disciples represent the archetypal false prophets. Their manner and appearance resembles Christ and his followers superficially, but their goal is to usurp the natural order for power in this world. Notice how, in the top panel, the Antichrist marks his converts beneath a statue of himself. This is the crux of misdirected Satanic solipsism; turning oneself into an object of worship in an act of what could be called auto-idolatry. Christian images point to absent heavenly beings.

The Bible warns against false prophets in a well-known passage worth considering at length:

By their fruits we will know them is a great example of the allegorical figurative language of the Bible. It is also as clear a call for empiricism and objective judgment in the affairs of this world as can be imagined, and a far cry from the hypocrisy and slippery rhetoric of the Postmodernists. Tradition offers a check on wild speculation, as it is a collective history of interpretation and discernment, tested against the source and refined through experience as it moves through time. We can now see the absurdity of positing a single definitive "Biblical" Satan as the last word for Christians everywhere. Artists have certainly been under no obligation to recognize a consistent "look" for Satan. How could they? No one knows what he looks like. What is required is to find an appropriate representation of the inversion of God's natural order and embrace of dark desires. Consider the following images:

So what if Satan does not have a fixed identity? Christian allegory would see him as an historically evolving expression of the basic reality that evil exists as a opposite force to the natural order. Words can no more signify the fullness of this idea any more clearly than any other supernatural notion, so we are in the situation of interpreting blurry pictures in the darkling glass. The image or conceptualization of Satan is a hermeneutic adaptation of something impossible to know clearly to a particular historical context that must shift and change over time. So how do we identify the Satanic? Perhaps listening to the Bible and considering the "fruits" hanging from these disparate representations will reveal a common pattern by which the Satanic can be recognized.

We will briefly look at the Satanic from four arbitrarily defined periods of history: the Old Testament, the New Testament, the Early Christian period, and the Middle Ages. Unlike biased scholars, the Band follows St. Thomas in recognizing that interpretations do not have to be present in the Bible verbatim to be legitimate, but they can't contradict the literal meaning. Legitimate post-Biblical representations actually help clarify Christian concepts that are signified poorly in the Bible itself.

Old Testament

Satan's identity is not fleshed out in this book, and key aspects of his story, such as the rebellion in heaven and the fall of the rebel angels not part of the original text. Historians like to note that the Bible doesn't specifically label the serpent in the Garden as Satan as a sort of gotcha that proves Christians don't understand their holy texts.Then again, we've already seen their level of commitment to granular, nuanced truth.

Gustave Doré, Satan and the Serpent, 1866, engraving for Paradise Lost, Bk. 9, 182-83 'Him fast sleeping soon he found, In Labyrinth of many a round self-rolled'

Doré's engravings for Paradise Lost are a monumental work of art in their own right. Click here for a copy of the poem with the illustrations.

There is a good reason why the weight of Christian exegesis links Satan and the serpent. Remember Matthew? By their fruits shall you know them? The serpent induces Adam and Eve to place their own will and authority above God's, meaning its agenda is fundamentally Satanic. It is simply another representation or interpretation of the core spirit of solipsistic greed that haunts the human condition.

The Satan in Job works with God's approval, but the test he subjects Job to is intended to turn him from his faith. The name Satan is Hebrew for adversary, which clearly denotes a position opposite to the divine order. Even if he worked with God's blessing to test humans, what he advocates is to follow your own council over aligning with reality. If God is the objective measure of Good, then his adversary is relationally evil by necessity.

William Blake, Satan Smiting Job with Boils, based upon Job 2:7: "and smote Job with sore Boils from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head", 1821, number 6 in the Linnell Set of illustrations to the Book of Job, watercolor, 29.0 x 24.0 cm, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge

If God is the ultimate source of all that is, He is by definition "Good", making an adversarial or opposite position "Evil" by the same logic. This isn't a "non-Biblical error" but a clearer interpretation of Satan's essential nature.

New Testament

Satan is referred to more prominently in this book. When considering the relationship between these appearances and his role in the Old, it is important to remember the typological relationships that went into the assembly of the Bible in the first place. The New Testament isn't the sequel to the Old, like a new season of a tv show, but the fulfillment, or as perfect a version as possible of the truth of things previously hinted at. To treat characters in the Gospels as picking up, or even rebooting, Old Testament models is a complete misunderstanding of the formative logic behind the text. Contra dissembling historians, the Hebrew notion of Satan is no more relevant to the Christian one than the image of Yahweh strolling through the garden and chatting with Adam is to the utter transcendence of God.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Allegory of Law and Grace, circa 1530, woodcut, 10 58” X 1’ 34”, British Museum

From a Christian perspective, the New Testament is the more perfect vision, and when it seems misaligned with its predecessor, it takes precedence. Cranach captures the contrast between the salvation promised through the sacrifice of Christ and the road to death and damnation paved by adherence to the old Law in an age of Grace.

