Venice - the Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia - is a small but long-lived entity with oversized influence on the Arts of the West. And some truths for organic community as well. Let's take a look.

If you are new to the Band, this post is an introduction to the point of this blog that needs updating. Older posts are in the archive on the right. Shorter occult posts and other topics have menu pages above.

Comments are welcome, but moderated for obvious reasons. If you don't see it right away, don't worry. We check regularly and it will be up there.

Jacopo Bellini, The Annunciation, 1444, tempera on panel, Sant'Alessandro, Brescia

Venice is a unique entity - really an historical anomaly for it's longeviety, stability, small size, and underrated cultural influence. It's part of Italy but with a distinct history and culture that impacts artistic developments all over Europe. The Band hasn’t looked at Venice in the historical posts because it’s not that big a place. Nor does it steer major currents of events. But we can't approach the Renaissance in northern Europe or the art of post-Renaissance Italy without it. Plus it's super interesting. Perfect for an Arts of the West post to keep us moving towards that 1913 target..

Start with some distinguishing starting features, then trace the art. We'll note some lessons for organic community along the way.

Unique geography

Venice was founded on islands in a lagoon on the coast of the Adriatic Sea for safety. It was resource poor and never had much arable territory, but was secure in turbulent times. Eventually there was a small empire and some mainland territories, but relatively minor compared to it's powerful rivals. The wealth and influence that made Venice a cultural powerhouse came from maritime trade - the one natural advantage given the location.

"Modern" Venice developed slowly - we use that adjective most broadly given the length of the Venetian Republic. We mean that the Rialto Islands that make up the heart of the city today were not the same as the initial 6th-century settlements. The coastal area includes considerable swampy wetlands with limited options for building and high risk of disease. But over several centuries, the linked island city developed.

The Venetia ~840 AD

The ringed dot is where modern Venice is located. Note the neighborhood - between the rising power of the Carolingians and the declining Byzantine Empire. This gets worse when the Ottomans replace the Byzantines.

The unique geography made a maritime focus inevitable if Venice was to survive and prosper. A strong navy was needed to defend the city since the inaccessible location made it quite secure from the landward side. Economic growth was also directed seaward. Without much land to use, foreign trade was the logical outcome. This made it an integral link between Europe and Byzantium, the Muslim world, and the Spice & Silk routes beyond. Tremendous wealth and a variety of outside influences followed. Isolated location plus foreign trade made the Venetians the most insular and most cosmopolitan people in Europe and the Middle East at the same time.

You can see it in their treasures. This and other pieces from the San Marco Treasury were taken from this informative catalog. If interested, it's free online and packed with information.

Rock Crystal Cruet, 10th century Fatimid stonework, 13th century Venetian metalwork, rock crystal, silver gilt, niello, Treasury of San Marco, Venice

Medieval Muslim crystal carving was widely valued. Here's a piece of rock crystal cut like glass from the Fatimid Dynasty of around the 10th century with fine Venetian goldwork added in around the 13th. Venetian trade and foreign adventures brought access to things not seen in the rest of Italy.

The carved crystal is worth a closer look. We don't know how these were made, but it was probably similar to the glassworks the Muslims developed out of their ancient Roman heritage. Only instead of blowing a vessel and then carving and grinding it, they must have carved the whole thing from a large piece of crystal. Considering how brittle crystal is, sanding and grinding were probably the main techniques.

This unique location gave the city it’s most famous feature – the canals that run through it. Amsterdam and St. Petersburg may have more miles, but there is no more famous a canal city as Venice. The proximity to water on every level seems connected to the taste for light and bright color that dominates Venetian art and aesthetics.

Unique history

The unique geography is connected to the unique history of a wealthy, marine city-state. Although Venice stands out for it's long history, it's pretty new by ancient Italian standards. The city was founded in the aftermath of the end of the Classical world - possibly the site of a 5th-century trading post, with significant settlement starting in the 6th century. One of the most important aspects for our Arts of the West posts is the lack of classical heritage compared to the rest of Italy. There were no grand classical ruins or sculptures being dug out of the ground to inspire builders and artists. There weren't even majestic early Christian / late Classical monuments like in Milan or Ravenna.

Most are familiar with the first waves of barbarian invasions like the Huns and Goths that first overrun the Western Empire and sack Rome. Theodoric the Great even founded an early 6th-century Ostrogothic kingdom that tries to fuse Classical and Gothic culture. After it was destroyed in wars with the Franks and especially the Byzantines, a less-famous second Germanic invasion occurred.

These later-arriving Lombards defeat the drained Byzantines and further ravage the peninsula. It was this that drove the founding refugees of Venice to establish their first secure settlements.

The inaccessible lagoon location offered protection from the destruction of the Byzantine-Lombard wars. More complex social structures developed organically. Over the 6th-7th centuries, the individual lagoon communities came together for mutual defense and this evolved into unified administrative structures. In the early 8th century, the first doge or "duke" was elected beginning over 1000 years of Venetian government. Circumstances improved somewhat - the Lombards were eventually smashed by the Franks, and after surviving a brief siege from the Carolingian king Pepin, Venice independence was established.

