One of the more irritating aspects of Postmodernism is

the tone of smug certainty, even inevitability, used to describe our supposedly random, fragmented, technologically-mediated culture. It is not only the high-minded theorists and critics that pretend our highly legislated, debt-bloated system, with its endemic corruption and

increasingly transparent legacy media propagandists, is some sort of natural

endpoint in human social evolution. Consider how some will attempt to wish away

biological or material reality by invoking the current year, as if the genome

is carefully watching the Gregorian calendar. Or the breezy condescension with

which we were told to just accept the predations of a slanted global economic system, since the old jobs aren’t coming back. Yet one president, who

many actually consider unfit for the office, has sent manufacturing job

creation and brick and mortar investment soaring with simple changes to tax and

trade policy. If this was all it took, how inevitable was it?

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, The Triumph of the Name of Jesus and Fall of the Damned 1672-85, fresco with stucco figures, Il Gesù, Rome

Illusionism refers to the art of making something appear to be real that isn't. In the past, it was done with optical effects like the ones in Gaulli's ceiling, which make it appear as if the heavens are opening into the interior of a church. Modern illusionism is more subtle; deceptions promulgated through nodes of institutional control and repeated until they are accepted as natural. However, were they natural, the illusionism would not be necessary. Gaulli believed in a vision of heaven that lay beyond ordinary sight. Do the prophets of Postmodern inevitability share similar supernatural beliefs?

The term “Progressive” associates simplified Postmodern politics with perpetual, positive forward movement, but given that our Postmodern existence is supposed to be a decentered web of arbitrary signifiers, how is progress possible? What does it even mean to progress in a world without some sort of transcendent value system to serve as a guide? Postmodernism, as its academic champions are wont to trumpet, is based on theory, but if that is the case, we should be able to evaluate how well these theories conform to the reality they purport to theorize. A theory is merely an abstraction of a pre-existing set of phenomena, and is only valuable to the extent that it enables understanding. In other words, we determine the value of a theory by how well it relates to reality. Given how misaligned it is with human nature and how poorly it correlates to actual events, one suspects that Postmodern "theory" takes a slightly different approach.

Theseus fighting Prokrustes, tondo surround of Attic red-figured kylix, ca. 440-430 BC, London, British Museum

Procrustes was a monster who murdered travelers by stretching or chopping them to fit his bed before Theseus gave him a taste of his own medicine. I suppose he was an early progressive, willing to go to any lengths to smash human diversity into his vicious little box.

Procrustes was a monster who murdered travelers by stretching or chopping them to fit his bed before Theseus gave him a taste of his own medicine. I suppose he was an early progressive, willing to go to any lengths to smash human diversity into his vicious little box.

There is an inherent contradiction at the philosophical heart of Postmodernism that comes from its distant roots in the philosophical idealism of the early nineteenth century and serves as a cautionary tale about what happens when highly speculative academic formulations become accepted as fact by an uncritical mainstream. The problem has Marx’ bloody fingerprints all over it, but the origins go back at least to Hegel’s philosophy of history, which foreshadows Postmodernism in its familiar desire to wish things true that aren’t. His famous process of dialectic, by which new ideas emerge from the synthesis of opposites, is hopelessly naïve in its binary thinking and doesn’t actually apply to any known process of creation. How does one even identify and isolate the constitute opposites in a multivalent, moving entity like the world?

The appeal of Hegel's formula is easy to understand, because it allows you to believe two opposite things true at the same time, which is basically formalized cognitive dissonance. But reality is somewhat less forgiving of incoherent desires. Let’s try some domains where some clearly definable dialectic relationships might be identifiable.

RGB illumination, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License

Secondary and tertiary colours can be thought of as syntheses, but the constituent hues are not opposites, nor are they limited to pairs.

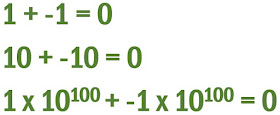

Math deals with abstract values that are ideally precise in their identities and relationships; what happens if we try and synthesize opposites here?

The opposites may be synthesizing, but the new syntheses don't seem producing much in the way of new knowledge.

Maybe scientific analogies are unfair. What about a broad historical structure like the Western Tradition? There are actually three main pillars here - Greek philosophy, Roman Law, and Christianity – plus Germanic cultural traditions and countless internal developments and external influences through trade, exploration, conflict, etc. It doesn't seem all that dialectical in Hegelian terms either.

Music? It is unclear how Hegelian dialectic accounts of the emergence of symphonic music out of the Renaissance or the subsequent Baroque – Classical – Romantic progression. The same holds for literature and the visual arts.