Ary Scheffer, The Temptation of Christ, 1854, oil on canvas, 222.5 x 151.6 cm, Walker Art Gallery

When Satan tempts Jesus, he takes the opposite path as with Job, offering worldly things in exchange for turning from the truth. Jesus obviously passes the test, but had he failed, the sin would have been to place his own authority and station in this world above God's law.

Scheffer's painting does an excellent job in differentiating the worldly blandishments of one with the resolute transcendent focus of the other.

Master of the Rebel Angels, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, circa 1340-45, oil and gold over canvas on wood, 64 x 29 cm, Louvre Museum, Paris

The Satan who Jesus saw fall from the sky in Luke is later interpreted as the Fall of the Rebel Angels, a narrative that extends, but does not contradict, the literal meaning of scripture. The former Lucifer's sin was the by now familiar one of choosing in Milton's words, to "rule in hell rather than serve in heaven."

The scriptural passage: "And he said unto them, I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven." Luke 10:18 King James Version

Note also that the devils fall to a round earth in a mid-fourteenth century painting. Some Postmodernists hold that medievals believed the world flat. By now, it should be depressingly familiar that they are wrong.

Post-Biblical

The connections between Satan, the Fall, and Hell form during the Patristic era (the early Christian centuries) and mature over the Middle Ages. St. Augustine (354-430) divided humans and spiritual beings into a City of God and an Earthly City based on whether they align with God and the divine order, or turn to empty worldly ambitions and desires and fall into damnation. By placing control of this world in the hands of Satan and his fallen angels (devils), Augustine laid the theological foundation for visualizing the idea of the "adversary" as a shriveled ontological inversion of God's natural order. This formation is not literally cited in the Bible, but is extrapolated from things that are rather than just made up. Satan is not only the adversary, but Jesus also refers to his enemy as "the prince of this world" (John 12:31).

Michael Pacher, Saint Augustine and the devil, outside of the right wing, lower scene of Kirchenväteraltar (Church Fathers Altar), 1471-75, oil on panel, 103 × 91 cm, Alte Pinakothek Munich

This painting reflects a legend from Jacobus da Vorraigne's Golden Legend, a medieval collection of miracle tales that was one of the most popular books in the Middle Ages, but largely discredited in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In this legend, St. Augustine was confronted by a devil with a book containing the names and transgressions of sinners and tricked it into revealing his one unatoned for fault. While the details of this story are a folkloric invention, it visualizes a simplified form of Augustinian theology, with the devil in charge of the roster of sinners inhabiting the Earthly City.

This symmetry between the blessed and damned is reflected in what may be the earliest known representation of "Satan."

Dividing the sheep from the goats, early 6th century, mosaic, Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna

Satan appears as an angel to the left of Christ while he separates the sheep from the goats, or, metaphorically, Christians from sinners. The notion of an angelic personification of the damned does tie the idea of fallen Lucifer as prince of this world, if this world is understood as turning from the divine order into solipsism.

Over time, Satan develops a more monstrous appearance, drawing on a variety of influences from medieval creatures to the Greek god Pan, but the association with goats remains constant. Pan and the satyrs were debauched earth spirits given to carnal pleasures represented as being half-goat, and this combination of the Biblical association of goats and sinners with the archetypal non-spirituality of the goat-men likely proved irresistable to medieval artists figuring out how to represent this being. Especially when monsters in general were shown as unnatural combinations of animal and human parts.

Last Judgment (detail), between 1240-1300, mosaic, Baptistery of Florence

The terrifying devourer of the high Middle Ages was the basis for Dante's Satan, an immobile giant in the center of Hell, perpetually consuming the souls of history's greatest traitors. This image turns him into a perverse parody of God in the middle of the Empyrean Rose, and reveals the hideous truth behind his claim to self rule.