Over the 8th and 9th centuries, Venice expanded seaward with bridges, canals, fortifications, and other stone buildings. It was at this time that the Rivo Alto or Rialto island group - the heart of modern Venice - was settled.

Antonio da Ponte, Rialto Bridge, 1588-91

The famous 16th-century Rialto bridge continues the long process of living across linked islands and waterways.

With the Franks imposing a period of relative order, Venice thrived as a Byzantine-friendly outpost with a Catholic faith that could play ball politically. It was always unique. But it also offers food for thought for those considering organic communities in another era of looming collapse. We are not at the same point of upheaval, but one hardly needs to be Nostradamus to see a future where continued conflict between opportunistic factions and ravaged countryside is the norm. What made Venice so successful and long-lasting?

1. Security

The site was chosen because it was not just easy to defend. It was hard to attack in the first place.

Pepin likely died of a fever he contracted campaigning in the pestilent swamps on the edge of the lagoon. Lack of material value made sustained assault not worth the cost.

2. Faith

The Venetians shared a strong Christian faith that become woven into their cultural life. Civic rituals like the marriage to the sea were done under the watchful eyes of the Virgin Mary and St. Mark.

Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore

Over time wealth would prove corrupting, but shared faith was the foundation to build an insanely patriotic and united community and culture from less than ideal starting materials.

3. Economic rationality

Venice didn't have mineral or land wealth, but embracing a maritime identity brought the means of long-term survival. Set aside the immense wealth - that was good fortune. Any viable community needs a foundation to provide for itself.

Anonymous, Marco Polo leaves Venice on his travels to China, painted c. 1400, Illumination on parchment

One of the massive failures of the beast system was failing to do so - soulless suburbs and beleaguered towns stripped of the ability to provide for future generations. Fishing and trade worked for Venice. Any organic community will have to find comparable.

4. Organic culture follows organic community

The cultures the refugee founders came with were replaced by their new Venetian identity. Because the circumstances driving the culture changed. Clinging to the corpse of what was is "conservative" idiocy. Organic community builds off the past but it builds. It creates and moves forward. Meaning it responds to the reality it occupies and not sterile beast media and dancing lights. A secure, faith-based, viable organic community will generate organic culture over time.

What does building the new off the values of the past mean? Not trashing heritage and lying about year zeros and blank slates. Here's Venice again. Consider the body of St. Mark

Jacopo Tintoretto, Finding of the Body of St Mark, 1562–1566, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

According to legend, the remains of the Apostle Mark were smuggled out of Muslim Alexandria by Venetian merchants and brought to Venice in 828.

It was common to want to tie a site to a major Biblical figure. Rome had Peter and Paul. Milan claimed to be founded by Bartholomew, and Ravenna said St. Apollinaris was a disciple of Peter. Mark gave Venice a high-end patron of their own.

The story of St. Mark's body brings together the old and the new. The authority and prestige of Mark goes back to the Bible for Christians. There really are no other figures who outweigh him in the traditional value system. But the protagonists being seafaring merchants, the transport coming by boat from a foreign trading partner, and the establishment of a new center well after antiquity are all connected to the Venetian experience. They build a divinely blessed identity off the ancient foundations of Christendom that reflect and legitimize their distinct culture. To repeat...

Between 998 and 1000 the Venetians defeat and suppress the pirates operating off the Dalmatian coast for good. This gives them primacy over the Adriatic and begins their economic ascendance. There are ups and downs - defeat of the Byzantines, rivalry with Genoa, the threat of the Ottomans, new powers like Holland and England. Venice slowly declines as modernity approaches until Napoleon brings their independence to and end in 1797. In 1866 the city became part of the new state of Italy - better perhaps than a French Empire, but less favorable than their old Republic.

This unique history meant it was further removed from the Roman material legacy than other parts of Europe. It wasn’t an ancient center, so Classical influences weren’t present in the same way as Milan, Pisa, Naples and other cities. More accurate to say it trickled through Byzantine filters...

Book cover with Christ, late10th-early11th century, silver-gilt on wood, gold, enamel, stones, pearls, Treasury of San Marco

Venetian machinations around the Sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade brought a trove of loot to the city. But there were plenty of other Byzantine goods available as well. Note how Jesus is derived from Classical contrapposto but flattened and stylized in a Byzantine way. Different from the first-hand knowledge.

...and the occasional surviving luxury object.

Glass situla with Dionysiac scene, 4th century?, glass, silvered bronze, Treasury of San Marco

Some late Roman glass work with mythic sculpture was the sort of thing that was available. Indicative of Classical myth and art but hardly the basis of a Classically-inspired culture.

When it comes to the humanist culture that drove the Renaissance, Venice is somewhere between the North and the rest of Italy. Italian language and geography meant that late medieval humanism did find uptake before it did in Germany, France or the Netherlandish world. But like those places it was consciously imported and grafted onto an already vital local culture. Like everything Venetian, Venetian classicism – and the Venetian Renaissance – was unique.