I suppose the exchange of genetic material in sexual reproduction would serve as an example of synthesis, but even this falls apart, since the one place where the two parents are "opposites" - their biological sex - is the one place where the offspring follows one or the other. You get more accurate historiography from a Ouija board.

There are doubtless countless incidents in the flow of human

history where differences are split and compromises found, but these clearly

don’t rise to any kind of larger heuristic value. On a broad scale, there are no instances where Hegel’s formation even remotely resembles

processes of human development and understanding. There is nothing wrong with

this in itself, but it poses an enormous problem for any attempt to use it in a meaningful,

predictive way. It is an annoying commonplace in philosophy and criticism to preserve an obviously flawed

or erroneous structure by qualifying it with the creator’s name, as if that were a talisman that magically compensates for inaccuracy. Suddenly it’s “Hegelian

Dialectic” – loaded with all the authority that accrues when no one reads the source material.

Alchemical Map to the Philosopher’s Stone from Heinrich Khunrath, Amphitheatrum sapientiae aeternae, circa 1595

The Philosopher's Stone was an alchemical fantasy of a substance that could transform base, valueless materials into gold. Formations like Hegelian dialectic and Marxist economics suggest that "The Philosopher's Name" has similar powers in the world of ideas.

The Philosopher's Stone was an alchemical fantasy of a substance that could transform base, valueless materials into gold. Formations like Hegelian dialectic and Marxist economics suggest that "The Philosopher's Name" has similar powers in the world of ideas.

Hegel’s other great toxic fantasy was his “spirit/ghost of history” or zeitgeist; the notion that the flow of history followed a set direction, or teleology, on the broadest scale. Teleology is simply a term that refers to a predetermined end or pattern of development, as in plant growth – we don’t know exactly what a seedling will look like as an adult, but we can be sure of some parameters, because those are genetically determined by species. That pre-set developmental path is what makes plant growth a teleological process, while random motion, like spinning a roulette wheel or flipping a coin, is not. The most common teleological histories are religious in nature, moving from a fixed point of creation to a final culminating event that gives meaning to the whole thing (eg. Genesis to Revelations). Hegel wasn’t religious in a traditional Christian sense, but did believe in a personal notion of God as a highest, perfect, ultimate reality similar in some ways to the Platonic world of forms. This enabled him to propose a direction behind what appears to be a random flow of human events, but, as is typical of Idealists, nothing approaching “evidence” for these alternative spiritualities is ever offered. Fortunately, this is not a significant obstacle. Like “Hegelian Dialectic,” “The Hegelian Spirit of History” has an appeal to authority that can counter any pesky problems of accuracy.

Conca's muse is more fetching, but the Magic 8 Ball offers a better guide to events than a dialectical spirit of history. At least it recognizes its obvious limits.

The desire for transcendence, a superior timeless counterpart to our shifting human world, is a constant in human history. In religious terms, it is usually conflated with the afterlife, while in secular philosophy it appears as some sort of abstract, ideal super-existence. The danger in transcendence is that it imposes hierarchies where our actual lived experience is inherently inferior to some imagined other. At best, this provides a binding moral order to check human self-interest, but at worst, willingly sacrifices lives and even cultures to an impossible ideal. Because they exist beyond this world, transcendences are not falsifiable by empirical means, but assume their conclusions and retrofit any evidence to contrary. The religious tend to be honest and state openly that their belief is based in faith, but philosophers seem to want the reassuring structures of transcendence without submitting to the strictures of religion. The problem is that without faith, claims of transcendence require extraordinary proof, or they fail to rise beyond useless speculation. When someone like Marx actually imputes real value to Hegel’s phantasms, the results are cataclysmic.

Upper part of stele inscribed with the Law Code of Hammurabi, ca. 1760 BCE, diorite, approx. 2.1 m, Louvre

Control of the transcendent has always been the path

to power. Hammurabi's is one of the oldest legal codes known, and stele like this one were used to promote it publicly. The image at the top shows the king receiving his law from a god, which not only gives it a sacred authority beyond human objection, it establishes him as a direct link to divine will. His authority, like his law, transcends the human.

Of course, if this god is unreal, the system has a problem.

Of course, if this god is unreal, the system has a problem.

The careers of Hegel and Marx unfolded at a specific time in European

history, and, despite their claims of universality, are highly contextually

determined. The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution brought wholesale technological and social transformation, but the social criticism targeted the ideological and social

structures of the Ancien Régime. Given the close

links between monarchy and Church in early modern Europe, it was strategically necessary to undermine the supernatural basis of this authority.

Abolish the sacred altogether, and the entire Ancien Régime apparatus

disappears like smoke.