The image of Satan in Milton's Paradise Lost summarizes his long history in an influential form with a sort of tragic hero felled by pride. Milton, like the Bible, is self-consciously allegorical, since his goal - to justify the ways of God to men - is likewise impossible to signify directly to fallen minds. He presents the fall of Lucifer from the greatest of the angels to lord of Hell as a consequence of the now familiar choice to reject God's order (ie. reality) for personal desire and ambition. The more he willfully turns away from reality, the more evil and inglorious he becomes. This primordeal fall into pride and conceit becomes a template for Adam and Eve's later transgression. Though pressured by Satan, they also opt to pursue their desires over God's, and so too set themselves up as a false unnatural authority. Near the end of the poem, human history is foretold as a series of self-centered tyrants in an endless, meaningless cycle, each repeating the solipsistic error of the Fall on the path to Hell.

Gustave Doré, Satan, Sin, and Death, 1866, engraving for Paradise Lost, Bk. 2, 648-649 'Before the gates there sat, On either side a formidable Shape'

Is Milton's Satan "authentic"? It is true that the character and events as described in Paradise Lost are not in the Bible literally, but the Bible is a darkling glass, and what it shows cannot be precisely understood. Milton's Satan is consistent with the limited accounts in scripture and subsequent interpretation; like Dante, more extrapolation than invention. The creation of this character is an example of the hermeneutic process, where the blurry truth in the Bible is fleshed out in terms more comprehensible to a contemporary audience. But the underlying idea of an adversarial position to God's natural order is as old as the devil himself.

Guillaume Geefs, Le génie du mal (Lucifer of Liège), 1848, marble, St. Paul's Cathedral, Liège

The Romantic era complicated the figure of Satan by recasting him as a sort of hero. This may sound bizarre until we remember some key features of the intellectual culture of Romanticism. This was an emotion-driven rebellion against both the aristocratic/ecclesiastic culture of the ancien regime and the rationalism of the Enlightenment. Christianity was characterized as a regressive tool of social repression and Satan became at least sympathetic as a rebel against authoritarianism. Because as we've seen, "freedom" from rules never leads to wallowing in debasement...

This was the orifgin of the nineteenth-century notion that Milton was of the "devil's party"; and sympathized with Satan's desire for self-determination. After all, Milton had staunchly opposed the monarchy during the English Civil War and interregnum, and was especially hostile to the idea of the divine right of kings. A close reading of the text dispels this, but there is no limit to the ability of humans to project their own desires onto anything they choose. The irony is that Satan's fall, preferring one's own authority to the natural order, is one they repeat. And as far as Milton was concerned, there was nothing Satanic about rebelling against Charles I.

William Marshall, Frontispiece to Eikon Basilike: The pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in his solitudes and sufferings', 1649, engraving and etching, 26.6 x 16.7 cm, British Museum, London

This Royalist image cast the executed king as a pious martyr (the emblems include a crown of thorns), and infuriated Milton, who published his own Eikonoklastes in Answer to a Book Intitl'd Eikon Basilike in response. In Paradise Lost, prideful faith in one's own authority is the archetypal sin, making it is Charles, with his illegitimate claim to worldly power, who replicates Lucifer's error.

The empiricist perspective of the Band precludes speculating on the accuracy of historical representations of Satan, since the true nature of this entity is beyond objective determination. What is not out of reach is an assessment of how these ideas play out in the real world. Christianity begins with a confrontation between human finitude and transcendence in their coming together in Christ, and the need to accommodate this is present in the Bible from the outset.

|

Gustave Doré, The Eternal Regions, 1866, engraving for Paradise Lost, Bk. 3, 347-349 'Heaven rung, With jubilee, and loud Hosannas filled, The eternal regions'

Doré accommodating transcendence.

|

But in this world, our limited intellects are all we have. "By their fruits..." is a call to empiricism - evidence and judgment. How different this is from oppressive secular transcendences that command obedience to dishonest constructs with increasing violence. Christian epistemology recognizes the objective reality of empirical limits, while Postmodernists, like historical peddlers of false faiths before them do not. Only one fails Popper's falsifiability test, for what that's worth.

Coming back around to the beginning of this post, we can identify what it means to be Satanic empirically.

So, is Postmodernism Satanic?

Yes it is.

Gustave Doré, engraving for Paradise Lost, Bk. 6, 874-875 'Hell at last Yawning receave'd them whole', 1866

This post will wrap the epistemology/historiography for now. We'll come back around to it in time - a post (or posts) on reading Derrida is definitely in the future - but was necessary to at least begin to untangle the larger lies that Postmodernism was built on before moving to more specific topics. The next post will begin to consider Postmodern architecture, which will take some unravelling to understand how

French design went from this;

Sainte-Chapelle 1241-1248, Paris, France

to this:

Le Corbusier, Unité d'Habitation, 1947-52, Marseilles

No comments:

Post a Comment