Unique politics and socio-economics

Venice was known for its stable government - it's where the Serenissima nickname came from. Things did change and evolve gradually, but the rulership of the Doge and various representative elite councils remained the same. Family ties mattered for power, but the Doge and other positions were elected by select stakeholders. Hence the Republic title, but broad oligarchy is probably more accurate. When the Council of Ten rose to prominence in the later Renaissance, it was more oligarchic in the typical sense.

The Doge's Palace or Palazzo Ducale, begun 1340, Venice

The Doge was a quasi-mythic figure who embodied the city in some ways. He was elected for life and had tremendous power, but was also limited in specific ways and subject to law. The first doges were elected by the clergy in the 8th century, then more formal structures developed.

The 26th doge, Pietro II Orseolo (991–1009) defeated the Dalmatian pirates on Ascension Day in 998, and two years later a new tradition began. Starting in 1000, the doge and local bishop would bless the Venetian navy, and this developed into the ritual called the Sposalizio del Mar (Wedding of the Sea). This became a sort of marriage ceremony between Venice - represented by the doge - and the all-important sea. The doge would sail out in a golden gondola called the Bucintoro and throw a ring with the Latin inscription Desponsamus te, mare (We wed thee, sea) into the water.

Canaletto, The Bucintoro at the Molo on Ascension Day, around 1745, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Later depiction of the Sposalizio preliminaries in front of the Doge's Palace.

The Doge held his title for life, but this was not considered a grant of divine right or heredity. His legitimacy was rooted in the trust of the people, and it was from the prominent families that the supporting and restricting system of government developed. This eventually becomes a complex network of governing bodies intended to maintain checks and balances. By 1300, the Great Council was made up of 1,000 men drawn from a list of 180 noble families.

Joseph Heintz the Younger, The interior of the Sala Maggior Consiglio, The Doge's Palace, Venice with patricians voting on a bulletin for the election of new magistrates, 1648-1650, oil on canvas, private collection

18th-century painting of the Great Council meeting in the splendid Sala Maggior in the Doge's Palace.

And the Sala Maggior today. The decorations are oil paintings on canvas set into gilded frames instead of the typical Italian frescos. Renaissance Venice was famous for its oil painting and the damp climate made frescoed plaster impractical. The painting at the far back wall is Tinteretto's Crucifixion, the widest painted canvas ever.

Venice got away with it's openness to foreign commercial interests by strictly limiting participation in government to a list of established Venetian names. If you didn't belong ot the 180 or so families you could trade in Venice - even stay there - but you had no vote and couldn't serve on the councils. And the Great Council elected the Doge, Senate, Quarantia, Council of Three, and other ruling bodies. In 1323 the book of names was closed meaning no new families could ever be added. This ensured that Venice could only be ruled by longstanding Venetian patricians. Those with the most skin in the game.

Here's another rule for organic community...

5. Rule by your Own.

Venetian government moves into oligarchy with the ascent of the Council of Ten. This body was formed out of the Grand Council in 1310 and was - with the Doge - the main power by the turn of the 17th century. But the closed book of families ensured all these individuals were old Venetian. And that brought connection to the city, its history, culture, and traditions that is far beyond the globalist rent seekers of the modern beast system.

Domenico Tintoretto, Doge Giovanni Bembo kneeling before the personification of the City of Venice, 16th century, oil on panel, Doge's Palace

The central idea in this celebration of the Venetianness of the doge. It isn't rhetoric - he was required to come from old Venetian stock by law.

Venice may not have fit the modern notion of republic with universal sufferage, but it was Venetian. You can have individual greed or self-interest, but it avoided the wholesale turning against the people for outside interests. This image of self-directed "republican" city-state inspired other commune governments in Italy, like late medieval Milan, Siena, and Florence. The Band would argue that enforced local rule with at least an ideology of popular support gave Venice the confidence in its legitimacy and self-interest to defy powerful outsiders. Including the papacy.

Along with unique government came a uniquely trade-centric economy. The Venetians had little to offer of their own, but brokered and transported large flows of goods.

Map of medieval Venetian trade routes at the peak. These came with outposts and warehouses in different regions.

The Ottoman's takeover of eastern routes was almost as much a threat to Venetian prosperity as direct attack.

The Venetians benefited from a number of Byzantine privileges starting with the10th-century Grisobolus or Golden Bull. This freed Venetian traders from Byzantine taxation, including taxes forced on Byzantines. Liberties continue up until the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, when Venice essentially ended the empire as a rival. Not only did they gain access to Byzantine trade and treasure, weakening the empire while sparing it's Muslim enemies of a costly attack was a long-term nail in the coffin. The onlly people who benefited more from the Fourth Crusade that the Venetians were the Muslim powers in the Middle East.

Chalice of the Emperor Romanos II, stonework from 3ed-4th century, metalwork from 959-963, sardonyx, silver-gilt, gold, enamel, and pearls, Treasury of San Marco, Venice

Another treasure looted from Constantinople. It wasn't uncommon to add precious metalwork to older vessels - like the rock crystal cruet above. This one was a late antique sardonyx cup with enamel saints and angels from the 10th century for imperial use.

In hindsight it was probably better it wound up in Venice than destroyed by the Ottomans in the 15th century. Though had the Fourth Crusade actually crusaded... their lack of cohesion and professionalism probably would have gotten them smoked by the Seljuks. But that gets into alternative histories.