The crowning of Charles the Bald, flanked by Popes Gelasisus I. and Gregory I, Sacramentary of Charles the Bald, c. 869, BNF Latin 1141, fol. 2v

Metaphysically, the image of God crowning the Carolingian emperor directly is identical to Hammurabi receiving his law from the gods. But in the context of medieval Europe, the divine power is Christian. The notion that the monarch divinely supported was known as the Divine Right of Kings in the Middle Ages, and tied the power of throne and Church together in a precursor to the Deep State. Therefore, to overthrow the social order, both had to go.

Metaphysically, the image of God crowning the Carolingian emperor directly is identical to Hammurabi receiving his law from the gods. But in the context of medieval Europe, the divine power is Christian. The notion that the monarch divinely supported was known as the Divine Right of Kings in the Middle Ages, and tied the power of throne and Church together in a precursor to the Deep State. Therefore, to overthrow the social order, both had to go.

But that species-old desire for something bigger, something that gives purpose to the world, remains. Hegel’s

non-Christian teleology attempts to have it both ways, before collapsing under the illogic of the spirit of history. The problem becomes critical for Marxism, however, since, as a materialist philosophy, it allows for no sacred or transcendent dimension. Dialectical materialism, or the self-detonating marriage of a transcendental, Idealist teleology and a materialist history is not a “synthesis’ in any realm but the imagination. It is not sufficient to state that opposites coexist; it is necessary to explain how this can serve as the basis of a philosophical system once is becomes apparent that neither history, nor any other process or generation, creation, or evolution, conforms to this structure. The appeal, of course, is that is allows those of limited intelligence to assuage their resentment by believing impossible things, at least until the sociopaths actually attempt to implement it...

Big fun in the Peoples' Paradise, Cambodia style

Big fun in the Peoples' Paradise, Cambodia style

So to recap, Marx:

- believes opposites can be wished into coexistence despite all evidence to the contrary, because... Hegel

- fails to correctly characterize the historical development of the modern world

- fails to grasp experience-based learning

- fails to correctly identify the fault lines in society

- fails to acknowledge the biological realities of human social evolution

- proposes "solutions" that better suited to a different species on a distant world

- achieves statistically impressive 100% failure rate

And yet, no sooner does one dehumanizing Marxist dystopia collapse under the weight of collected atrocities, there is no shortage of mental deficients crying that next time will be different, and reality will finally conform to their wishes. Despite their professed materialism, these people exhibit a cultic belief in some sort of "True Marxism," separate from any historical manifestion or error. The system is empirically wrong to the point of not even

offering a useful metaphor for historical pattern recognition, but has endured

in ways that other historical errors, such as phlogiston and Piltdown Man, have

not. There must be more to this than another discredited philosophy.

M&M ad by Clemenger BBDO, Melbourne, Australia

A familiar pattern emerges. This isn’t philosophy, it is

faith, only one where “God” is a pallid fantasy of impossible secular

transcendence, and the acolytes capable of depravity unchecked by any external

moral code. Philosophically, the impossibility of a fusion of teleology and materialism is a terminal error, but it is no more an

obstacle to faith than problems dating the Flood in Genesis. “As Marx says” is

treated with scriptural reverence, rather than the more appropriate "so what" or “who

cares.” Marxism offers the satisfying

feeling of initiation into hidden wisdom by claiming to puncture a false

consciousness, and the moral superiority of a catechistic adherence to a

fictional equality of outcome utterly at odds with any natural process ever

observed. However, unlike religion, it asks nothing of its morally preening

zealots except violence and “revolution.”

There is an overt connection between Marxism and the early theorists of Postmodernism, though the latter would never openly refer to history as teleological. The term "Postmodernism" was actually coined by Jean-François Lyotard, a thinker who attempted to link social and technological changes to what is essentially a new conception of human nature. Although slightly predating the internet, Lyotard saw an increasingly electronic, connected, and media-filtered culture as transforming the individual human subject into a sort of decentered information packet potentially existing anywhere, but nowhere in particular. On a general level, this is not that different from Guy De Bord’s Society of the Spectacle or Jean Baudrillard’s notion of the simulacrum; both of which posit societal transformation from an authentic world of organic, hands on experience to a technologically mediated world of inauthentic interchangeable impressions. Insofar as they provide insight into the fabric of contemporary culture, these works are valuable, although many of their revelations had been anticipated by visual artists.

Warhol's genius was to predict the nature of celebrity in a mass media age. "Marilyn" is nothing more than a an image, replicated over and over until her moment passes and she fades into memory. His notion of "15 minutes of fame" seems especially prescient in an era of reality television and YouTube stars. The conception of identity as an empty, replicated image is fundamentally Postmodern.