Venice was known to the wider world in ways that its Italian rival states were not. It's ships and merchants were familiar sights in far-off ports and it could afford to be an open trade hub because of its strict local rule. Even enemies did business with the island city. Profit is something of a universal currency

Piri Reis, Map of Venice in the Kitab al-Bahriye (Book of Navigation), 16th century

Here's a map of the city from a Turkish volume on navigation from the Renaissance era. The Turks fought with the Venetians but also did extensive business with them. Venetian traders could be found in Istanbul and other Ottoman ports.

In the 12th-century, the Venetians started what would be the first mercantile exchange business to broker goods and capital. They also founded the Venetian Arsenal - an innovative shipyard that built vessels along a proto-assembly line instead of one at a time. The Arsenal obviously wasn't mechanized, but the sequence of specialized constructions allowed them to produce ships at a far faster rate. This was the secret to a small place with limited space and manpower maintaining such an outside marine presence. The Arsenal process cranked out production at the speed of a much bigger state.

The gate to the Arsenal today. It was a walled area that occupied the eastern seaward part of the main islands. Access was carefully guarded to prevent rivals from learning the process.

6. Security is Viable in an Organic Community

The Venetians were well aware that people who weren't Venetian didn't have the same care for Venetian prosperity and security that Venetians did. There were always large foreign factions in the city, but just as they couldn't rule, they couldn't access the Arsenal either. And yes, this means that wages may have been a bit higher than rock bottom. On the other hand, the Arsenal remained a unique advantage for centuries. The modern plague of divided loyalities - rule by "dual citizen" would have been inconceivable to medieval or Renaissance Italians.

Map of the Arsenal process from an interesting website. Vessels moved along the channel and built in installments at each station. It was many times faster than standard construction.

In many cases, their self-directed, self-serving focus made the Venetians disliked by neighbors and rivals. But relentlessly pursuing its own interests is what the rulership of an organic community is supposed to do. It's not like other powers were considering what was best for Venice. Whether this meant over a century of clashes with Genoa that ended in 1381 or a negotiating a trade treaty with the ascendant Mongol Empire in 1241, Venetian interests worked for the good of Venice. They didn't always make the right moves and could put themselves as individuals first on occasion. But consider the alternative...

The defining unity of faith, distinct government, and relation to the see is visible in the layout of Venice itself. Consider the symbolic heart of the city.

The Doge's Palace was built next to San Marco, the main cathedral. The cathedral plaza - the Piazza San Marco - extended from the front of the church, but note the smaller Piazzetta at right angles. It was where justice was administered and bounded by Palace, San Marco, the main Library, and the sea.

You can see it here in the Piazzetta San Marco from both ends. The square is bounded by the symbols of Venetian authority and identity with the sea being one of them.

It's all right here to be taken in at a glance - the unique history and culture written in the cityscape.

That's Venice coming into the Renaissance - a small, rich, fiercely independent seafaring nation that grew out of humble origins in an inhospitable place. There are lots of lessons there for organic community in the future as we head into another post-imperial aftermath. Ultimately the system was eclipsed by the rise of the European nation-state and the mass-scale advantages of early modernity. But consider the difference between that world and its post-antique founding. We'd say their experiment was quite the success.

With money to burn and a unique culture, no wonder Venetian art follows its own distinct path. The rest of this post will trace some key developments in the art of Venice with an eye to the impact on the Arts of the West.

Byzantine Influences

The art of Byzantium had a much greater effect on Italy then the rest of Europe due to historic ties and geographic proximity. This was much greater in Venice then elsewhere.

Icon of the Archangel Michael, 10th century, enamel and gemstones, Treasury of San Marco

Masterpiece of middle Byzantine gold and gem craft in icon form. Icons had a specific status in the Eastern Chruch that they didn't have to Western Catholics, but the panel picture form was influential. Panel paintings weren't common in the early medieval West compared to wall art like fresco and earlier mosaic. Byzantine icons inspired Italian painting in the later Middle Ages.

Venetian art went further in adopting Byzantine taste for shining gold and gems and rich full colors. The aesthetics of the St. Michael icon - glittering light, intense, saturated hues - perfectly captures the main characteristics of medieval Venetian art.

There's nowhere where this Venetian taste for color and light comes through more than the cathedral of San Marco. The current church was started in 1063 to replace an outdated older structure and symbolize Venetian wealth and importance. The showcase cathedral was another innovation that would catch on around Italy like the republican government. Siena, Pisa, Florence, and Milan are just a few of the city-states that would announce their significance with spectacular civic cathedrals from the 12th-14th centuries. San Marco was unique for it's Byzantine-derived plan.

San Marco wasn't exactly the same as a Middle Byzantine Greek cross-shaped plan because the nave was a little bit longer than the other arms. It's visible on the plan. This was to provide space for ritual processions important to the Venetian church.

But the inspiration in the Greek cross with five domes shape is also obvious. Especially the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople.

San Marco with the Doge's palace and Piazzetta San Marco. The cathedral was essentially the Doge's palace chapel for most of its existence and he was granted certain ecclesiastic privileges despite his lay status. In 1251 Pope Innocent IV entitled him to wear a mitre and ring and to carry a crosier for certain events.

The tall bell tower is an early 20th-century replacement of the 10th-century original. It's typical of Italian bell towers or campanile for being separate from its church.

San Marco was dedicated to the city's patron Apostle and housed his relics that were stolen from Alexandria. It's religious significance, location, and splendor made it the spiritual symbol of Venetian identity. Discussion of their artistic preference for bright color, gleaming flickering light, and visual impact starts here.

San Marco really is like nothing else...

The interior is covered in gold mosaic spanning centuries. The earliest started shortly after construction was finished and continuing into the 19th century. The effect of the light pouring in and glittering off the golden tiles is breathtaking. The bold colors of the images stand out - almost floating against the gilded radiance. Mosaic was an antique art form that came into it's own in the early Christian period and was the preferred medium for Byzantine church decoration. But there's nothing surviving from any era - maybe nothing from any era period - like the mosaic splendor of San Marco.

Take a look...

Great photo of the play of light on the shining surface of the interior walls and vaults. It's impossible to do it justice in photos, but this at least gives an idea.

If the sunlight glittering on the water is the first "source" for the Venetian love of light and color in art, having San Marco as the city symbol is the second.

Here's another view of the upper arches below the nave dome. It doesn't matter where you look - it's all gleaming surfaces covered in gold and bright colored pictures.

Mosaics were added until the 19th century. Venice never adopted the fresco painting that dominates pre-modern Italian painting. Their own Murano glass industry ensured a source of high-quality tesserae and San Marco offered a steady customer in turn.

7. Organic community makes economic decisions that most benefit the community

Because of the continues addition and replacement, only about one-third of the mosaics are original. Some of the earliest in large quantities are in the narthex - the porch on the entrance side before entering the nave. These start from around 1070 and are pretty Byzantine in style. Most likely due to a lack of skilled Venetian artists to tap at home. Here's a look at it with the intricate tiled floor. The floor is a work of colorful art in its own right.

The Byzantine influence slowly disappears over the 12th century. This is likely due to the Venetians developing their own skilled artists. By the end of the 13th century, the first wave of interior decoration was finished. Here are some old testament scenes including the creation in a narthex dome from the first decades of the 13th century - around 1210

And a look at the Noah scenes just visible in the arch at the top of the above picture.

The drowning crowd is pretty blunt.

The main church is also covered in stories - we can possibly give an overview of the number and eras represented. Here's one 13th-century example showing the martyrdom of the titular saint Mark. The style of the pictures is slightly different but the impression of gleaming gold and bold colors is the same.

The architecture is more symbolic than real - no sense of space beyond enough to set the scene. Mark is celebrating Mass from the altar setting and liturgical elements shown. His hands are in the old orans prayer position.

Note how even these simple elements are covered in colorful decoration. The splendor sort of undermines the horror of the scene.

Nothing concentrates the light, color and splendor of the San Marco experience like the Pala d'Oro. This was the retable - composite altarpiece - behind the high altar in gold, precious stones, and enamels. It dates to around 976 and was expanded in 1105, probably because the original was a bit small inside the new San Marco that started in 1063. In 1345 it got it's final form with the addition of a Gothic-style frame and more stones and gems. The influence of European Gothic would shift Venetian art away from Byzantine models without touching the love of light and color. Here, the different period styles coexist in a single visionary masterpiece.

The Pala d'Oro is almost 10 feet wide and 6.5 feet tall and covered in gold and silver. There are 187 enamel plaques and 1,927 gems. The top enamels include a Life of Christ and date to 1209. The Life of St. Mark below was made in Constantinople in 1105 in Constantinople

Here's the front view of the Pala d'Oro with Christ at center and a ton of saints. Scenes from his life and an image of the Archangel Michael are along the top row.

The central image of Christ surrounded by the Four Evangelists, all in enamel and highlighted with gems.

Below is the Virgin Mary and two other saints. The gold lines on their robes are a Byzantine technique called chrysography. It's not all that realistic, but makes the figures glow in reflected light.

The impact of the Byzantine icon on medieval Italian art was big enough that the term "Italo-byzantine" is used for the style. The Pala d'Oro and San Marco mosaics have some Italo-byzantine qualities but it mainly refers to the icon-like panel paintings that started appearing in 13th-century Italy. They weren't icons in the Orthodox theological sense, but were devotional works of the Madonna or saints that were painted on wood like icons. This appears the be the beginnings of what would grow into Renaissance art after a few centuries.

Not surprisingly, the Venetians had the largest collection of Byzantine icon painting and were especially receptive to the golden backgrounds and saturated colors. Here's an example of an early 13th-century icon from Venice.

Nicopeia Madonna, probably early 12th century, tempera on wood, San Marco, Venice

Icon of the hodegetria - pointing the way - type looted in the sack of Constantinople in 1204. Icons were considered to possess metaphysical properties and fell into very formal categories. The Italians didn't see them this way. To them, they were an appealing form of representation.

Note the symbolic relationships - Mary envelops Jesus because she brings him into the world and points to him. He resembles a tiny emperor in a carry-over from early Christian convention. Faces are very linear and stylized.