The problem with Postmodern theory is that the contemporary cultural environment is presented as an inevitable transformation in basic human nature that seems almost metaphysical, rather than an artificial and rather fragile electronic web orchestrated by humans. And somehow all the theorists presume the same endpoint: the

dissolution of the human individuation, responsibility, and agency for a superficial

system of flickering signs with no connection to anything beyond themselves. The appeal of these "thinkers" despite the fact that what they describe isn't happening, suggests that we are drifting into the realm of wishful thinking and faith. If the development of communications technology is transforming

us into disembodied memes, why are basic human instincts like primate dominance

and in-grouping so prevalent on the internet? If a Postmodern state is

inevitable, how is the US economy adding tens of thousands of manufacturing

jobs per month? It’s a pretty feeble zeitgeist that can be exorcised with a tax

cut and trade policy. Could it be that the Postmodern world isn’t inevitable,

but the result of control of central nodes of key cultural institutions and

decades of terrible politics?

The idea that government and big business represent adversarial interests is a canard that is long past its sell-by date.

Although Lyotard included Marxism among the Modernist grand narratives rejected by Postmodernism, the two "systems" actually mirror each other structurally and are historically linked. Both dissolve the integrity and dignity of the human individual by subordinating it to some inexorable substructure (to use Marx's term) of existence, be that economic relations or technological mediation. Both are incoherent in treating an evolving system created and maintained by human effort as something that transcends human agency rather than proves it. Culture is a vast web of interlocking decisions, some free, some coerced, that exceeds the ability of an individual to fully grasp, but the unpredictability of countless interlacing butterfly effects is the opposite of the inevitability of transcendence. In fact, inevitabilities do not require fierce, orchestrated institutional pressure or fake news.

Steve Jobs' remarkable stream of innovations, and Apple's relatively scanty product development record since his passing suggests that the individual consciousness remains essential in an information age.

Beyond structural similarities, there are direct links between Postmodernism and the Marxist culture critiques that proliferated in the wake of the Frankfurt School. Postmodern theorists routinely describe the transformation of authentic experience into superficial sign systems in terms of commodification, or economic equivalency, which is exactly how Marx described the transformation of traditional labor in the factories of the Industrial Revolution. The idea is that converting something into a common measure of personal valuation robs it of "authenticity," a transformation so implausible that even countless evocations of The Philosopher's Name can't make it so. Evaluating something through an agreed-upon mechanism of exchange does not eliminate differences between things; if it did, there would be no desire to make an exchange in the first place. Likewise, the idea that a digital world is somehow undifferentiated requires almost willful blindness to the highly individuated behavior patterns in the on-line world. Even the vaunted Postmodern "cyborg", the transformative merger of human and technology is just a machine user.

Leonardo da Vinci, Design for a Flying Machine, c. 1488

Humans have used technological means to enhance their abilities since the first hominid picked up a stick.

The lure of an imaginary order beyond individual human existence is the age-old desire for transcendence. Whether God, the Forms, the Spirit of History, nineteenth-century economics, technological mediation, the one constant is the prioritization of some absolute above human self-determination, or even suffering. Where Marxism and Postmodernism profess to be different is in their rejection of higher meaning or values beyond material reality; their transcendences identify as secular. That secular transcendence is self-contradictory matters little when you can stand on the authority of a Marx or Baudrillard.

In all seriousness, the problem lies in Marx's uncritical adoption of Hegelian dialectic and teleology, while rejecting the quasi-religious idealism that they were based upon. At that point, the logic self-detonated, and the historical model became self-evidently wrong. When Postmodernism adopted a Marxist notion of inevitable historical progress towards some end state, it also imported a trace of Hegelian idealism that is diametrically opposed to its stated understanding of the nature of reality as atheistic and “scientifically” determined. Something can’t be inevitable and purely materialistic; either history is driven by a higher power that you can access and understand, or else there is no fixed endpoint. Postmodernity literally requires believing in contradictory things at the same time.

Exposing the delusional faith in secular transcendence that floats through history on the imaginary authority of “Hegel and Marx” is an example of applied deconstructive criticism. Deconstruction examines texts and other forms of discourse for internal contradictions but also offers a way to identify how impossible beliefs persist through time. Derrida proposed something called the Trace, an illusion of meaning that derives from past usage but was never actually possible, which fits the echo of Hegelian teleology and dialectic in the Marxist aspects of Postmodern theory like a glove. For Derrida, the Trace is the collective fantasy that allows us to act as if language means something outside of itself, which is itself an article of faith, though he hides it better than most. Yet one need not accept that all communication is fundamentally meaningless to see that Postmodernism as a historical concept certainly is; a house of mirrors atop a non-existent foundation that requires propagandistic deception and acts of faith to maintain. The question is not whether Postmodernity is inevitable, but why intelligent people would go to such lengths to promote dehumanizing, civilization-destroying falsehoods?