The Italo-Byzantine style that derived from icons like this flourished all over Italy. It's especially well-known in Tuscany, where Florence and Siena developed flourishing art scenes out of the new panel painting idea. The proto-Renaissance art of the 13th century, before the influx of Gothic influence was the result. Painters like Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto took the Italo-byzantine template without the Eastern reverence for the traditional icon forms. This freed them from the need to copy faithfully and opened the way to experimentation and innovation. Their interests were more purely artistic - devotional art that worked through aesthetic appeal rather than belief in sacred formulas. The result was rapid growth of realism and emotional appeal. When Gothic influences started arriving, there was already a foundation that would slowly involve into the Renaissance. Earlier Arts of the West posts look at this.

Here's an example of a major proto-Renaissance piece by the Florentine Cimabue that derived from Italo-byzantine roots.

Cimabue, Maestà, around 1280, tempera on panel, Louvre, Paris

This huge altarpiece is almost 14 feet high and dwarfs any Byzantine icon. But the altarpiece type seems to be a Tuscan invention derived from Italo-byzantine roots. Put aside differences in size and usage between an altarpiece and icon and the similarities can still be seen. The stylized figures over a gold background, the tiny emperor version of Christ, the facial types, the tempera on wood technique.

Newer developments in realism and emotional appeal are also visible. Note how all the figures make eye contact and the impression of 3D depth in the figure placement around the throne.

When the Italo-byzantine derived painting comes to Venice shortly after Tuscany, it comes with that same amped up Venetian light and color. Paolo Veneziano is the first proto-Renaissance "name" associated with painting in Venice starting in the early 14th century. His name just means Paul of Venice or Paul the Venetian, so it's hard to say much about his family origins. His art is quite distinct though and really striking.

Paolo Veneziano, Coronation of the Virgin, 1324, Panel, Washington, National Gallery of Art

Compared to the Cimabue, Paolo's painting is flatter spatially and more vivid in its use of color. The chrysography - the gold lines on the robes - linger long after they disappear in Tuscany as unrealistic. They are more radiant, and it seems the Venetian taste for dazzling light and color keeps them around longer. Also note how much gilded 3D texture there is on the surface. The overall impression is not that different from the glittering interior of San Marco.

Another Paolo shows the architectural splendor of large-scale early Venetian painting. This is a type of painting known as a polyptych - multiple pictures in one frame. They were common throughout late medieval Italy, but the Venetian ones are especially extensive and ornate. Again, note the overall impression of San Marco-esque gleaming gold, bright colors, and overall splendor that overrides the appreciation of any one particular scene. Once again, the Coronation of the Virgin is the titular subject, but the real message is light and color.

Paolo Veneziano, Coronation of the Virgin Polyptych, tempera on wood, 1333-1349, Accademia Venice

Gothic influence comes to Venice from northern Europe as it does elsewhere in Italy. Here it is facilitated by trading relations. Here's a smaller panel from Paolo - likely from a polyptych - combining that heightened Gothic emotion we saw in earlier posts with the Venetian taste for color and light. It's unfortunate that polyptychs were generally cut up in later centuries to better serve the art collector market. The big assemblages were altarpieces and meant to stay in one place where the public culd view them. Collectors wanted smaller, portable pieces that better fit the concept of an individual work of art. We are historically poorer for elite greed. How often can we say that.

Paolo Veneziano, The Crucifixion, ~1340, tempera on panel, National Gallery, Washington

Vivid color and light meet Gothic emotion in Paolo's late work. Note the angels catching the holy Eucharistic blood. Remember, the Gothic was driven by a desire to get viscerally closer to God.

Lorenzo Veneziano was the dominant Venetian painter in the second half of the 1300s and may have trained under Paolo. They probably weren't related - his name means Lawrence from Venice, not a surname. Although late medieval Venetian art was dominated by family workshops, so who knows. In any case, Lorenzo worked in other centers as well and brings more Gothic influence into his art. We can see some of the naturalism associated with earlier 14th-century Italian painters like Duccio and Giotto. What doesn't change is the intense decorative richness of the light and color.

Here's one of Loranzo's finest polyptychs. The figure of God the Father in the center is a later replacement for the lost original.

Lorenzo Veneziano, Polyptych of the Annunciation (Lion Polyptych), 1357, tempera on wood, Accademia, Venice

Note the distinct pointed arches of the kind we saw in the Gothic Arts of the West posts on architecture. Here's the central panel up close. The difference from Paolo is more visible here. The tiny figure kneeling on the right of Mary is the donor Domenico Lion - the Venetian aristocrat who paid for the piece.

Note how Mary has more realistic facial features and a body that seems more solidly three-dimensional. There's some early International Gothic gracefulness in her pose and how she and Gabriel interact.

What doesn't change is the splendor of the glittering gold and full colors. If anything, her golden starburst robe is even more splendid than Paolo's chruysography. More realistic too.

Sts. Anthony Abbot, John the Baptist, Paul, and Peter beneath assorted prophets on the left of the Lion Polyptych. It's a good look at the Gothic architecture. The figures are less Byzantine and more Italian Gothic in type.

Around the turn of the 15th century, the Gothic influences in Venetian painting become more pronounced. Niccolò di Pietro is a good example of the increasing ties to other northern Italian tendencies in art as well as northern European International Gothic. The figure types - especially the warm smiling faces in this Madonna resemble contemporary painting in Bohemia. The Christ Child is still

Nicolo di Pietro, Belgarzone Madonna, tempera on wood, 1394, Galleria dell'Accademia, Venice

It's a gradual progression, but easy to see when aware. The 3d qualities of the throne assembly are more spatially coherent. The figures look and interact a little more like real people. Jesus is unnaturally mature - pointing to a text - but looks more like a baby than before. The warm expressions bring the human appeal of the emotional side of the aristocratic International Gothic. It's a similar progression seen in other parts of Italy, but with that Venetian emphasis on bright color and splendor.

Apparently Nicolo's interest in fine luxurious fabrics like Mary's dress can be linked to Venetian trade with the textile centers of the Islamic world.

Jacobello del Fiore was an influential painter around the turn and first few decades of the 15th century. His work combines elements of the earlier style of Lorenzo with some late-stage International Gothic like that of Gentile da Fabriano in Florence. Considering that this was when that remarkable first stage Florentine Renaissance was taking off, it's easy to see why that city was considered so artistically innovative. Not that Jacobello is a bad painter - these paintings show he was actually very good. Just not cutting edge. The Venetian taste for light, color, and splendor is pretty set. The radical shift comes later in the century, and even then stays true to those basics.

Jacobello da Fiore, Crucifixion, 1395-1400, tempera and gold on panel, Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio

Compare this to Paolo's Crucifixion scene above. The figures are more realistic and organized in a spatially coherent way. There's still more emphasis on vibrant colors than narrative realism, but the sense of physical space is developing.

This little devotional panel by Jacobello is a throwback to the simple icon type - Madonna and Child against an undifferentiated gold background intended for pious reflection and meditation. But note the graceful International Gothic realism instead of a schematic Byzantine style. Mary's robes hang in sweeping curves, but fall naturally compared to Paolo's linear folds. The rich fabric indicates Venetian wealth and textile trade with color and pattern and not gold. Jesus is splendidly dressed but looks and sleeps like an baby and not a tiny adult. Venetian art is slowly evolving.

Jacobello del Fiore, Virgin and Child, around 1410, tempera on wood, Museo Correr, Venice

The emotion in the faces is another sign of natural appeal coming from Gothic sources. There is tenderness is how she hold her child. But note the pensive expression. According to tradition, Mary foresaw her son's destiny and her joy in motherhood was balanced by the awareness of his suffering to come.

It's in rough shape, but this is an excellent picture.

One more Jacobello because we'd never heard of him and his art is strange and wonderful. Well worth another look. This big triptych is a later piece - he dies in 1439 - with an unusual subject. It's an allegory of Justice flanked by a pair of archangels. The piece was recently restored and expresses a complex message of Venetian self-importance and identity.

It was painted for the Doge’s Palace in 1421, likely in celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the legendary founding of Venice in 421. Justice was one of the principle virtues that the Venetians claimed as a state ethos.

Jacobello del Fiore, Justice between the Archangels Michael and Gabriel, 1421, tempera on panel, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

The allegory is complex. The figure of Justice in the center has aspects of a personification of Venice as well. According to Venetian folklore, the city fulfilled God's promise at the Annunciation of political salvation to the Christian world after the fall of the Roman Empire. Like Mary, the unconquered Venice was never violated. Gabriel was the angel of the Annunciation and represents peace.

Close-up of Michael on the left with his scales of justice striking down a dragon representing evil. Note the incredible richness of the golden armor and halo.

Michael is connected to the concept of justice because of his role at the Last Judgement. Together the two angels connect Venice, justice, peace, and the legacy of the Virgin Mary.

If there is one artist connected to the transition to an actual Venetian Renaissance style, it would be Jacopo Bellini. He is probably most significant for his family dynasty of painters. His son Giovanni was the famous one who dominated Venetian art in the second half of the 15th century. His other son Gentile was a major artist in his own right and his son-in-law Andrea Mantegna became the influential court painter of Mantua, a Renaissance culture hub. But Jacopo was their teacher and a major break from the Byzantine and Gothic dominated currents we've been looking at.

Here's a Jacopo Bellini piece with familiar golden Gothic ornamental opulence. But there are important differences...

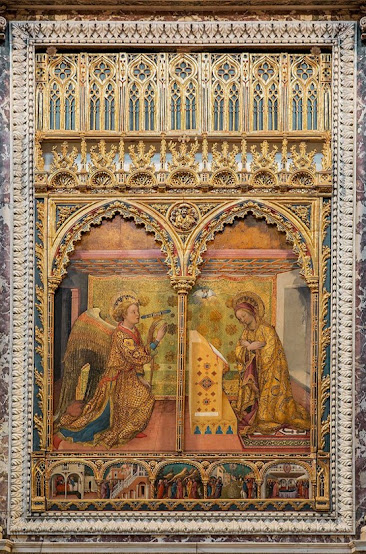

Jacopo Bellini, The Annunciation, 1444, tempera on panel, Sant'Alessandro, Brescia

This piece was recently cleaned, bringing out those vivid Venetian colors. The golden robes worn by Gabriel and Mary are as shiny and splendid as anything that came before. But look at the attitude towards space in the picture. There s a coherent room imagined behind the Gothic arched like something from Florence. Look closer...

Close-up with vivid color. The ceiling and floor tiles recede in a manner that suggests awareness of the new Florentine perspective. Hard to be sure because the vanishing point is behind the central column, but it's not like anything we've seen before. Mary's prayer stand recedes too.

The color is still intense, but made part of an actual environment. The bright background is a hanging tapestry rather than the old gold back. The figures still have Gothic grace, but also a little more solid presence.

Transitional.

The small predella scenes at the bottom show more of this new Renaissance quality. The Dormition of the Virgin is a common scene showing Mary's passing with the Apostles in attendance. But now it's in a deep, perspectival space without even the vivid decoration or costume of the main Annunciation. The colors are rich, but more realistic.

Or The Visitation - when Mary meets Elizabeth when both are pregnant with Jesus and John the Baptist. Here the scene takes place in a landscape. This is another new development towards interest in the real world. Venice would lead the way in Renaissance Italian landscape painting.

There aren't a lot of Jacopo Bellini paintings surviving, but a couple of Madonnas should really make his innovative position clear. What will happen in the Renaissance is that the Venetian taste for light and color will redirect from shiny golden splendor to artistic effects. It's already sort of visible with the full saturated colors in more realistic settings in the Jacopo Bellini Annunciation scenes. But it really takes off after the adoption of oil paint - heightened luminosity, forms built out of color, and powerful contrasts of light and dark called chiaroscuro. Venetian painting becomes more emotionally driven than its Roman and Florentine counterparts, and light and color are the main factors. Jacopo isn't there yet, but look at the contrast in this familiar type...

Jacopo Bellini, Madonna and Child, 1450, tempera on wood, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

It looks like it needs a cleaning, so it is likely that the colors were much brighter than they appear now. The Annunciation above was so dark before cleaning that it looks like a different picture (click on the linked picture for a close-up). Years of oil lamp and candle smoke were bad enough - often well-meaning "restorers" would apply animal varnishes for protection that really darken over time. So ignore the colors - look at the contrast between the figures and dark background. They come forward from the shadows like real people. Light and color in a more artistic sense.

Compare it to the Hodegetria icon that started this trip through history. It's the same basic composition. Mary Queen of Heaven holds the tiny imperial Jesus with a cruciform halo. Her hand is more natural, but still isn't far from pointing. The realism is obviously radically different - Jacopo is the transition to the Renaissance interest in humanistic art. And look at the contrast through light and color. The dark Madonna floating against heavenly gold is replaced by the bright Madonna moving out of a shadowy niche. One more supernatural, one more natural. But both are signs of an enduring Venetian fascination with light and color. Just filtered through changing conceptions of what art is and does.

This comparison brings us to one more point about organic community...

8. Organic culture can adapt to outside innovation on its own terms without losing its identity.

The kernel of truth in the "cultural appropriation" nonsense is that when cultures LARP as something else they don't do anyone any good. Themselves included. Likewise the retarded cultural inferiority complex like the one certain Americans appeared historically to have towards Europe. Collective rejection of ones own culture for any reason is pathological - and unlikely to be a problem with an actual healthy logos-facing culture. Inspiration and new innovations are different. Not least because they don't involve LARPing or rejection. They're adaptive - new ideas but filtered through meaningful cultural structures.

Like the transformative adoption of oil paint...

Jacopo Bellini, The Madonna of Humility adored by Leonello d'Este (or one of his brothers), 1450, oil on panel, Louvre, Paris

There's a lot going on here. Note the appearance of a landscape background. The proportions are off, but the notion that Mary and Jesus are located in a real setting comes through. Jesus is also proportioned even more like a real baby, if unnaturally mature. The identity of the kneeling donor isn't 100% certain, but his cloth of gold marks his noble status. Mary's robes also have delicate golden trim.

The other big change is the use of oil paint. We saw that this had become standard in Netherlandish art in the last Arts of the West post and Venice was the first Italian city to really adopt it.

Jacopo could point to the future, but was too old, limited, and of his time to launch an artistic revolution. That would fall to his followers, especially his gifted son Giovanni - the father of the Venetian Renaissance. We'll tackle him in part two along with the masters of the Venetian High Renaissance. Especially the lordly Titian and a whole new way of painting - light and color's answer to the designs and compositions of Raphael and Michelangelo to the south.

But as revolutionary as he was, Giovanni Bellini didn't do it alone. Remember, Venice was a hub of merchants and travelers, and Bellini worked briefly with a Sicilian painter from 1475-1476 named Antonello da Messina. The itinerant Antonello seems to have absorbed much of the essence of Netherlandish painting without any documented trips out of Italy. It was this flair for oil paint and expression - far beyond anything currently in Venice - that he passed on to Giovanni. Next time...

Antonello da Messina, Virgin Annunciate, early 1470s, oil on panel, Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, Palermo